Convivial Cosmogonies is a series that examines culinary labor practices and their material origins.

Recipes act as document, container, process, agenda, care, code, story, knowledge, and technology (see also Mythmaking and Magic in Votive Foods). Recipes slip between uses, or perhaps more accurately they are wielded in service of projects of communication, reshaping, and perpetuation in a range of combinations. In my own life and practice, recipes have provided contour and structure to the often ambiguous distinction between the technical and the sensual in food. While in the studio, the recipe becomes synonymous with process or protocol, in the kitchen they become narrative tools and vessels for larger dynamics at play. My screenshots and handwritten notes of remembered and altered dishes from family members or friends are as instructive as, if not more so than, an edited and internationally published tome of recipes. Their utility is a particular ability to recall the physical and sensual, not so much their ability to be widely interpreted. Essentially, recipes are wielded as tools or “equipment” as defined by Heidegger, who sees the action of using of tools as defining and affirming their very nature: “The less we just stare at the hammer-thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become, and the more unveiledly is it encountered as that which it is—as equipment. The hammering itself uncovers the specific ‘manipulability’ of the hammer. The kind of Being which equipment possesses—in which it manifests itself in its own right—we call ‘readiness-to-hand’”1. As an act of perpetual biological and cultural reproduction, each use of a recipe further creates and then affirms itself.

- 1. Heidegger, Being and Time 15: 98

Recipes, unlike a hammer, implicate a tricky tangle of relations in order to make themselves useful. Iin one way or another, they tell you how to produce something. Depending on their source(s), they can act as a document of a process or they can be speculative and share an invented and untested process. In some measure, each recipe is accompanied with an intention — a delicious dish one might want to share with a loved one, or the preservation of a food held dear to a community. It is, therefore, not so cynical to question the source and to look to the form of the recipe itself to decode its agenda. Paying close attention to language, grammar, sequence, ingredients, tools, heat source, and so on will tell you far more than the recipe creator might be willing to disclose. In its essential form, the recipe embodies collective food knowledge and represents a type of reproductive (and re-productive) labor with the potential to sustain or extract from a worker depending on who holds that knowledge. By charting the transformation of recipe forms and their respective intentions, one might be able to trace the threads of neoliberal globalization, capitalism, and the foodways that influence them.

Generally speaking, the contemporary recipe format one might find in a western cookbook or publication is a recent invention. Before its advent, a recipe in its broadest sense was a document of a process that involved some ingestible, and hopefully metabolizable, product. Ingestible rather than edible only because the recipe form owes a great deal to medicine and its adoption of a more formulaic structure and directly points to the close relationship between practices of healing and feeding. Many early recipes blurred the lines between the fields of healing, cooking and spirituality in equal measure and may indeed have more in common with a contemporary self-published diet book or blog than the narrative coffee table tomes that appropriate the title of cookbook. Galen, for instance, in the second century CE recounts several recipes against blood loss that include red coral. Anthimus, a Byzantine Physician in the 5th Century, wrote a great deal about healing and dietetics in De Observatione Ciborum. The food laws in Leviticus instance live between story, warning, and recipe with a range of laws regarding what animals to eat or not and also included a rudimentary recipe for bread: “And you shall take fine flour and bake twelve cakes with it. Two-tenths of an ephah shall be in each cake.” (Leviticus 24:5)

What is most dangerous in appropriation of recipes or ingredients is not the neoliberal concern that the wrong person is profiting, rather it is the concerning increase of recipes adapted and sold back to us as commodity, entertainment, or “content” while disguising the exploited labor inherent to contemporary food production.

Archestratus is another example of ancient literature that provides great insight into food culture and production of his time. Archestratus was a Greek poet by way of Gela, Sicily whose wrote the humorous didactic poem Hedypatheia (“Life of Luxury”), fragments of which serve as a sort of a playful guide to mediterranean food at the time, providing an overview of regional breads and fish dishes. One fragment about “aulopias”, a kind of tuna, even includes the added context of when in the year to make this dish (summer). The equivalent of a note in a modern recipe for a tomato salad that says something along the lines of: “best when made with summer tomatoes”.

A survey of the history of Italian recipe creation and its formats demonstrate how form and function serve as extensions of political and ideological convictions. Archestratus’s efficient almost narrative style of recipe without an ingredient section or measurements was more or less the norm well into the 20th century. Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 book, La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene or Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, was written in a much more earnest attempt to document and proliferate what he saw as “traditional” Italian home recipes. These recipes toggle between a recipe format a cook in 2022 might recognize and the more narrative loose approach of Archestratus. Artusi himself was not a chef, rather he was a politically motivated gourmand who saw cuisine’s potential as a unifying force in Italy at a time when the country had just undergone unification but was finding existing cultural, linguistic, and class differentiation to be an obstacle to a unified Italian culture. This format of indexing existing home and traditional recipes continued in Italy with Il cucchiaio d’argento or The Silver Spoon originally published in 1950 by architecture magazine Domus. A clear heir to this methodology can be found in contemporary projects like Pasta Grannies which began as a YouTube channel and faithfully documents individuals and their recipes in all of their individual nuance.

