This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Order your copy here.

Urban agriculture will never be able to feed the cities of the future. At least not completely. This fact has been proven time and again by researchers and scientists, who point to spatial limitations and nutrient-poor soil as barriers to the self-sufficient city. However, for any urban dweller who may have once tended to a window sill basil plant or grown tomato vines in a community allotment, there are clear benefits to growing food in the city—beyond filling one’s belly. To better describe the unique social and political progress that accompanies urban food production, Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro and George Martin, co-authors ofUrban Food Production for Ecosocialism, have proposed using the alternative term “urban cultivation.”

“Where there is soil there is the potential for transformation.”

Last spring, I attended a free, open course at the People’s Forum NYC instructed by ProfessorEngel-Di Mauro called “Socialism, Science and Struggle.” Each week, scientists, activists, healers, urban farmers and students gathered to discuss how nature and the natural sciences, particularly soil science, might be grounded in Marxist methodology. Most illuminating was the use of principles of soil formation to illustrate concepts of dialectical materialism, the organizing Marxist philosophy on matter.1 It was through these conversations that I also began to understand why the need to cultivate, in spite of inhospitable conditions and polluted land, persists. Where there is soil there is the potential for transformation.

- 1Dialectical Materialism is a philosophy that argues that everything that exists is material and is derived from matter; that matter is in a process and constant change; and that all matter is interconnected and interdependent.

