Convivial Cosmogonies is a series that examines culinary labor practices and their material origins.

When we consume food, the processes of eating and digestion are an act of transformation, an essential metabolic process to nourish our bodies. In doing so, we open the body to a digestion-catalyzed physiologic effect, allowing ourselves, in turn, to be transformed from the inside. This potential for transformation is what provides certain foods their spiritual or cultural weight. Here, food simultaneously operates as object and portal – even totem or talisman.

It is no surprise then that the edible occupies a powerful mobilizing narrative function in folklore, myths, and religion. From communion wafers and wine to the magic beans from Jack and the Bean-stalk, through eating you become more than you, perhaps even beyond or outside of you. In the intimate act of eating there is a dual gesture of becoming closer to that which one consumes, and simultaneously grappling with where you end and it (the eaten) begins — a negotiation that often elicits a kind of pushing away or distancing. The physiologic effect of the eaten on the eater can range from poisoning to calming to hallucinogenic depending on the body being consumed and the body/bodies doing the consuming. Sometimes, the effect affords you access to something like an alternative register of perception. Take the pepper: capsaicin, the chemical component that gives peppers their heat, repels and attracts, at once serving as a defense mechanism against wild animals by effectively functioning to mimic a burning sensation through irritation, while also serving as a fundamental sensation (read: flavor) in human cuisine. Or alcohol produced by fermenting fruits or honey— baffling to some animals that happen upon it but sought after and cultivated by humans. Through eating, the effect remains the same, but the nature of the cause becomes chemically and biologically obfuscated. Mark Fisher describes this feeling of the encounter of the alternative register as equivalent to the floor falling out beneath you or a sudden change in gravity: “‘Cognitive estrangement’ here takes the form of an unworlding, an abyssal falling away of any sense that there is any “fundamental” level which could operate as a foundation or a touchstone, securing and authenticating what is ultimately real.” 1

- 1. Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie.

In Italian Folktales, Italo Calvino took on a culturally significant project of aggregating and curating a selection of pan-Italian folktales. The collection reflects an impulse to better understand the Italian folktales by identifying myth types and tropes that establish, reestablish, and affirm a communal and shared syntax. A particular folklorist term that helps to describe some of these recurring tropes is the ‘mytheme’. Claude Levi-Strauss identified the mytheme as the original unit or kernel of a story from which a range or lineage of narratives are generated (ex: a devastating flood or the orphaning of a protagonist). Food is often a powerful narrative tool in the stories collected by Calvino, with characters becoming food, originating from food, traveling for food, transforming food, or exchanging food (all potential mythemes). One of the more fantastical mythemes or tropes is the young girl as fruit, Ragazza Mela (Apple Girl), which begins: “There was once a king and a queen who were very sad because they had no children. The queen repeatedly asked, “Why can’t I bear children the same as the apple tree bears apples?” Instead of bearing a son, the queen gave birth to an apple, but an apple redder and more beautiful than any you ever saw”. The king places the apple-child on a gold tray on his balcony and the apple becomes the object of admiration for a neighboring king when Ragazza Mela emerges from the apple to bathe. A jealous stepmother interferes but ultimately Ragazza Mela marries the neighboring king. Beauty and purity is represented by the fruit and the tale moves fluidly between the symbolic and the actual apple with Ragazza Mela being the apple but also somehow held inside of the apple, thus building and rebuilding a bridge between the symbol and its meaning. In his 1967 lecture Cybernetics and Ghosts, Calvino elaborates on the establishment of myth and symbolic narrative: “Myth tends to crystallize instantly, to fall into set patterns, to pass from the phase of myth-making into ritual, and hence out of the hands of the narrator into those of the tribal institutions responsible for the preservation and celebration of myths.” The perpetuation of the story itself becomes the ritual act; an act of communal maintenance of a shared vocabulary of symbols. Antonio Gramsci also describes this chain of modifications/rituals and grounds it in material circumstances:“Folklore can be understood only as a reflection of the conditions of cultural life of the people, although certain conceptions specific to folklore remain even after these conditions have been (or seem to be) modified or have given way to bizarre combinations.”2

- 2. Gramsci, Observations on Folklore.

When baked with dough, the ergot transforms into a form of LSD

While Ragazza Mela nods a bit to religious iconography it is not so explicitly interested in the specific characters, and certainly not the morals, of Christianity. Religious foods rely heavily on their transportive, transformative, and ultimately transcendent qualities as embodied and embody-able material gestures at what is ineffable (or the unembody-able). The Eucharist is in some ways the officially sanctioned version of these transformative or portal foods, with the idea of transubstantiation transforming the wafer (standing in for the bread shared at the last supper) and the wine into actual flesh and blood to be consumed in an act of devotion and recognition of Christ’s sacrifice. Julia Kristeva says: “The division within Christian consciousness finds in that fantasy, of which the Eucharist is the catharsis, its material anchorage and logical node. Body and spirit, nature and speech, divine nourishment, the body of Christ, assuming the guise of a natural food (bread), signifies me both as divided (flesh and spirit) and infinitely lapsing.”3 Kristeva situates this lapsing within a broader discussion of purity and the abject, drawing attention to the specific moral nature and even simply the presence or absence of food (in the case of a fast for instance) as powerful tools to guide religious practice and systems. For Kristeva, food is situated within or even as a threshold itself between self and other, nature and culture, pure and impure, human and non-human. The Eucharist certainly functions this way, but so does any food which introduces the products of a given landscape into the human body and, in so doing, alters the body in question.

