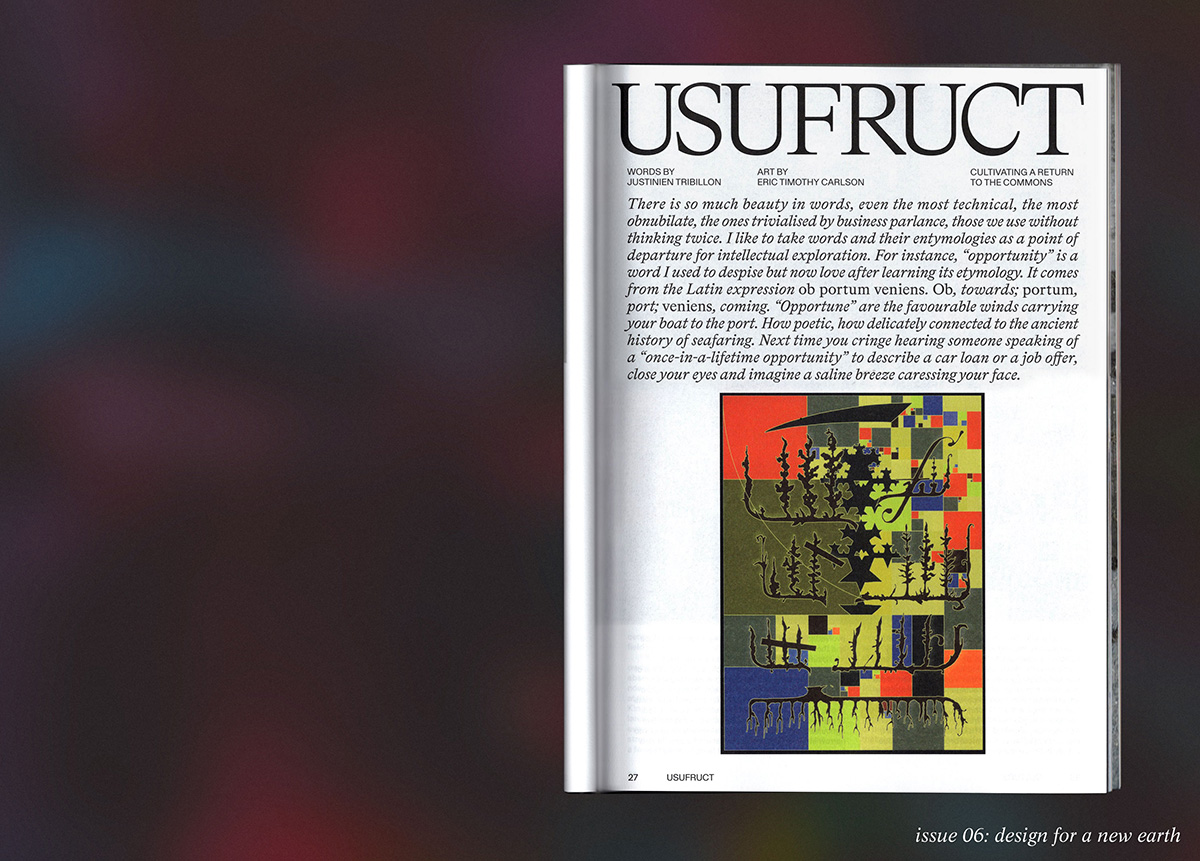

This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Pre-Order your copy here.

I had been vegan for five years when it stopped making any sense. Like many people in the United States who make this decision, I found the conditions of factory farming abhorrent and thought the only way not to support these corporate enterprises would be to completely remove animal products from my diet. That’s what I did in 2011, forgoing lamb chops and omelets without a second thought. But I was living in Brooklyn then, eating at farm-to-table restaurants serving free-range eggs and artisan cheeses—what was I gaining by rejecting these? Why was I making a cashew queso in my kitchen from nuts likely sourced through deeply inhumane labor practices that leave women’s fingers burned from anacardic acid on the shell1 rather than finding a high-quality, locally produced cheese?

- 1 Per Slow Food, “Over half of the world’s new cashew production is concentrated in just three countries: Vietnam, India, and the Ivory Coast [sic]. The industry in each country, however, is marked by dangerous conditions and poverty-line wages for workers.”

The answer was that I hadn’t yet become aware of the conditions of cashew cultivation, and I really thought I could fair-trade and organic and vegan my way out of having any sort of footprint on the planet. For a lot of ethical vegans, it’s believed that animals are here on earth for reasons that are separate from their usefulness to humans; this is why they don’t eat them, neither their flesh nor their milk, and this is why they don’t wear their skin as a handbag or pair of loafers. Peter Singer, author of the 1975 book Animal Liberation , which coined the term “speciesism,” advocates for veganism on the grounds of utilitarianism, an ethical position that judges an action good or bad on the basis of whether or not it causes pain or promotes happiness. This makes sense to me as a philosophical proposition, but I stopped believing in it as the grounds for deciding what I should eat. To me, it had become clear that animals and humans were interdependent, both responsible for the maintenance of soil and the care of each other. It’s a more context-dependent perspective, and what happened is that I came to believe food is context-dependent. I’ve embraced an idea of “conditional consumption” that sees me trying to simply be mindful of how what I eat fits into my local economy and environment.

