MOLD’s series of Food and Abolition considers how the political, social and economic project of prison abolition, ending the prison industrial complex (PIC) and setting in place reparative networks of care, can inform our movement for redesigning sovereign food systems.

What might it mean for an art gallery to be a site for community care? Against the ongoing tide of gentrifying gallery spaces and art media ringing in the death knell of the art market, Recess, a Brooklyn-based abolitionist art organization, is planting seeds of repair.

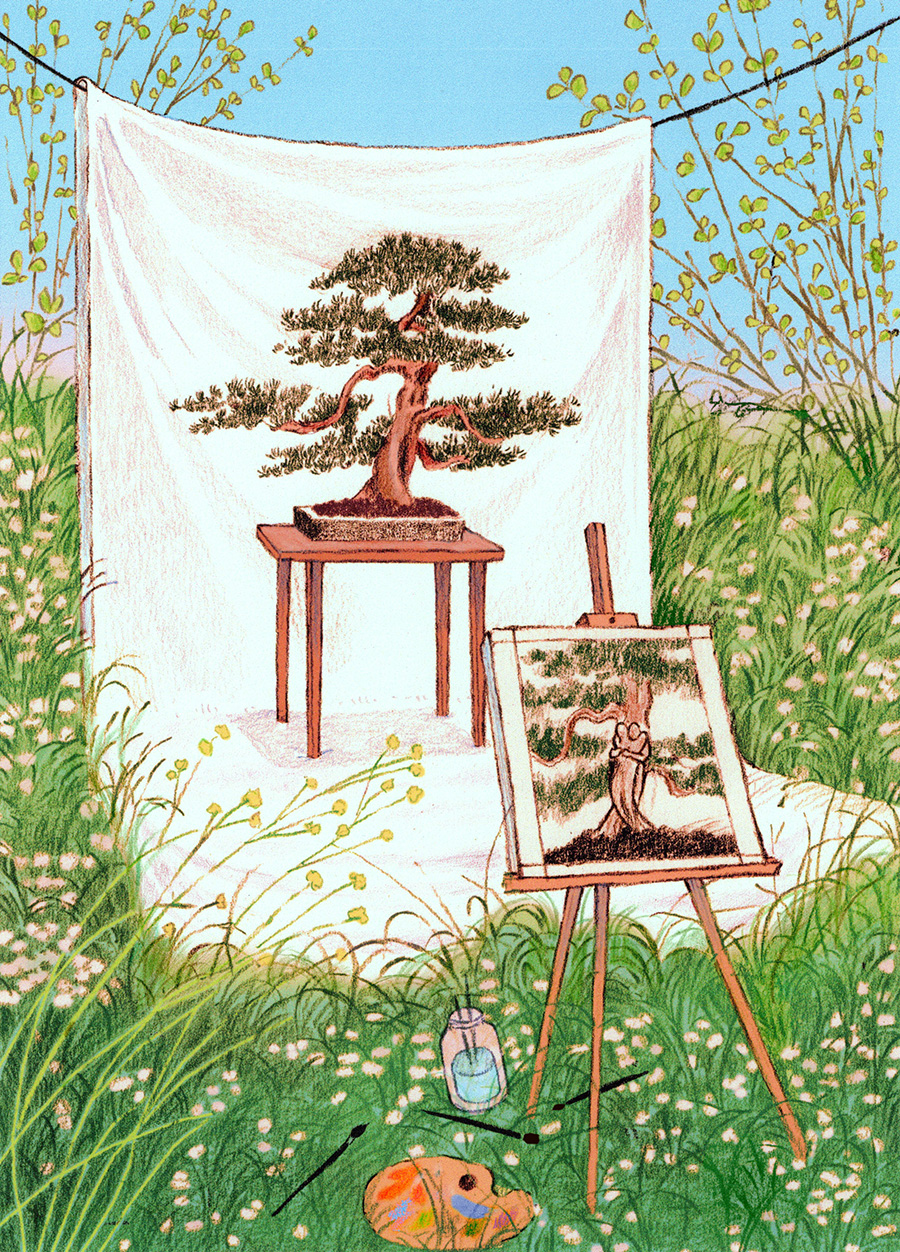

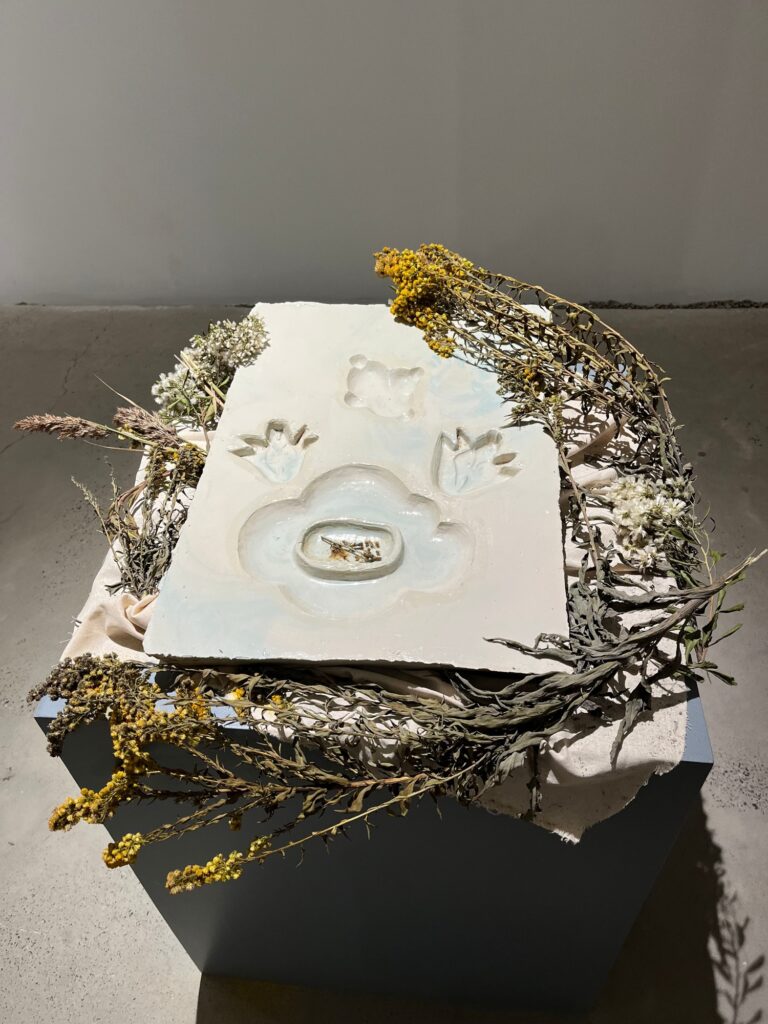

In the early days of the new year I was invited to a community potluck hosted by the artist Marcela Torres and the youth artists of the Assembly, as part of Torres’ session program at Recess. The gathering was a warm affair to rival the chill of the season—artist and chef Zacarias González prepared whole fish encased in clay and wrapped in banana leaf, while guests plated their potluck offerings on vessels designed by Torres and Assembly as part of the artist’s Session residency.

The energy of the room was electric and generous. Guests were invited to eat, experiment with making their own clay sculptures, and engage with Torres and Assembly’s collaborative installation in the space—an mounded altar composed of clay harvested from Denniston Hill in upstate New York. The event was unlike most art events I had attended and it sparked a curiosity about Recess, their structure, and mission.

In 2020, Recess publicly shared their Care & Accountability Framework Towards Abolition, a document years in the making. Since then, the organization, its staff and artists, have been feeling their way towards establishing new models for how to support artists and the larger immediate community beyond the walls of the gallery. I spoke with Recess’ co-directors, Lindsay C. Harris and Shaun Leonardo, and associate director of marketing and communications Alexa Smithwrick about the transformative impact of implementing an abolitionist framework in art practice and administration.