- 3. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection

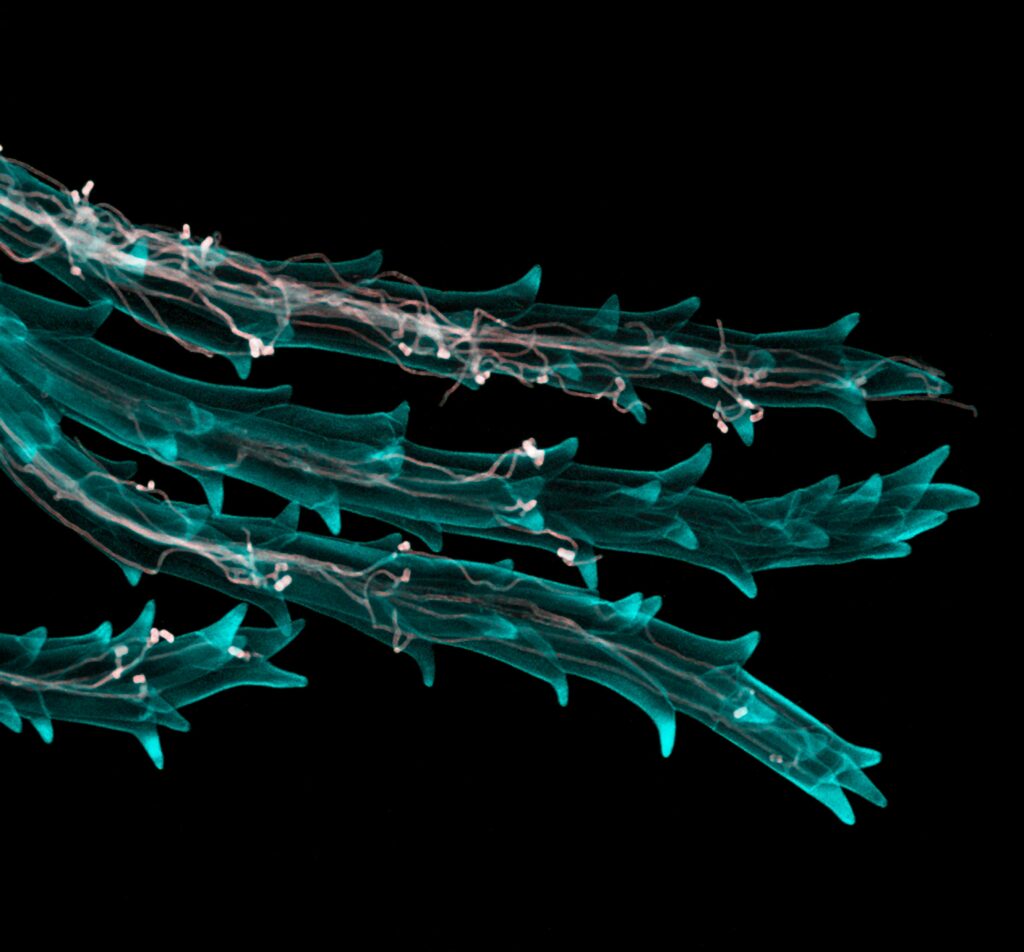

Foods that encourage traversal between registers of reality certainly exist in folklore and ritual (for example, votive foods) , but those that create actual hallucinations are far rarer and almost never ingested without expressly seeking their hallucinogenic effects. One such example is the Ergot fungus, Claviceps purpurea. The fungus infects the ovary of the host plant, usually rye, though it can infect a range of similar plants, and replaces the plant’s kernel with a sclerotium, which takes on a form resembling a dark almost purple protrusion or horn growing from the site where a kernel would be. During the initial infection of the rye ovary, the fungus directs the secretion of a liquid “honey dew”, which then attracts insects who help to spread spores to adjacent plants. The structure hardens producing the sclerotium or ergot kernel which functions not unlike a plant seed but is made up of hardened fungal mycelium and enough food stores to last until optimal conditions for germination are reached. Within the ergot is an alkaloid compound, ergotamine, which is capable of causing strong hallucinations, among other effects. When baked with dough, the ergot transforms into a form of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). There are two types of ergotism: convulsive and gangrenous . The former is responsible for several effects on the central nervous system in the form of spasms, hallucinations and epileptic fits, while the latter damages less well-perfused extremities, such as fingers or toes (and in the worst cases, leads to their loss). Ergot is currently allowed in global flour supplies but only at controlled levels, otherwise it is cultivated for medical uses. Despite its potential to poison, ergot has historically been used by midwives in childbirth and its medical uses have only increased with the use of ergot-based medications like methylergonovine (also called methergine), used in obstetrics for postpartum hemorrhage, or dihydroergotamine and ergotamine, used for migraines.

