MOLD’s series on Degrowth explores how activists, farmers, and scholars have sought to create more resilient communities and food systems in rejection of the drive for infinite economic growth.

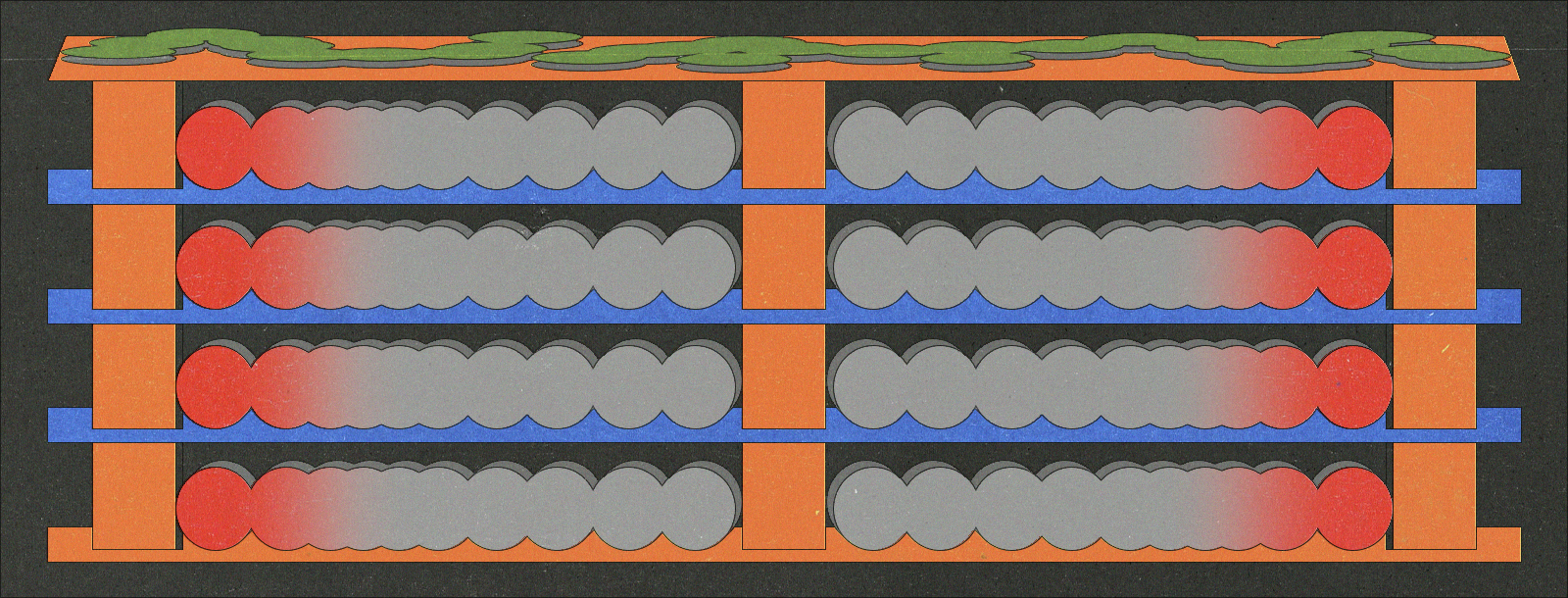

The first early months of the pandemic placed the frailty of our food systems firmly in our collective sightlines. Images depicting farmers next to large piles of rotting produce —symptoms of fractured supply chains— were frustratingly incongruous with empty grocery shelves and rampant food insecurity across the country. In response to these seemingly inconsistent realities, Star Route Farm made the decision to take direct action to feed their neighbors. Located in upstate New York, this seven-acre farm has committed to growing solely for mutual aid.

Previous to the pandemic, Star Route had primarily grown vegetables and grains for restaurants throughout New York City. After losing the majority of their customers due to restaurant closures, Star Route began distributing their produce to food pantries who had been given money from New York State to purchase from in-state farms.