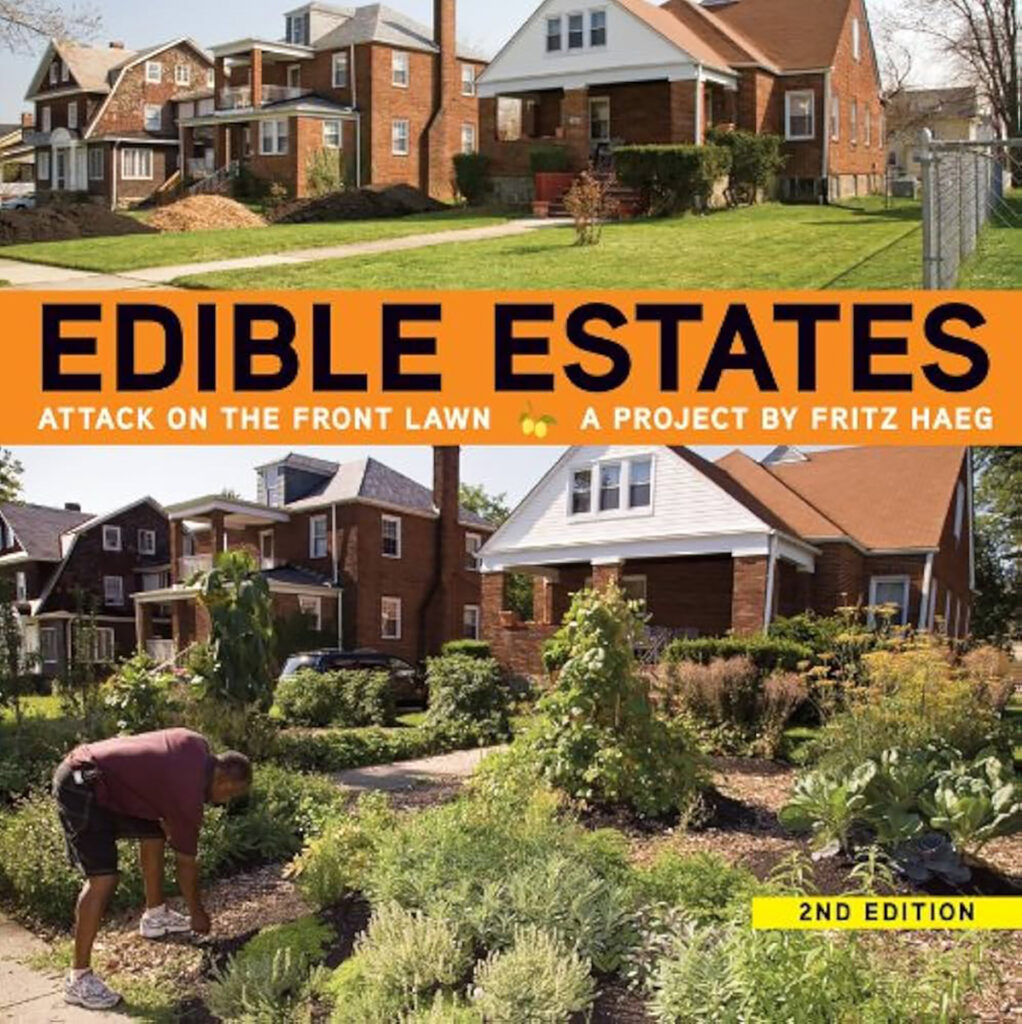

In 2005, the architect-turned-artist Fritz Haeg broke ground on the first lawn in his Edible Estates series. The initiative reimagined the typically sterile, manicured lawn as a site for dynamic interactions between humans and their environment. Over the next seven years, Haeg would transform lawns from Kansas to Aarhus into biologically diverse ecosystems, trading sod for intricate networks of native and edible plants. In a 2021 essay for Frieze, Haeg, who now runs the experimental Northern California artist commune Salmon Creek Farms, wrote that food attunes us to “relationships between…pollinators and their forage, soils and their organisms, air and rain, streams and oceans, even toilets and trash dumps.” In Edible Estate’s initial artist statement, Haeg professed to have sought out visually monotonous landscapes in hopes that this edible landscapes would serve as spatial disruptions.2 Messy, abundant, and often beautiful, his lawns were designed as a challenge to each project’s surrounding community, an invitation to tap into a collective imagination that asks for more from our urban spaces.

The dream for the edible city may be more ubiquitous than we think. While current urban food production initiatives are often mired by the pressures of real estate and bureaucratic red tape, one does not have to look too far back to find precedence for urban food initiatives and infrastructures within our very own neighborhoods. For example, visitors to New York City park such as Fort Greene and McCarren Park might be surprised to find that these green spaces were once designed to house flourishing urban educational farms. In 1902, Francis Griscom Parsons, a Brooklyn-based mother to seven, founded an experimental children’s farm on a public lot in what was then colloquially referred to as Hell’s Kitchen. The success of the farm sparked the school garden movement in New York City, which advocated for the belief that access to open space, the right to play, and the skills to grow one’s own food were inextricable from one’s humanity and thus necessary to ensure that children grew up to be good citizens. However, physical evidence of this historical instance in which a municipality prioritized food sovereignty no longer exists—the gardens were dismantled after the boom and bust of the victory gardens of World War I.