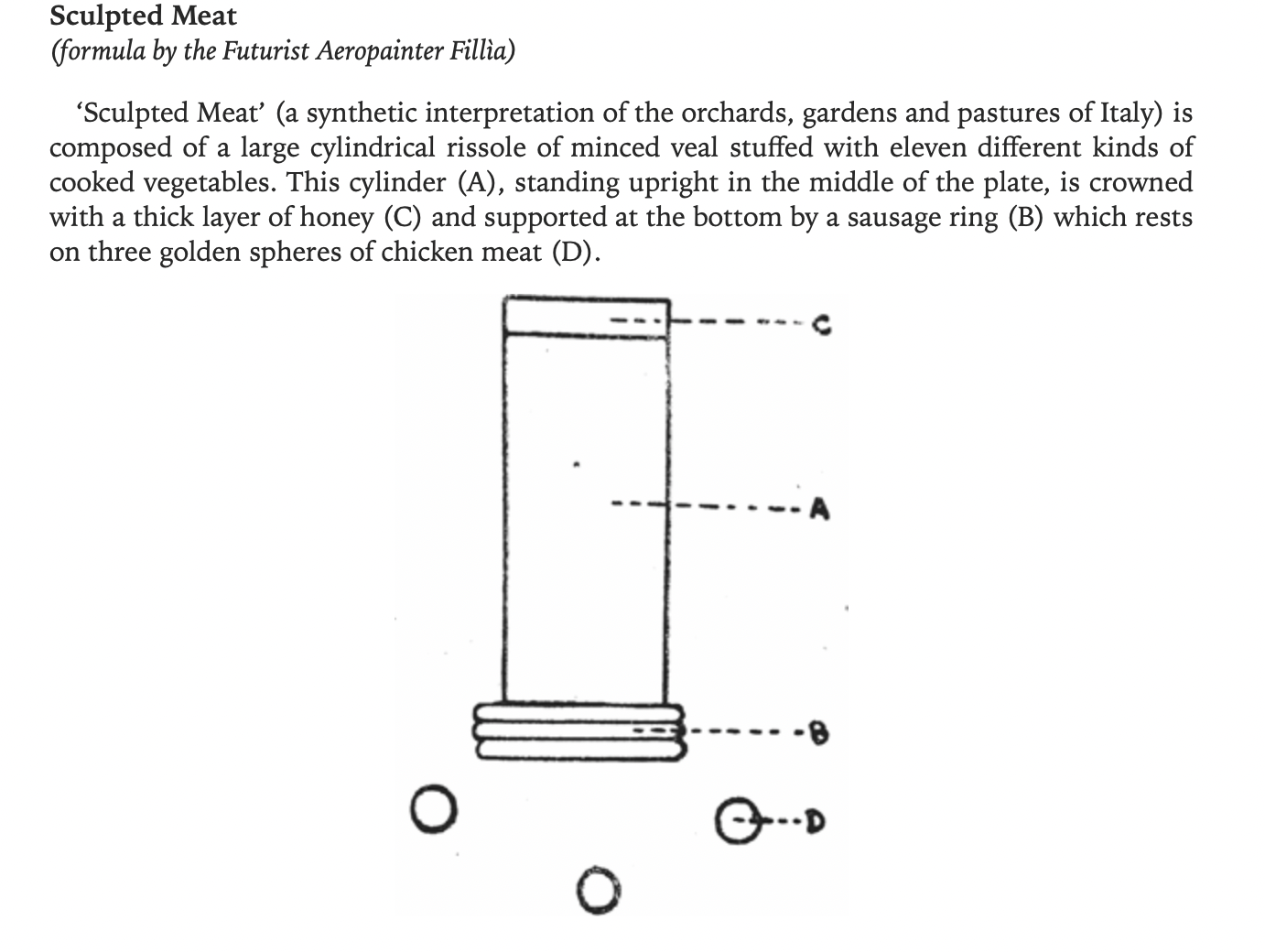

In 1932 members of the Futurism movement Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Fillia would (in a broader collaboration with Mussolini’s fascist project) write and publish the Manifesto della cucina futurista or Manifesto of Futurist Cooking followed by The Futurist Cookbook or La Cucina Futurista. In the manifesto Marinetti explicitly aligns the Futurist and Fascist projects in his controversial call for “The abolition of pastasciutta [pasta], an absurd Italian gastronomic religion.” Describing it in terms of nutritional heaviness as well as its cultural baggage, he says “[t]he defenders of pasta are shackled by its ball and chain like convicted lifers or carry its ruins in their stomachs like archaeologists. And remember too that the abolition of pasta will free Italy from expensive foreign wheat and promote the Italian rice industry.” They gave themselves away here. It was not the pasta itself that presented a problem, but rather the importing of foreign ingredients in addition to the complicated and specific regional traditions and ties maintained by the dish, ones which presented considerable obstacles to the fascist vision of a “unified” Italy. The first Futurist Dinner menu consisted of such dishes as Intuitive Antipasto, Sunshine Soup, Aerofood (tactile, with sounds and smells), Ultravirile, Sculpted Meat, Edible Landscape, and Elasticake. On its face, The Futurist Cookbook itself is not dissimilar from so-called “molecular gastronomy”, though the nominal fathers of the style Ferran Adria and Heston Blumenthal have famously rejected the idea, insisting that their cooking in fact values and perpetuates tradition. Indeed the fundamental difference between the Futurist vision of cookery and that of Adria or Blumental is one of reach: The Futurist Cookbook presented a cookery praxis to replace existing cookery in the general population, while the rarified world of fine dining is more interested in maintaining its separation or, at its most big-headed, assumes a kind of beneficial trickle down effect through collaboration with corporate industrial food through appropriation of its technology. Also included in the Futurist Cookbook is a call for nutrition in pill or powder form, bringing to mind not so much Adria or Blumenthal as Roald Dahl’s Willy Wonka and his magic gum: “when I start selling this gum in the shops it will change everything! It will be the end of all kitchens and all cooking! There will be no more shopping to do! No more buying of meat and groceries! There’ll be no knives and forks at mealtimes! No plates! No washing up! No rubbish! No mess! Just a little strip of Wonka’s magic chewing-gum – and that’s all you’ll ever need at breakfast, lunch, and supper! This piece of gum I’ve just made happens to be tomato soup, roast beef, and blueberry pie, but you can have almost anything you want!” (Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory). The promises of Marinatti and Wonka collectively share the language and promises of revolutionary diets marketed to the public beginning (arguably) with the commercialization of recipes. A diet menu in a magazine, a “clean” eating cookbook, or a “high raw” vegan TikTok also make sweeping declarations promising the audience a way to transcend the messy entanglements that eating and most importantly, cooking, represent.

