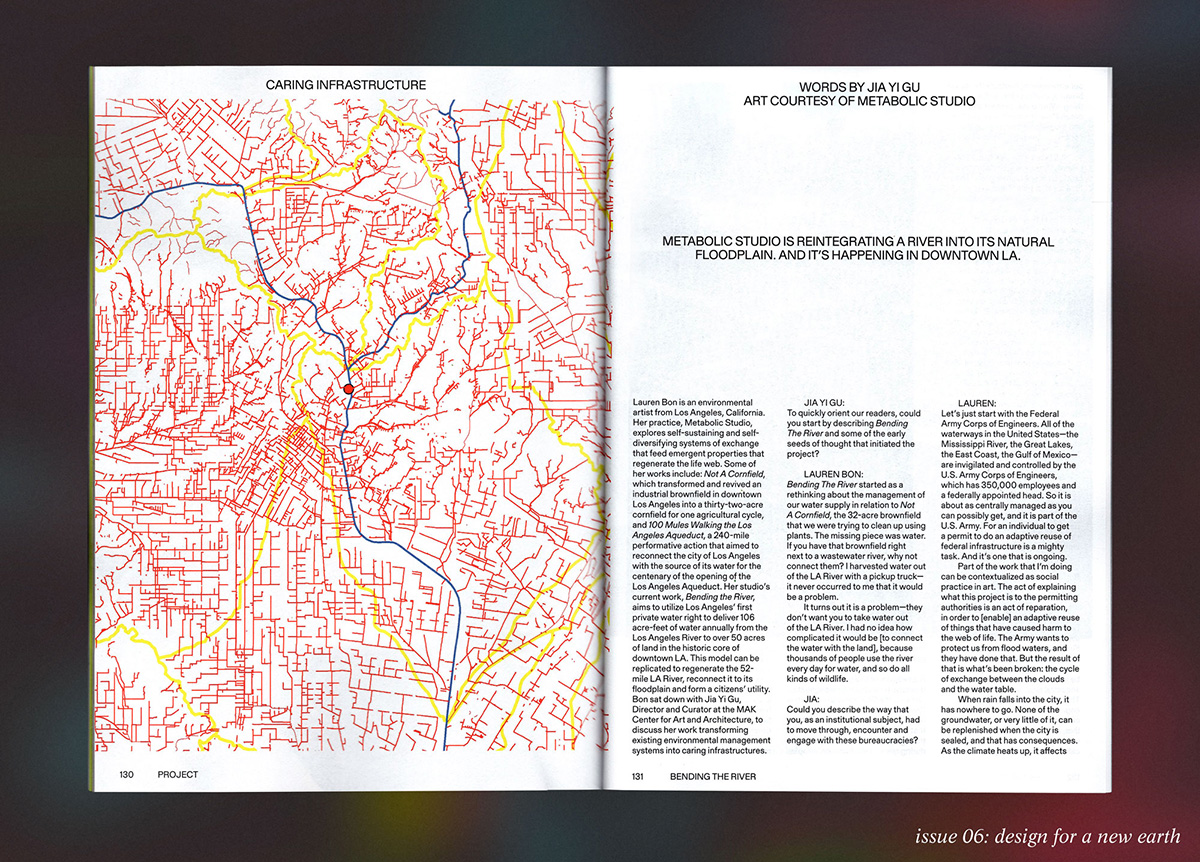

This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Order your copy here.

Lauren Bon is an environmental artist from Los Angeles, California. Her practice, Metabolic Studio, explores self-sustaining and self-diversifying systems of exchange that feed emergent properties that regenerate the life web. Some of her works include: Not A Cornfield, which transformed and revived an industrial brownfield in downtown Los Angeles into a thirty-two-acre cornfield for one agricultural cycle, and 100 Mules Walking the Los Angeles Aqueduct, a 240-mile performative action that aimed to reconnect the city of Los Angeles with the source of its water for the centenary of the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Her studio’s current work, Bending the River, aims to utilize Los Angeles’ first private water right to deliver 106 acre-feet of water annually from the Los Angeles River to over 50 acres of land in the historic core of downtown LA. This model can be replicated to regenerate the 52-mile LA River, reconnect it to its floodplain and form a citizens’ utility. Bon sat down with Jia Yi Gu, Director and Curator at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, to discuss her work transforming existing environmental management systems into caring infrastructures.

Jia Yi Gu:

To quickly orient our readers, could you start by describing Bending The River and some of the early seeds of thought that initiated the project?