Limited primarily by plant type and environmental factors, ergot’s presence can be found just about anywhere and anytime its preferred conditions were met. Around 350 BC, in one of the sacred books of the Parsees, descriptions were found of ‘noxious grasses that cause pregnant women to drop the womb and die in childbed”. Ergot’s presence has been found in the gut of the Grauballe Man, a bog body dated the late 3rd century BC, likely a result of recorded so-called “outbreaks” of ergotism throughout the history of Medieval Europe and up until as recently as the late 20th century. Ergot is responsible for a range of notable periods of hysteria and tumult, gaining the names Ignis Sacer, Holy Fire, and “St. Anthony’s Fire,” after the monastic order that became skilled at treating its effects. Ergot has more recently been at least partially blamed for witch trials throughout Europe and North America (most notably Salem, where it is theorized that ergotism affected individuals with stomach ulcers in particular.) A well-documented outbreak occurred in the small French village of Pont Saint Esprit in 1951 when a local baker received a tainted bag of flour from a miller who was willing to look the other way when a bad batch of grains was delivered for milling. The town experienced 250 or so cases, with doctors and newspapers documenting the vivid and elaborate visions of those infected:

Day of St. Anthony’s Fire, John G. Fuller“There was the woman with delusions of grandeur, who insisted that she was a baroness and screamed that she was being persecuted when they dragged her through the hospital doors. There was the woman who was absolutely certain that her three children had been drawn and quartered and were hanging from the rafters of the attic to be made into sausages. There was the man who clutched his head because he was sure that red snakes were eating his brain. There was the man cringing and twisting his body in contortions because there were bandits with huge donkey ears chasing him. There was the seven-year-old child whose every toy changed suddenly into a fantastic, indescribable beast….There was the man who saw the hospital attendants as giant fish with gaping mouths, ready to eat him alive… Some heard giant celestial choruses singing in the heavens above. Others saw flaming, gorgeous bouquets of flowers growing suddenly out of their hands and feet…Some saw in the most ordinary things – a thimble, a fingernail, a shoe – the whole essence of the world and the universe, a revelation they had never had before, a great religious mysticism.”

An outbreak of ergotism (the contamination of a grain with the fungus ergot) at the beginning of the 20th century, occurred on the Sicilian island of Alicudi where stories of flying witches and other folktales seem to begin in the years in which ergotism was most prevalent. The hallucinations and retellings of them allowed for their assimilation into local mythologies and folk knowledge. Even within families there would be stories of so-and-so’s great-great grandmother flying across the ocean one night. The nature of the hallucinations were consistent enough in quality and content to become entrenched in a collective narrative. The function of the individual’s re-collection of unknowingly altered sensation contributes to a collective experience – a collective recollection within a social body rather than an individual, with the output being a re-collected history that serves to describe a fundamentally indescribable and potentially alienating experience. The infected grains and the resulting bread operate as a threshold, catalyst, or portal depending on your vantage point.

The importance of ergotism in the construction of myth functions in a couple of ways. The first, in the potential creation and evolution of folk knowledge. In the case of ergot, this can be stories of vivid visions or simply its use in healing practices. The second is the wielding of the social effects of ergot in pursuit of a specific agenda. For example, the witch hunts, which were either exacerbated or initiated by ergotism outbreaks, resulted in the systematization of hunts which were executed on an almost industrial or military scale. It is important not to place the blame on ergot hallucinations exclusively, but rather to note the narrativizing of certain behaviors by even and especially the non-infected. Ergotism is also blamed in part for the Great Fear leading up to the French revolution, implicating the fungus in a number of historically significant moments that saw the movement or consolidation of power. As a fungus it is more interested in its own perpetuation than that of its host, and with its genesis in fields of cultivated grains as the only hint at its place in relation to humans and no such grand visions to speculate about among the other sclerotia. Its appearance in the realm of the edible implicates it in the “falling-away” or “lasping” that is found primarily in religious foods, placing it in a rarified category of transformative foods that invite, or indeed insist, the eater reckon with the ineffable within the mundane and necessary act of eating.

꩜ Rye toast with braised mushrooms ꩜

Slice and toast a high quality rye bread in butter or oil until golden.

Sear mushrooms (oyster, maitake, porcini, or a mixture) with a slick of oil until browned. Add a whole garlic clove, salt, pepper, and a fresh woody herb like thyme, rosemary, or bay and cook until the garlic is slightly browned. Add a generous slug of wine or a dry (alcoholic) cider, the mushrooms should be almost swimming. Allow to reduce until mushrooms are cooked through and the liquid has all but completely absorbed or evaporated.

Top toast with mushrooms and more herbs and serve.