What follows are the tendrils of a project I am calling Seeding Planthroposcenes. Taking the utterly absurd form of a step-by-step guide to getting out of the Anthropocene, this project picks up recent calls for inventive forms of speculative fabulation. This form does well to channel both my rage about our current predicament, and my playful and loving — if also serious — aspirations for dreaming worlds otherwise.

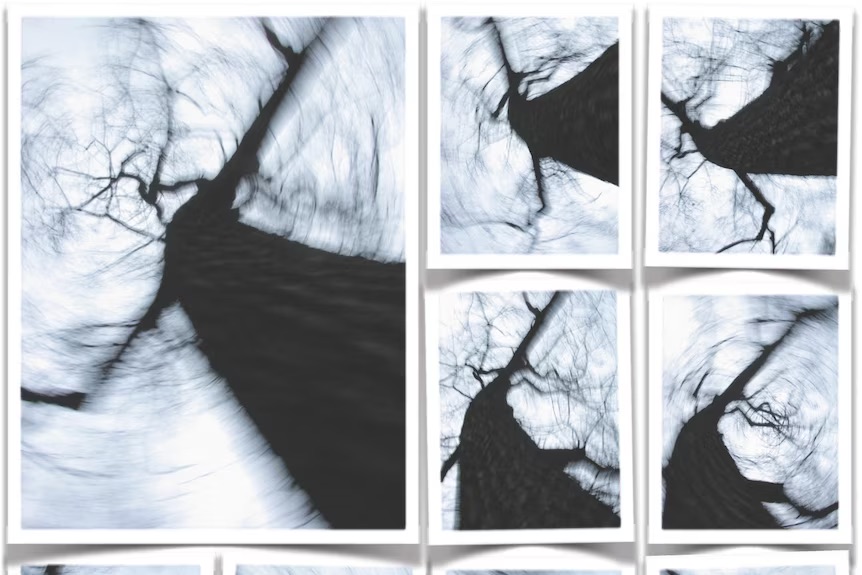

This is not so much an essay as it is an incantation. We must remember that we are living under a spell, and this spell is destroying our worlds. It’s time to cast another spell, to call other worlds into being, to conjure other worlds within this world. The situation we find ourselves in now leaves us at the limits of language and grasping at the edges of imagination. We need art, experiment, and radical disruption to learn other ways to see, feel and know.

Consider this as an invitation to experiment with ways of imagining a different kind of “we” for catalyzing action in the world.

Step 1 | Never forget this: “we” are not “one”

Say it again. And again. We cannot forget to keep asking: Precisely who is hailed by this Anthropos, that figure positioned at the helm of the Anthropocene? Anthropocenic rhetoric calls out “Man” as the agent of his own demise and simultaneously vaults him into position as the only viable saviour of the planet: “We got ourselves into this mess. Only humans can get us out.”

Even as Anthropocenic thinking attempts to call our attention to — and finally hold us responsible for — the egregious effects of our actions, it still figures humans as a singular agent, transcendent over and separate from some Edenic nature in peril. These narratives re-centre rather than de-centre “Man” as the agent with natural dominion over this planet’s future.

Do not get distracted by the misplaced concreteness of scientific efforts to articulate the physical markers and temporal boundaries of a geological era made by humans. What we are witnessing is the apotheosis of five hundred years of colonial violence, extractive capitalism, white supremacy, misogyny, and the hubris of human exceptionalism.1 The Capitalocene and the Plantationocene are apt monikers to identify the forces that have long been at work terraforming the planet.2 These destructive forces are propelled, not by all people, but by those particularly egregious ways of doing life modelled on self-aggrandizing Man.

Remember this: not all are hailed by this figure or form of life. Capitalism and colonialism are not to be mistaken as natural or innate to human existence. They are not inevitable consequences of human evolution or civilisation. But they have catalyzed and conditioned our current predicament: a world rife with anti-Blackness and other racisms, expanding forms of extraction and enslavement, climate emergencies and ecological ruin.Marisol de la Cadena calls our attention to those Anthropo-not-seen, those whose lives and lands continue to be spent in the accumulation of wealth by colonial and neocolonial powers.3 These are the people who remain targets of dispossession and enslavement even — perhaps especially — today as capitalism gets into high gear in its efforts to “go green” and “save the world.” Don’t believe the hype of sustainability rhetoric.4 The worlds built by colonialism and racial capitalism are unliveable for us all.