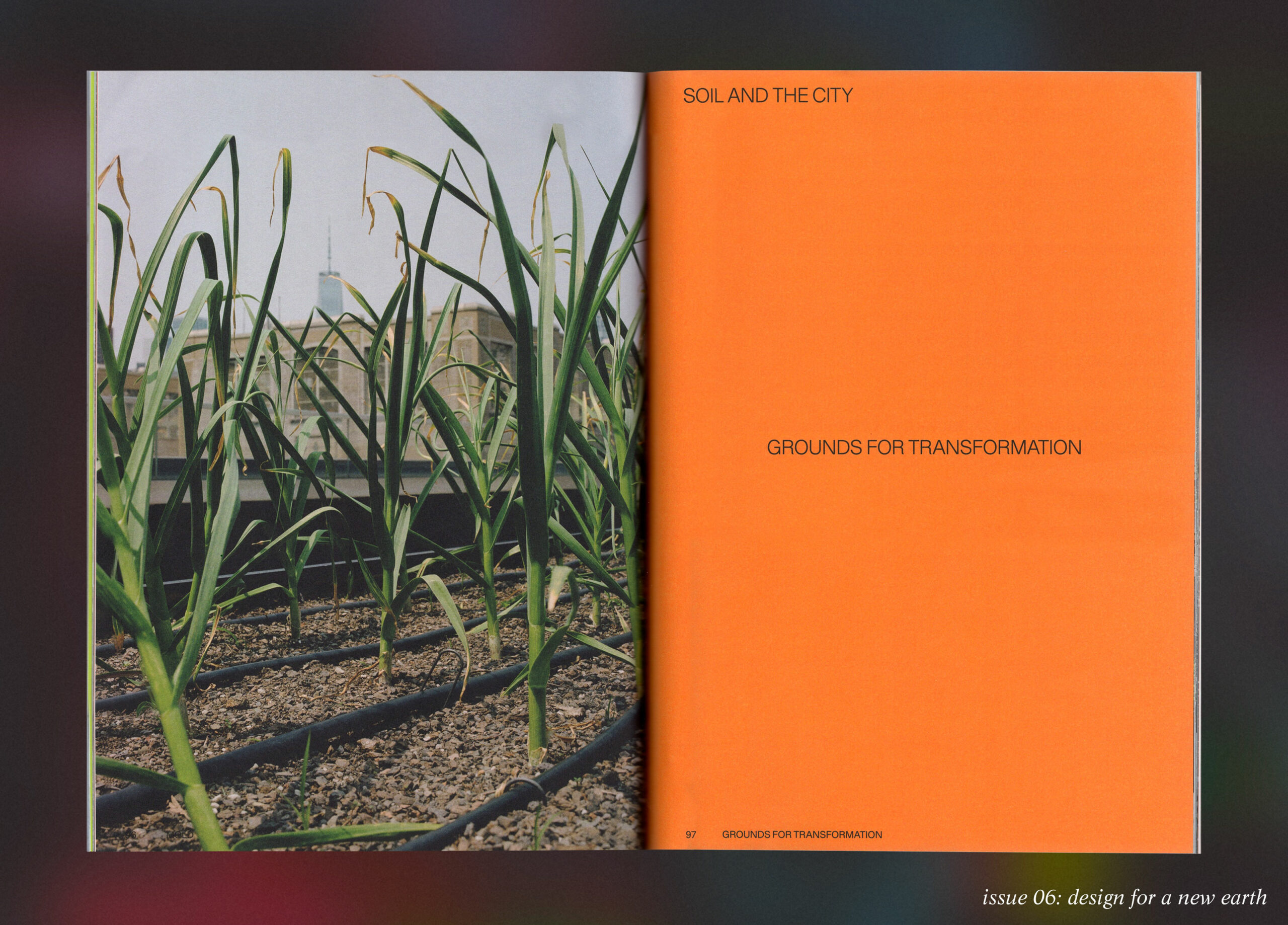

That is not to say that the dream does not persist. Today, New York City manages about 30,000 acres of public parkland, a far cry from the 100 acres of community gardens that are currently available to city residents. In 2016, in response to this statistic and the lack of urban access to fresh food, the artist Mary Mattingly launched a floating food forest in the Bronx River. Titled Swale, Mattingly’s work blanketed the surface of a 5,000-square-foot barge with a tangle of fruit trees, vegetables, herbs and edible flowers, encouraging visitors to harvest as they explored the forest. As a water-bound project, Swale sought to subvert a decades-old city ordinance, initially instituted to protect plants from overzealous picking, that makes foraging on public land illegal. While Mattingly is currently working on the next permanent iteration of Swale (the project came to a close in 2019), the project has already begun to re-shape the city. In 2017, the Bronx River Foodway opened in Concrete Plant Park, where the food forest had previously docked, becoming the first foraging park in New York City. Elsewhere in the city, other initiatives such as Project EATS and Oko Farms have found ways to carve out space for food production to provide not only fresh food but also education around food systems to their local communities. Located along the East River, Oko Farms draws from traditional ecological knowledge in their urban aquaponic farming practice, creating cycles of symbiosis between their crops and the fish that fertilize them. Meanwhile Project EATS, an organization that started as an extension of founder Linda Goode Bryant’s artistic practice, has taken to rooftops and vacant lots, establishing farms across Brooklyn, Lower Manhattan, and the Bronx with the intention of empowering communities to grow their food where they live.

In tandem with the rooftop gardens and community lots that most people might associate with urban food production, edible landscapes and food forests offer a vision for a future in which food (and medicine) are de commodified. Most modern-day edible landscapes and food forests are designed according to the cyclical principles of agroforestry and permaculture, which mimic the self-sustaining relationships that constitute naturally occurring forests. Asheville’s Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Park, one of the oldest food forests in the US, is almost undetectable to the untrained eye. Founded in 1997 on the site of a demolished high school that had served Black students during segregation, the forest was seeded in hopes of increasing access to fresh produce in a neighborhood food desert. Today, visitors are able to pluck apples and chestnuts for snacking, and the forest canopy is maintained by a group of local volunteers.

In Seattle, a more conspicuous landscape unfolds at the Beacon Hill Food Forest, which has been in operation for over ten years. Helix and spiral-shaped herb and vegetable gardens lead to a canopied food forest where community members are invited to take what they like: a public harvest. In choosing to sow self-sustaining ecosystems, food forests like Beacon Hill and George Washington Carver not only feed their communities but also manifest a more resilient future for the edible city, one that accounts for labor and resources, or rather, a lack thereof. These initiatives ask, what might abundance look like where we are and with what we already have?

It is this same sentiment that has spurred the formation of the Edible Cities Network, an EU-funded initiative to transform public spaces into food hubs in cities across Europe. In over 150 cities, previously overgrown parks, plazas and even moats have been turned over for public cultivation to feed local communities. The implementation of policy points to a greater wave of formal, institutional support for a movement whose history has typically been rooted in informal, often guerilla tactics for reclaiming urban land.

