relational architectures is a series that locates ways for design to operate through relationships built on solidarity.

On March 7th, 1977, a small group of Latin Americans, most of them from Uruguay, landed in Sweden for the first time. They were all members of the collective Comunidad del Sur and among them were artists, ceramicists, illustrators, and graphic designers. Behind them was years of harassment, persecution, and imprisonment under the Uruguayan dictatorship.

Having made the collective decision to escape persecution, they would seek asylum in Sweden with the help of comrades from the Swedish syndicalist trade union, Amnesty International and others in their international network of activists and comrades. And while they managed to get out of Uruguay, they found themselves in a new, very different country and culture, without housing or income, and facing an uncertain future.

Comunidad was forced to leave behind the life they had built up in Uruguay, but they brought with them their commitment to each other and the ideals of collective living and working. By founding publishing house Nordan, and printer, Tryckop, upon the ideas and ideology that had sustained them back home in Montevideo, Comunidad managed not only to support themselves through a time of political upheaval, but also produced and designed a library of literature in multiple languages as they built new lives for themselves in Sweden.

Comunidad del Sur (roughly “The Southern Community”) was founded in 1955 by a group of mostly students from the art school in Montevideo, Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. The newly formed collective moved into a shared apartment in a poor neighborhood of the eastern part of Montevideo and supported themselves by running a pottery workshop, printing house and by growing their own food. Their lifestyle of both living and working together was influenced by left-libertarian ideas of community-based economics and self-management. Rejecting the nuclear family model, they believed in collective and anti-authorian child rearing, and in giving their children the autonomy to themselves learn collective decision-making. Their ideology, also infused with ecological and feminist ideas, shaped as well the lives they lead as their cultural production.

Laura Prieto was one of the children born into Comunidad del Sur and has been part of the collective all of her life. She was 18 years old when the collective fled to Sweden. ”We were South Americans and we wanted to live in South America.” says Prieto, ”That’s the reason why we first fled to Peru. But the regimes did not allow released activists and political prisoners to move within the continent. They were only allowed to move to Europe, to Spain, to cut their roots. That’s what exiling is about, to break down one’s roots. Break down the people.”

The regimes had managed to sever them from the land on which they had lived and worked, yet Comunidad stayed bound together. Upon their arrival in Sweden the members received help from comrades and volunteers when it came to applying for social benefits, housing arrangements and getting clothes better suited for the Nordic climate. The members of the collective were eventually granted asylum and moved to the Stockholm suburb of Vårberg, where they shared four apartments. Using simple means, Comunidad (now dropping ”del Sur” due to their new geographical circumstances,) took up the printing business again and began publishing a newspaper in Spanish, also called Comunidad. They published six issues a year and distributed it among Latin Americans in exile both in and outside of Sweden.

Not long after, they were introduced to the various left-wing and counter-cultural groups of the time via the network of people which had helped them establish their new life in Stockholm. In the autumn of 1978 there was an occupation of the residential block “Mullvaden” in Stockholm, where the occupiers were trying to stop the municipal housing company from demolishing the old apartment buildings to build new ones. While supporting the occupiers, members of Comunidad were introduced to groups who were running a self-governing cultural center in a former bottle cap factory, who later offered them cheap spaces for rent. ”When we moved in, there was a man who sold us a printing press exactly like the one we had in Uruguay. He sold it for 2 kronor, a symbolic sum,” says Prieto.