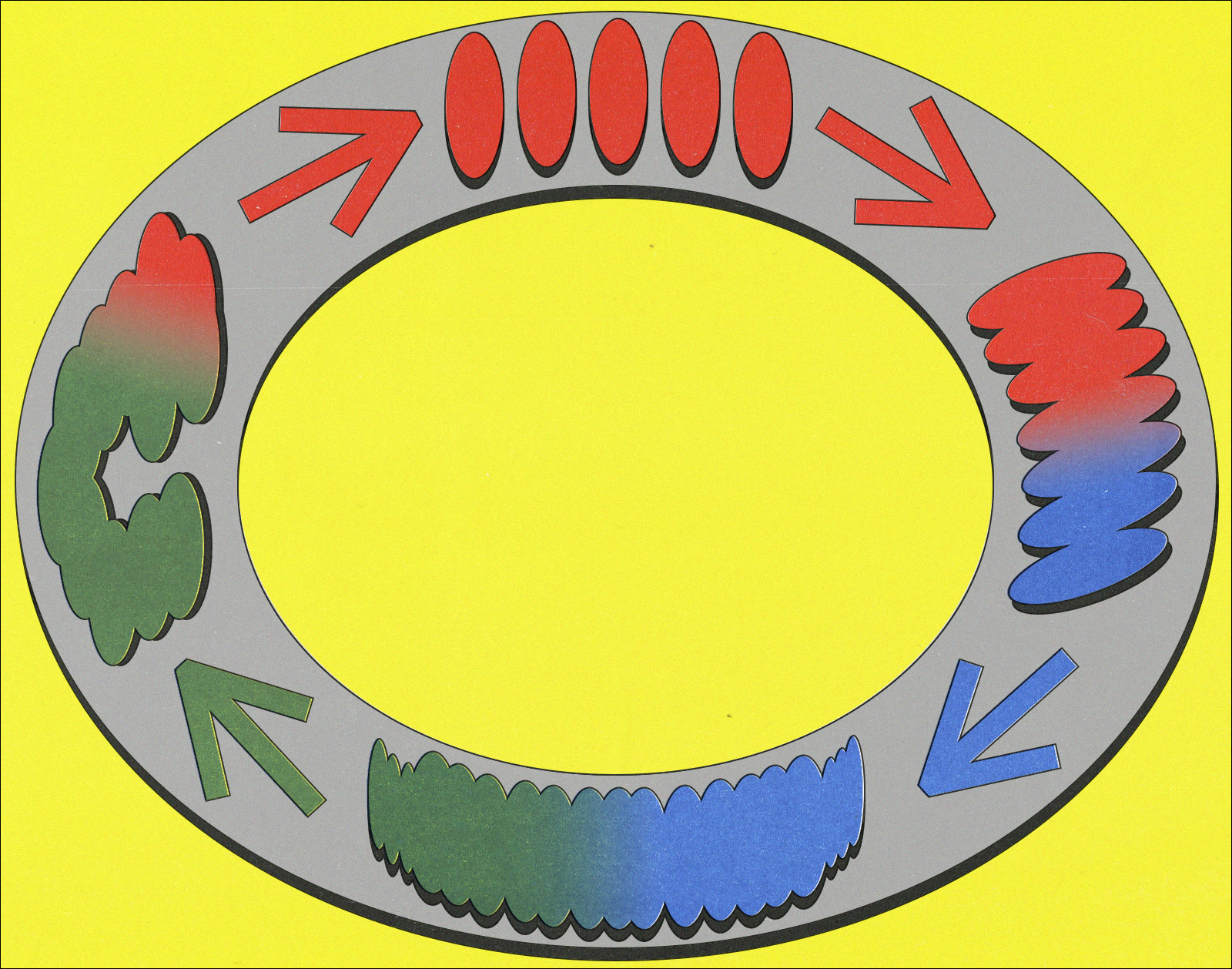

For the farmers at Star Route, the disruption created by the pandemic presented a portal through which to think differently about the purpose of farming. This, in tandem with a summer of social unrest in response to George Floyd’s murder, demanded a fundamental re-prioritization of community and food access in the farm’s practice.

According to Amanda Wong, a farmer at Star Route, the decision to transition to full-time food sovereignty work was a natural next step after a summer of farming for food pantries, “It feels like we are part of a larger push on a community level that has come with the complete and utter failure of the government to do its job and a [resulting] loss of trust by the people who rely on their systems.”

Farming is so much more than a business, it is constant maintenance it is a conversation with the plants, it’s more like a baby than a business.

