MOLD’s series on Nightlife explores the rhythms, metabolisms and revelations that flourish best in the dark.

Farming in accordance with the moon is perhaps as old as farming itself. As Pliny the Elder, stated in his first century document, Naturalis Historia, the moon “replenishes the earth; when she approaches it, she fills all bodies, while when she recedes, she empties them.” This early concept of the earth’s relationship to the moon has brought forth our more modern systemization of farming in time with the lunar rhythm. Today, this system is called Biodynamics.

Within biodynamic farming, a consciousness of the earth’s position in relation to the moon is tantamount to the act of farming itself. As the moon waxes and wanes, organisms on earth respond and react to this gravitational push and pull. Lunar gravitational pull affects the tides, and of course, other things that are mostly water — us, plants, grapevines, etc. What is more difficult to conceive of are the intricacies of micro and macro forces working in harmony because of these forces, and the potential of humans to orchestrate this harmony. Biodynamic farming attempts to decode such forces, organizing a set of tangible practices for the farmer in order to achieve harmony with the celestial forces governing our planet.

The official definition of biodynamics is, broadly, a system of farming following a lunar calendar which employs a sustainable, holistic approach to agriculture using only organic materials, and which views a farm as a closed and diversified ecosystem.

The term itself was first introduced in June of 1924, by Austrian anthroposophist and spiritual scientist, Rudolph Steiner. During the height of the Industrial Revolution, the widespread mechanization of agricultural practice left many agriculturalists and horticulturalists perplexed about the declining health of their farmlands. One sure culprit was the development of plant fertilizers, which had by then already widely replaced regenerative composting. In the name of faster tilling with less labor, tractors had replaced the slower and more deliberate horse-drawn ploughs. From the fruits to the animals, farmers in the thick of these industrial changes began to notice an overall diminished quality of life on their farms. While this mechanization worked in favor of a booming population, the core concepts of the Industrial Revolution rejected any notion of a symbiotic relationship between a microcosm and macrocosm. Quantity had taken precedence over quality, and many began to notice the devastating effects that industrial methods of farming had on long-term agricultural health.

In direct response to the effects of these industrialized farming methods, and the increased dissatisfaction of farmers in Europe, Rudolph Stein delivered a series of lectures he titled, Spiritual Foundations for the Renewal of Agriculture. In this series, he theorized a plan to build back the holistic health of these farms, stating that:

“Of course, if we tell people that human life is a microcosm which imitates the macrocosm, they may very well reject this as nonsense. With regard to human life, this emancipation from the cosmos is almost total.”

Steiner went on to suggest that if these farmers were to see the restoration of their farmland, they would have to do away with the individualistic notion that we are not part of a greater celestial cosmos. Animals and plants, Steiner said, are “to a great extent, still embedded in and dependent on what is occurring in their earthly surroundings” and therefore provided an excellent lens into the overall health of a farm.

In the present day, the term biodynamics is somewhat malleable, however the core concepts remain. Farming in tandem with the moon acknowledges the moon’s role as a governing force of water on Earth, and also considers the moon as the great cosmic reflector. Following this line of reasoning, all the movements of the stars and planets are considered to be reflected off the moon, onto earth, radiating specific energies that can help or hinder forces of reproduction down to the seed.

Farming in tandem with the moon acknowledges the moon’s role as a governing force of water on Earth, and also considers the moon as the great cosmic reflector