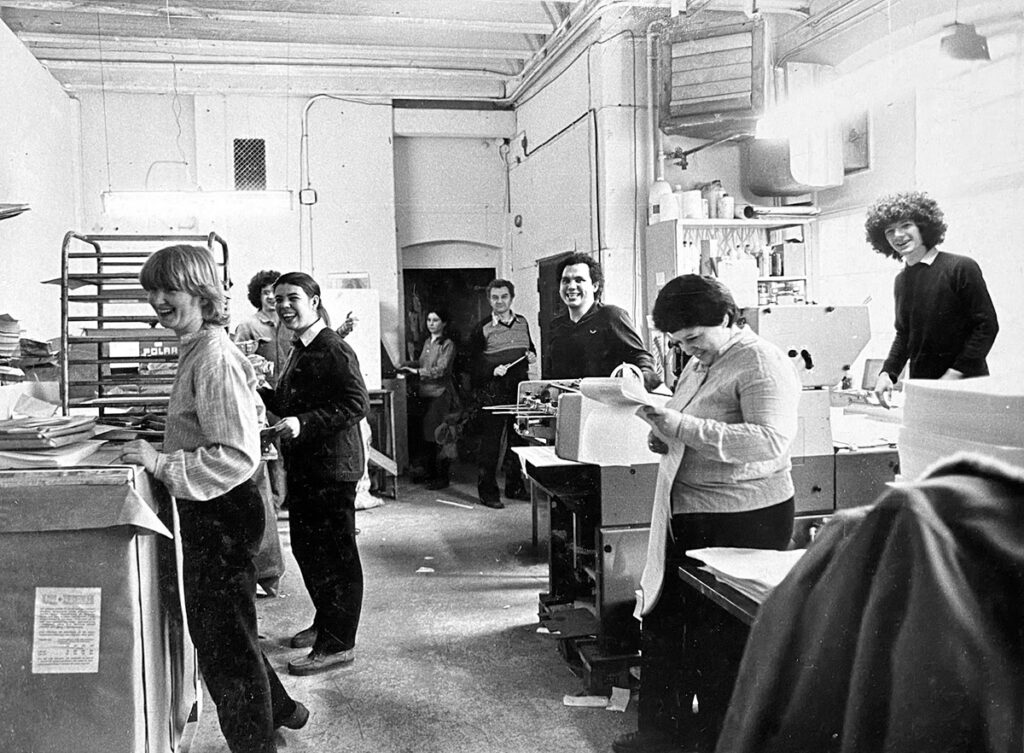

At the same time several members took labor market training courses to build up the necessary skills for running an offset printing press. ”One of the girls, Silvia, had taken a printing course and I had taken one in making printing plates. In Uruguay we had been printing with lead types, but when we came to Sweden this was already an outdated technology, so we had to take courses to learn offset.” While the women of the collective went to printing courses, the men worked at a kindergarten, explains Prieto. ”Upbringing was very important to us. The most important.”

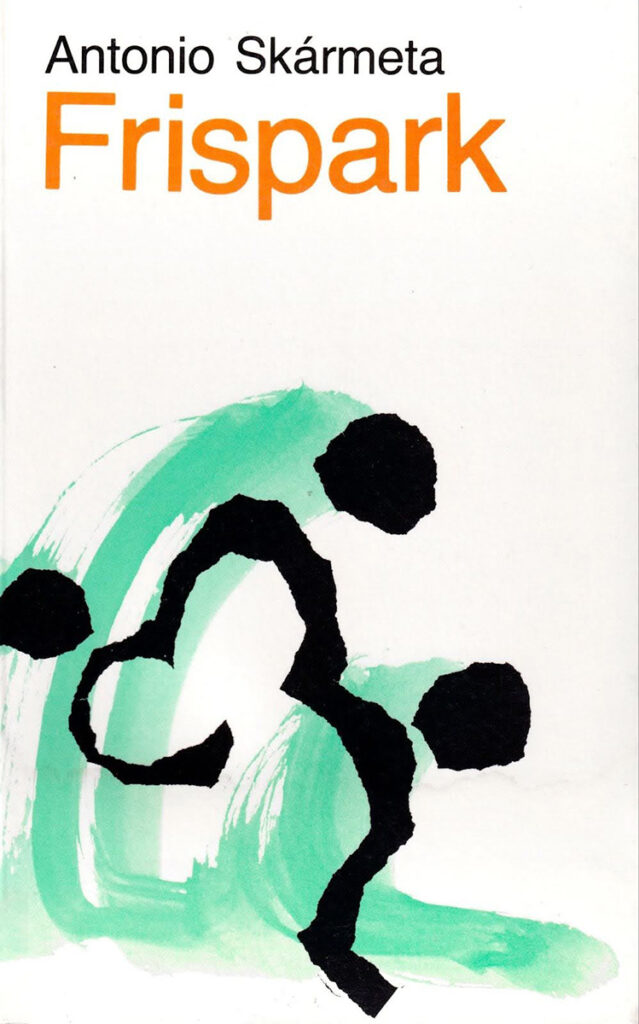

This newly established printing house was renamed Tryckop, (short for “tryckkooperativ,” meaning “printing cooperative”) and in 1980 they founded the companion publishing house, Nordan. ”Since we were based in the north now, we couldn’t call it Comunidad del Sur. So we took the name Nordan inspired by ‘nordanvind’, the Swedish word for northern wind” says Prieto. The ambition with Nordan was to publish children’s books, novels, poetry and political theory in both Swedish and Spanish.

Eventually larger premises in the cultural center, now named “Kapsylen” (“The Bottle Cap,”) became vacant and both the publishing house and the printing house could move in together. ”We applied for a bank loan to start the print shop, which was accepted. We could hardly believe it! Only in Sweden could you get a loan without having to come up with any of your own savings.” says Prieto in an interview published in Frihetens fönster (2023). The loan enabled them to buy more machines, including a larger printing press.

Nordan and Tryckop were not driven by profit motives, unlike ordinary companies. Rather they were set up as cooperatives and economic associations, where the workers themselves both owned and operated the businesses and means of production. There were no bosses nor supervisors and all important decisions were made collectively. Publishers, editors, designers and printers all worked under the same roof and even if certain members had specialized training, there were opportunities to rotate between tasks and to learn from each other.

The two cooperatives became the economic base of the Comunidad collective, but profit margins were small; the members had to save on their expenses and keep personal consumption to a minimum. But every month they received a little pocket money and the collective covered costs for things such as clothing and educational fees. They also cooked and ate their meals together, both in the collective and in Kapsylen’s communal kitchen.”I laugh now because we were such dreamers back then. But it was fun, it was nice. We supported each other,” says Prieto.

In Uruguay, Comunidad had brought together people seeking a communal way of life and continued to do so in Stockholm. The collective grew as new members, Swedes as well as fellow Latin American exiles, joined them. Ana Luisa Valdés, was a teenager when she was imprisoned for several years because of her political activities in Uruguay. Once released, she fled the country and in 1978 received a residence permit in Sweden as a UN refugee. She soon thereafter moved in with Comunidad. “We met in Sweden. We had mutual acquaintances, but I came from a different background,” says Valdés. “I came from the Marxist guerrilla movement Tupamaros and that’s what got me into prison. Comunidad on the other hand were anarchists and actually had a completely different breeding ground for their struggle.”

