Less than 24 hours after Italy announced a COVID19 outbreak in Lombardia in Northern Italy, photos of barren Italian supermarket shelves were posted on Twitter. The subject of the social media buzz centered around one of Italy’s most favorite topics: pasta. Lonely bags of smooth penne pasta, penne lisce, remained perched on ravaged aisles. All of the penne rigate, ridged penne, was gone. While the president of Lombardia Attilio Fontana asked Italians to curb reckless shopping, assuring emergency precautions were in place, controversy over #pennelisce boiled over, becoming a trending topic on Twitter in Italy.

Continuo a guardare questa foto fatta prima al supermercato e penso al fatto che il grande sconfitto da questo virus sono le penne lisce che agli italiani fanno cagare pure quando sono presi dal panico e si preparano all’apocalisse. pic.twitter.com/Lq9Y06jdho

— ???????????????????????????????????????????????????? ????♂️ (@diodeglizilla) February 23, 2020

This Tweet by @diodeglizilla on 2/23 generated over 16K likes and over 3000 shares in a few days. “I keep looking at this photo I took earlier in the supermarket, and I think the biggest loser of this virus is penne lisce. Italians think it’s shit, even as they panic and prepare for the apocalypse.

@LaskaJuventus Tweeted “Pasta lisce is absolutely evil. More than the corona virus.

The controversy revolves around a longtime belief that smooth penne does not hold sauce like penne with grooves. Defenders of smooth penne say if the pasta is made well, it will absorb sauce and taste good even with just a few drizzles of olive oil. Italian chefs including Gennaro Esposito, famed Neapolitan chef, go as far to say that the ridged penne is inferior as it becomes overcooked on the outside.

While many shape origins of pasta are unknown, the original penne pasta was smooth. Meaning “pens” in English for its resemblance to the nib of an old fashioned quill, the machine to cut industrialized penne lisce was invented in 1865 by a pasta factory in Genoa. Giovanni Battista Capurro patented a machine to perform an inclined cut, considered a technological innovation. At the time, ziti pasta had popularized in Southern Italy and was dried in long tubes and then cut by hand, ‘maltagliati’ meaning ‘with mistakes.’ Popular Italian website Gambero Rosso speculates South Italians prefer lisce because of its birthright to ziti, which may explain why it’s most enjoyed there.

Penne Lisce, courtesy of Taste Atlas

Penne Lisce, courtesy of Taste Atlas

Maureen B. Fant, co-author of Sauces & Shapes: Pasta the Italian Way, has not seen penne lisce at her local supermarket in Rome in years, but she likes them better than rigate. She says, “All the original industrially made shapes were lisce until somebody figured out that striations would grab the sauce. Maybe the ridged penne holds a tad more sauce than smooth — though I have never been troubled by slippery sauce with penne lisce — but what you really want is not so much for the sauce to stick as to be absorbed into the pasta. This you achieve regardless of shape by choosing a pasta that has been extruded through bronze and dried slowly at low temperature. The barely perceptible rough surface of a good-quality pasta is much more important than the visible ridges.” Over an email exchange with her this week, we discussed whether American preference for ridged penne may have influenced Northern Italians. It may be embraced in cities like Milan because it is modern, a city that also loves sushi and international cuisine.

Near the border of Liguria in Tuscany, the Martelli family makes their ‘one of a kind’ penne, “Classiche”— smooth penne, a family business since 1926. They are proud to be the only pastificio in Italy that makes only penne lisce along with four other standards: spaghetti, spaghettini, fusilli and maccheroni.

Artisanal pasta is extruded through bronze dies, a soft metal that leaves a rougher surface for sauce to cling to. Teflon-drawn pasta is common in industrial pasta manufacturing. Exemplary grain quality and slow drying at low heat are the other two important factors that distinguish artisan from industrial. The ridges on industrial penne mask imperfections in the quality of the pasta ingredients by adding texture.

