This story is from the forthcoming print issue of MOLD magazine, Design for a New Earth. Pre-Order your copy here.

Kwame Ture, as quoted by jackie sumell“When you see people call themselves revolutionary, always talking about destroying, destroying, destroying but never talking about building or creating, they’re not revolutionary. They do not understand the first thing about revolution. It’s creating.”

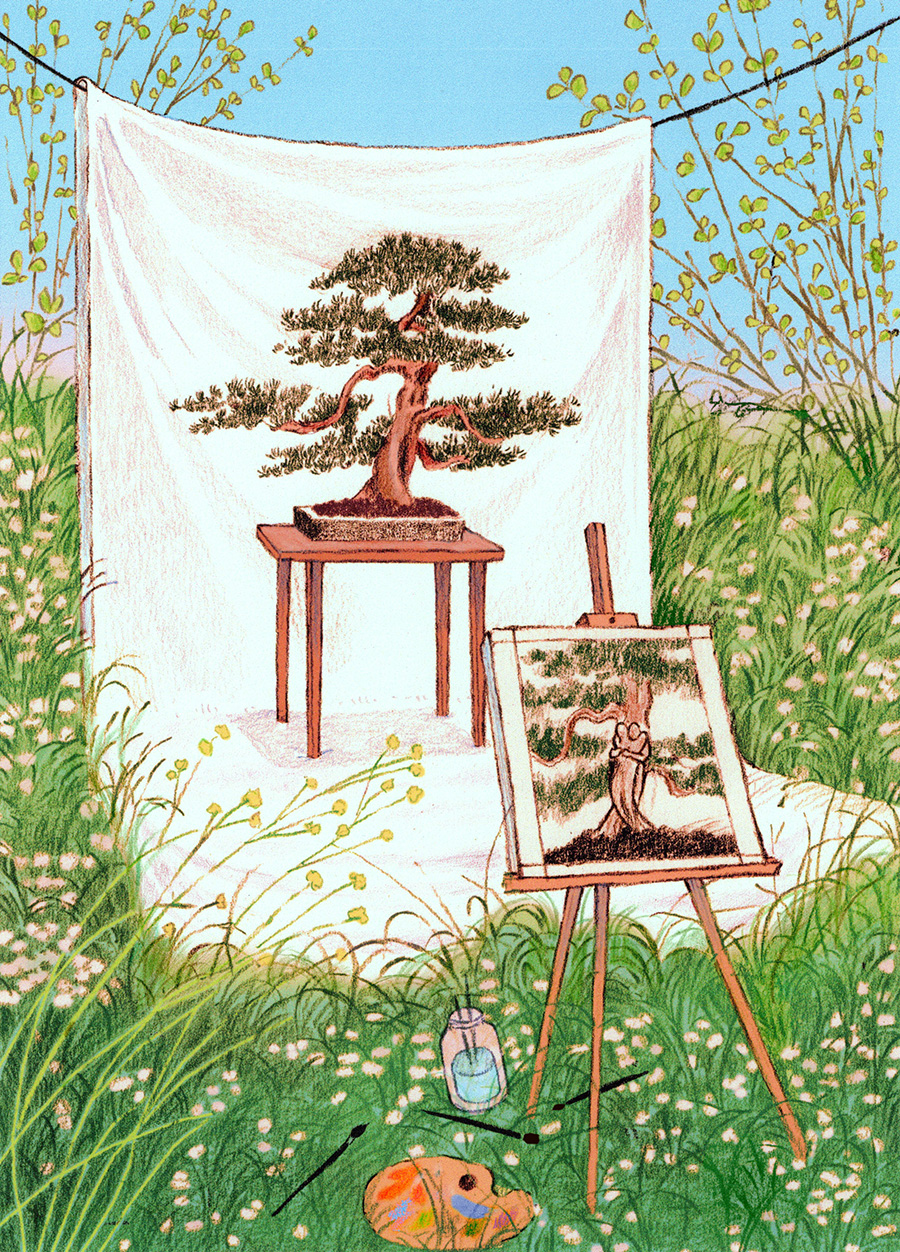

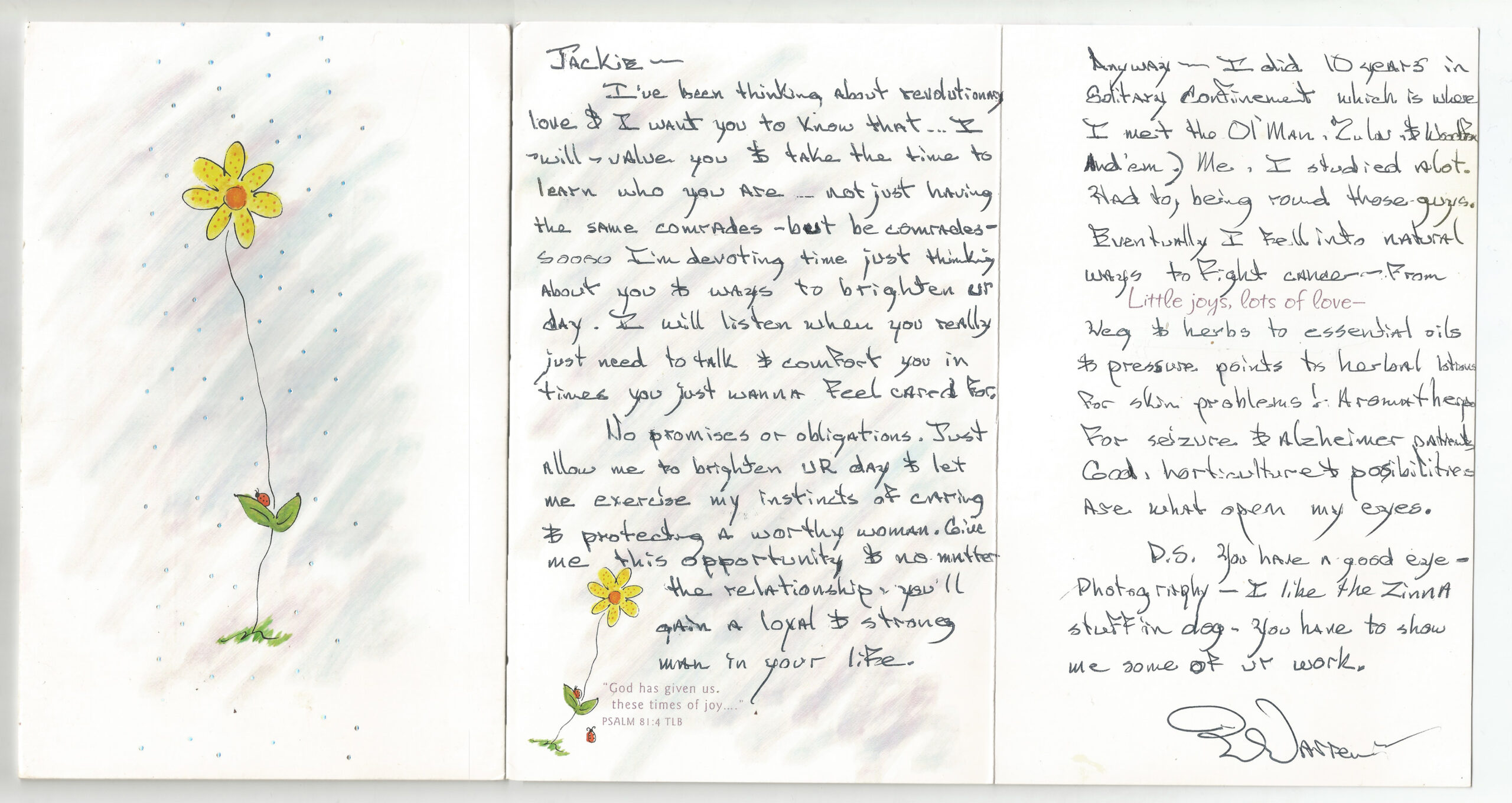

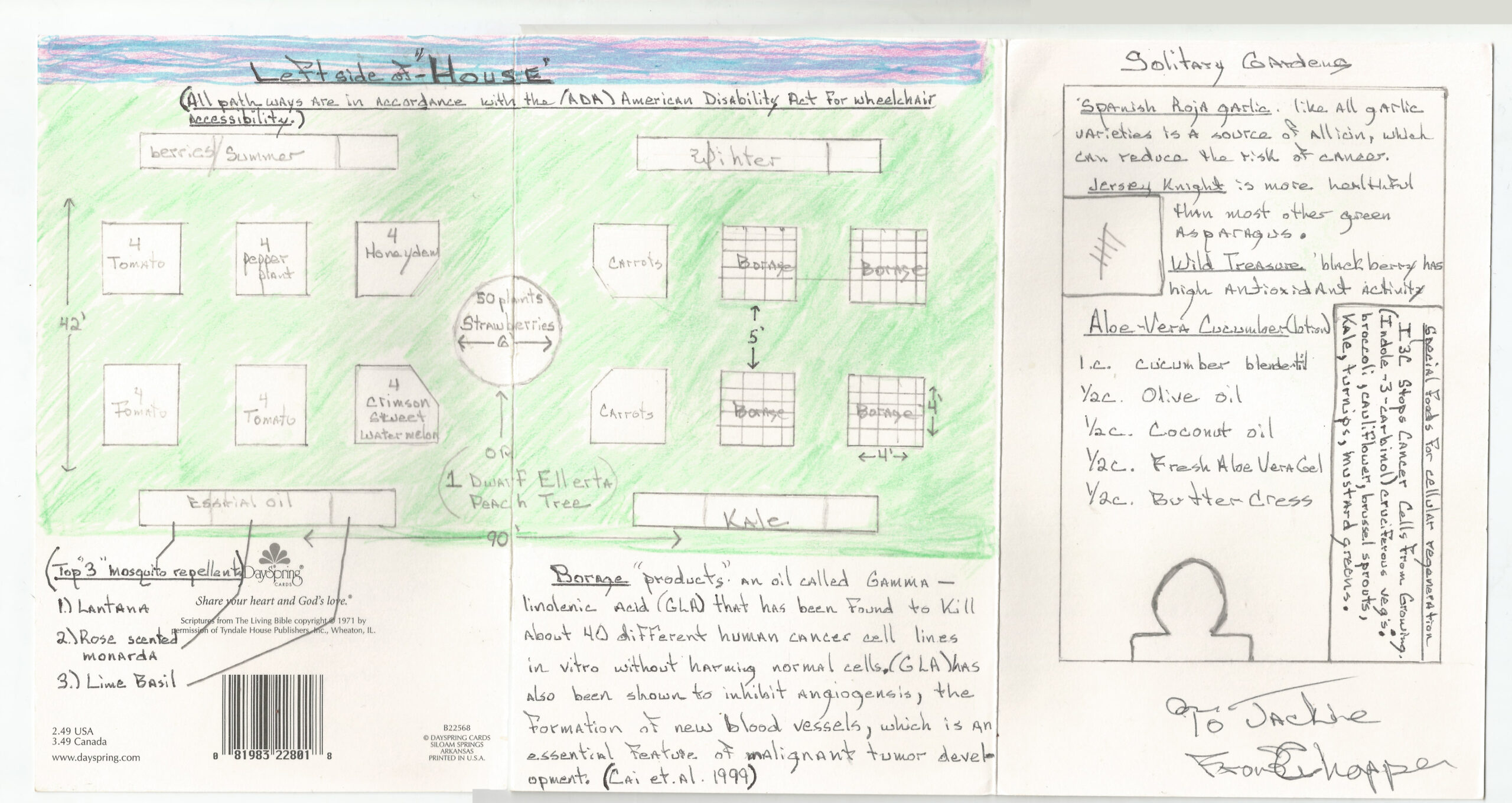

The Abolitionist’s Field Guide was initiated by New Orleans-based artist and abolitionist jackie sumell. The Field Guide, which takes the form of a workbook, is part of a growing ecosystem of projects grounded in the abolitionist imaginary, nurtured by jackie, and collectively titled “Solitary Gardens” and “Growing Abolition”. Like all of her work over the past 20 years, the Field Guide was germinated with the labor, inspiration, love, experience and visions of currently and formerly incarcerated people. She describes her journey to a deep and intimate connection with gardens as being facilitated by a series of spiritual downloads; epiphanies, openings or revelations during times of grief that made the relationship between abolition and the natural world undeniable.