Recipes are among the clearest representations of nature and labor, a shorthand for interrelated ecological and material realities. Even the most commercial or simple recipes tell a story of contamination, conquest, interpolation, cultivation, and exchange.The inclusion of “All purpose flour” alone encapsulates a many thousand year relationship between humans and a formerly wild grass. Recipes represent a cultural commons; a material practice that implicates natural ecologies and ecologies of labor at every stage of human society. Framing recipes as sites for commoning allows us to assess them as technological marvels in their own right while also speculating as to how they might serve the largest number of people, the landscape, and any other number of species. Within the tangle of cultural and natural elements in any given recipe lies the question of origin (or bad faith arguments about credit). Of course there are massive differences between a recipe handed down through generations, a scalable recipe used in a bakery, and a link to a recipe from the New York Times. Rather than lashing out at a specific recipe or cook that adopts an ingredient or technique without or outside of their cultural context, it is of greater value to look at the recipe in all its faults and discern exactly what the agenda of the creator is. While the use of an ingredient traditional to another cuisine without context might be questionable (ex: rebranding Haldi Doodh as a Golden Milk Latte), what it actually reveals is an ongoing degradation and commodification of a food commons. Arguments about siloing of food cultures is inherently a cat’s paw, food is not static or linear and treating it as such reifies and reinforces its degradation rather than allowing it to be adapted to better serve the majority. Food is by its very nature an outcome of contamination, cultivation, exploitation, and exchange. Any food (i.e both specific food products as well as actual cuisines) enjoyed in the global north come at the expense of those in the global south and as climate change worsens this antagonistic relationship will become increasingly more extreme. What is most dangerous in appropriation of recipes or ingredients is not the neoliberal concern that the wrong person is profiting, rather it is the concerning increase of recipes adapted and sold back to us as commodity, entertainment, or “content” while disguising the exploited labor inherent to contemporary food production.

Recipe platforms, like a fast food chain restaurant, function in such a way as to sap the earnings of workers through paywalls and advertising while simultaneously disempowering and alienating the worker from their own ability to prepare and share food in all of its challenging and creative nuance. We are encouraged relinquish this commons of knowledge in return for so-called convenience and delegation of labor only to have the knowledge stripped for parts and sold back to us in degraded fragments. This enclosure of the free flowing resource knowledge is not unique to food. Marx describes the same dynamic in the primitive accumulation that facilitated the transition from feudalism to capitalism: “these new freedmen became sellers of themselves only after they had been robbed of all their own means of production and all the guarantees of existence afforded by the old feudal arrangements. And the history of this, their expropriation, is written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire.” (Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1) This ongoing enclosure of and alienation from a collectively built body of knowledge is in direct relation with the changes in and degradation of modalities of ecology and land management and, by extension, every thing and practice implicated therein.

