MOLD’s series of Food and Abolition considers how the political, social and economic project of prison abolition, ending the prison industrial complex (PIC) and setting in place reparative networks of care, can inform our movement for redesigning sovereign food systems. This story was published in collaboration with The Nation.

Below the great expanse of an early morning Missouri sky, razor wire encircles a collection of uniform concrete buildings that cage prisoners. Vegetable gardens sprout up from several places as if to signal their intention to grow over the controlling eye of the accompanying watchtowers. If only. In truth, the vegetables that prisoners produce in these “restorative justice” gardens are part of a carefully choreographed initiative that has always been part of the prison system. In response to public outcry against prison conditions or changing attitudes about the reformative potential of incarceration, prisons have integrated agricultural initiatives to suggest that prison might still be a humanitarian enterprise.

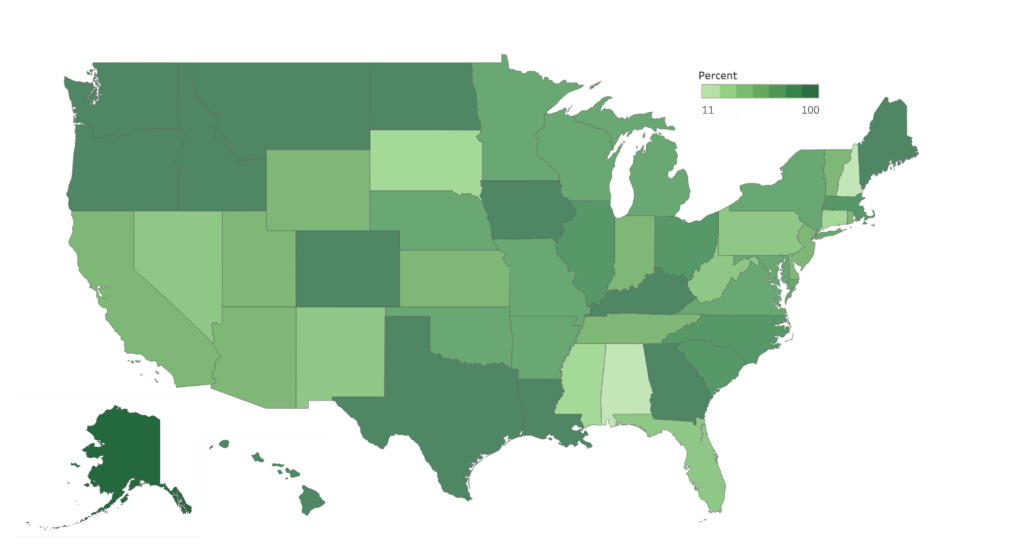

The Missouri Department of Corrections use of gardens is just one example of a nationwide endeavor to use agriculture to gloss over the mass criminalization of poor communities and communities of color. Over 660 adult state-run prisons have agriculture of some kind. From extensive row cropping and ranching to greenhouses and beekeeping, American prisons are deeply committed to agrarian endeavors even as the people they lock up will be unlikely to run their own farms in the future. There are few support networks connecting formerly incarcerated people to agriculture, and even if there were, land ownership is highly concentrated in wealthy and white hands. Prisons incarcerate the crises of racial capitalism: unemployment, poverty, starvation, disease, disinvestment, and dispossession. If prison agriculture restores anything, it’s a commitment to confinement. In the process of turning stolen time into a vast prison industrial complex, proponents of agriculture can lean on the creed of work to justify controlling a mass of abandoned people.

We have been running the Prison Agriculture Lab as a collaborative for over four years to make visible a practice that helped build the prison system and continues to nurture its existence. Our work tells stories through maps, data visualization, multimedia, and more to situate the pervasiveness of prison agriculture within history and place. There is nothing inevitable about where we are today. The violence of incarceration has always been sold to the public in some way. It just so happens that in the United States, working the land is vaulted. It’s God’s work. As such, agriculture is sold as having the power to discipline an underclass—whether with the carrot or stick of hard labor—in need of redemption. But as abolitionists, we do not want to restore the prison plantation. Our aim is to reject and see through the narratives and practices that legitimize incarceration.