Step 2 | Break this world to make other worlds possible

There is no way to “mitigate” Anthropocenic violence using Anthropocene logics. Refuse calls to design for the Anthropocene.5 Such designs are precisely what Erik Swyngedouw identifies as the “technological fixes” that will keep us locked into the same rhythms of extraction and dispossession.6 Refuse to be lured into those climate change edutainment complexes, like Singapore’s Gardens By the Bay, whose gleaming glass, metal and concrete infrastructure and capital- and labour-intensive design exquisitely exposes the ruse of sustainability as an aesthetic manoeuvre grounded in Edenic visions of nature.7 That is not the kind of green that will save us.

- 5. https://www.academia.edu/38607269/From_Edenic_Apocalypse_to_Gardens_Against_Eden_Plants_and_People_in_and_After_the_Anthropocene

- 6. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0263276409358728

- 7. https://www.academia.edu/12783355/Edenic_Apocalypse_A_Photo-essay_of_Singapores_End-of-Time_Botanical_Tourism

Yes, there are apocalypses already ongoing all around us. The decimation of the Boreal forest and all its relations to extract bitumen on stolen Indigenous land in Canada is one such apocalypse. But giving in to apocalyptic thinking is itself a kind of exit strategy, an easy out. Ruin porn, including those all-too compelling images of plants rupturing through abandoned buildings in Detroit and Chernobyl, thrives on this narrative of “a world without us.”8 The earth will be better off without people, so we are told. Beware of such apocalyptic thinking.9 Anthropocenic thought catches us up in thrall of apocalypse and sets us to work, furtively dreaming the end of times.

We must refuse what Donna Haraway calls the “tragic detumescence” of a narrative arc that is bent on pulling the entire planet toward unstoppable catastrophe.10 Do not resign yourself into thinking that this is how it has to go down; as if apocalypse is precisely what will have been.11

Resist the lure of apocalypse like your life depends on it. Frederic Jameson reminds us that it’s easier to dream the end of the world than the end of capitalism.12 And so, to thwart the momentum of Anthropocene worlding we must serious effort into dreaming the end of capitalism and activating processes of decolonization. And while it is clearly time to dismantle these Anthropocene infrastructures, there is no need to wait until the end of this world to begin to conjure liveable ones.13

As Stuart McLean reminds us, there are as yet other worlds in this world.14 And there are, as yet, worlds to come. But which worlds will be liveable? Aimi Hamraie asks us to question the neoliberalism and ableism of the concept of livability: livable for who?15 It’s time to rethink the very constitution of this “we” if we want to learn how to make worlds livable for all.

Step 3 | Repeat this mantra: “We are not alone. We are not alone. We are not alone …”

Looking back at the past five hundred years of efforts to assert Western Man’s independence from — and power over — nature, it is clear that we should never be trusted to act alone. Anthropocene thinking is so obsessed with Man’s independence, with unilateral action and autonomy, that it forgets that there are other forces and powers among us, including those with significantly better skills in the realm of world-making and planetary-scale change. In some cases, these beings have billions of years more experience than us in terraforming liveable worlds.

Step 4 | Name our most powerful ally

Who made this planet liveable and breathable for animals like us? Say it out loud: the photosynthetic ones. Photosynthetic organisms form a biogeochemical force of a magnitude that Lynn Margulis assures us we have not yet properly grasped.16 More than two billion years ago, photosynthetic microbes spurred the event known today as the oxygen catastrophe, or the great oxidation. These creatures dramatically altered the composition of the atmosphere, choking out the ancient anaerobic ones with poisonous oxygen vapours. If we were to continue to fall into the trap of naming linear, time-bound eras after singular agents, we might be rattled to think that we are living in the wake of what should have been called the “Phytocene.”17

Photosynthesisers, like cyanobacteria, algae, terrestrial plants and trees, are the planet’s most powerful agents of elemental rearrangement.18 Duygu Kaşdoğan shows us that the science of photosynthesis, with its calculative metrics bent on extracting value from green beings, is mired in the logic of naturalised capital.19 These green beings must be understood otherwise; that is, as practitioners of a kind of alchemical, cosmic mattering. We think plants can’t move, but they reach out across the cosmos, drawing the energy of the sun into their tissues so that they can work their terrestrial magic.20 Pulling matter out of thin air, plants must be understood as world-making conjurers. They teach us the most nuanced lessons about matter and mattering.

