The Visuality of Mutuality is a column about the ways graphic design can help support local restaurants, establish deeper roots for food sovereignty, and nourish local food ecologies.

The broadsheet PalatePALETTE, at 11 x 15 inches, is full of images—of Baltimore’s food workers and organizers, of artfully-styled fried chicken, of overflowing tablescapes. Large, expressive display type runs throughout, alongside color-blocked text spreads in pink, lime green, yellow, blue. But for its creator Krystal Mack, the most compelling visual in the publication is a somewhat clinical-looking map opposite the editor’s letter, which shows the city’s “health food priority areas,” also known as food deserts, as determined by the Baltimore City Department of Planning. “It generally comes out every three years, and I always try to pay attention,” Mack says. “What neighborhoods are subjected to food apartheid, and how is it shifting?”

PalatePALETTE presents a slightly altered map, plotting three locations that correspond to the project’s three interviews with people “who’ve sought to abolish food apartheid before, during and after our current state of emergency.” Mack interviews the women of Mera, an immigrant-owned kitchen collective that has served over 100,000 free community meals since the pandemic began, and chefs Catina Smith and Kiah Gibian who facilitate a shared kitchen in support of minority women trying to get their businesses off the ground. She also speaks to Black Yield Institute, a non-profit working toward food sovereignty in the South Baltimore neighborhood of Cherry Hill. In her editor’s letter, Mack notes how each organization has its place in the city’s “local food web,” and throughout the publication I could see glimpses of this webbing, like when the interviewees mentioned their work with, and respect for, each other.

Mack isn’t the first to use the term “food web”1 but reading her editor’s letter for PalatePALETTE was the first time I’d come across it. I was stuck by how well it communicates an idea: that our food systems don’t have to be some faraway, abstract concept. Instead, it can simply be a network of people—your neighbors—whose interdependence on each other provides strength and resiliency. As a whole, PalatePALETTE illustrates this concept nicely, gathering together the people working to feed their community, and making these connections visible in the form of a warm, joyful publication with a hyper-local focus.

- 1. ETC Group. (2017) “Who Will Feed Us? The Industrial Food Chain vs. The Peasant”.

The project is the latest from Mack’s “food-focused social design” studio In Absence Of, which she says she created “quite literally ‘in absence of’ having a space to create outside of traditional restaurant settings.” IAO was founded out of a frustration about the discrimination Mack witnessed and experienced in food spaces as a Black woman. Previously, she had been renting a space in a food hall, where she was the only Black woman-owned and operated business, and left after finding out that the rent she’d been paying for her stall and limited use kitchen was inequitable when compared to White renters with bigger spaces. This was followed by a stint at Little Pearl, an all-day cafe in Southeast in D.C., where she witnessed racism toward colleagues and experienced bias herself, and was let go after bringing it up to HR. “At that point, I was just like, ‘Is there a space for me in hospitality, or the conventional food world?’” she says. Currently run out of her home, Mack started In Absence Of in 2018 with the aim of leading new conversations around food, and the social patterns, cultures and historical structures that surround it.

What neighborhoods are subjected to food apartheid, and how is it shifting?