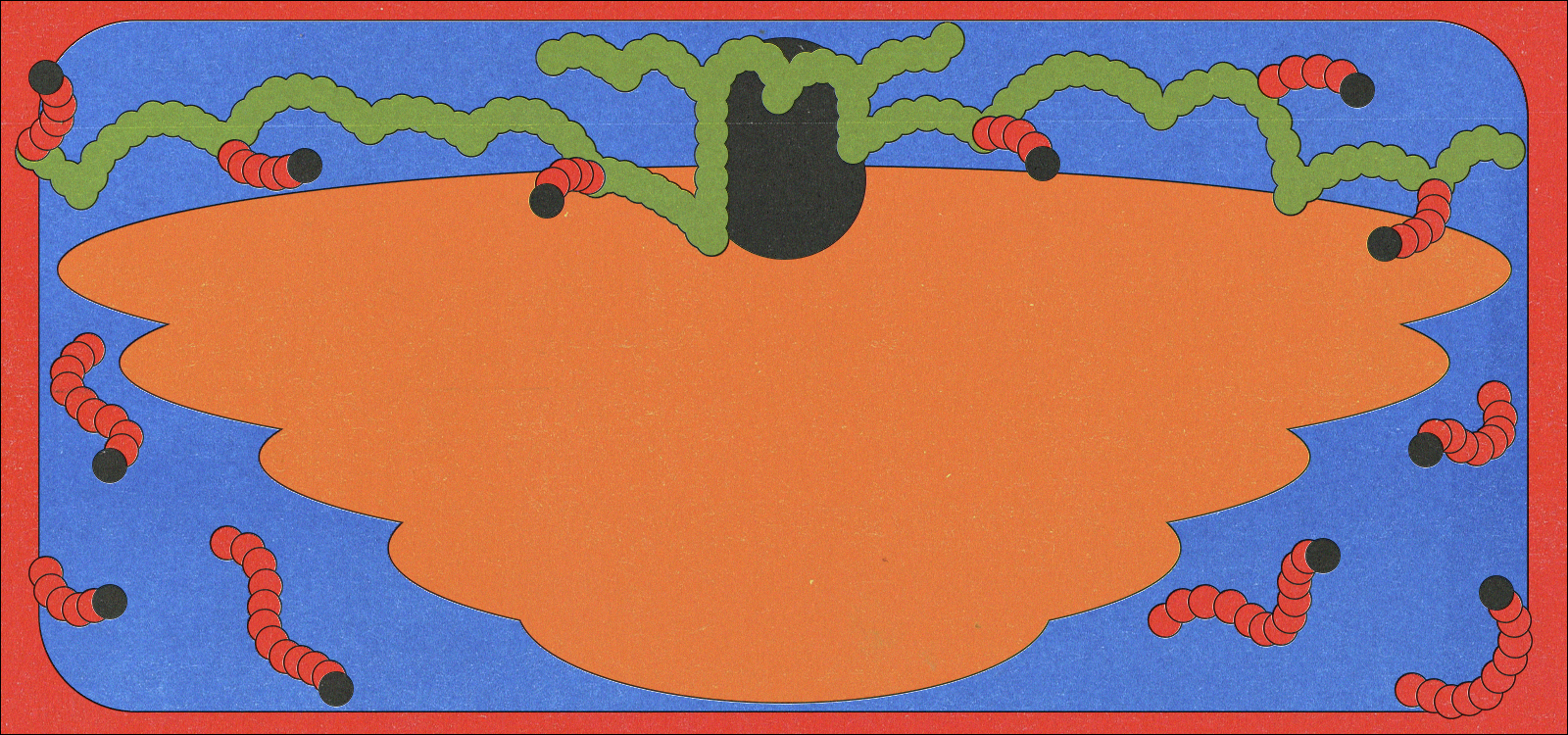

So far, Star Route has partnered with mutual aid organizations like Bushwick Ayuda Mutua and Heart of Dinner in order to provide produce directly to food-insecure communities. The farm plans to fund this work long-term through a combination of grants and donations. As of April, the team has been able to raise a little over $27,000 dollars to support its efforts via GoFundMe.

“Working with and connecting with these community organizations is exciting to me because it makes high quality food more accessible to people like me,” says Wong, “Before, I wouldn’t go to farmers markets because I couldn’t afford organic vegetables and as a farmer I definitely can’t afford to eat at farm-to-table restaurants.”

Collaborating with community organizations has also created opportunities for the farmers to cultivate produce that is not only nourishing but also culturally specific. As I spoke to Wong and her fellow farmer, Walter Riesen over Zoom, Star Route had just delivered one hundred bags of rice and produce to Wat Buddha Thai Thavorn Vanaram, a Buddhist temple serving Thai, Chinese, Laotian and Burmese communities in Elmhurst. Farming to meet the needs of a community has meant that the farm will be seeding vegetables like bok choy, gai lan and Napa cabbage this spring.

“It really helped me to reconnect with my Asian heritage,” says Wong, “Previously, we would grow these Asian vegetables and they wouldn’t sell because there isn’t that much of a market for them, now that we are growing for these specific communities we are able to grow more diverse vegetables.”

On a more personal level, the transition has made farming more fulfilling for Wong, “As a farmer you’re not paying me nearly enough for me to approach this simply as a job, farming is so much more than that, it is constant maintenance it is a conversation with the plants, it’s more like a baby than a business.”