Lauren Bon:

Bending The River started as a rethinking about the management of our water supply in relation to Not A Cornfield, the 32-acre brownfield that we were trying to clean up using plants. The missing piece was water. If you have that brownfield right next to a wastewater river, why not connect them? I harvested water out of the LA River with a pickup truck—it never occurred to me that it would be a problem.

It turns out it is a problem—they don’t want you to take water out of the LA River. I had no idea how complicated it would be [to connect the water with the land], because thousands of people use the river every day for water, and so do all kinds of wildlife.

JYG:

Could you describe the way that you, as an institutional subject, had to move through, encounter and engage with these bureaucracies?

LB:

Let’s just start with the Federal Army Corps of Engineers. All of the waterways in the United States—the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, the East Coast, the Gulf of Mexico—are invigilated and controlled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which has 350,000 employees and a federally appointed head. So it is about as centrally managed as you can possibly get, and it is part of the U.S. Army. For an individual to get a permit to do an adaptive reuse of federal infrastructure is a mighty task. And it’s one that is ongoing.

Part of the work that I’m doing can be contextualized as social practice in art. The act of explaining what this project is to the permitting authorities is an act of reparation, in order to [enable] an adaptive reuse of things that have caused harm to the web of life. The Army wants to protect us from flood waters, and they have done that. But the result of that is what’s been broken: the cycle of exchange between the clouds and the water table.

When rain falls into the city, it has nowhere to go. None of the groundwater, or very little of it, can be replenished when the city is sealed, and that has consequences. As the climate heats up, it affects our atmosphere, it affects the air we breathe, it affects fire, soil, everything. What does “protect and defend” mean when the protection and the defense are creating the context for the possible need to leave the city altogether?

It’s taken a decade to get these seventy-three federal, state and local permits, which is a very long time for an artwork, and a very normal time for an infrastructural project.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is the entity which is responsible for the fifty-one miles of concrete that we call the LA River, but all of the other things that go into the river and underneath the concrete belong to the City of Los Angeles. When you’re doing an adaptive reuse of infrastructure, you need both the Army Corps of Engineers permits and the City of LA permits to dig under the concrete. In our case, the adaptation is 300 feet of vitrified clay pipe, which redirects the low-flow channel of the LA River from its course out to sea. A small portion of the low-flow channel flows into the pipe, and then through that, it’s conveyed under the Southern Pacific railway lines, so that’s another permit. Then you need a permit to dig a tunnel under the Southern Pacific railway to the Metabolic Studio so that you can lift the water from forty feet below the city grade so that it can be cleansed before it’s distributed.

JYG:

Asking permissions seems to be a part of your project. Who do you seek permission from to enable the work of Bending The River?

LB:

Before you get anywhere, you’ve got the U.S. Army Corps, City of LA, Union Pacific railway line—and there is the importance of getting permission from the Tongva and Gabrielino. It’s been critical for us to ask permission of people from the First Nations community, because once you open up the infrastructure, and dig through the land, you might be looking at ancestral objects, ancestral land, ancestral artifacts. That’s been a whole process of engagement over years and years of cultural monitoring, and more than that, conversation about reparation work and the meaning of what we call the river. The thing that we call the river is not what the First Nations people call the river.

