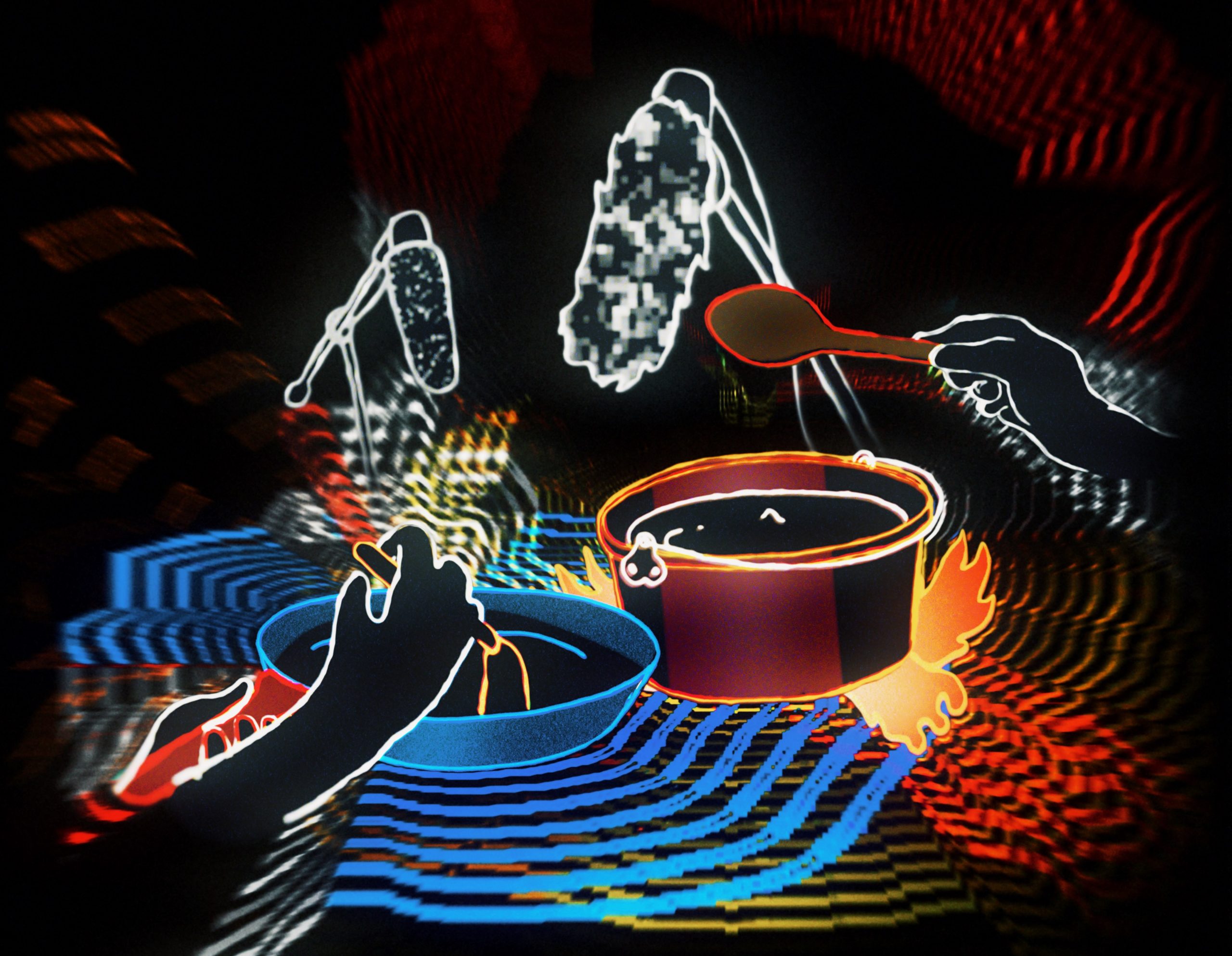

Gut Vision is a series about the ways that we not only consume food but also symbols.