Refusal as Generative

As organizers and scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang contend, within the act of a refusal is a “redirection to ideas otherwise unacknowledged or unquestioned.” It is not enough to eliminate prisons and police. Abolition as a desire and a practice builds worlds of care, community, and connection that obviate the need for cages and cops to begin with. The Prison Agriculture Lab has relatedly adopted a set of four principles to create and build together. We offer these principles with concrete examples as a reflection on what it means for us to advance abolition.1

- 1. We advance and explain in more detail our four principles, especially the importance of refusal to abolition methodologies, in a forthcoming peer-reviewed article.

Abolition as Viral

Refuse the gaze on incarcerated people. Instead, shift the gaze to prisons, policing, and the carceral state in ways that spread the urgency for abolition.

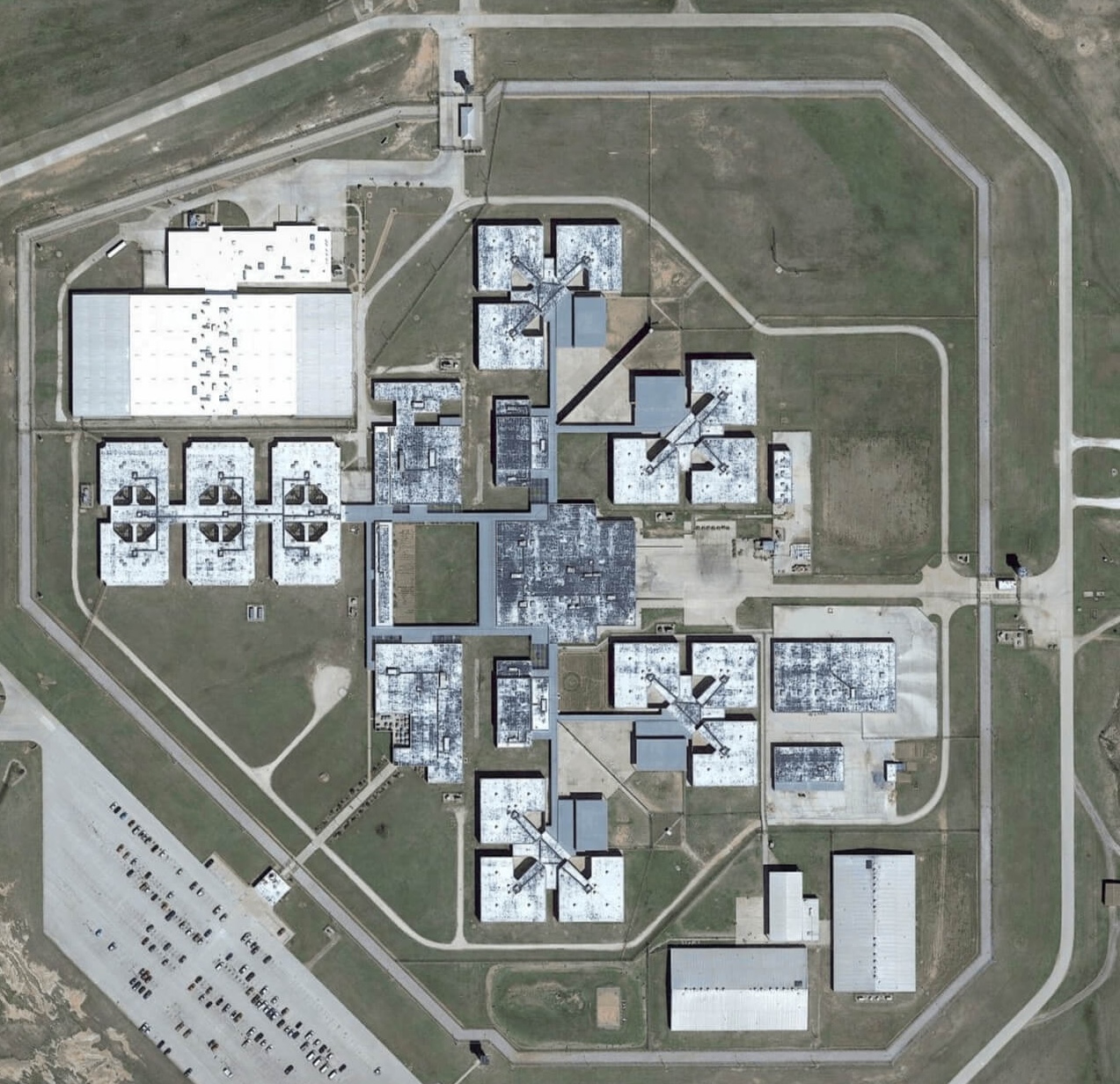

Prisons are parasitic. They consume time, space, resources, human potential, and our imagination of what’s possible. As a physical presence, prisons colonize the landscape, increasingly so it seems as capitalist crises lay waste to human potential. To shield this archipelago of confinement from criticism requires dispersing unfreedom across a vast territory. Mass incarceration requires mass consent. What might help us see the sheer scale of our commitment to locking people up? Ironically, another instrument of social control and surveillance, the satellite. With a bird’s eye view, it becomes possible to take in how prisons, in all their architectural and agricultural diversity, are etched into the land. Carceral technologies are made apparent. Fences. Gun turrets. Building and wing isolation. Copious concrete. Breaking the spatial monotony are scattered recreational spaces, courtyards, the occasional tree, rows of crops. Take a more zoomed out view and it becomes apparent that prisons also break up or slot into landscapes. From farmland and coal country to rural towns and the suburbs, incarcerated people are severed from the world around them as they grow food and raise animals.