Of course, caring for the soil or the animals is not central to the work of factory farms, and as someone who doesn’t eat meat, I don’t see care in slaughter at any scale—though I know that there are ex-vegans who go straight from pressing tofu to whole-animal butchery.2 But because I had come to be a person who ate locally and seasonally aside from the very ethically dubious imported cashews, coconuts and palm oil3 that sustain many U.S. vegans, it had become clear to me that there is a middle ground: one where we can enjoy the nutrients present in eggs harvested from free-range chickens and in cheeses fermented through centuries-old practices by farmers who don’t necessarily hold dominion over the animals’ very existence. This is an obvious thought to most, probably. It became an obvious thought to me through learning about agroecology, a holistic approach to agriculture that prioritizes the environment and social concerns around well-being, livelihood and cultural tradition.

- 2 “Before she was a butcher, Ms. Kavanaugh was a strict vegetarian,” wrote the New York Times in a 2019 piece titled, “The Vegetarians Who Turned Into Butchers.”

- 3 “The attacks on the villagers of SPFT are far from isolated incidents in the broader struggle over land rights in Thailand: At least 70 land rights lawyers and community activists have vanished or been confirmed dead over the past few decades,” writes Diana Hubbell at Eater about palm oil.

In 2018, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations put out a brief on the role of livestock in agroecological farming,4 finding that “of the 770 million people surviving on less than USD 1.90 per day, about half depend directly on livestock for their livelihoods.” More than half of the world’s rural households own livestock, which provide income through short, local supply chains and convert items inedible to humans like grass and straw into food and fertilizer. Agroecological livestock practices also increase plant diversity in grasslands.5

- 4 “Livestock are key to the livelihoods of small-scale farmers, particularly women, providing them with income, capital, fertilizer, fuel, draught power, fibres and hides,” says the FAO’s report.

- 5 The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

These realities have challenged me. Large-scale, intensive industrial factory farming, which is subsidized in the United States with $38 billion per year, is the issue, not small-scale farmers who are working with little resources but contributing positively to local ecology and economies. I don’t want to see animals killed or used or suffering; I wouldn’t and still won’t eat from products made from animals if I know they have been. But who am I? And why does my comfort matter so much?

In When Species Meet, the philosopher Donna Haraway writes:

“In principle if not always in personal and collective action, it is easy to know that factory farming and its sciences and politics must be undone. But what then? How can food security for everybody (not just for the rich, who can forget how important cheap and abundant food is) and multispecies’ coflourishing be linked in practice? How can remembering the conquest of the western states by Anglo settlers and their plants and animals become part of the solution and not another occasion for the pleasurable and individualizing frisson of guilt?”

Considering Haraway’s “frisson of guilt”; deprioritizing my own comfort when considering food system problems; and understanding that the decisions I make about what I eat are going to change depending on where I am and what is customary; have led me into what often feels like murky ethical territory: eating eggs and cheese here, slurping oysters and mussels over there. But that’s only murky if I consider the consistent identity of “vegan” or “vegetarian” to be more important than ecological and cultural reality, to be more significant than “multispecies coflourishing” is for the care of the soil. This is what Naisargi Dave, a vegan anthropologist, calls “the tyranny of consistency” in Messy Eating: Conversations on Animals as Food, where identity takes on more meaning than practice for those making non-normative choices.

I can now admit I went vegan first to save myself from complexities I preferred not to see, when no matter what I personally decide, complexities will always be there. Conditional consumption is a richer way to eat, literally and figuratively, and to think about food. In embracing conditional consumption, I become of the world rather than set apart.

- 1 Per Slow Food, “Over half of the world’s new cashew production is concentrated in just three countries: Vietnam, India, and the Ivory Coast [sic]. The industry in each country, however, is marked by dangerous conditions and poverty-line wages for workers.”

- 2 “Before she was a butcher, Ms. Kavanaugh was a strict vegetarian,” wrote the New York Times in a 2019 piece titled, “The Vegetarians Who Turned Into Butchers.”

- 3 “The attacks on the villagers of SPFT are far from isolated incidents in the broader struggle over land rights in Thailand: At least 70 land rights lawyers and community activists have vanished or been confirmed dead over the past few decades,” writes Diana Hubbell at Eater about palm oil.

- 4 “Livestock are key to the livelihoods of small-scale farmers, particularly women, providing them with income, capital, fertilizer, fuel, draught power, fibres and hides,” says the FAO’s report.

- 5 The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.