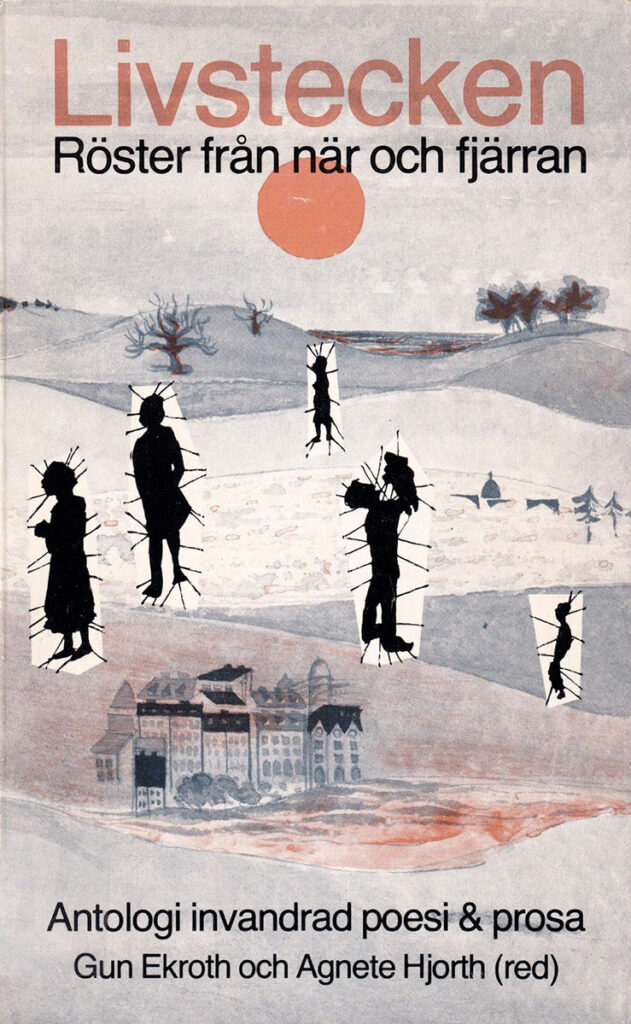

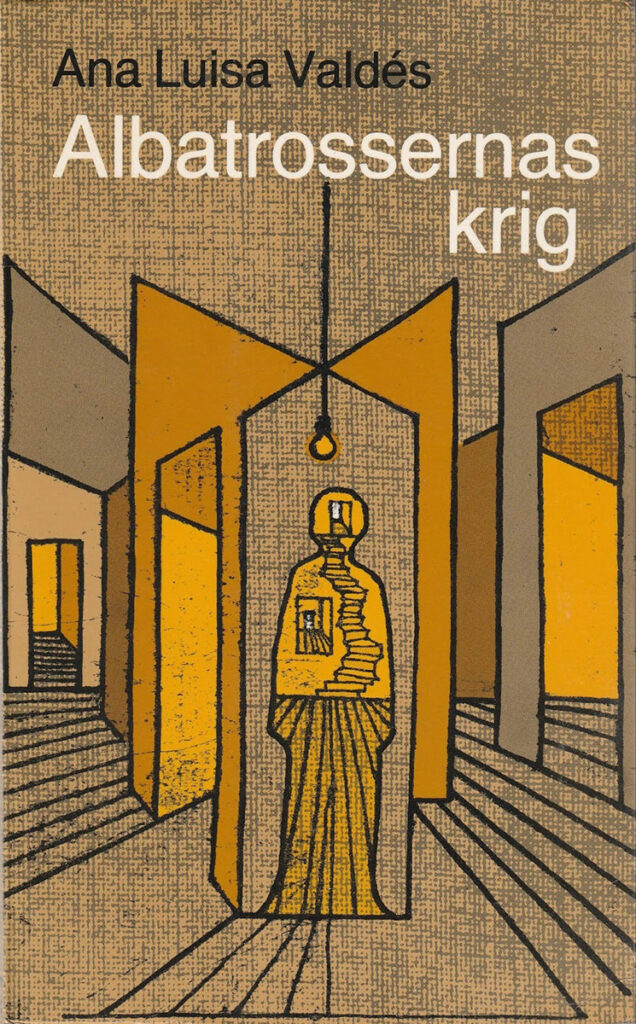

During her time in prison Valdés began constructing what would become the short story Albatrossernas krig (“War of the Albatrosses,”) which would go on to win first prize in a short story competition held in Paris for Latin Americans in exile. She came in contact with Nordan, they were interested in publishing the story and eventually commissioned her to write ten more short stories, which in 1984 were published together in both Swedish and Spanish editions. Valdés would also begin working at Nordan, primarily with finding potential titles to publish. She also translated books from Swedish to Spanish, including novelists and poets Karin Boye and August Strindberg. In collaboration with the Uruguayan author and literary critic Ángel Rama, they selected eminent Latin American works which they translated into Swedish.