Addressed to those who have a soft spot for plants or even a passing curiosity about our (mostly) green siblings, The Abolitionist’s Field Guide is a clear and tender manifesto for caring for and being cared for by them. It advocates for a practice in mutuality. The book’s core assertion is that plants can help us become the people we need to be to dismantle the cruel and brutal prison system, end cycles of harm and “imagine a landscape” without prisons. “I was disoriented and grieving when Herman [Wallace, a political prisoner who was a longtime collaborator of sumell,] passed and I was going through all these letters we had shared. I noticed how much he actually talked about plants, flowers and wood, and how, in contrast that was from being held in concrete and steel,” jackie shares. Serendipitously, when I first opened the book, a page fell out that simply read, “Plants teach us how to be better people.” Certainly, reading this book made me want to be a better person.

Filled with detailed drawings, poetic texts, affirming quotes and lots of space to draw, make art, write and doodle, the Field Guide asks us to reflect, to reconnect to the land and to be in deep relationship, so that we can relearn abundance and amplify love. It offers a safe and nurturing space to articulate the boldest ideas—that prisons do not work, that slavery has not ended and that, therefore, abolition is necessary, possible, inevitable. It does this by reminding us of shared values of patience, interdependence, care and mutual aid and ways that we can practice these values as a way of life. I spoke with jackie to learn more about how the practices shared in the book show up in her life.

Aisha Shillingford:

If we could throw a dinner party with food and drink that help to cultivate an abolitionist future, what might be on the menu?

jackie sumell:

Abolition is very much the fable of stone soup. What we each bring to it makes it better and very much informs it. What is exciting to me is how we are growing and learning together. There is this rhizomatic or non-hierarchical experience that actually diversifies and strengthens what we believe to be the direction of abolition. It’s not a place that we land or a target that we attain. It’s ever-forming and changing shape. It’s a direction. There’s always the possibility to grow.

AS:

At its core, abolition is about our collective capacity to imagine other ways of living. Why is imagination so key to making abolition possible?

js:

I learned about this while deeply embedded in carceral institutions. The first target of oppression is always the imagination. There is nothing more revolutionary than owning your imagination. If the oppressor owns your imagination they can define your core values and beliefs. A sense of possibility is crucial to abolitionist work. The imagination is a superpower. This is why historically, in the colonized US, artists and writers are part of the capitalist imaginary.

Abolition is a worldview, a spiritual practice, a willingness to see beyond what is and ask “what if?” It isn’t a set of rigid frameworks or rules but rather the simple recognition that abolition is what is already happening all around us in the human and non-human world.

AS:

What are your wildest dreams for how people might use the Field Guide?

js:

In my wildest dreams the Field Guide will be a launching pad for many pathways of accessing its ideas. Somebody will work with me to distill the Field Guide down to make it accessible to even younger people. It will become a catalyst for more people to go outside and connect with the natural world. Through the lens of the Field Guide, abolition is a worldview, a spiritual practice, a willingness to see beyond what is and ask “what if?” It isn’t a set of rigid frameworks or rules but rather the simple recognition that abolition is what is already happening all around us in the human and non-human world and that we can all be abolitionists, if we are willing to have the courage to be curious about all the possibilities that exist and acknowledge that we are always moving, changing, and growing.