Abolition as a desire and a practice builds worlds of care, community, and connection that obviate the need for cages and cops to begin with

The effect of showing these prisons at different scales is to expose the reach of incarceration, to turn an instrument of mass observation, the satellite, against the prison system. Abolition requires a consciousness of the task at hand. Telling stories, visually and otherwise, helps to generate urgency and action. In this case, we can imagine and work toward the removal of prisons from the landscape. Doing so would free up resources to restructure society to meet our collective needs so that prisons don’t become the repository for a self-made crisis.

Abolition as contextual

Refuse data that is decontextualized. Instead, root data in history and place, connect it to primary accounts from incarcerated people, and redirect it toward advancing imagining abolitionist alternatives.

Murder! Theft! Vandalism! Moral panic screams from the headlines that society is degrading. Cherry picked statistics seem to confirm the need for more policing, more imprisonment. But behind the numbers are choices. What counts? What’s excluded? Who decides? We’re awash in numbers that are regularly spun to maintain the prison industrial complex.

When it comes to prison agriculture, until our work, there was no clear sense of the scale and scope of farming behind bars. This is not for a lack of data. Rather the data was hidden in annual reports, spreadsheets, websites, news reports, and the heads of individuals running operations. The lacuna opened the way for dominant explanations of prison agriculture: It reduces recidivism. It provides job skills. Hidden in these linear representations of cause and effect are complicated and connected local carceral contexts, which can be explored in one of our interactive maps.