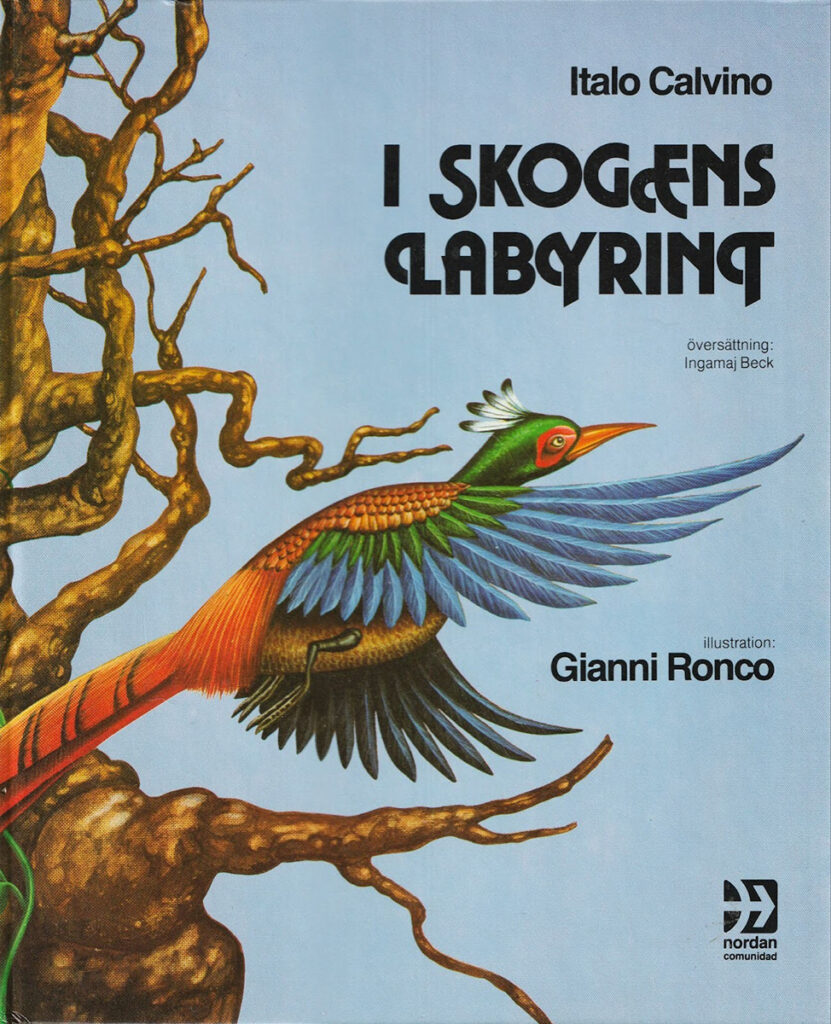

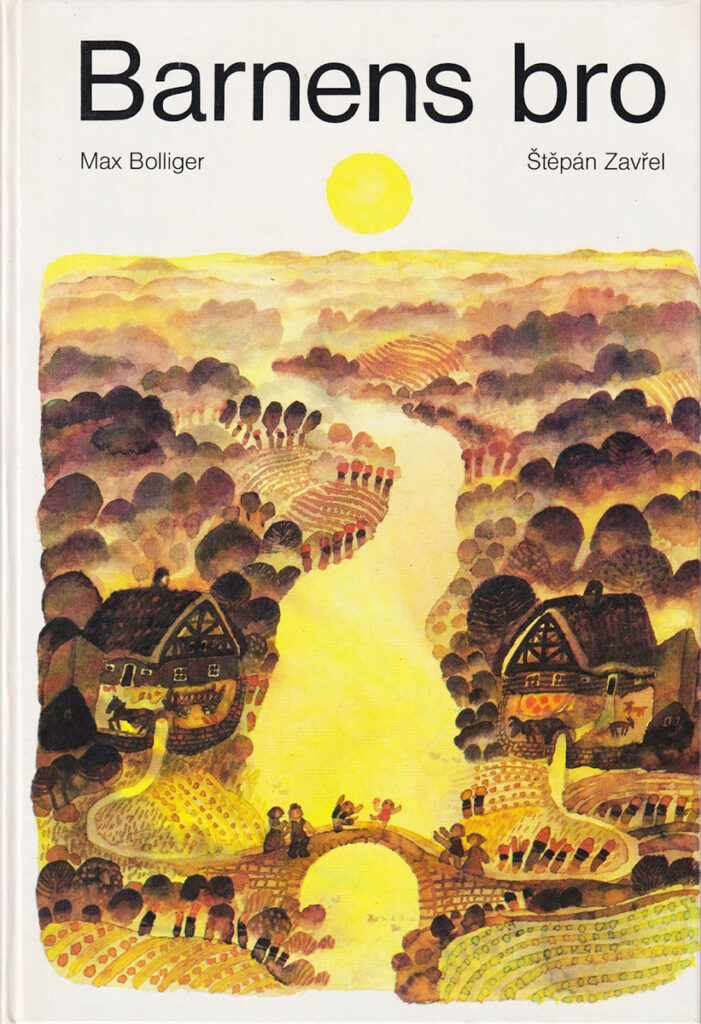

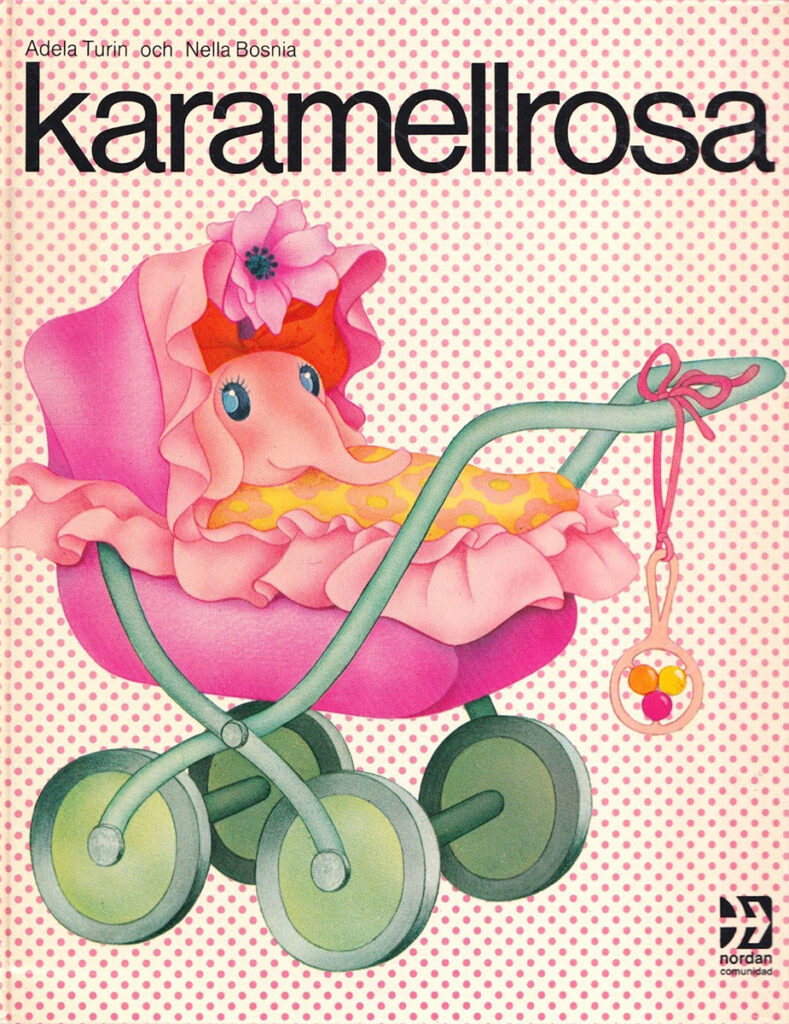

Publishing translations of progressive children’s literature was also a major focus for Nordan, reflecting the importance of child rearing in their collective. One of the first picture books they published was Karamellrosa (“Candy Pink”, 1981) by Adela Turin and Nella Bosnia, a gender-pedagogical story about elephants which was translated into three languages. “We published children’s books in Spanish and Swedish, but also in Finnish since we knew that Finns were the largest immigrant group in Sweden at the time. We wanted to publish alternative children’s books and were looking for books that were feminist, that came from France, Italy, Eastern Europe and so on,” says Valdés.

The publishing house translated many well known Swedish children’s book series into Spanish, among them the Pettson and Findus books by Sven Nordqvist and Gunilla Bergström’s books about Alfons Åberg (Alfie Atkins). ”We brought them to Latin America because we found Spanish-language children’s books to be so dull. They were influenced by the Catholic nuclear family and Disney. They translated almost everything coming out of the USA. So the kids grew up with a very old-fashioned view of the world. That’s why we thought that books like Alfons, which is about a boy living with a single father, were very important,” says Valdés.

These translations from Nordan managed to create a whole new audience for the Swedish children’s books in the Americas. Valdés recounts one experience of the press’s popularity while at a children’s book fair in Mexico: ”I had brought with me books of different titles from Nordan. A man came by and asked how many ’libros’ we had. In Spanish ’libros’ can mean both titles and copies. I thought he meant how many titles we had, so I said ’we have like 14’. When I finally understood that he meant how many copies we had, I said that we had around 3000. ’I’ll buy all of them,’ he replied. The man turned out to be a buyer from the largest children’s book library in Mexico.”