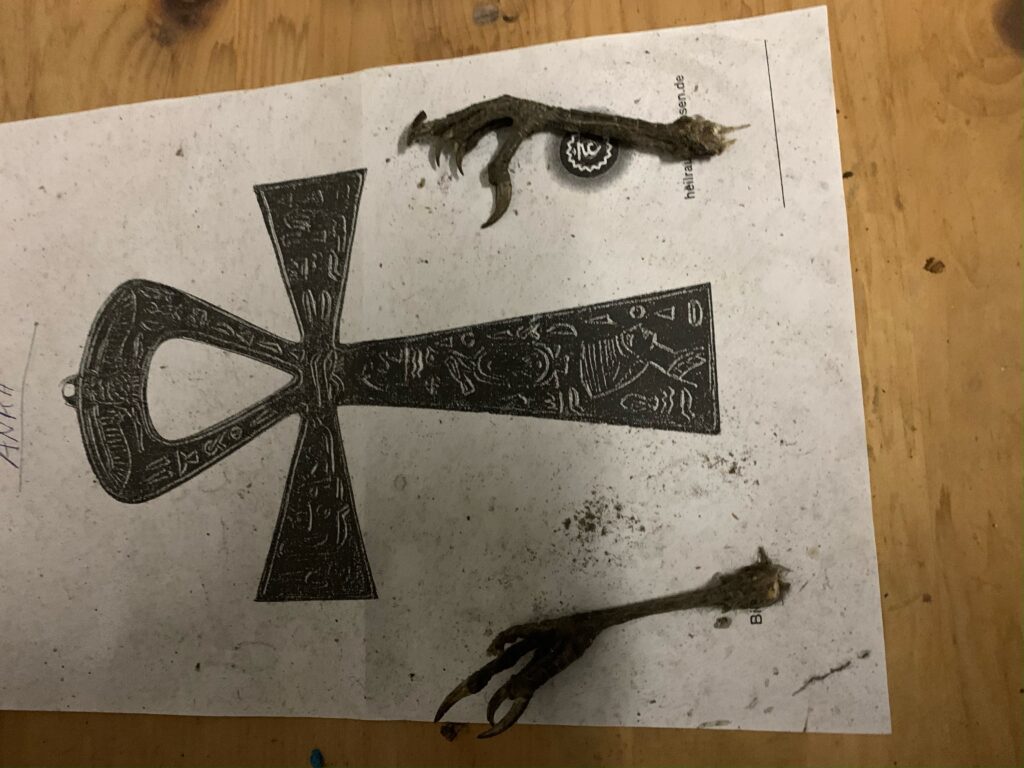

While the concept of biodynamic practice, and the principles surrounding it, can of course be interpreted to represent something occult (consider the practice of wrapping fresh Yarrow blossoms inside of a deer bladder, hanging it dry for the summer, burying it for the winter, and then emerging it as a fertilizer supplement), it is essentially an energy management system — a set of tools, laid out for the vintner, farmer or gardener to use in service of allowing plants, animals and Lunar movements to work in tandem with the human hand.