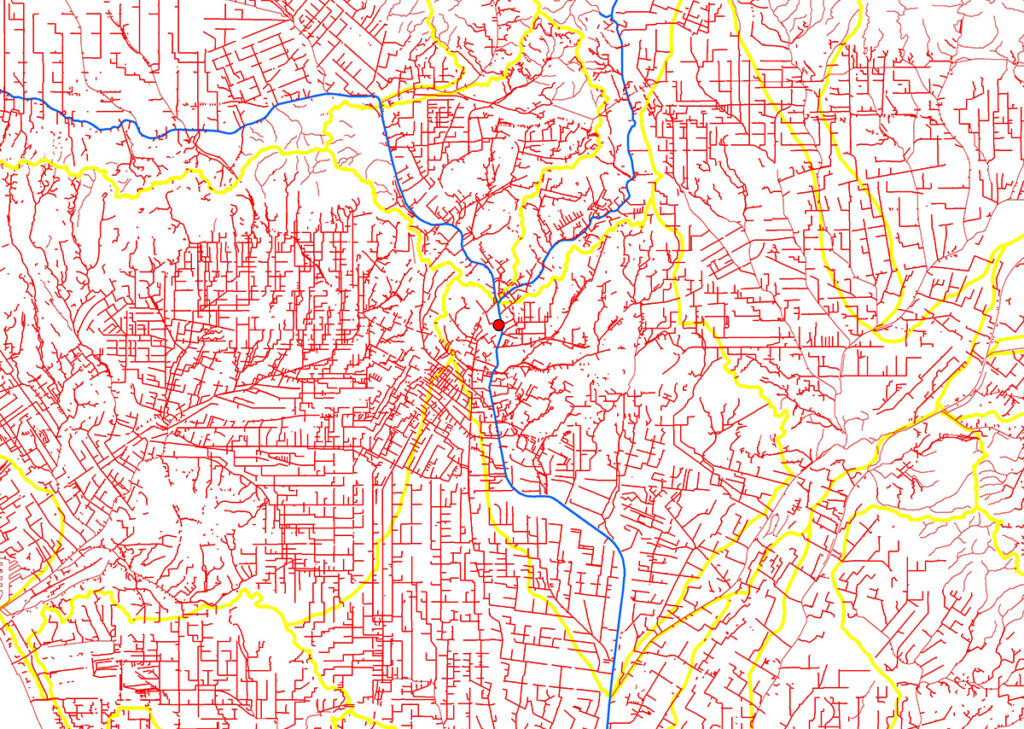

For First Nations people, there is a network of five geological drainage basins that interconnect just past the Glendale Narrows.1 Where the LA State Historic Park is now would have been full of debris that would have been pushed through the Glendale Narrows during rain events. For tribal people, the LA State Historic Park is part of the unbridled river that would normally have flooded. Not A Cornfield was, in many ways, the beginning of coming to understand why that place was so fertile. There would have been these disturbance events from floods that would have brought down soil, wood, rock, sand, seed, duff and dander, and it would’ve made that basin particularly fertile.

When the city became colonized, we decided to put our train yard right on top of the most fertile land in this network of interlocking glacial basins.

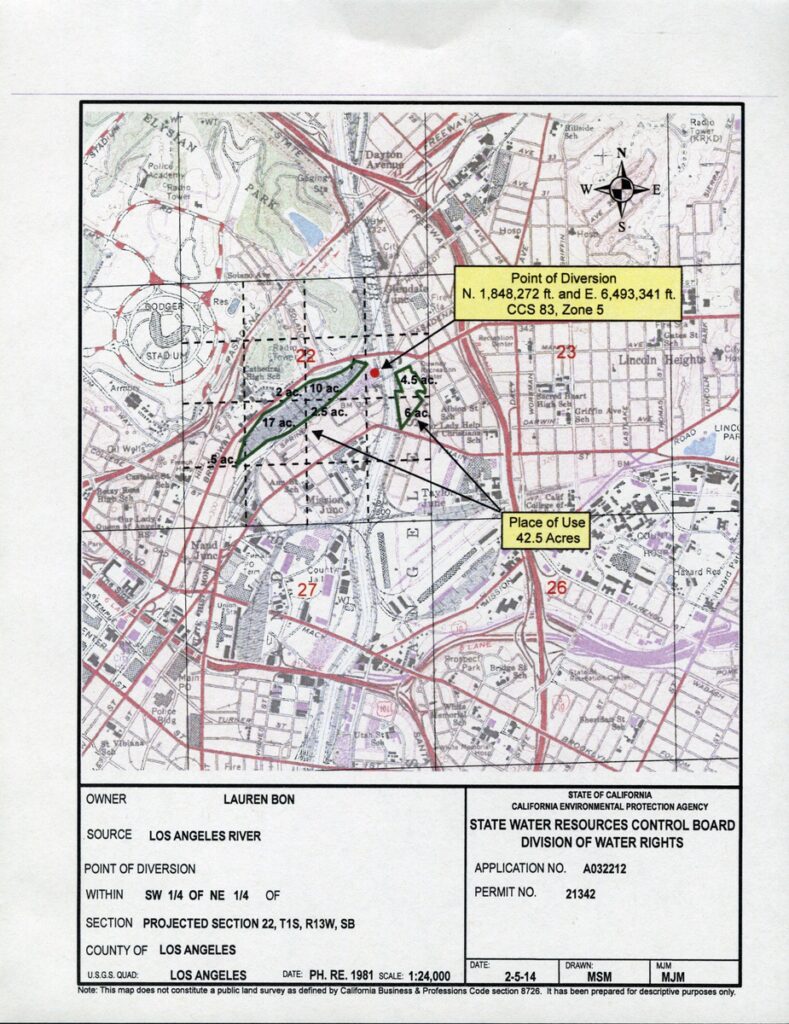

Once you’ve got the infrastructure and the design in, the permits, and the tribal monitoring, you still run into the problem of, “Whose water is this?” There are no private water rights in the City of LA. There’s only one water right in LA, and it’s held by the LADWP (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power). I had to apply for a California State water right, and I got it. The problem with the private water right is that, fundamentally as a reparation work, one has to go back to the thinking of the pre-colonial city, where land ownership and water ownership is something we want to get past.