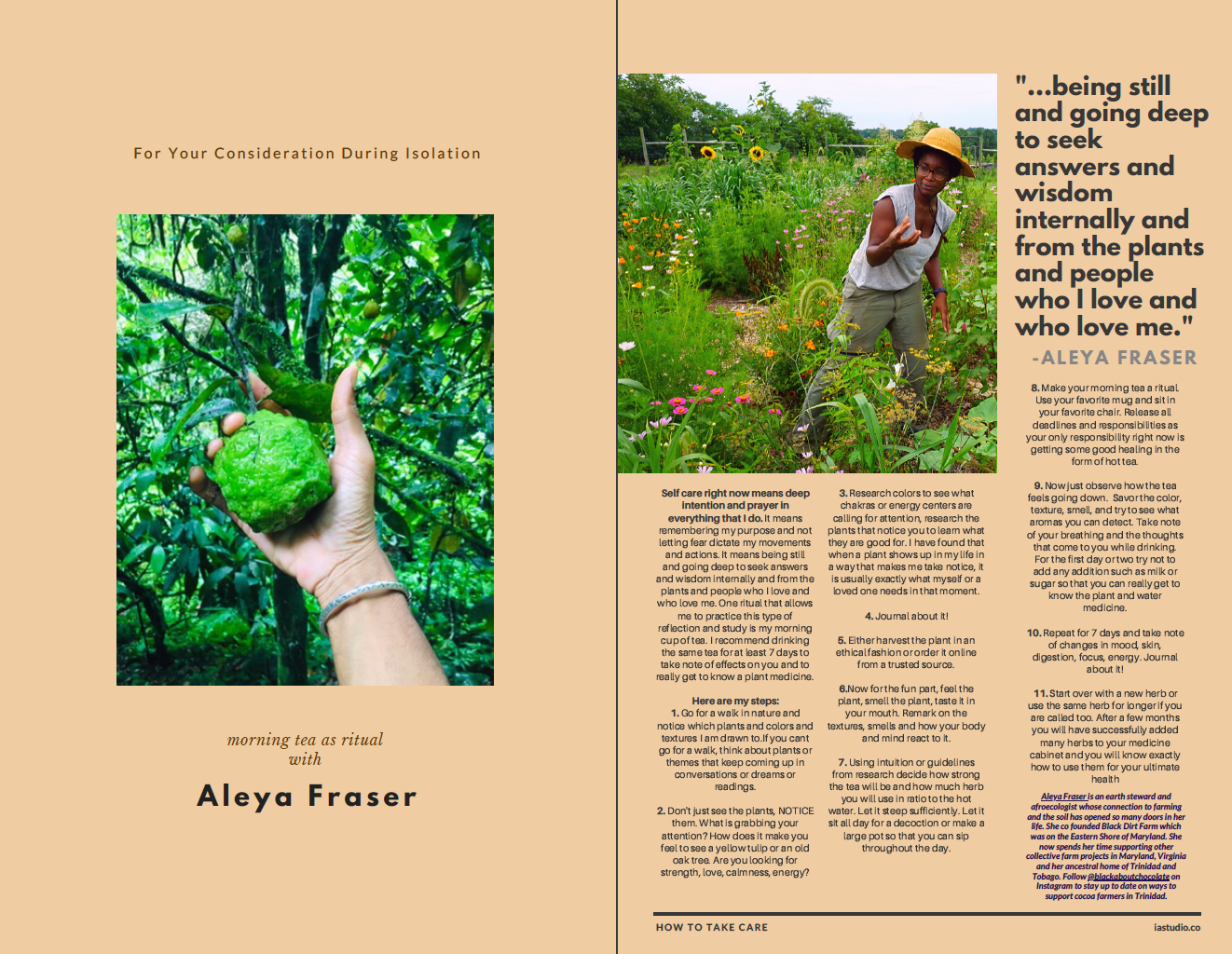

With IAO, Mack wanted the conversations to be accessible, both in terms of actual attendance—low cost or free of charge events at museums, community centers, public parks—and in terms of the content, which she planned to present in a way that was understandable to all and applicable to daily life. “I didn’t go to college, I didn’t go to design school, so I find myself collecting books—on social design, food design, scholarly papers like [Mary Douglas’s] “Deciphering the Meal”—trying to understand and connect with food in a deeper way outside of the patriarchal and capitalist lens of hospitality,” she says. “To me, the mainstream culinary world is very white and male, and it’s unapproachable as far as folks like myself are concerned.” IAO’s projects so far have come in the forms of installations, public talks, and publications. In 2019, she cooked a coal-fired, 18-course dinner called “Clearing the Field” that connected the practice of controlled burning—in which farmers set fire to their fields at the end of a season to clear the land of crop residue—with healing emotional trauma. In fall 2020, Mack held a digital talk with Black Lunch Table and the University of Maryland called “PDS (Plowed. Dumped. Smashed.)” about farmers who were forced to destroy their crops because of COVID-caused disruptions in their supply chains, all while millions of Americans faced unemployment and food insecurity. She did so with a virtual menu that explored the food systems we rely on, and the marginalized workers who keep them running, through the dishes on offer. And in the Spring of 2020, Mack published How to Take Care, her spin on the community cookbook, which gathered together food and drink recipes and guidance for self-care during isolation sourced in the early months of the pandemic.

But one of Mack’s earliest ideas for IAO is one that still hasn’t been fully realized. Her original concept for the first issue of PalatePALETTE was to explore systemic racism and redlining in Baltimore by narrowing in on one meal: the chicken box. The chicken box is typically made up of fried chicken wings; either French fries, chips or bread; and traditionally served with a half-and-half, a drink that’s half-lemonade, half-sweet tea. “It’s a very mid-Atlantic, very Baltimore thing,” says Mack.

Mack wanted to use the chicken box as a device through which to talk about fried chicken’s historical roots in Black American food culture, but also to look at Baltimore’s racial inequities and segregation. When we talk over video call about the Baltimore Planning Department’s map, Mack also tells me about the concept of the “black butterfly,” used by Morgan State University professor Lawrence Brown to illustrate the reality of Baltimore’s hyper-segregated neighborhoods. On Brown’s map, Baltimore’s mostly White neighborhoods accumulate in a coveted strip of real estate running down the center of the city and the city’s majority Black population fans out to the east and the west like butterfly wings. The wings comprise the areas disproportionately affected by food apartheid, toxic pollution, and police brutality, due to over a century of racist policies and practices.

This history puts into context why chicken boxes are most prominent in neighborhoods that make up Brown’s black butterfly, which are also the neighborhoods that have the least access to healthy food options. This makes the chicken box a source of pride and of shame; both a beloved Baltimore foodway and “comestible symbol” of food apartheid, says Mack. “Without a true understanding of food sovereignty, it could create a double bind that places the blame and shame on the oppressed population: You don’t want to draw attention to the fact that aspects of your food culture aren’t healthy, but then you feel like you have no agency to advocate for your neighborhoods and say ‘this is not okay.’”

The beginnings of that project show up throughout the current issue of PalatePALETTE, namely in vibrant, stylized photoshoots of the contents of a chicken box, but Mack put aside the bulk of the idea when the pandemic hit. Instead, she decided to focus on the people who were actively working to strengthen Baltimore’s local food system during the pandemic and imagining new possibilities for abolishing food apartheid afterwards. Mack’s research has made it clear that the city is much more interconnected in spirit than it appears on the map, where initiatives are spread across the city, and that indeed, this food web is tightening. Here, hope in a more accessible and healthier food system lies in the fact that Baltimore’s efforts towards abolishing food apartheid are in dialogue with each other, a community necessary to take on a history of structural racism embedded in the built environment and the food web.

“I didn’t know nor did I plan for the folks that I included in the publication to be so heavily connected to each other,” Mack says. “When I went to interview them, every person brought up someone else, and I was like, ‘that’s the person I’m interviewing next!’ It was so beautiful to me, a little reminder that I was on the right path.”