This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Pre-Order your copy here.

Editor’s Note: This piece was commissioned, written and delivered in April 2022. We are printing the piece in its original format, with permission from both FAST and Meg Miller, to honor the resiliency and resistance of the Qudiah family, the Khuza’a community, and the Palestinian people.

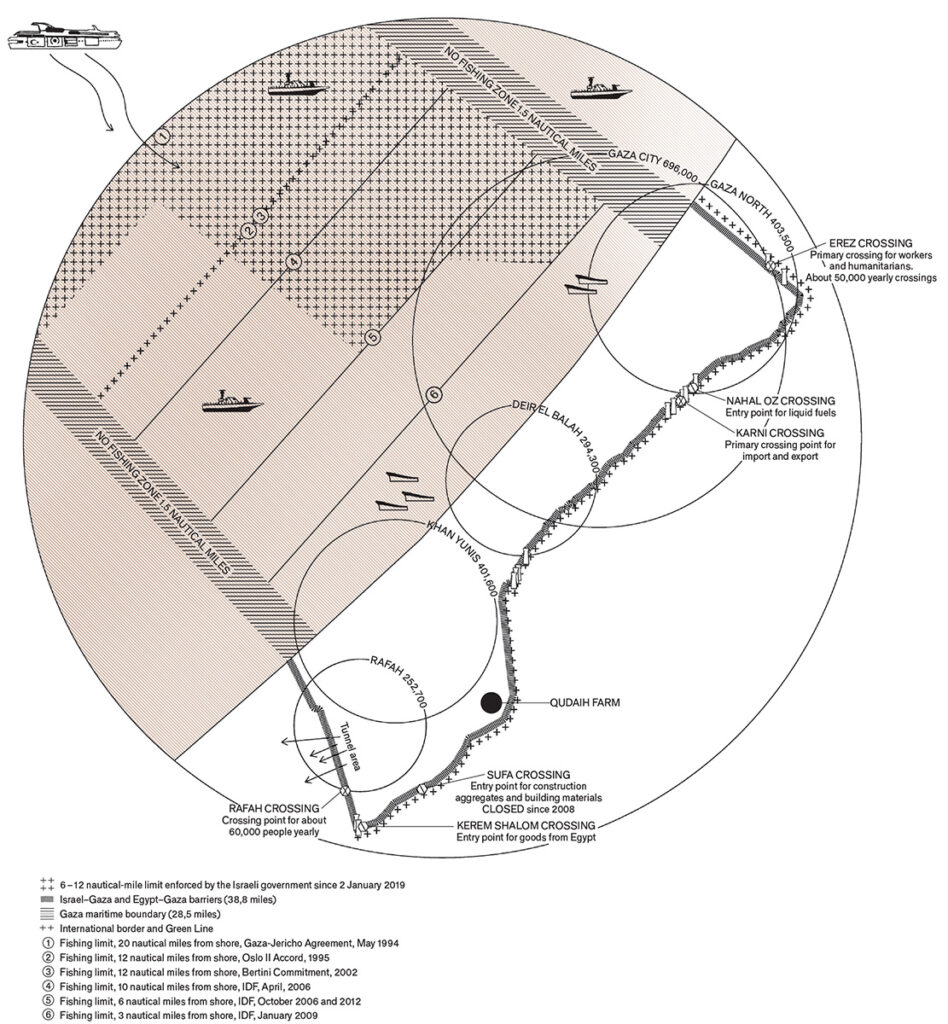

Over two million people—1.4 million of whom are Palestinian refugees—live in the Gaza Strip across 141 square miles, one of the most densely populated geographies in the world. They live with limited access to markets, clean water and electricity, their movement severely restricted by the Israeli blockade following the Hamas takeover after the 2007 Palestinian elections.1 They are enclosed by walls, fencing, buffer zones, cameras and censors—a militarized barrier that wraps the entirety of Gaza’s perimeter.

The Qudaih family lives in the agricultural village of Khuza’a, near one of the most heavily-militarized zones of the border. There, they run a 4,000-square-meter farm that has been in their family for generations. They grow fruits and vegetables and raise livestock, trading for other crops and labor with neighboring farms and producing 90 percent of the food they eat. “In a crisis situation like the Gaza Strip, where 80 percent of the population is dependent on international assistance, this community has managed to be completely self-sufficient—in terms of food production, the way they use energy and the way they capture and harvest rainwater,” says Malkit Shoshan.

Shoshan is an architect and the founder of the think tank FAST, the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory, which focuses on the relationship between architecture, spatial planning and human rights in conflict and post-conflict areas. She became familiar with the Qudaih family through Amir Qudaih, who managed to escape Gaza on a special study visa and is now living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After the two were introduced by one of Shoshan’s students at Harvard, they began a regular correspondence that stretched over the first year of the pandemic.

These conversations have since become the basis for the project Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip, which weaves together, through oral storytelling, illustration and text, the history of the Qudaih family with the history of the Israeli-Palestine conflict.2 Broadly, the project shows the ways the built environment reinforces power dynamics, colonization and oppression, keeping with FAST’s mission to make instances of “spatial violence” visible. More specifically, it tells a more intimate story of one family’s resiliency, over generations, amidst this sustained violence. It also reveals the evolution of the natural ecology of the farm in response to the stressors of war and the “fluctuations in shape and form” of the border that runs alongside it.

“So many political transitions impact [the Quadaih’s] livelihood in such a direct way,” says Shoshan, who was born and raised in Israel and began thinking about the complicity of architecture and urban design in the Israel-Palestine conflict during her studies at the Technion, Israel’s Institute of Technology. “It’s tragic, but at the same time, I love the optimism of this family. For them, life is filled with extreme conditions, which is also a full engagement of being alive.”

