Confusion about food labeling would seem to be the ultimate #firstworldproblem. Isn’t our original skill as primates the ability to distinguish food from non-food? Ever since we emerged from the ocean, we’ve asked: Does it have prickly thorns or smells off? DON’T EAT. Does it have crunchy leaves or smells good barbecued? EAT. Our senses have been developed over millennia to protect our gut and nourish our cells, if only we’d listen to them.

But when it comes to food made by man, our ape skills are useless. Marketing lingo has gotten both very skillful and completely indecipherable. As a food writer, the top question I get from friends and readers is: “Should I believe product claim X, and will it guarantee me everlasting happiness?” (Short answer: no, and no).

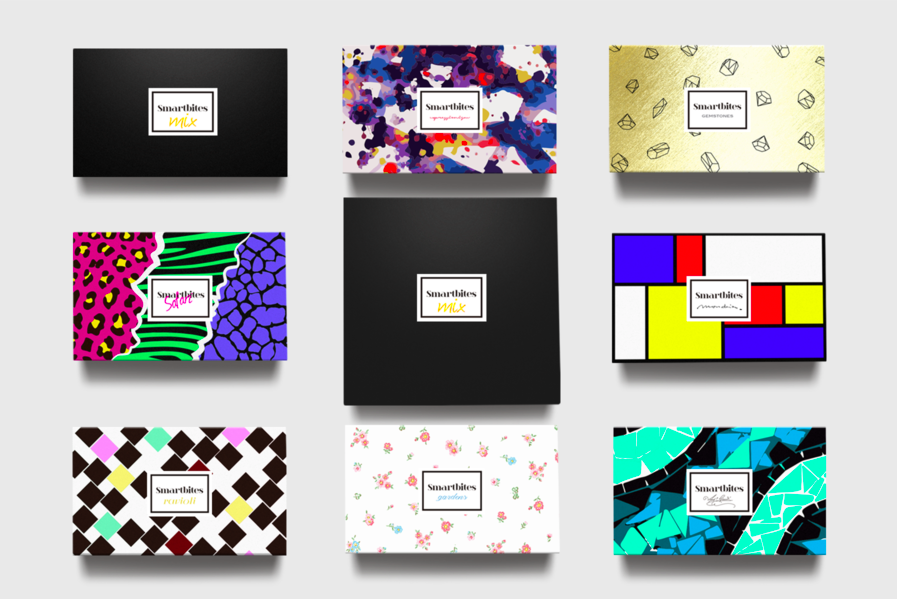

Enter the Noun Project. Led by Iconathon, a graphic design firm that produces logos for both commercial and popular use, Grace Communications Fund and Mother Jones magazine, this one-day event at the School of Visual Arts in New York City paired food activists with skilled icon-makers to create a new range of open-license logos to help explain where our food comes from.

The graphic fruits of their labor are pretty cute. Tom Philpott of Mother Jones (who offered food industry background at the event) calls them “emojis for foodies.” They offer a visual shorthand for the modern anxieties of industrialized food, including presence or absence of genetically modified ingredients, pesticides, and antibiotics. They also highlight some of the most exciting trends in modern food: “Grown on an Urban Farm,” “Locally Grown,” and “Aquaponics” are among these.

Promoting the efforts of small and sustainable farmers was a goal of the event: smaller operations producing great products usually can’t afford the marketing budgets of the multinational conglomerates. But I’m not sure if a crowdsourced logo can help them compete: since there’s no independent verification, the logos could simply be co-opted by those same big-budget marketing firms hired by the enemies of good food. Right now, there is only one logo with legal consequences for misuse: USDA Organic.

But most of the logos are thought-provoking and easy to understand. I can get behind anything that gets us to think more carefully about the food that comes in boxes and bags. Until I understand it all, I’m still using my ape mind and a pretty good nose.