More powerful than any industrial plant, vast communities of photosynthetic creatures rearrange the elements on a planetary scale.21 They know how to compose liveable, breathable, nourishing worlds on land and in the water. As they exhale, they compose the atmosphere; as they decompose, they matter the compost and feed the soil and the oceans. Holding the earth down and the sky up, they sing in nearly audible ultrasonic frequencies as they transpire, moving massive volumes of water from the depths of the earth up to the highest clouds. They cleanse the waters and heal the land, while nourishing all other forms of life. And for those caught up in the thrall of an economy that fetishizes carbon, perhaps the most important art these creatures practice is sucking up, with gusto, the gaseous carbon emissions we humans generate so abundantly.

To say that forests and marine microbes form the “lungs of the earth” is an understatement. They literally breathe us into being. All cultures turn around plants’ metabolic rhythms. Plants are the substance, substrate, scaffolding, symbol, sign, and sustenance of political economies the world over. We must learn how to work with and for the plants so that we can be nourished and clothed and sheltered and pleasured and healed — without destroying the earth.

Plants are the world-makers we need to heed if we hope to grow liveable worlds. And our worlds will only be liveable worlds when people learn how to conspire with the plants.

Step 5 | Seed Conspiracies with Plants Everywhere

Repeat this again and again: We are of the plants. Now, if this is true, then the figure that should ground our actions is not the self-aggrandizing Anthropos so much as a strangely hybrid figure we could call the Planthropos. And now try wrapping your mouth around this word until it rolls off your tongue with ease: Planthroposcene. (Yes, it’s awkward and you will sound silly. But just give it a try.) A Planthroposcene is aspirational episteme, not a timebound era, one that invites us to stage new scenes and new ways to see and seed plant/people relations in the here and now, not some distant future. And it is grounded in the wisdom of the ancient and ongoing radical solidarity projects that plants have already cultivated with their many people.

Rather than circumscribing the terrors we face now, Planthroposcenes invite us to root ourselves into a way of doing life that would break the frame of Anthropocene logic. Planthroposcenes point to the joint and uncertain futures of plants and peoples and demand we change the terms of encounter so that we can become allies to these green beings.

Anthropologist Tim Choy makes a powerful call for the formation of a conspiracy of breathers.23 His is an aspirational politics in which people learn how to con-spire, that is, to breathe together, in order to fight against the atmospheric effects of industrial exuberance.24 Choy helps us to think conspiracy otherwise, not as a sinister association, but as a form of solidarity for a liveable politics. It is time to extend his call for a conspiracy of breathers to include the plants. That is, we need to learn not just how to collaborate, but also how to conspire with the plants, to breathe with them.

Remember this: what is good for plants is good for everyone else, human and nonhuman. Get on their side. Consider yourself at their service. Get to know plants intimately and on their terms. And be sure to tap into their desires for forms of life that are not for us. Support their efforts to keep the earth cool and the waters cleansed. As Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reminds us, give plants and their soils space and time to flourish outside of the rhythms of capitalist extraction and the chemical violence of industrial agriculture.25 Remember: they need their pollinators; they need their fungal relations; they need their animal allies.

Above all, plants need humans to radically reconfigure how we stage our relations with them. Indeed, if plants are sun worshipers, perhaps we ought to be plant worshipers. A little reverence for the plants could go a long way. Invent rituals. Start a local church for plant worship. Don’t worry, reverence for plants doesn’t mean you can’t eat them. But it does mean it would be polite to thank them for their generosity. Just think: if you had to consult the plants to ask permission to use them, industrial agriculture, strip mining, clear-cutting and the expanding concrete of urban sprawl would be inconceivable. Just ask, they will tell you.