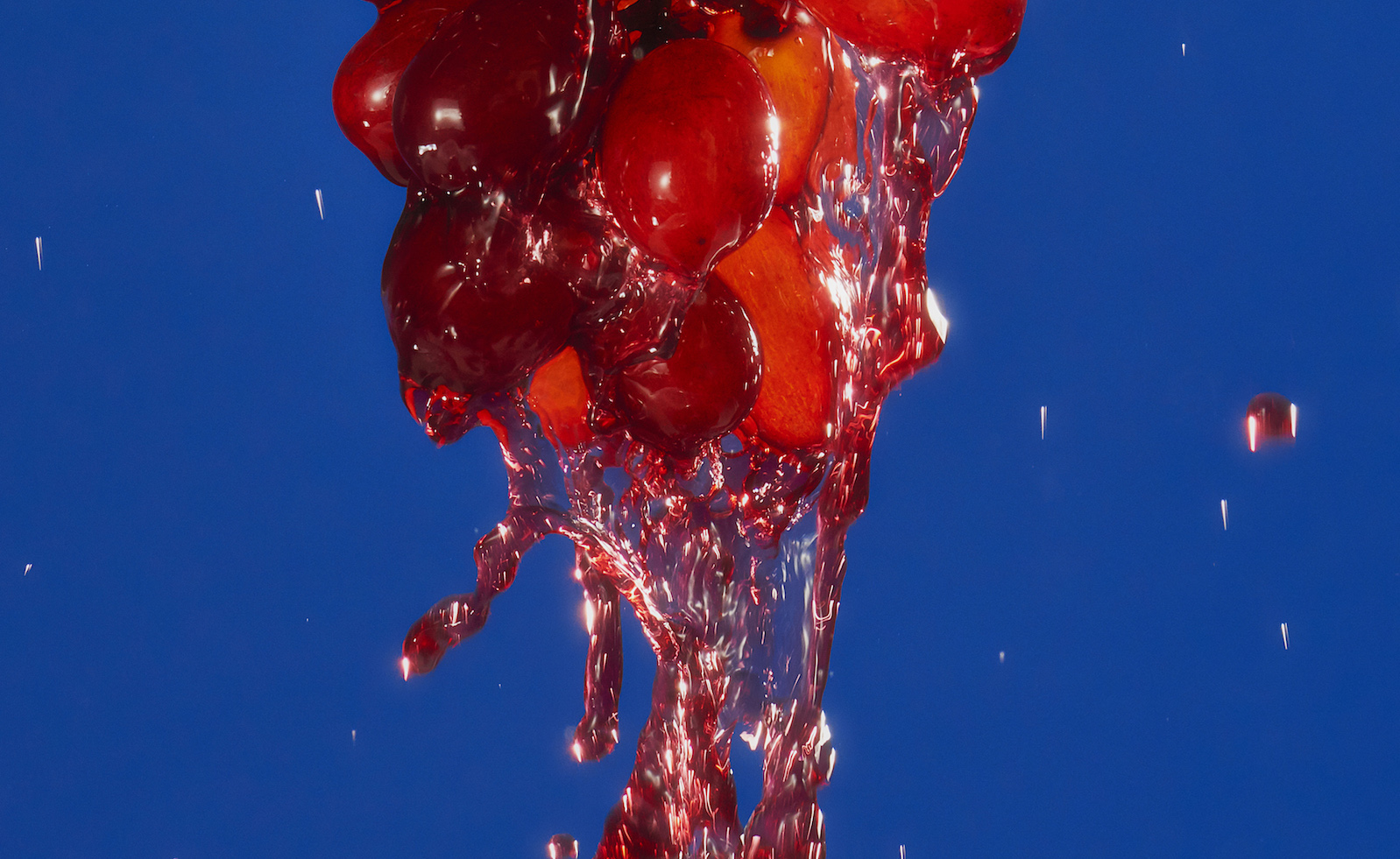

As an expat living in Milan, I’ve enjoyed penne arrabiata, the classic Roman dish made with penne, at friends’ homes and at restaurants when visiting Rome. Translated as ‘angry’ pasta, the tomato sauce is spicy, prepared with olive oil, garlic, and red chili peppers. Always served with penne rigate, I never gave it much notice. When the noise over penne surfaced on February 24th, I went to Eataly in Milan, curious to conduct my own taste test. Out of a few dozen artisanal brands, Mancini’s was the only penne lisce. Mancini grows their own durum wheat in Le Marche and has a cult following amongst chefs in Italy and abroad. Continuing my search, I went to the large supermarket by my house three times last week. In the pasta aisle, packed with over fifty kinds of pasta, no penne lisce was to be found, even from the industrial brands De Cecco and Barilla.

As soon as #pennelisce went viral, De Cecco took advantage of a marketing moment by defending it on social media (photo), reminding us they use bronze dies. A meme surfaced on Twitter of Marie Antoinette holding a book was replaced by a Barilla box of penne lisce, reading “if they don’t have anymore bread, they eat smooth penne.”

The discussion of Twitter went from feelings about penne immediately to how grocery stores are saving thousands of euros by learning about customer preference. At Barilla, globally, penne lisce is around 10% of the total penne production. It is sold primarily in the United States and Italy, mostly in Campania, in the South.

“Paccheri, a smooth shape, are now turning up in ridged versions. Still rare, but I’ve seen them in restaurants.” Despite what ridged pasta fanatics might think, Fant argues that the barely perceptible rough surface of a good-quality pasta—no matter where its eaten—is much more important than the visible ridges.