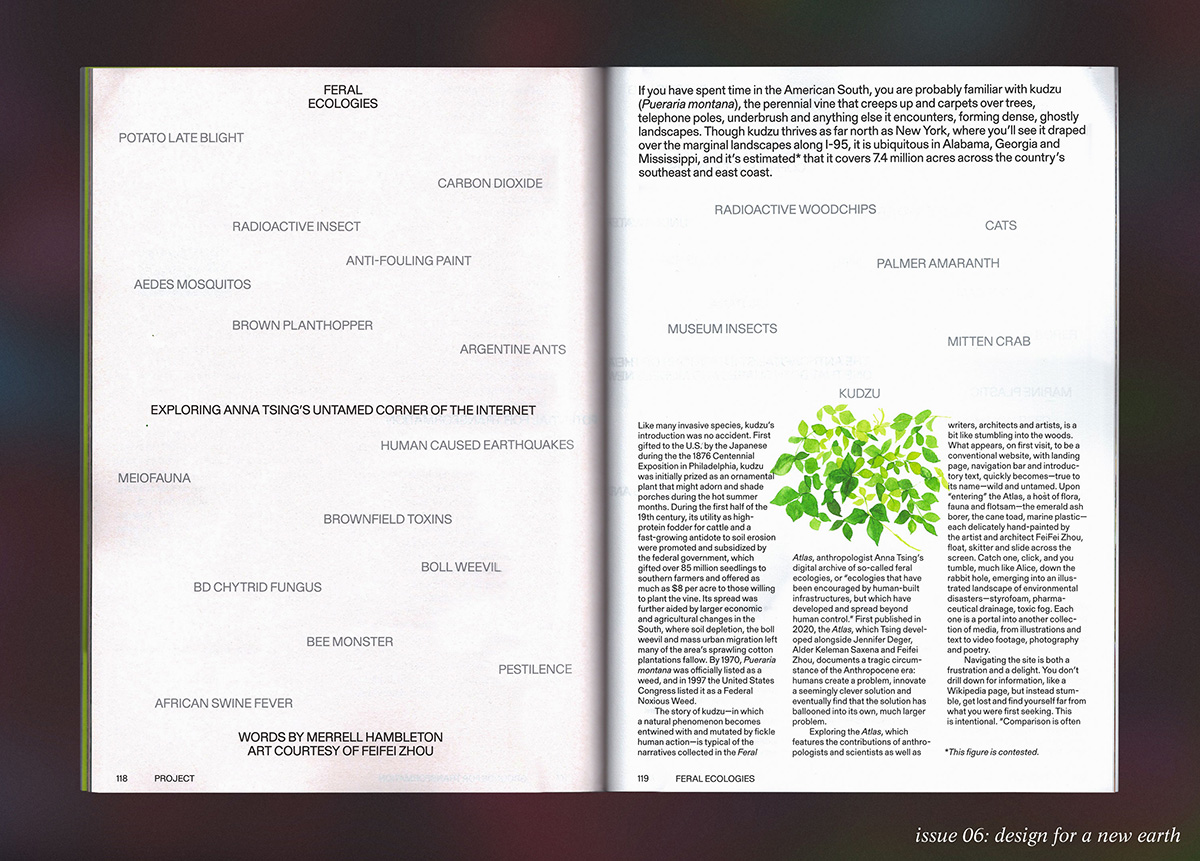

In truth, edible cities have always existed. The milpas and food forests that once sustained the ancient Mayan city of El Pilar continue to be stewarded by forest gardeners eight millenia later. In Mesopotamia, the earliest recorded examples of food scaping occurred when Babylonians and Assyrians incorporated gardens of fruit trees and edible plants across the city, a physical manifestation of Paradise on earth. Even when European colonizers settled North America, what appeared to them to be unconquered wilderness often comprised carefully cultivated Indigenous food forests attuned to the interconnected relationships between various food-bearing plants and trees. By dislodging food from the capitalist agricultural systems that normally dictate its consumption, the drive for the edible city brings us eye-to-eye with the very stem, bush, or tree we rely on for sustenance. The intimacy of ingestion requires a deeper awareness of the confluence of social and environmental factors that have converged to produce a head of lettuce or a handful of strawberries. Questions of water, sunlight, and soil are tied up in urban processes, and the act of cultivation locates us as inheritors to an often polluted land.

On a rainy Sunday afternoon, my fellow classmates from “Socialism, Science and Struggle” and I trekked to the Friends of Flowers Community Garden in Flatbush. As a culmination of the course, we were participating in a scientific practicum and would be taking soil samples in order to identify the various elements and characteristics of the garden’s soil. While taking shelter from the drizzle in the garden’s gazebo, conversations soon turned toward the barriers that often accompany growing your own food in the city: urban soil might contain poisonous toxins and require rehabilitation, and in some states, collecting rainwater is illegal. In considering the stewardship required for the future of edible cities and the hurdles that must be overcome, we might return to the philosophies of the revolutionary Amilcar Cabral who believed that the key to liberation lay within soil. His training as an agronomist in Portuguese-occupied Guinea-Bisseau provided him with an intimate understanding of the region’s geography and agricultural practices, which served as a grounding for his strategies for revolution. For Cabral, it was clear that the soil was not static, but rather in “dynamic relation to human social structures.” In short, soil is a grounds for change; even in our cities, it is a reflection of our own communities and histories, and the sediment from which change takes root.

- 1Dialectical Materialism is a philosophy that argues that everything that exists is material and is derived from matter; that matter is in a process and constant change; and that all matter is interconnected and interdependent.