LinYee Yuan: How do you describe Recess as an arts organization?

Shaun Leonardo: We are a platform for artists; in this case using the term artist broadly to be inclusive of our staff, young people and writers, to create an environment in which they are exploring conditions of resilience, safety and creativity, for an intentional community.

Lindsay C. Harris: The process of describing it has changed even over the course of the seven months since I started. Something that came up this week is that I’ll often say it’s a small arts, abolitionist organization collaborating with artists and young folks with care and accountability. And one of the things that someone came back to me with is that abolitionist actually should be first, that it’s an abolitionist arts organization.

And when you say “abolitionist,” what does that mean for the organization?

SL: As a baseline, being abolitionist requires that we work toward—in both internal operations and external programs—the removal of systems that cause harm to anyone that considers themselves part of our community. Simultaneously it is the investment in the imagination and building of networks and ways of being that replace those systems of harm with spaces of belonging and creativity.

Alexa Smithwrick: Our definition reflects years of cumulative realizations at Recess. What is essential to our ethos is that artists are in a unique position to reimagine replacements to systems of harm, not solely their absence.

I find that oftentimes when people encounter abolition as a movement, they stop at the abolishing piece and don’t fully understand that it’s not about leaving a void, but about the reparative layers and systems and networks that come in to replace current carceral or violent systems. The mission of Recess has always been aligned with advancing equity and justice through the arts. Can you share a bit more about the genesis of the Assembly program and how it extends these missions?

SL: My relationship with the organization began in 2016 as an artist and educator. Following the election of Trump, there was an uptick in applications for the Session program by artists who specifically wanted to engage in the subject of mass incarceration and mass criminalization. At the time, I was embedded in a project, with collaborators Sable Elyse Smith and Melanie Crean, working primarily with formerly incarcerated individuals and a few younger individuals enrolled in alternatives to incarceration programs. One of my collaborators put me in touch with Allison [Freedman Weisberg], Recess’s founder and former co-director. It was in the wisdom of the staff at the time to see engagement with the criminal legal system as something that needed to move beyond representation—if the org were to invest in artist projects that wished to enact social change, there needed to be higher stakes involved. In a short matter of time Allison and I were able to sort out the logistical puzzle pieces in developing a partnership with the court system, establishing a connection with Brooklyn Justice Initiatives.

Over the first three years we built relationships with our young people, therefore deepening the stakes. This raised questions for the organization around how we could continuously do this work with more intention. Those questions dramatically changed the DNA of Recess. There was a growing responsibility to the young people that were being brought into the fold, and a lengthening and deepening of those relationships. That really caused those involved in the organization across staff, board and leadership to analyze how we could be serious about abolition as both philosophy and political strategy, in how it could impact all organizational areas. And of course, the experience of the pandemic exacerbated and amplified those questions.

AS: I also want to honor the team members who worked with Recess before 2020 and helped get us to this place. I’ve been in relationship with Recess for years—the first project I experienced was in 2016, I interned in 2017, and I began in this current marketing and communications capacity in 2019. There has been a natural shift in who applies to work at Recess and it is indicative of the way the field is changing. That team shift changed who comes to Recess and who feels safe in our space. It has also changed the questions that folks want Recess to be able to answer.

Shaun Leonardo, co-director of RecessWe are attempting, as an experiment, to think about the organization as a project that shifts and changes with its people, while always carrying intentions of care and accountability.

In 2020, you formally introduced this “Care and Accountability Towards Abolition” framework. Can you talk about the world that you’re imagining and building together, how that looks and feels, and how it has evolved?