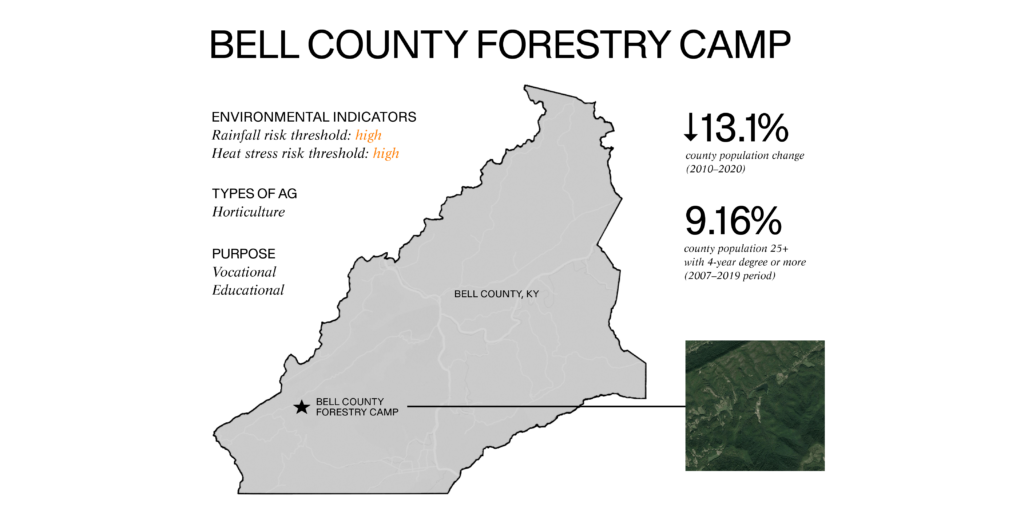

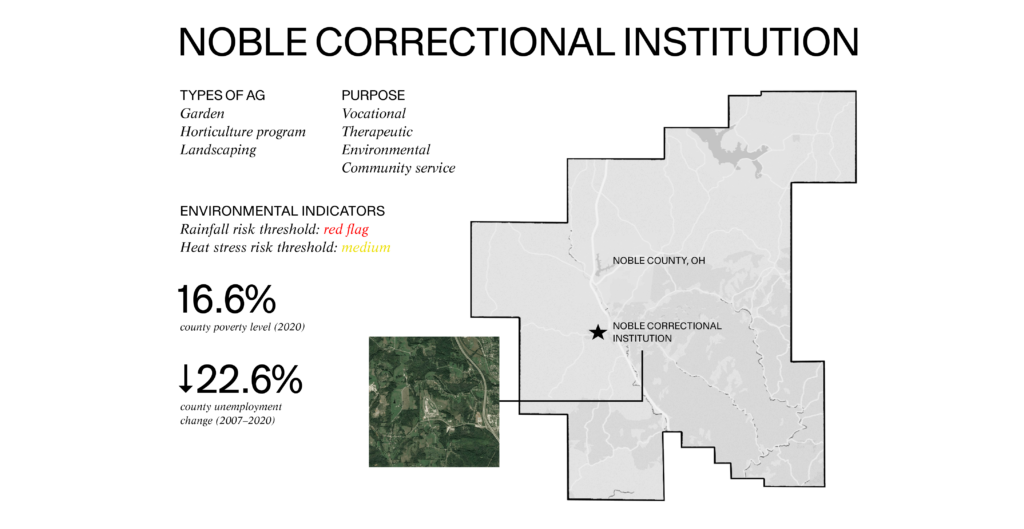

Take the Appalachian region, long dominated by coal, but now full of prisons. These prisons—most with agricultural operations—have been imagined as a fix to a deteriorating coal sector. With the support of the federal government, money is made available to build prisons on former coal mines. But upon closer scrutiny these are sacrifice zones with trashed ecosystems, impoverished people, and imprisoned populations. The organized abandonment of Appalachia’s coal and prison fields is clear by several measures: declining levels of employment, entrenched poverty, low rates of people with college degrees, and high rainfall and heat risk due to climate change. So for all the promise that prisons will solve the region’s economic woes, major social and environmental problems remain. If we are to imagine abolition in this case, it would entail freeing the region from its dependence on extractive economies so that the people whose environment has long been exploited and the individuals who’ve been relegated to cages can thrive.

Abolition as livingness

Refuse depictions of prison as humanizing. Instead, highlight incarcerated people—and the communities impacted by incarceration—in their “livingness” as already fully human and as maroon and fugitive producers of knowledge.

Philosophies of incarceration toggle between commitments to punishment and rehabilitation, a confined spectrum of possibilities that never questions the necessity of prisons. As two sides of the same disciplinary coin, these ideas undergird incarceration as a solution to a host of social problems. In the case of rehabilitation, the carceral humanitarian approach, proponents can claim their strategies better prepare formerly incarcerated people to reintegrate into their communities.

It’s within this paradigm that prison authorities promote gardens and horticultural training programs, to the applause of positive press. Prisoners will be “cured” of their criminal ways. Never mind that incarcerated people generally need to be a lower “security threat” to have the privilege of working with plants. The manipulation of the desire for greater freedom, built on hierarchies of deservingness, underlies such rehabilitative philosophies. But incarcerated people don’t need the sanction of the state for their humanity to be realized. Indeed, it’s in taking control of one’s restricted condition where true fugitivity, and therefore freedom lies. Matthew Hahn, formerly incarcerated in California’s Folsom Prison recounts the story about how he and others maintained a secret garden. Although they weren’t allowed to, these men grew and smuggled countless crops, from squash and peas to watermelon and tomatoes. Once inside, this bounty was shared and transformed into meals that reminded prisoners of home.