David Velez is a sound artist, researcher and curator who works in-between Colombia and Huddersfield, UK on the acoustics of cooking. David pays very close attention to the sound of cooking. His performances, concerts and research are on the potency of food and sound as forms of resistance. The act of listening to ingredients, those who cook and the cooking process reveals a whole other world before us. David’s sonic studies give us glimpses of cuisines, makers and culinary practices that may be on the verge of loss and take us to places in-between immigrant kitchens in the UK to the infrasonic sound of the cosmos. In the below conversation with David, we discuss the complexities and paradoxes that emerge when we listen to food.

Somnath Bhatt:

Your practice is quite unique. Could you start by briefly explaining your process and what about sound led to your interest in the acoustics of cooking?

David Velez:

My process is intuitive and plastic. My work has become about lending my microphone. Silence to me is an active action because when I am silent, I am giving the voice to somebody else. I don’t want to work with a certain environment and reduce it to inspiration—I want to collaborate with the context and become its accomplice. I try not to replicate colonial-like models where the artists have a pre-determined and biased approach towards the hosting environment. For instance, for many years, colonialism reflected when anthropologists were forced to maintain a distance that eliminated the possibility of creating affectionate bonds with the hosting communities. I try to create a space of generosity and gratitude in which the participants and I converge and collaborate.

My interest in the sounds of cooking and food began four years ago. Initially I focused on textures, timbres and intensities of sound where the idea of “reduced listening” coined by the composer Pierre Schaeffer was a major reference. Reduced listening is the audible act of attending to the sound apart from its source. Reduced listening is about our capacity to connect sound with imagination. For example, you can be hearing the same sound as me, but because of our experiences, context and subjectivity, we are probably listening to different things. When we listen to the sound of frying, we will start to imagine the smell of food, its textures and so on. My very first community project with food was a workshop that I directed in Quindío, Colombia in 2013, where the participants recorded the sounds of the agricultural production of coffee because the sounds of coffee production links directly to their cultural identity .

SB:

What kind of complex paradoxes come up when listening to cooking recipes and the stories around its preparation? Why?

DV:

When I started working in immigrant kitchens and researching, the first paradox that I realized is that in England, they love the taste of immigrant food, but the actual presence of immigrants is not necessarily welcomed equally. Dishes like Tikka Masala, Jerk chicken and Kebabs are so popular in the UK. The food is appreciated, but there is strong condemnation of the smell of their cooking. Plenty of these negative reactions towards food scents got violent in the 50s and 60s. As recently as in 2019, a landlord named Fergus Wilson was banning people from Asia from living in his buildings because of the smell of their cooking.

Historically, the British empire got into India by means of trading spices, but there was a bigger agenda behind that—military, industrial and conquest. It is through food which I understood the political tensions between the UK and its former colonies. Britain claims to be a multicultural society, but most immigrants wouldn’t agree. Racism occurs also in terms of unconscious biases that are hard to detect but equally detrimental.

The colonial approach of Britain’s arrival to India, reflects today on aspects of cultural appropriation, when, for example, politicians tried (unsuccessfully) to give Protected Designation of origin to the British authorship of Tikka Masala.

These complexities behind food tell about the structures of power and privilege in society. It’s astonishing that these enormous large-scaled problems that involved thousands of years of warfare, can be traced from a hob in a tiny kitchen in Huddersfield.

SB:

In your current project Turmeric there is an interesting revelation of what takes place inside an immigrant’s kitchen—can you tell more about the adaptation that takes place when tropical foodways enter European kitchens?

DV:

Within my project Turmeric, Tikka Masala became a dish or a motif. The popularity of immigrant food puts on the table the contribution of diasporic communities in the UK.

I first moved to Huddersfield during a very harsh winter and the only joy to my seasonal affective disorder was spicy food. It was also interesting to think of the relationship that a colonial power has with its colonies in relation to spices. In Tikka Masala, the ingredients selection is interesting because turmeric was one of the spices that the British empire travelled to India to trade with. It’s a dish that gets a lot of love, it is one of the most popular dishes in the UK as it was voted on a poll in 2011. But at the same time, if you’re cooking it, you might still face backlash from neighbours and landlords because of its smell. This is something that has been happening since the 1950s when immigrants from Asia and the Caribbean finally had access to some of their ingredients which helped them to deal with uproot and homesickness. So, in 2018, I started to work with artists, musicians and cooks from Thailand, India, Taiwan and Colombia in the UK to document the sound that their recipes produce. Just like heat and scent, sound can also “emanate, propagate, communicate, vibrate, and agitate” to quote sound art researcher Brandon Labelle.