Step 6 | Uproot colonial common sense

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang affirm that decolonization means giving stolen lands back to Indigenous peoples.26 Tiffany Lethabo King, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Katherine McKittrick teach us how to reckon with and dismantle the overt and covert ways that settler states are structured on white supremacy, anti-Blackness, slavery, and the erasures of existing Land/body relations.27 Perhaps one step towards decolonization demands we disrupt the all-too colonial common sense that shapes how we apprehend – that is, both how we see and how we seize – both land and plants.

Does talking to plants sound crazy to you? Consider this: just a handful of generations before you were born, your ancestors’ lives were intimately entangled with plants; they knew how to cultivate and forage plants for nourishment, medicine, art, craft, and shelter. For millennia, people have been attentive to plants’ powers and predilections, especially those whose lives and livelihoods get them tangled up with the plants and caught in their spiralling whorl. There are gardeners, farmers, hunters, healers, herbalists, cooks, artists, naturalists, foresters, scientists, and shamans all over the world who consider plants as sentient beings worthy of address. Lots of people hear plants sing, though not necessarily in the audible registers you might anticipate.

And at the same time, many people — perhaps even you — would think this is absurd. Sure, you read that story about plants in your Facebook feed: “Science has confirmed that plant roots have a kind of swarm intelligence …”28 But we don’t need the disenchanting sciences of plant sensing to tell us what plant people have long known.29 What we do need to do is make strange the disenchantment and scepticism we have inherited from those whose power was secured in part through policies and sciences designed to invalidate all other ways of knowing the world. It was the colonizers, of course, who refused to believe local and Indigenous people’s claims that the plants can sing.

We have to remember that human exceptionalism is another colonial formation, one that violently evacuates the liveliness and sentience of the more-than-human world around us. And so, it’s time to detune this colonial sensorium which has such a hold on our perceptions and actions in the world.30

To do this, we need to upend everything we believe is common sense. Forget everything you thought you knew about the living world, especially what you believe is perceptible, imaginable, reasonable, legible, and meaningful. Refuse the disenchantments of a mechanistic science that renders more-than-human lives as alienable bits of life and death ready to be portioned off as property, resource, or commodity.31 Sideline colonial and capitalist moral economies that dictate what is good, valuable and true — especially those that naturalise economic growth and extraction as the work that is proper to “Man”.

Refuse to discipline or deride local and Indigenous cosmologies. Push back on every contortion or erasure or reduction of their knowledge that seeks to make such practices legible or commensurable or rational to science. Do not appropriate Indigenous knowledges but do the work to make yourself receptive and responsive so that you can take these knowledges seriously. Planthroposcenes make space for other ways of knowing and storying the living world. Remember: there are people all over the world who have the protocols, the know-how and the responsibility to consult the plants.32 Liveable worlds need people who know how to talk to the plants.

Step 7 | Vegetalize your sensorium

Once you’ve started to unsettle the colonial common sense that pervades your perceptions and attentions, it is time to vegetalize your sensorium so that you, too, can learn with and alongside the plants.33 As a co-conspirator supporting their world-making projects, you will need to apprentice with them. What do plants want? What do plants know? What can a plant do? We do not yet know. But you could reach toward them with the openness of not knowing and forget what you thought counts as knowledge.

Consider this: your sensorium, especially your senses of colour, texture, taste, touch, and smell, is already articulated by plant life. Their forms inspire your aesthetics, entrain your habitus and excite your imagination. From this perspective, your senses have already been vegetalized. And yet there is still much work do to learn how to extend your synesthetic sensorium to meet their lively worlds.

To awaken the latent plant in you, you will need to get interested in the things that plants care about. Though plants don’t have eyes, ears, noses or mouths, don’t be fooled — they can sense in ways that allow them to see, hear, smell, taste, feel and respond to the world.36 Let their planty sensitivities inflect your own. Tune in to the different ways they do time; learn to follow their tempos, temporalities, and rhythms. Pay attention to the ways they defy all-too-human notions of individuality, bodily integrity, subjectivity, and agency. Let the plants redefine what you mean by the terms “sensing,” “sensitivity,” and “sentience,” and by what you understand as a community and a relation. Let yourself be lured by their tropic turns, and you will soon acquire freshly vegetalized sensory dexterities.