LH: I have newer eyes looking at all of this history. As I try to understand by talking to folks, seeing some of these documents and how they have applied, I’m also asking how they currently function, where’s the alignment, and where’s the tensions and conflicts? How can we build on this and continue to move it forward in the future? I came to Recess because we’re at this really critical moment of enacting some of that possibility, of being a leader as an arts organization to actually embody these practices, not just with our young folks and artists, but as staff and board.

How do we think about money and fundraising? How do we think about governance? How do we think about operationalizing some of these key elements beyond the universal salary? There’s not that many nonprofits out there actually pushing those boundaries. We’re all still operating within capitalism and white supremacy. How can you really see what is possible from a place of growth and imagination and not from deficit? To actually think about freedom and what that looks like in concrete terms—within a physical infrastructure of a building, within an entity of an organization as a 501c3—is what I am excited about.

What are the ripple effects within the ecosystem? How does that affect each and every person that comes through this space in whatever type of way? How are we continuing to learn and grow and imagine what freedom looks like? These systems that are ever present are changing who makes up Recess and also which systems are feeling most pertinent for us to grapple with.

Whereas Assembly came out of this process of artistic imagination, there is this tension and sharpening against the grounding realities of living and thriving in a white supremacist system. I feel like this sharpening is the thing that’s going to create the tools of resiliency for the future.

AS: We talk regularly about care alongside accountability and what it means to do this work together while showing up to work in a capitalistic system. If your body isn’t healthy, if your mind isn’t healthy, if you’re holding this lived reality of racism, what does it mean to do this work? For this care and accountability system to work, we had to arrive to a place of shared leadership, which is something that is not only modeled in the co-directorship, but in terms of how we communicate across our staff and how we’re always growing to do that better—looking at transparency and looking at things like the budget for care together.

SL: I would also offer an artistic lens to this. The artist projects model a different set of conditions for existing together. It happens within the micro in each one of our artist projects—there are learnings in each of these instances that impact how the organization can and should act and move. We are attempting, as an experiment, to think about the organization as a project that shifts and changes with its people, while always carrying intentions of care and accountability. In essence asking, how might we move the project of ‘organization’ closer to an artist’s project?

Alexa Smithwick, communications coordinator for RecessWe talk regularly about care alongside accountability and what it means to do this work together while showing up to work in a capitalistic system.

By modeling accountability and care in the way that you hold space for artistic practice, how is Recess influencing the ways that artists are then working and sharing work in the world?

SL: Under the umbrella of this framework, we really center the artist’s wellbeing during their production here at Recess. We think about them holistically, and therefore, our relational work with them begins before the project cycle and extends afterwards. Many of our artists are caught within a vicious production cycle, so the offering of care can actually come as a foreign idea. The impact that we’re trying to make—not only with our community of artists, but as a reverberation in the field—is this reminder that if you are suffering, how could you possibly invest, as an artist, in a sense of community, belonging and wellbeing? We wish to resource this reciprocal fueling of people and process.

LH: The learnings that come through that process have been critical because that care looks very different for every individual. As an organization, we are identifying what resources are going to allow for flexibility and also to hold accountability to a structure that allows for realistic limitations to what an organization could provide. It’s about, “we are invested in you and in this way. Here are the parameters in which we are invested and are wanting to think about your care as an individual beyond this particular engagement,” whether that’s as an artist, a staff member, or an Assembly young person, and being really clear about that. We are continuing to learn what that container and multiple containers can and should look like.

SL: Many of these learnings allow us to workshop our value set with external organizations and partners. That work feels really palpable to me in terms of how we might be impacting the field. The aspirational piece is that our artists are better prepared to enter the art world, but with a better understanding of their own needs, how to articulate those needs, what to demand and what sectors of the art world they don’t wish to participate in.

LH: And we don’t always get it right. As Shaun was saying, it’s an experimental process. There’s many times that we’re fumbling through as we figure this out. The process is never going to be perfect. The process may never be complete. But we continue to learn and be responsible and accountable for each of those moments. That allows us to also push forward to understand where, as an organization, we need to go to really enact these values.