Cooking and food have technology built into it as well. Most of the spices that are used in Asian and Caribbean recipes were initially used to prevent bacteria. Instead of claiming the authorship of immigrant dishes, British society could just express solidarity and gratitude to the people who have been bringing all these flavours and poetic stories to their tables.

SB:

As someone who pays very close attention to the sound of cooking how do you find food and cooking can be a vehicle of resistance? How do food and sound act as something that builds global communities, resistance and solidarity?

DV:

There is nothing more quotidian, political and affectionate than cooking.

This quote comes to mind: “Food shapes culture and conflict shapes food. Resistance doesn’t only take the form of protests and marches—it’s in the food we share, the stories we tell, the gardens we grow (…)”

Politics is permeated through food and the making of it. The immediate possibility of food, gives anyone the ability to be self-sufficient. My experience of working with artist, cook and horticulturist Elena Villamil in Colombia is that food gives the possibility of being independent and autonomous – these political powers do not depend on a system that is corrupt. I will speak more about my collaboration with Elena later.

Ideas of ‘alterity’ can also be implied through this notion of openness and receptiveness. When we eat, we are sort of closed into our basic diet. When we eat somebody else’s food, we are not only the food getting, but the history behind ingredients and the biological technology.

Trying new foods and listening with generosity are helpful to get rid of our biases. Even when we listen, we have plenty of biases. Research shows that in certain working environments if you have a foreign accent, or if your accent hints you are from a less privileged neighbourhood, or if you’re a woman, your treatment will differ. There’s a lot of biases that happen with sound. How do we get rid of some of these biases and how can sound let them explain them to me? These are questions that I want to address in my work.

SB:

A lot of your performances and recordings connect the past with the present. From the act of recording the vanishing sound of a lost recipe, indigenous ingredients no longer in the market or a banned drink, what makes you compelled to work with these notions?

DB:

There’s a universe of sounds and tastes that are telling us truths that we are not aware of. In my work, I want to bring what’s in the background to the foreground. Food is a major industry and it involves so many political agendas and power structures. As an artist I’m interested in how food recipes contain critical stories of hegemony and privilege, but simultaneously, every dish spreads the lively vectors of life across the universe. Food nourishes your body by becoming part of it. It is really poetic and beautiful to consider that you have something that has gathered together so many geographic contexts on your table.

One of my first political approaches to food was the concert Se lo comieron todo / They ate it all where I worked with Cristián Castro, a Chilean chef who lives between Italy and the coastal city of Valparaiso. He created a menu that was a critique of neoliberalism. The recipe he cooked, was based on Vidriola, a kind of fish native to Valparaíso, that is no longer found on the coasts because of the detrimental environmental policies of this economic model. This recipe and the concert became a story about how neoliberalism neglects fishermen and townsfolk in Valparaiso from seafood. The ocean is almost empty in Valparaiso. It is another paradox because that fish now has to be imported. For this concert, Christián bought the rest of the ingredients in a major supermarket chain that belongs to a millionaire tycoon in Chilé as a gesture of irony.

Another important piece connecting my work with culinary sounds and the politics of food was Ecos de la chicha. Chicha is a very popular indigenous maize drink in Colombia. In the early 1900s, beer companies realized that Chicha was competing with their sales. These breweries lobbied and banned this beautiful drink which denied people of their cultural heritage. Paradoxically, in their origins, the breweries that banned Chicha, hired locals to work in the factories founding a neighborhood called La Perseverancia which is popular for its relation to Chicha production and tasting.

