This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Order your copy here.

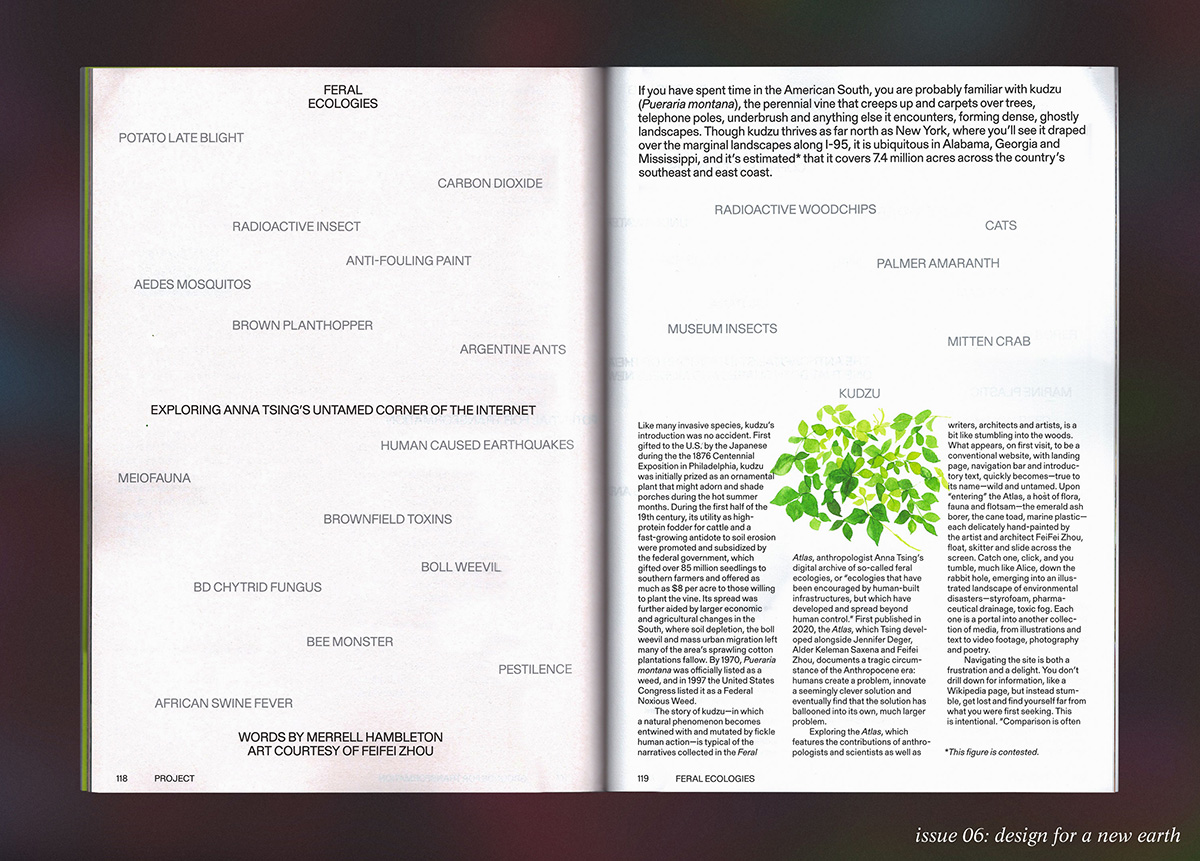

If you have spent time in the American South, you are probably familiar with kudzu (Pueraria montana), the perennial vine that creeps up and carpets over trees, telephone poles, underbrush and anything else it encounters, forming dense, ghostly landscapes. Though kudzu thrives as far north as New York, where you’ll see it draped over the marginal landscapes along I-95, it is ubiquitous in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, and it’s estimated1 that it covers 7.4 million acres across the country’s southeast and east coast.

- 1 This figure is contested.

Like many invasive species, kudzu’s introduction was no accident. First gifted to the U.S. by the Japanese during the the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, kudzu was initially prized as an ornamental plant that might adorn and shade porches during the hot summer months. During the first half of the 19th century, its utility as high-protein fodder for cattle and a fast-growing antidote to soil erosion were promoted and subsidized by the federal government, which gifted over 85 million seedlings to southern farmers and offered as much as $8 per acre to those willing to plant the vine. Its spread was further aided by larger economic and agricultural changes in the South, where soil depletion, the boll weevil and mass urban migration left many of the area’s sprawling cotton plantations fallow. By 1970, Pueraria montana was officially listed as a weed, and in 1997 the United States Congress listed it as a Federal Noxious Weed.

The story of kudzu—in which a natural phenomenon becomes entwined with and mutated by fickle human action—is typical of the narratives collected in the Feral Atlas, anthropologist Anna Tsing’s digital archive of so-called feral ecologies, or “ecologies that have been encouraged by human-built infrastructures, but which have developed and spread beyond human control.” First published in 2020, the Atlas, which Tsing developed alongside Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena and Feifei Zhou, documents a tragic circumstance of the Anthropocene era: humans create a problem, innovate a seemingly clever solution and eventually find that the solution has ballooned into its own, much larger problem.