- 1 An eleven-mile stretch along the Los Angeles River that is adjacent to Glendale, Griffith Park, Los Feliz, Atwater Village and Elysian Valley.

My water right is number 21432. That means that there are 21,000 water rights in the state of California. But this is the first private water in LA. When you go into the Central Valley and you see people growing fruit or almond trees or things for massive farms, most of those people probably have water rights. So it’s not like water rights are that impossible to get, but you have to explain why you need one. What is the incentive? In this particular case, the incentive is to irrigate a 50-acre parcel of public space that is the Los Angeles State Historic Park, the Albion Park on the other side of the Spring Street Bridge as well as a few other properties. We have a ten-year water sharing agreement with the California State Historic Park, which means that what used to be the floodplain of the LA River will be the floodplain again.

It’s important that the water right becomes a community asset. Metabolic Studio is currently working on the potential forming of a DAO (decentralized autonomous organization) to manage my water right, including making decisions about how the water is used and distributed. These promising developments are occurring with the development of the next generation of the World Wide Web, which is expected to be more decentralized and include smart contracts, which are self-executing with the terms of the agreements and transactions transparent and visible to everyone. It is also possible that others could join this DAO and contribute their own water rights or sources of water to be managed collectively. This would depend on the specified terms and rules established by the DAO. This has the potential to become a new form of utility.

JYG:

I also, by the way, love the term “A new utility.” The idea of designing caring infrastructures that are in support of very specific spaces in the city is just an incredible project.

I know you trained as an architect, and now you work, not as an architect, but within systems and scales that are approximate to what would be required of building and spatial practices. Does architectural knowledge propel you in some way? And do you have advice for young architects who might be seeking to engage in alternate ways of practicing?

LB:

Architecture needs to consider its carbon imprint. It’s the second-largest propagator of global warming, after the military-industrial complex. A fundamental question for me was, “How does architecture fit my desire to do reparation work?” I didn’t see any way through that, other than to set out to do environmental work with an architectural degree. Sometimes the best thing is not to build, but rather to unbuild, un-develop, to think systematically about how to negotiate when the best thing to do is to repair rather than to complicate.

I didn’t find then, and I’m not finding now, much real discussion in architecture about un-structuring the discipline around the place we’re at culturally, which is end-game capitalism. It’s hard to unwind capitalism from architecture. Whereas in art school and art discourse, a lot of artists are quite committed to lowering their carbon imprint in their exhibition strategies, and thinking about the materials they use as being something that’s going to be on the planet after an exhibition. There’s also been a real questioning about who we are working for and who we are working with.

What I would say to young architects studying is this: Think about how one can reframe the discussion with clients, and how we can incentivize not building. How can we make not building, or taking apart what doesn’t serve systems thinking, a part of what we uplift with the professions of architecture and landscape architecture, rather than continue to fetishize the idea of urban form for its own sake?

Jia Yi Gu:

There are some people who are beginning the dialogue around degrowth and disassembly, but pedagogical and academic spaces definitely haven’t caught up.

I’m teaching a course at The Alternative Art School, Posthuman Infrastructure, that reevaluates what we make in relation to metabolic cycles and more-than-human entanglements. Some people will say, “Well, what do you think about Frank Gehry’s master plan at the LA River?”2 I think it’s great that his abilities get a lot of people excited. But is it going to happen? How does his plan uplift the efforts so many have been making in recent years to restore and revitalize the Los Angeles River and its natural habitats? How does it articulate the systemic reparation that is needed and the idea of community efforts? How does it uplift native and indigenous voices?

Before the development of the region, the Los Angeles River and its tributaries drained a large, semi-arid watershed of over 2,000 square miles. The system of concrete channels was built to contain the river’s flow and prevent flooding in the city. These changes to the river’s course have had significant impacts on the natural environment. Another city is possible. And Bending the River sees the LA River as key to this effort.

- 1 An eleven-mile stretch along the Los Angeles River that is adjacent to Glendale, Griffith Park, Los Feliz, Atwater Village and Elysian Valley.