You can also cultivate your inner plant through incantations, hypnosis, meditation or yoga.37 Vegetalization is possible because your body does not end at the skin. Your contours are not constrained by physical appearance. Your morphological imaginary is fluid and changeable. Indeed, your tissues can absorb all kinds of fantasies. Your imagination generates more than mere mental images; its reach extends through your entire sensorium. Simultaneously visual and kinaesthetic, imaginings carry an affective charge. They can excite your muscles, tissues, and fascia, heighten, or alter your senses. You can fold semiosis into sensation. Perceptual experiments can rearticulate your sensorium. And by imagining otherwise, and telling different stories, you can open up to new sensible worlds.

You could also let the plants work directly on you. Cannabis and Ayahuasca have been great allies for those seeking to palpate the sentience of the more-than-human world.38 But above all, involve yourself with plant life.39 Make space for plants to take root and take the time to watch them grow. Linger among them and let their sentiences and sensibilities alter your perception, how you think, how and what you know.

Step 8 | Take ecology off the grid

As you set to work disrupting colonial common sense and vegetalizing your sensorium, the world will start to look and feel a lot different. You may begin to sense things you have never perceived before. You may get the feeling that you are being watched everywhere you go. Indeed, the plants and trees are not indifferent to you: they are paying very close attention to all the beings that ingather around them. They know how to lure you and their other co-conspirators with force.

Start with the plants, follow their inquisitive growth, their running roots and rhizomes, the widespread movements of their pollen and seeds, and an entire ecology of beings, becomings, and processes of coming undone will soon become perceptible. Get caught up in the involutionary momentum that propels these beings into one another’s lives and you will soon start to perceive affective ecologies taking shape among the thicket of relations all around you.40

Cultivate modes of attention that allow you to perceive what matters to the plants and their co-conspirators. Becoming sensor, tune into this ecology of practices and practitioners. Follow the push and pull, the attractions and repulsions, the happenings taking shape in and around the plants. Get a feel for the ways that plants practice their arts at the cusp of life and death. With time you will begin to unsettle your colonized sensorium, and new worlds will open into view.

Develop protocols for an ungrid-able ecology — a mode of inquiry that refuses the colonialism, militarism, heteronormativity and economisation of life that grounds conventional ecology.41 Resist desires for legibility and statistical generalisability. Refuse attempts to calculate an ecology’s energetic efficiencies or apply cost-benefit analyses. Invalidate metrics that would parse ecological relations into mechanical parts. Break all automatic, prefabricated sensors.

Over time you will begin to forget what you used to think “nature” was; you will forget how you used to think life “worked”; and eventually you will forget, too, the naturalising tropes that made you believe that living beings “work” like machines, or that forests perform “ecosystems services,” or that “reproduction” and “fitness” were the only valuable and recordable measures of a life.

Call out the colonial and capitalist desires of the ecological sciences. Say no to conventional ecology’s exacting metrics that justify an extractive ecology indebted to expansion and dispossession. Beware of Anthropocene ecologies that reduce land-care practices to resource management. Do ecology otherwise.

Decolonizing ecology in settler states like Canada, the US, and Australia means restoring Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship to stolen lands and making land-based reparations to Black communities living in the wake of slavery.42 In any Planthroposcene, colonial governments must cede control over land management and make space for dispossessed communities to bring ceremony and healing to their lands and bodies.

The fires raging out of control across settler states, are a direct result of the removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands and the genocidal suppression of their knowledge and practices, especially the art and ceremony of tending lands with fire. Indigenous knowledge keepers know how to conspire with fire to grow liveable and nourishing worlds.43 On Turtle Island, oak savannahs around California, British Columbia, and the Great Lakes, were made over millennia by Indigenous people bringing fire to shape relations across lands, creating abundant worlds for ceremony, foraging, gardening, and hunting. Restoring Indigenous leadership to land stewardship is a form of harm reduction and climate action.44 These are the plant-people conspiracies that will save us.