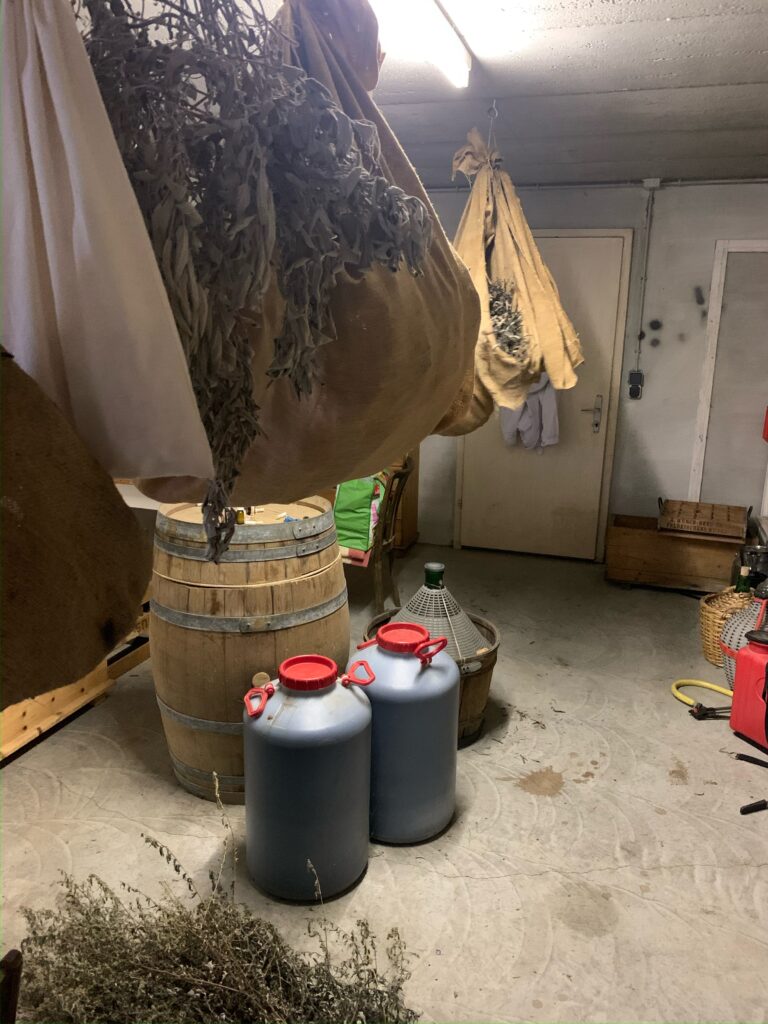

Of the many distinct practices surrounding biodynamic farming, one act in particular is commonly referenced: At the beginning of the winter months, when the Earth is tilted in closer alignment with the moon, a farmer takes a bundle of fresh cow horns, filling each horn with a special compost mixture. That mixture consists of a set of ingredients that include valerian root, stinging nettle, dandelion, chamomile, yarrow and cow’s manure. Once the cow horns have been generously filled with this luminous compost, the farmer buries the horns in the ground, about 40-60 centimeters below the surface, and leaves it there to develop. Six months later, the manure from the cowhorn is emptied, promoting the rapid advancement of seed germination, as well as the increased presence of earthworms.

This specific implementation is widely practiced among farmers and vitners alike, and the reasoning is complex. Within biodynamic theory, the cow (as distinct from the bull or the deer) is considered to have the best temperament for receiving the celestial forces that are said to impart into the manure. As for the choice of the horn, Nicolas Joly describes in his book Biodynamic Wine, Demystified that, “In ancient times the horn was viewed as the source of richness and abundance. [The horn] participates in the connection which the animal has with solar forces of ascension, something one can also see in the ancient Egyptian depictions of the goddess Hathor with the head of a cow and a solar disc situated between her horns.” With this in mind, it is not so difficult to see how the horn, with its crescent moon shape, may hold an astral quality beneficial to the idea of a holistic agronomy.

While many of the mythical (and hyper-specific) practices of biodynamics may sound superstitious to the novice ear, every aspect of biodynamic practice serves a special purpose to the holistic health of a farm. In use, these tools invite specific celestial energy to work in favor of any organisms open to it, allowing for the enhancement of everything – from the nutrients in the soil, to the distinct superior quality of food. This food, even in its most tertiary phase, is theorized to hold greater longevity and purity of expression.

Consider the vineyard, and specifically, wine made from grapes. A vintner practicing biodynamics in their vineyard is working to create biodiversity —from an abundance of bug life present on the ground, to the encouragement of many species of herbs and flowers growing around the vineyard. A wine whose grapes were grown on a biodynamic farm, picked at optimal ripeness (and fermented spontaneously) will likely have more life and a sense of terroir.

Based on a range of factors including soil type and climate, a wine farmed biodynamically may smell like something complex, golden, opulent — like a bushel of fresh peaches at the height of summer — while a wine whose grapes were farmed with fertilizers and chemicals may smell entirely one-dimensional, much like an off season supermarket peach — mealy and boring! Wine is a good example of biodynamics at work, insofar as we can observe something in its fermented stage, which in turn speaks to the quality of grapes at the moment they came off the vine.

Walk into the cellar of any biodynamic vineyard, and you will find a multitude of lunar calendars, biodynamic calendars, various herbal preparations and cow horns, awaiting the proper positioning of the water constellations to be buried for use as fertilizer in the spring. Biodiversity on a vineyard paves a divergent path from the one-dimensional, to multi-dimensional. All this in service of creating a wine that will surely transcend its conventionally farmed counterpart. Biodynamics, however mystical, are an attempt to switch our perspective from individualism to a perspective in touch with nature, and in tune with forces greater than the human hand, creating a symphony for optimal land health, and therefore producing the best possible agricultural products.