The history of the Qudaih farm starts in the early 1900s, after the family settled in Palestine while it was still under Ottoman rule. In 1948, the year Israel officially proclaimed itself a state, the farm switched its main crop from wheat to watermelon. As hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forced to flee their homes and moved into the refugee camps in Gaza—the same camps that still confine their 1.4 million descendents today—the Qudaih family maintained a 16,000-square-meter farm. Today, as Israel’s blockade restricts people’s movements outside of the Gaza Strip, including their access to food markets, the Qudaih family and the Khuza’a farming community swap produce. With little use for money, they trade tomatoes for onions or, when someone needs extra help harvesting, food for labor.

Being farmers and living closely with the land—understanding its natural cycles and seasons—has other advantages. As Israel tightly controls access to resources like water, the Qudaih’s collect and store rainwater to use on their farm all year long. But using their rainwater harvesting system is frequently still risky. Family members must open the tank themselves when it rains, which in the region is usually at night, after Gaza’s Israeli-enforced curfew.

Even with the self-sufficiency of their farm and support of their community, the Qudaihs are still subject to the political conditions that dictate and enforce their enclosure, the fluctuations of violence and periods of relative peace. Around 2005–6, when Israel created a buffer zone within Gaza along the border wall, the Qudaih family’s land was seized and 20 of their olive trees razed. After Hamas took control of Gaza, shelling destroyed the farm’s greenhouse, forcing a shift to harvesting only vegetables that could grow outside. During the 2014 Gaza War, when the village of Khuza’a was badly bombed, the Qudaih family hid in a small room for 21 days, sustaining themselves only on watermelon they had quickly grabbed from the farm as they ran for shelter.

These were all stories Amir Qudaih told Shoshan over their many conversations in 2020. Since Shoshan cannot access Gaza and Amir’s family, like the vast majority of Gazans, cannot leave, Shoshan felt that the only way to “share the complexity of life in Gaza was to try to capture the stories of the people that live there.” To the architect, the thread that runs through these histories—the regional and the personal—is the relationship between power and place, and how space is organized to reinforce certain power dynamics, to separate, extract and enclose.

Yet just as architecture can be a tool to oppress, it can also be used to connect—in this case, it can link the family farm to the Palestinian occupation to the entire history of colonization, then back to the human and the every day life. “Architecture helps you navigate through scale,” she says. “You see how big ideas, ideologies or agendas are being literally materialized in space.” Several of FAST’s projects over the past decade have focused on the Israel-Palestine conflict, which Shoshan considers “testimony to an ethical and moral failure of our society.”

With Border Ecologies, Shoshan took Amir and his family’s stories and placed them, quite literally, within a timeline of the Israel-Palestine conflict. On the project’s website, you can scroll through this timeline and click on Shoshan’s detailed, delicate line drawings to delve further into select topics—Watermelon, Greenhouse, Lionfish—and their associated stories. In 2021, Shoshan brought the Border Ecologies project to the Venice Biennale through an exhibition called Watermelon, Sardines, Crabs, Sand and Sediment. There, the stories were transformed into a 24-foot tablecloth, woven with images and data about the Qudaih farm’s output, survival and circumstances over time.

Shoshan said that she decided to represent this information as a table setting because all of the stories of celebrations revolved around food. During harvest season, at the end of every day, the Khuza’a farmers have a large picnic, for which each farmer brings his own produce to the table. On a larger scale, she says, food was a major factor in this community’s independence from external systems: “Producing their own food is also a source of fulfillment in their lives, because they’re not dependent on these rice bags that come from the UN, but they really cultivate every seed.”

Right before Shoshan and Amir were scheduled to travel for the opening of the Venice Biennale in May 2021, another war broke out between Israel and Palestine. Thirteen Israelis and 256 Palestinians, including 66 children, were killed over the course of 11 days. Shoshan, who had wanted to use the Biennale to bring awareness to the Palestinian plight when no one in the international community seemed to be paying attention, suddenly felt conflicted about the installation—a table-setting-celebration of stories—amid the violence.

“It was incredibly heavy,” she says. “I felt torn.” She was speaking both to her sister in Tel Aviv, who was taking shelter from missile strikes, and the Qudaih family in Gaza, who shared audio recordings with her on WhatsApp with the sound of bombs in the background. She wasn’t in the mood to install and attend the Biennale. “But I spoke to the Qudaih family and they said, ‘We worked on it for such a long time—it’s so important to keep telling the story. Please don’t put it on hold.’” The exhibition ended up winning the Venice Biennale’s Silver Lion award.

Ultimately, the Border Ecologies project is not just about the violence and suffering in the region, but also the resiliency and resistance of this generational family farm. Shoshan’s conversations with Amir moved from discussions about borders and wars to exchanging photos and family recipes. Even with FAST’s mission to make systems of extraction and oppression visible, “at the same time,” Shoshan says, “we advocate for alternatives.” The self-sufficiency of the Qudaihs and their Khuza’a community—their knowledge of the soil, preservation of the seeds and closeness with the animals—is presented as a blueprint for solidarity and survival, and an example of a world imagined otherwise.

“If you think about an imagination of what society could be—and I’m taking away the war and all the violence for a second, because no one should live like that—there is something very beautiful in the solidarity amongst the people that live [in Khuza’a],” says Shoshan. “Their survival is completely dependent on the survival of the other farmers…I think that was incredibly inspiring, together with their spirit, because there is a lot of fear and trauma from the war, but there is so much beauty in their joy of life, and celebration of life, regardless.”