Or take the case of the “green zone” in Washington State Prison. Incarcerated people fostered alliances across social divides and the land on their own terms, even in a sustainability programming space that was technically “controlled” by the state. Modeled on the survival programs of the Black Panther Party, prisoners built autonomous rentable garden plots with a collectively pooled fund in a part of the yard that they repurposed. The money went back into seeds and worms to grow food that was healthier than what was provided in the chow hall and to share with those who wanted fresh produce but didn’t work in the green zone.

If we are to imagine abolition, it would entail freeing the region from its dependence on extractive economies so that the people whose environment has long been exploited and the individuals who’ve been relegated to cages can thrive.

Meanwhile, prisoners at Minnesota Correctional Facility – Lino Lakes have sought to hold prison officials accountable to a state law that requires prisons to start gardens if there is space and adequate security. There is an abandoned greenhouse of 24 years that prisoners—with the support of Metro State University’s college-in-prison program—successfully campaigned to get reopened and turned into a year-round food production site.

Taken together, these food sovereignty endeavors reveal the agency of incarcerated people to resist disposability under the constant vise of unfreedom.

Abolition as relational

Refuse pitting the incarcerated against the free. Instead, examine how racial capitalism and carcerality connect disparate people and places through producing unfreedom, and seek opportunities that foster accomplices for abolition.

By design, imprisonment strips people of their freedom. The civic death of sitting behind bars, with its curtailment on movement, expression, rights, and more, creates both a physical and legal division. Supporting narratives then claim that people deserve to be incarcerated and therefore do not deserve the same things as people on the outside: Do the crime. Do the time

But the division and control of carceral systems is far vaster. Take food apartheid. Access to healthy food is segregated through the creation of neighborhoods deemed undeserving. Redlining, racial covenants, public disinvestment in infrastructure, and more produce poverty. The response then is heavy policing, which leads to disproportionate levels of incarceration. Food retailers, like grocery stores, avoid such places. The cycles of abandonment and criminalization continue. Linking such conditions can stoke abolitionist food politics that disrupt the prison pipeline.

In Oakland, Planting Justice uses agriculture to connect people across the free/unfree divide. A third of the staff is formerly incarcerated, many from San Quentin Rehabilitation Center. They work alongside others to tend one of the largest organic tree nurseries in the country, plant community gardens, educate youth, and more. Not only are people avoiding reincarceration with healing horticultural practices, but they are also challenging exploitative conditions like prison slavery.

Across the country in the Hudson Valley of New York, Sweet Freedom Farm operates as a network of farmers, organizers, and abolitionists linking the food needs of low-income people and incarcerated loved ones. The farm produces landrace varieties of wheat, corn, and sorghum, harvests syrup from maple trees, and trains Black farmers, including youth caught by the prison system. With the resulting bounty, they deliver food to Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

In the face of systems that curtail freedom, farming in the caring hands of those committed to liberation bridges divides. The resulting bridges connect rhizomatic networks of abolitionists who not only grow food, but grow more free spaces.

Sowing the Seeds of Abolition

Growing food in prisons is not going to solve the problems of racial capitalism. The dehumanization and dislocation that feed people into the jaws of the prison system must be directly confronted. From our vantage, this requires first seeing prison agriculture as a carceral practice, one of many that captures social wealth and funnels it into punishment. We should instead use our social wealth to support aspiring poor, Black, and Brown farmers outside of carceral systems. Dismantling prisons would help advance such a food justice vision. .

Back in Missouri, there are many overlapping abolitionist efforts that reveal the need to starve prisons of resources so that community vitality and justice can thrive. The recent victory by a community coalition to close St. Louis’ notorious Medium Security Institution (the “Workhouse”) is particularly noteworthy. Breaking down also requires building up. After the murder of Michael Brown, Hands Up United formed to organize against police violence and develop community care programs like Books and Breakfast and the People’s Pantry. There are also food justice efforts to build a Black and Brown self-determined food system throughout St. Louis. From the small solo Heru Urban Farming operation and neighborhood City Greens Community Garden to the mission driven Agriculture for Community Restoration Economic Justice and Sustainability and Rustic Roots Sanctuary, liberatory visions abound.

These experiments in abolitionist living are seeds for a future where people and plants both grow free.

Data Visualization by Isabel Ling and Kristi Huynh.