Food is by its very nature an outcome of contamination, cultivation, exploitation, and exchange

Access to recipes (i.e. subsistence or subsistence knowledge) mirrors a broader alienation and estrangement as defined by Marx. It is a useful experiment to compare this loss of a collective food knowledge with primitive accumulation and capitalist momentum and enclosures. Perhaps the loss or enclosing of this knowledge may not be incidental and is in fact calculated and continuously exploited in the way that Silvia Federici argues that primitive accumulation is not unique to the advent of capitalism and in fact its repetition is folded into the imperialist expanding needs of the system. In relating to food, we must be wary of nostalgia as the driving force. There is no going back to a romantic “pre-tech” time that reverses current issues. Rather, how can we consider and implement the findings of a material analysis of the ecological relationships and labor conditions implicated in food? In this analysis there is potential for the recipe to be wielded in such a way as to counteract alienation. We can ask, what does it mean to cultivate solidarity through shared (or by sharing) food knowledge? Recipes and food knowledge proliferation are the final stand against a forced forgetting: even when the mother tongue or language is lost, food remains.

⁙ My Mom’s Pasta Sauce (In Her Own Words) ⁙

Courtesy of Ann Gallo

This recipe, “Red Sauce”, is one that required no writing…just watching and adoring the simplicity. Over the years it has evolved, based on available ingredients and personally, the time it took/takes to make.

If you want to be truly authentic, one must buy a lot of small San Marzano-type tomatoes. Bring a large pot of water to a boil and then blanch the tomatoes. I used a strainer spoon to scoop them out to a sieve placed over a bowl. That way they can cool down before you peel and de-seed. If you prefer, use a clean pair of dish gloves to carefully peel and de-seed each tomato. You may want to put on some music that puts you in the mood for this. It takes time and patience.

If you prefer a quicker method, buy the best canned Marzano tomatoes you can find. They taste lovely as well. Guarantee fresh tomatoes taste better. But only you would know that. Also, fresh tomatoes make a more orange-colored sauce. No idea why.

“Red Sauce” was the family name, I believe. The kids and I just called it that. Btw, “Orange Sauce” would be a gross name.

Break out a large, thick-bottomed pot. Slice up the yummiest onions you can find. I like to use a lot of onions. Almost half tomatoes, half onions, but not quite. Depends on you. Do whatever.

Sauté the onions in a good drizzle of Extra Virgin olive oil. Not too hot a flame…but you know how to sauté. Add 2-3 cloves of crushed garlic (smooshed by a knife’s side). Sale, pepe and watch as the onions become clear and smell amazing.

Just before adding the tomatoes, throw in a good handful of fresh herbs. I always use every herb I can find. My garden has Rosemary, Sage, Timo and Oregano. And, of course, basil (but that is to be added later). Chop all the herbs (except the Basil) and toss into the onions and garlic. When you smell the herbs, you know it’s time to add the tomatoes. A moment of truth!! A satisfying moment.

Turn up the heat a bit, stir the tomatoes, onions, garlic, and fresh herbs. Don’t forget to season it again with sale and pepe. Toss in a heaping tablespoon of sugar (helps to make the tomatoes less acidic…at least that’s what I was taught). And then, tear up a good handful of fresh basil and drop into the pot. Carefully fold the Basil into the mixture. Place a splatter protector thing over the pot so as the sauce starts bubbling you save your hands, arms, stove, and floor from chaos.

If you are using fresh tomatoes, the heat should be hotter than canned. It takes longer for the fresh ones to break down and soften so a hot boil is preferred by the Italian ladies. If using canned, not so hot a flame. I like to set a timer for every 20 minutes to come and check on the sauce. However, trust your nose. If you smell something…burning…maybe…it’s definitely burning and you may want to turn down the temp.

It’s up to you but a good 45 minutes, if not longer…depending on your life, and the sauce is ready for the food mill, or how my mom always called it, a mouli. My mom never made red sauce. Not sure what she used the mouli for, actually…maybe mashed potatoes? No, she used a blender for those… She also was a young mom in Italy so probably had to have a mouli in her kitchen, even if she didn’t use it. I always had jarred red sauce as a kid. Never again.

Alternatively, you can also leave the sauce to sit on the stove for as long as you like before using the food mill. Up to you. Anyway, ladle by ladle the pot contents into a food mill that’s over a bowl or another pot. Put the smooth sauce back into a pot, simmer a tad more and you did it!!

Make plenty so you can freeze some…a very 1960’s thought, eh?

Buon Appetito!

- 1. Heidegger, Being and Time 15: 98