- 43. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285728799_Maintaining_the_Mosaic_The_role_of_indigenous_burning_in_land_management

- 44. https://indigenouslandstewardshipto.wordpress.com/ceremony-and-actions/ilsc-calls-for-a-complete-ban-on-pesticide-use-in-high-park-indigenous-stewardship-is-climate-action-and-harm-reduction/

Step 9 | Garden against Eden

Forget everything you thought a garden was. And everything you thought a gardener was supposed to do.44 Your job is to stage scenes of plant/people conspiracy to keep this planet liveable and breathable. Your primary commitment will be to support plant growth. Everywhere. Start by letting the plants grow where they want to: let them break through the concrete; root into every fissure and surface; grow through the holes in every fence.

Don’t be afraid of the plants. Remember, those plants we vilify as “invasive species” are here to teach us about the ravages of colonialism.45 The plants themselves are not evil. They grow where lands have been destroyed. They grow in sites of dispossession. They grow where lands and bodies are out of relation. Before we poison the earth with pesticides to eradicate non-native plants, or rip them out with relish and fury, we need to ask ourselves what they are they up to?46 What are they teaching us about colonisation and the ruins of capitalism?47 How can we conspire with them to heal lands and bodies?

- 45. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1068/d13006p

- 46. https://indigenouslandstewardshipto.wordpress.com/ceremony-and-actions/ilsc-calls-for-a-complete-ban-on-pesticide-use-in-high-park-indigenous-stewardship-is-climate-action-and-harm-reduction/

- 47. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/earth-day-indigenous-scientists-academics-and-community-members-take-the-lead-in-environmental-causes-1.4605336/every-plant-and-animal-is-useful-to-us-indigenous-professor-re-thinking-how-we-deal-with-invasive-species-1.4605344

Planthroposcenes uproot the infrastructures of our Anthropocenic cities, which are founded on Edenic desires of a nature tamed and contained by Man.48 Give those old-order infrastructures back to the plants and the fungi; let them decompose. Wild urban plant growth certainly does portend the decline of Empire, but in a Planthroposcene, wild growth will not be read as a sign of ruin.

Planthroposcenic cities will be designed to support plant life everywhere. Each surface will offer an affordance, a place for plants to root and grow and decompose. Perhaps one day you will conspire with the plants to grow your own home. Perhaps cities will grow themselves into cooling forests, brimming with nourishment.

Planthroposcenes thwart the capitalist imperative to grow markets, supplanting the drive for capital with the imperative to give plants the time and space they need to freely articulate relations with their allies and express their fullest desires. Humans will have to cede their biopolitical powers over lands and bodies. We will finally come to the realization that we are not the ones in control.

Step 10 | Make art for the Planthroposcene

Refuse the aesthetics of ruin porn, which constrains our imaginations about wild growth to sites of cultural decay, as if it is only in the wake of human extinction that plants will be able to express their full, unfettered (read: monstrous) powers.49 Cultivate, instead, a taste for Planthroposcene porn: art that keeps people in the game by staging intimate relations between plants and people; art that figures “nature as lover”; art that lures us into the realm of more-than-human pleasures.50 Curate your own EcoSexual Bathhouse and make love with the plants.51 Join Slovenian artist Špela Petrič and the Plant Sex Consultancy to design vibrators for lonely potted plants and flowers that have lost their pollinators.52

You too can learn how to photosynthesise. Activate your own capacity for cosmic mattering by learning Chimera Rosa’s protocols to tattoo your skin with chlorophyll.53 Join artists from Dance for Plants to create performances for the potted plants that are slow dancing on the window ledges of your apartment.54 Apprentice with Mexican artist Gilberto Esparza to design lively nomadic plant support systems.55 Build the bodies of your planimal-machines from electronic waste harvested from the ruins of capitalism and engineer them to draw their energy from bacterial life, so that when they suck up raw sewage downstream from the toxic industrial flows all around you, they can transform it into water for the plants and their allies.

Whatever you do, conspire with the plants to make art like your life depends on disrupting the colonial common sense that would leave us all to die in the Anthropocene.

***

Natasha Myers is Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at York University, Toronto. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram. An earlier version of this article appeared in 2018 in The World to Come: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene, published by the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida.