relational architectures is a series that locates ways for design to operate through relationships built on solidarity.

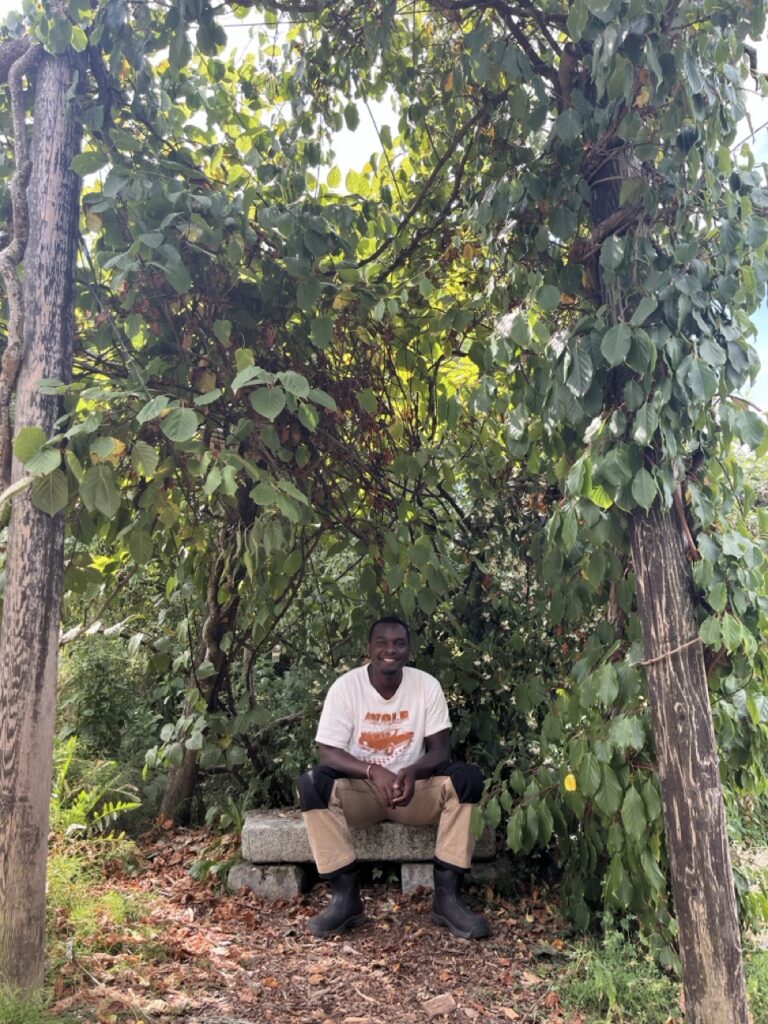

When Khalil Griffith first moved to South Beacon Hill in Seattle, he was working a job he didn’t really care for and he felt a sense of loneliness. “All I had was my house plants and two friends,” he recounted. As he was exploring his new neighborhood in search of something “to get into,” he saw a flyer for a work party at the Beacon Food Forest. That work day happened to be the groundbreaking for a new section of the food forest, the BIPOC Garden, and it was a day of planting fruit trees and bushes. Two years later, the BIPOC Garden and Khalil are flourishing. After volunteering, then joining the board, Khalil is now the site and programs director for the Beacon Food Forest.

The Beacon Food Forest was a seed planted by four students who conceived of the idea as their final project for a 2009 permaculture design course. Anchored by guilds of fruit and nut trees, it is “a woodland ecosystem that you can eat,” explained Glenn Herlihy, co-founder of BFF, who drew up the first plans for the space with fellow student and co-founder Jacqueline Cramer. Walls of berry bushes, mid-sized shrubs, vines, ground cover, and patches of flowers, nitrogen-fixing plants, and edible produce provide nurturing layers in this forest ecology—building soil, storing water and nutrients, and contributing to the web of life that draws pollinators, bunnies, and people to the land. Unlike conventional gardens, food forests are designed to self-perpetuate with multi-species actors.

The Beacon Food Forest sits on a 7-acre slope on the west side of Jefferson Park. Besides Khalil and his colleague Priya Marita Diaz, the community relations director, the operation is entirely volunteer run. After organizing neighbors and wrangling with the city, in 2012 the founding members broke ground on the site—situated on public land owned by the city of Seattle. The site is considered one of the largest contemporary public food forests in North America (others include Atlanta’s Urban Food Forest at Browns Mill, Asheville’s Bountiful Cities network , Portland’s Malden Court Community Orchard, and Tucson’s Village Farm). On a sunny day in July we sat with Khalil to learn more about what it takes to manage a community-stewarded food forest.

LinYee Yuan:

How did you get interested in gardening?

Khalil Griffith:

I didn’t grow up planting, I grew up doing the opposite: cutting grass. My dad has a lawn care business and we were weeding and pulling stuff out of the ground. Then I came here and it was a stark contrast, but a lot of those skills carried over—it’s all living maintenance.

LY:

And what was it about your experience during that first work day that brought you back as a volunteer?

KG:

I felt so affirmed at that first work party. I wasn’t necessarily nervous, but I felt like I needed to be in the back because I thought I didn’t have the knowledge to make decisions. As we were sitting together talking about our prior experience with gardening, the others were like, “dude, you’re good. You have the experience, whether you know it or not—you get it from your ancestors and your family, and we learn from each other.” Immediately after that, I recognized that I did know things: For example, I remember there was a point where we were deciding where to plant a blueberry bush, and I said, “This soil is kind of soggy and it’ll probably kill the bush.” And Priya turned and said, “See, you do know stuff.”

My thoughts were valued and heard, and I knew enough (even if I didn’t know it all). I came back because I felt affirmed and I hadn’t really been in a space like that, especially a green space.

LY:

You’ve sat in lots of different positions within the organization—from a first time volunteer, to a board member, and now being on staff. What advice do you have for people interested in starting a food forest?

KG:

The people are everything, you can’t do it all yourself. The biggest thing that makes the food forest work is the people. You have to trust people. I love the work, but it’s hard and it’s really easy to convince yourself that you have the capacity to do it all. We are a collective and together we help make decisions that bring us all forward.

“The people are everything, you can’t do it all yourself. The biggest thing that makes the food forest work is the people.”

LY:

What does it mean to collectively make decisions?

KG:

For example, we wanted to build a fire pit in the BIPOC Garden. Cherry, one of the people that started the BIPOC Garden, would always be like, “it’s your garden, do whatever you want.” When I first started I didn’t recognize the autonomy that we had in making decisions. Maybe a year and a half after first talking about the fire pit, Renee and I were working on something and I was like, “check these bricks out, they’d be great for a fire pit.” So we moved them around and did our thing. We checked in with everybody, and everybody loved it. That’s a simple version of collective decision making.

It’s having those discussions and really allowing things to unfold. If there’s a situation where somebody is like, “this doesn’t really work,” then we move it. We put some tree stumps around the fire pit for seating and Jesse said, “as a person in a wheelchair, I can’t get in if the logs encircle the fire pit.” So we adjust. It’s a constant thing. We adjust and we figure it out as we go. We do what we can, the decisions come and go. We flow and will eventually get to that point.

LY:

It seems very much like a living organism.

KG:

Absolutely. It baffles me sometimes!

LY:

You’re about to launch into your next phase, the development of the next half-acre on the site. How does something at the scale, which is more about high level planning, unfold on a collective level?

KG:

It’s taken many meetings, work days, and discussions to figure out what’s going to happen on the hillside. Starting out with engaging with the community, we ask, “what do you dream of in the food forest? What do you think makes sense? What have you noticed from being at the food forest?” And we got all kinds of responses. Somebody suggested a slide on the hill! We thought about slides and play spaces for kids, aquaponics, all sorts of things. We look at the site, consider what’s doable and not doable based on our parameters. We have more meetings that go more in-depth about certain parts of the planning, and then we decide together what makes sense.

There’s also the aspect of it being a living thing. People come and go, that’s the nature of the food forest. We just do our best to keep it going while honoring the wishes of the people. We think about honor with the development of the land, but also the plants that we grow. We try our best to honor the neighborhood.

LY:

One of the primary differences between a community garden and a food forest is the ecological aspect of it—the layers of plant life, insect life, microbial soil life, and animal life, that are entangled and commune with each other. What are the primary functions that volunteers have to do to maintain the livingness of this place?

KG:

It’s maintained wildly. Three and a half acres is a lot of space. While new things get introduced and entangled, a lot of times we end up letting things do their thing for awhile because there’s a lot of life within each pocket of the food forest. We have some people, like Julie, who work with plants, even when they’re not here. For them, it’s almost a reflex on how to maintain the space. But when there are so many new people coming in, we also do a lot of training.

We do our best to keep an eye on what’s happening in the forest—whether its weeds or plants that are outgrowing their bounds. We make a note of it, and later down the line, we might find something else to do with it. A lot of things, especially “weeds,” we do our best to pass on. There’s a lot of medicinal groups looking for things like mugwort or sticky weed (cleavers). Things like blackberry or willows we’ll cut back and then pass on the branches.

LY:

Switching gears, how do you decide what the bounds of the group are? You have a board of directors, volunteers who self-organize into committees, and then you and Priya are the only staff. Do you track volunteer hours?

“You cannot run the food forest without having the community in mind, and that’s what keeps it going. At the same time, community work is big work. It does not turn off. The people’s problems don’t turn off. The problems of the world don’t turn off. You see a lot. This is frontline work.”

KG:

The food forest is too big and too dynamic for us to set hours. There isn’t a true hierarchy because we practice through sociocracy. A lot of decisions, even within the board, are made through consensus. Everyone’s a volunteer, which is challenging. People move away. People have kids. People have so much happening in their lives. We have to go off of who’s available, who’s here right now, who can help us make this happen. And then if we feel like this is something that needs to be pushed to more people, then that’s a moment where we’re like, okay, let’s try and see what the folks in the background think right now.

So many people glorify and look up to the food forest because it’s mostly volunteer organized, which is beautiful, and I think it’s very empowering for many people. The biggest part of it is that it is community powered. It’s community oriented. You cannot run the food forest without having the community in mind, and that’s what keeps it going. At the same time, community work is big work. It does not turn off. The people’s problems don’t turn off. The problems of the world don’t turn off. You see a lot. This is frontline work.

LY:

The food forest is now 12 years old. How has it shifted to fit the shape of what is needed now?

KG:

It’s constantly changing. Everything’s what I call a “duct tape situation”—duct tape and stick, make it fit, shape it to the mold. Everything makes sense within the moment of doing it, whether it’s how we communicate via email or transitioning into Slack communication or the connections that we have that change over time. Everything’s always changing.

We adapt, of course. We are great at adapting, if we do nothing else. We learn better ways to engage with conflict. Conflict is unavoidable in the food forest, unavoidable in life and community work. People carry a lot and they carry it with them every day. When you come into a place like this, you’re bound to share that hurt. You’re bound to display that frustration, or whatever you have going on in your life. You have to interact with it to be able to move forward.

LY:

You’re also an artist. How has your creative practice prepared you for this very multi-tentacled role?

KG:

Conveying ideas, wanting to share what I’m feeling, wanting to get people to understand—and doing that appropriately. There’s a lot of nuance there, and depending on the route you take, your idea might not come across the way you want. I make art that makes people reconsider what they’re thinking or doing. When it comes to translating that into communication, it’s about nonviolent communication. We’re not here to force. We’re here to share and propose new ideas, show people a new perspective.

LY:

Any other tips for those interested in planting a food forest?

KG:

You don’t have to know it all. Somebody else will know it. Just get started, and you’ll figure it out along the way. It’s so easy to get caught up in the thought process and the cycles of wanting to get everything “right.” I’m a perfectionist, or I have been for a major majority of my life, and this job has taught me that you have to know when to call it quits. Sometimes you just have to get the shovel to the dirt, make your mistakes, and figure it out as you go.

LY:

I love this duct-tape theory of stewardship.

“You don’t have to know it all. Somebody else will know it. Just get started, and you’ll figure it out along the way.”

KG:

Another value for the food forest is around spending money. Your inputs are important, but not so important that you have to always approach problems with the mindset of consumption. It’s very easy for us to think, we got to go buy these seeds. We’ve got to go buy stuff to make benches. But, you should allow your mind to run. Allow your imagination to do the thinking for you. In Seattle, you don’t have to buy seeds. There’s a thousand garden shares, a thousand seeds swaps. There’s ways to get free wood chips. There’s ways to get free concrete to make benches or to make retaining walls. There are so many ways to go about building out your dream and you don’t have to do it in a way that’s going to cost you the most. There are ways around everything. Ask your community for help.

You can get involved with the Beacon Food Forest through their weekly Sunset Labs work days or by making a financial contribution to their work.

Read more about edible cities in this piece, Grounds for Transformation, from Issue 6: Design for a New Earth.