My collaborator in this piece, Elena Villamil, is a self-taught artist, cook and horticulturist who has a space near La Perseverancia where she grows all of her food. The concert was performed in her garden which is surrounded by tall corporate buildings, and where she resists gentrification with her teaching, art and food. Ecos de la Chicha featured a group of 10 cooks which some took part of a workshop in which we all learned to make chicha with Elena. In the workshop we recorded the sound of its preparation as an acoustic recipe. In the performance, the sounds were soothing and vibrating and they ended up having an uplifting and profound effect on the collaborators and the audience. I performed with sine tones which are the most basic forms of sound in musical synthesis. These sounds present a beautiful contrast with the organic and intricate sound of cooking. To me, cooking sounds are ritual sounds that celebrate the importance of the ceremonial in contemporary everyday life. These sounds resonate in the background and are deeply traced in our memory. They refer to luscious experiences where food connects the body with the energy of the sun as the ordinary and the extraordinary converge in every meal.

Just like heat and scent, sound can also “emanate, propagate, communicate, vibrate, and agitate”

SB:

How did market shouting become an area of deep interest to you? What is the future of sounds like these with the advent of retail giants like Amazon who deliver food and produce right to our doorstep. I worry they will never be heard anymore.

DV:

The idea was conceived in the Ballaro marketplace in Palermo, Sicily which has always been a city of immigrants. Sicily connects different parts of Europe with Africa and the world. Public food markets, like Ballaro, are places where we can experience multiculturality and the beauty of ingredients, foods, sounds and cultures. You understand the culture of a place, town or a city by listening to their food markets.

In 2019 I created a concert in a market in Huddersfield, where recordings of market shouters were in dialogue with the actual shouting traders, as a back and forth. Market shouting is really competitive; they are really proud of how loud they can get. The sounds I played were gathered from other markets in India, Poland, Taiwan, UK, Chile and beyond. The whole world became invisibly present and heard in this marketplace.

Sadly, market shouting is considered acoustically polluting and unsanitary in today’s global health crisis. Tony, one of the market traders that I worked with, told me about shouting, “This is a dying art, but as long as I live, I will keep this going.” When market shouting is banned and vanishes, you are taking one of the most artistic aspects of someone’s life away. Yes, they are shouting to sell food but the way they pronounce words and the clever poetry that happens every time the prices change—they have promotions on the fly—is the art of ordinary life.

SB:

Any future projects you would like to share – I know you are working on something with the beetroot and its connection to the cosmos?

DV:

I am working on a multi sensorial installation called Un último día perfecto. It is about beetroot and its incredible technological and poetic possibilities —remolacha in spanish. Research from the scientist Li-June Ming, shows how beetroot could help prevent Alzheimers and other forms of dementia because it enhances blood flow to the brain. A chemical scientist and a pianist Jeanne McHale studies the leaves of beetroot and how they work as efficient receptors of solar energy turning it into chemical energy. Beetroot also stores chemical energy really well. There’s so much more about the beetroot other than just the taste and the pretty color. Carl Sagan, in his book Cosmos, speaks about “the last perfect day,” the day before the sun starts to die. I am interested in connecting the idea of “the last perfect day” as a solidary gesture with somebody with Alzheimers when the irreversible effects of dementia start to set in. Also with the energetic crisis and its devastating effect on the environment, there will also be one last perfect day.

The idea is to create an installation that connects many concepts around one food ingredient and its special connection with the cosmogonic. The sound of the sun produces a frequency that is inaudible to the human ear but which connects with our body by the means of vibration and touch. We will be using a special speaker that allows the spectators to sense the vibration of the sun in the installation. There’s an interesting story about the sun and sound, in which those suffering from hearing impairment believe that the sun makes a sound, but when they have surgery and recover, they experience disappointment of not being able to hear it. Sounds need a medium to propagate and this is another reason why we cannot experience the loud infra sounds of the sun on the earth. In the installation, we will project the vedic frequency of the sun which has special meditative effects, and we will feature a billboard-sized screen with a sun which is used in parts of China as a substitute when smog pollution makes the sun invisible. In the middle of the installation, we’re going to have a small allotment where we’ll be growing beetroot under artificial violet light which also induces meditative states. Visitors will be able to speak to the beetroot through transduction, which turns the vibration of sound into electrical stimulation. Beetroot juice will also be served as part of a ritualistic experience. We are trying to push all the possibilities of this food—Infrasonic, spiritual, ecological and medicinal, economic, energetic. It’s connecting the beetroot with the sun and the entire cosmos.