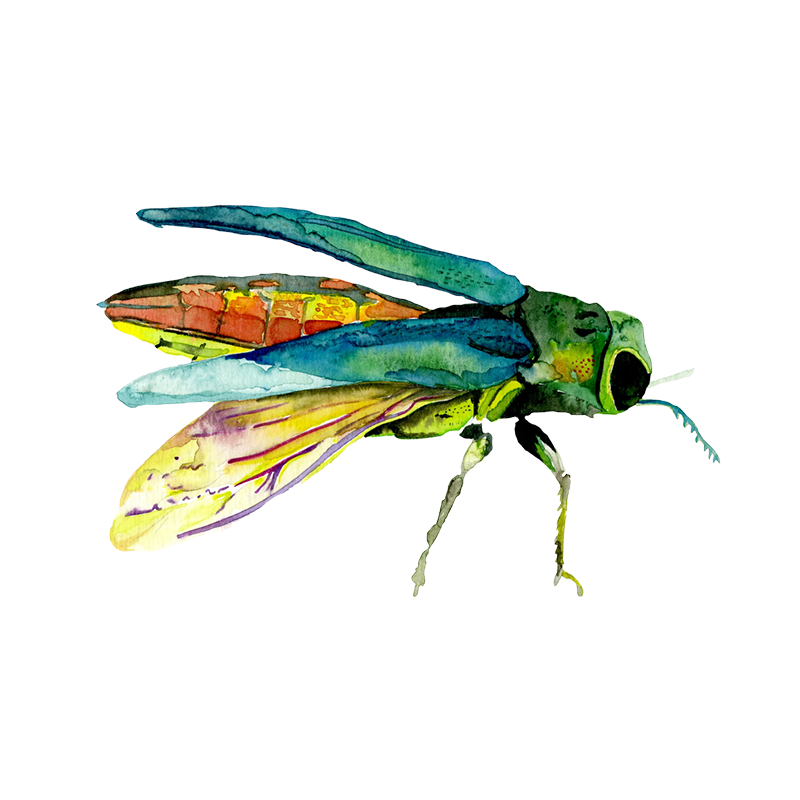

Exploring the Atlas, which features the contributions of anthropologists and scientists as well as writers, architects and artists, is a bit like stumbling into the woods. What appears, on first visit, to be a conventional website, with landing page, navigation bar and introductory text, quickly becomes—true to its name—wild and untamed. Upon “entering” the Atlas, a host of flora, fauna and flotsam—the emerald ash borer, the cane toad, marine plastic—each delicately hand-painted by the artist and architect FeiFei Zhou, float, skitter and slide across the screen. Catch one, click, and you tumble, much like Alice, down the rabbit hole, emerging into an illustrated landscape of environmental disasters—styrofoam, pharmaceutical drainage, toxic fog. Each one is a portal into another collection of media, from illustrations and text to video footage, photography and poetry.

Navigating the site is both a frustration and a delight. You don’t drill down for information, like a Wikipedia page, but instead stumble, get lost and find yourself far from what you were first seeking. This is intentional. “Comparison is often identified as a tool of colonial power,” says Tsing. “We wanted to bring all these different stories together, using the classification tools of the digital, but without forming these deeply enclosed boxes that you couldn’t get out of.” Though the Atlas is rich with data, it’s not conventionally mapped but rather hand-drawn, soft and shifting. “To convey the dynamics of this feral ecology, we wanted to show movement,” she says. “GIS maps presume that all scales are compatible, which they aren’t necessarily, and that location is the key issue, rather than, say, movement or points of attachment or temporal processes.”

Like someone offering directions to a lost traveler, Tsing instructs me on how to find a particularly well-hidden treasure: “Once you’re at kudzu, click into Elaine Schmidt’s entry. Scroll down to the ‘feral qualities.’ You’ll see a green line. If you press it, you’ll find an amazing piece by Mississippi poet Beth Anne Fennelly.” I do as I’m instructed. I find a poem: “I asked a neighbor, early on, if there was a way to get rid of it,” writes Fennelly. “Well, he said, over the kudzu fence, I suppose if you sprayed it with whiskey, maybe the Baptists would eat it.” There’s an intimacy to this content, shared alongside the hard facts, that fixes the Atlas’s reports in one’s mind. “The entries are very locally embedded and engaged,” says Tsing. “There is a lot of poetry in the Feral Atlas, and it’s really hard to find.”

The anti-capitalist intentions of the Atlas make it a novel, radical project—one that both shares and models new modes of engaging with information. It’s a timely contribution, as scholars like Katherine McKittrick and Saidya Hartman question traditional methodology, writ large. But the format and function of the Atlas have also been barriers to its acceptance. “The wonderful part is that artists and architects have been interested in what we’re doing,” says Tsing. “The disappointing part is that Anthropocene scholars haven’t been able to read it.” Many of her colleagues, she says, were “unhappy with the playfulness with which we approached how to learn.”

To address this, Tsing and her co-authors have just completed a companion book that will serve as both a guide to and expansion on the content and conceptual frameworks of the Atlas. Why conform to the more conservative tastes that she’s worked so hard to circumvent? Ultimately, Tsing’s commitment is to building a new field, one that’s capable of comprehending what she calls “the patchy anthropocene.” “We need the techniques of the natural scientists and humanists and the arts in order to do the basic descriptive work,” she says.

- 1 This figure is contested.