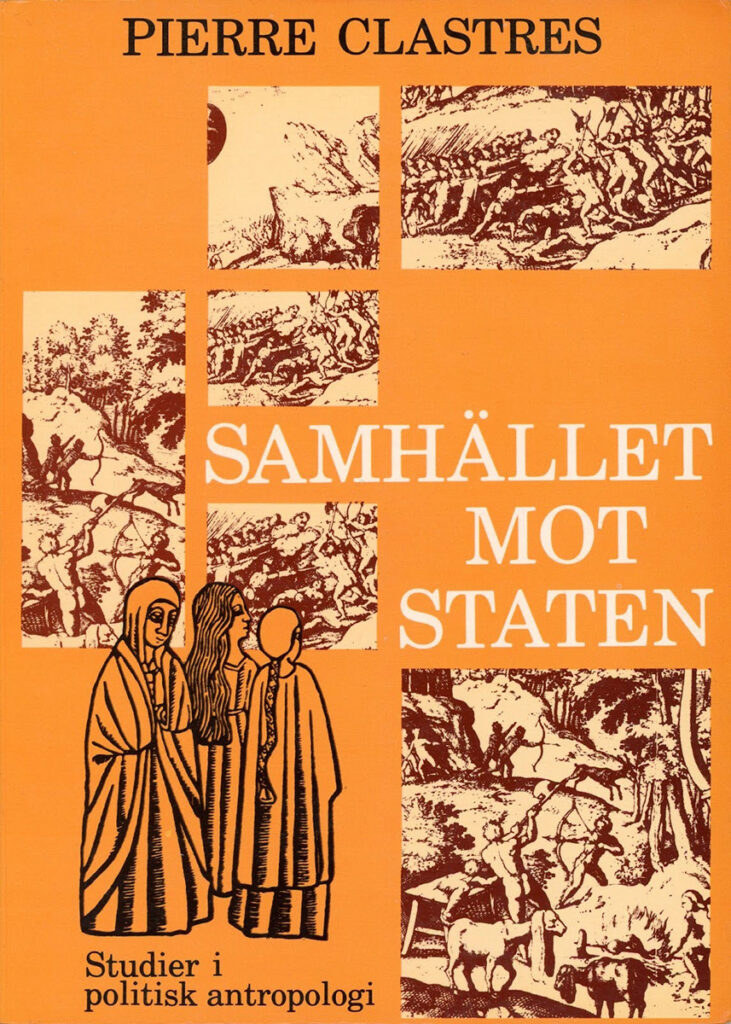

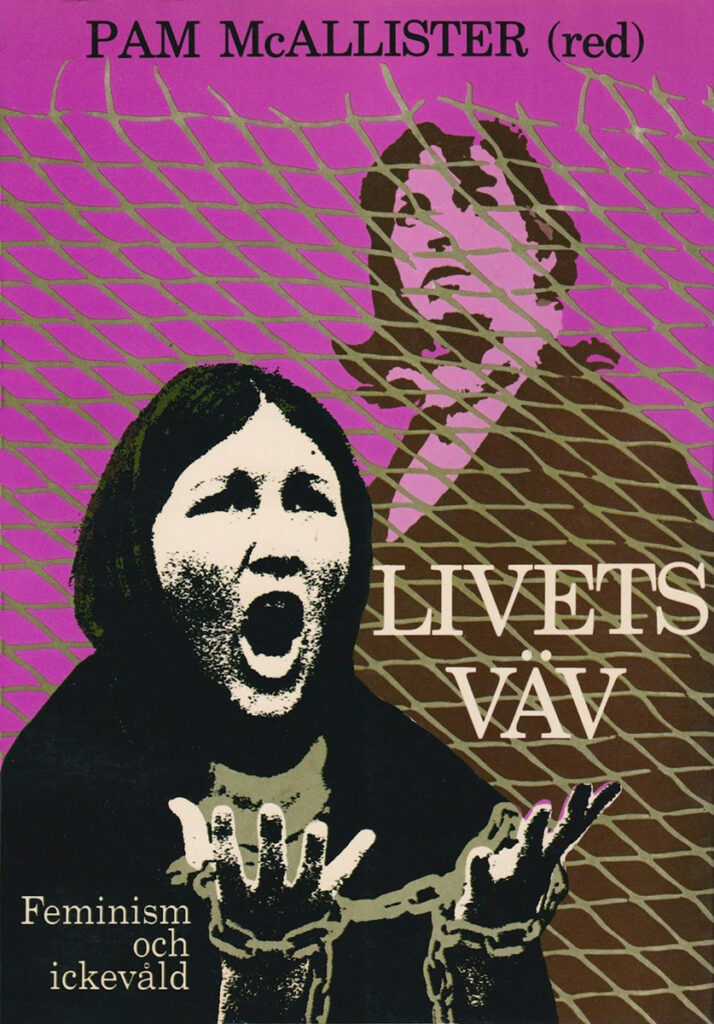

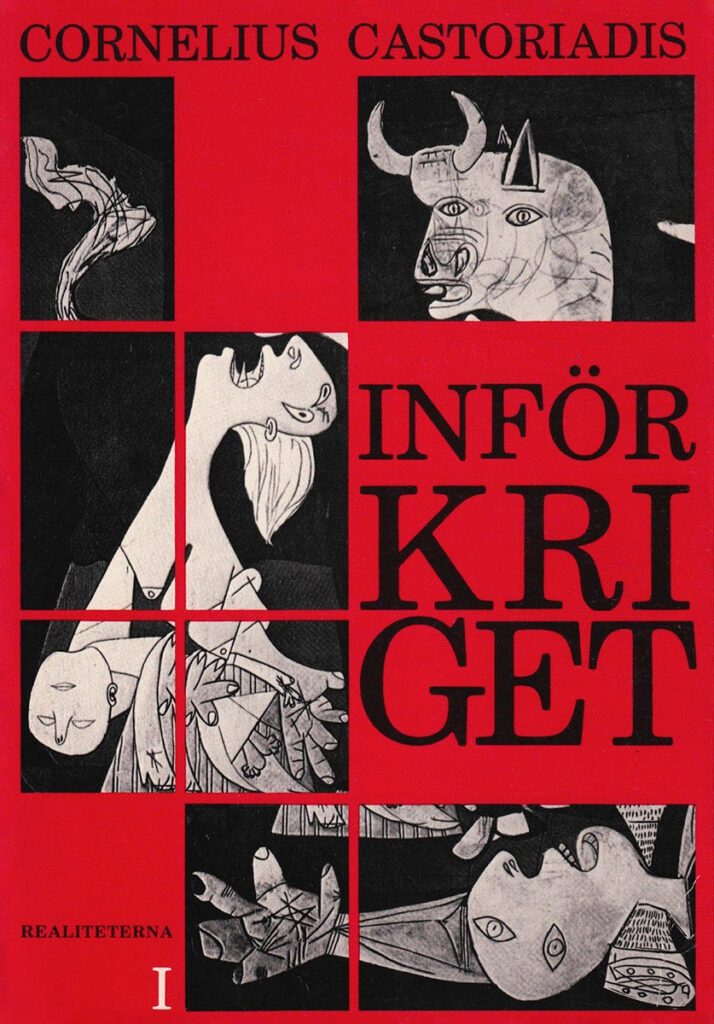

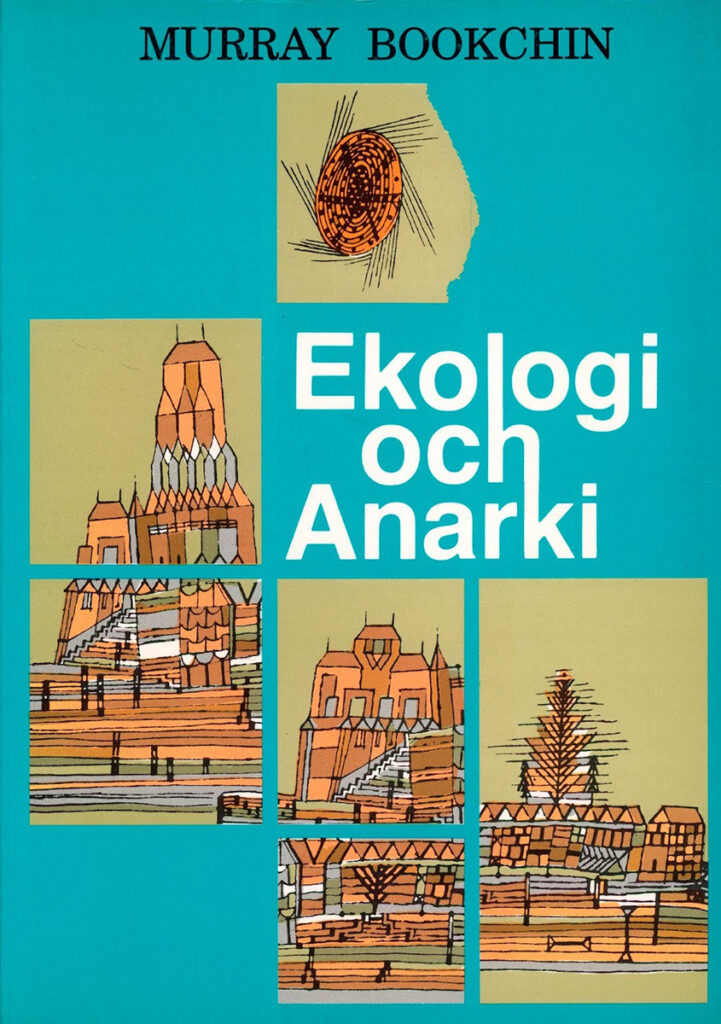

After covering the collective’s expenses, the surplus made from the sales of novels and children’s books was put into the publishing of Nordan’s political theory series Arken. The series consisted of theoretical and ideological works, with the intent of spreading the ideas of libertarian socialism, feminism, and ecology which inspired the collective’s founding and lifestyle. This included essay collections such as Samhället mot staten (“Society Against the State”, 1984) by French anarchist anthropologist and ethnographer Pierre Clastres and Ekologi & Anarki (1983) by American anarchist and social ecologist Murray Bookchin. In collaboration with the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Association they published Livets väv (“Reweaving the Web of Life”,1985,) an American anthology of feminist and pacifist essays.

The series also had its own graphic identity which included a unique spot color per book, titles set in Century Schoolbook, and cover illustrations consisting of deconstructed paintings by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Paul Klee, among others.

“Layout, design and all such things, Ruben was the one who had the main responsibility for that. He loved working with it and we all liked his work,” says Prieto. Ruben Prieto (1930–2008), Laura Prieto’s father, was a librarian and educated in art and architecture. He was one of the collective’s founders and the oldest amongst them. Being a non-hierarchical collective there was no official leader, but Ruben Prieto had a central role when it came to design as well as the group’s ideological direction. “Ruben tried to use what was at hand and while he was working we would sometimes come and move around things on the drawing table. ’Oh, that looks good!’ He’d say–he often managed to involve the rest of us in the process somehow.” says Prieto.

The cover of Tryckop’s printing of Nådatiden (“The Truce”, 1981) by Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti, demonstrates how a cover design could be a collaborative process. ”For example, on the front cover there are a bunch of thumbprints from members of the cooperative and a photo of a woman. I’m the one in the photo that was taken by Bernt, another comrade,” says Laura Prieto.

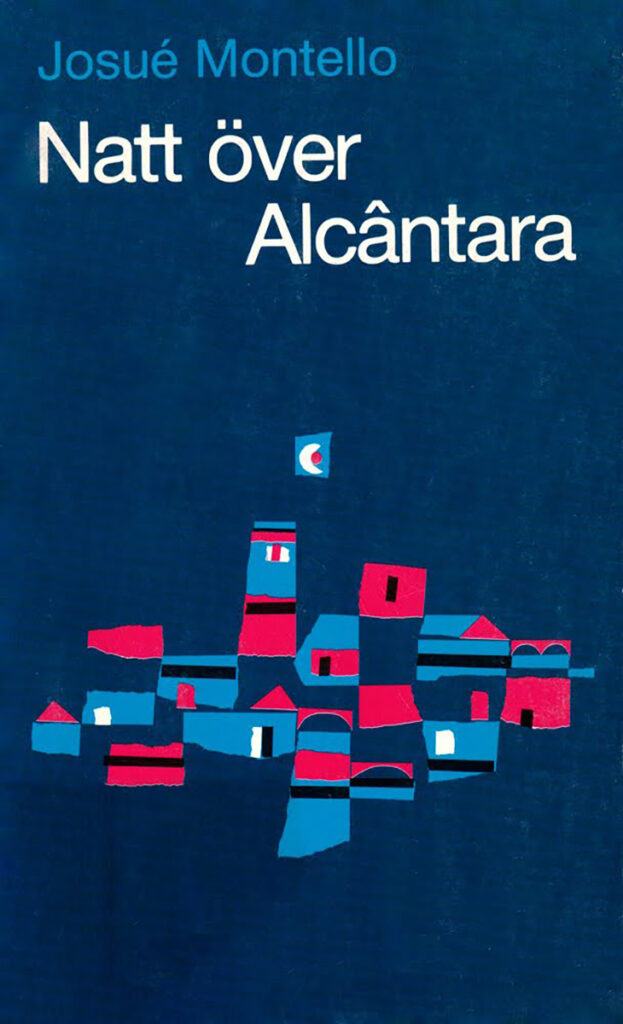

The illustration and design on Nordan’s book covers are characterized by a desire for experimentation and have a rich variety of expression with striking color combinations contrasting with the simple typography, usually set in Helvetica. Many of the covers were made in collaboration with illustrators and artists in the social and political circles around the collective and their cooperatives. The covers created by Ruben Prieto himself often feature torn paper shapes mixed with textures, photos, and illustrations with bold line drawings.

Five years after Nordan’s founding, Uruguay had begun a slow democratization process, initiating the transition from a civic-military dictatorship to a democratically elected government in 1985. After this, members of Comunidad began moving back to resume their collective life and work where it had started. Those who stayed in Sweden sent over money to help with setting up the operations in Uruguay and even some of Tryckop’s machinery was shipped across the Atlantic. ”I remember how they lifted one of the printing presses out of Kapsylen. People outside the building were shocked to see this big machine coming out of the window,” Laura Prieto recalls. A new printing cooperative was started in Montevideo, while the collective moved out to a farm outside the city where they could grow their own food as they had done before their flight to Sweden.

By 1989 the majority of the collective’s members, including most of the core group in Nordan, had gone back to Uruguay. Some of the collective’s children chose to remain in Sweden and continued working in the cooperatives. Tryckop was however soon thereafter transformed into a limited company specializing in prepress production. Nordan continued to release titles sporadically, but not as frequently as before. Ana Valdés stayed in Sweden until 2011: ”The idea was that we would continue with Nordan in both Sweden and Montevideo. But in practice it didn’t work out since we no longer had a print shop.” The Swedish branch of Nordan published its last title in 2007.

Laura Prieto, today working as a home midwife, says that Nordan kept on publishing in Uruguay until 2008 and focused mainly on non-fiction and ideological works. ”The members of the collective here knew how to run the printing business, but after Ruben’s death there was no one left with the knowledge of how to run a publishing house. Nordan exists to this day, but we’re not publishing books anymore.” says Prieto.

In recent decades many Swedish printing companies have either merged, been bought up by larger players or gone bankrupt. Book printing and binding is, to a much larger degree, outsourced to companies in countries with cheaper labor and production costs. The sales of printed books are declining and opportunities for working with the making of books are becoming scarce. With the costs of living constantly rising, it is also increasingly difficult for independent designers and small publishers to make ends meet. But despite these worsened circumstances, perhaps the cooperative model still can offer hope for independent book production.

The London-based printing co-op Calverts, was founded in 1977 and is active to this day. Radix Co-op, founded in 2010 in New York City, is both a printing and a publishing house, just like Nordan and Tryckop. New technologies such as risograph and digital printing have created new and cheaper possibilities for radical print shops like Footprint Workers Co-op. As all businesses, cooperatives have to deal with the competition of the market economy, always making it a challenge to uphold fair and ethical practices. But pooling resources and living more collectively can ease the financial pressures outside of the workplace. Cooperatives that collaborate rather than compete could in the long term potentially build something like solidarity economies.

Nordan and Tryckop were themselves operating in the headwinds of market forces and right-wing ideologies blowing throughout the country. Already in 1976 the Social Democratic Party had lost the general election after having been in power for over forty years. The comprehensive welfare state built during those years, by straddling between capitalism and socialism, would not be impervious to the burgeoning era of neoliberalism. Neither would the popular movements for workers, cooperatives, peace, or environmentalism, of which many lost steam or became co-opted. But despite all this, Ruben Prieto expressed hope for the future in an interview in Boken om Kapsylen (2008). ”I think the time of collective ideals was like a summer, which was over by the middle of the 1980s. It’s now winter and many of us have gone into hibernation. Somehow I recognize this and I know that under the snow are tulip bulbs, which will bloom once the snow melts.”

This essay is a translation from the authors of their original piece for the Swedish magazine “Tecknaren” – Issue 4, 2023