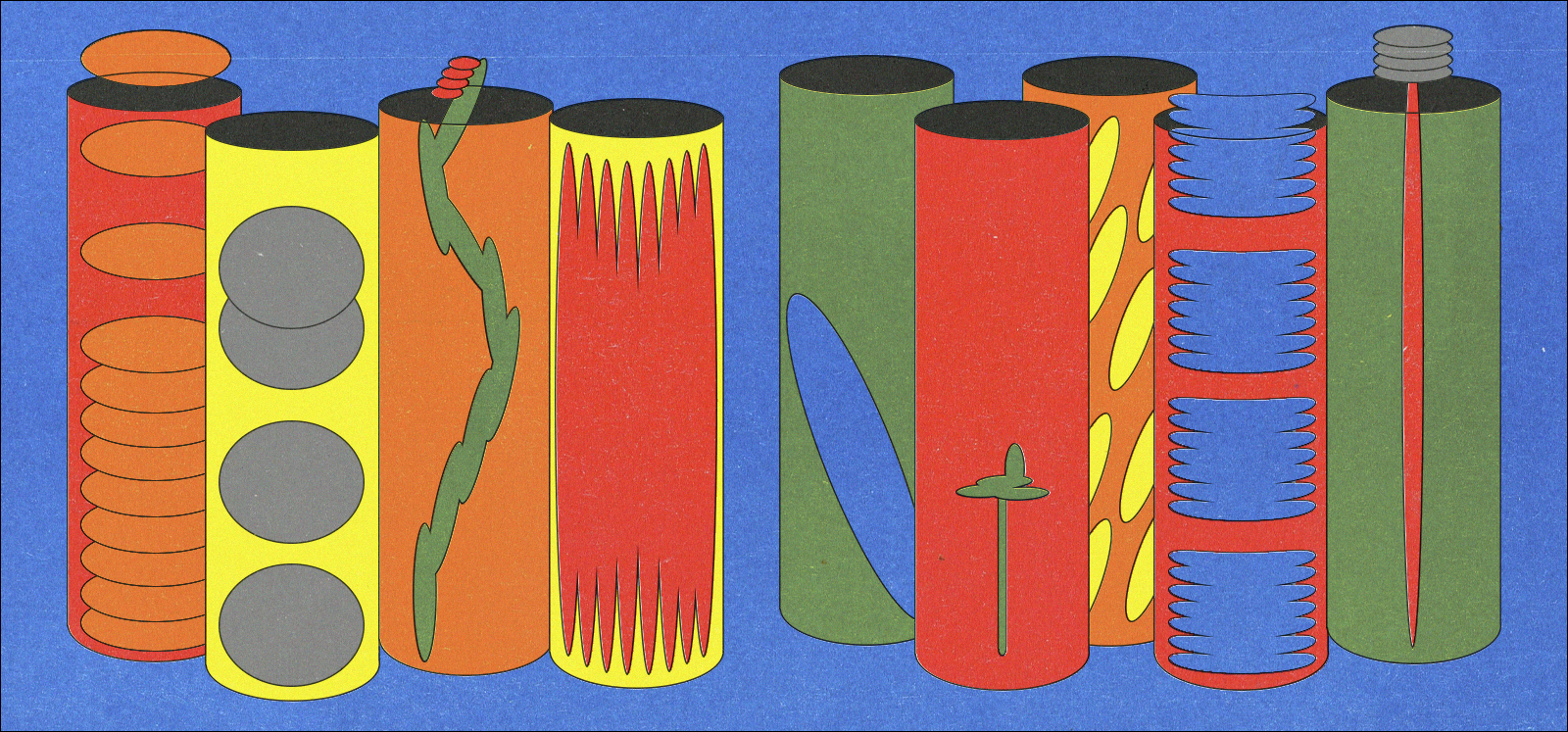

In the centering of community, Star Route has created what feels like a more logical paradigm of thinking through which to approach the intense labor demanded of farmers. “Farming is my art practice now,” says Riesen, who like many other members of Star Route’s small team, doubles as an artist, “It is a very beautiful thing and a beautiful life that you build. If you approach farming from a bottom line perspective it’s not sustainable because it’s so difficult to make a profit.”

Prior to our interview, both Riesen and Wong had not heard of the term degrowth, but expressed surprise at how accurately it described the ethos behind their work with Star Route. Degrowth is a strategy that has at once been formed out of necessity at the precipice of climate catastrophe, but also speaks to a general condition of searching instilled by a lifetime of living under capitalism. Whether the answer to these questions is happiness, community, or meeting the basic needs of ourselves and our neighbors, it quickly becomes clear that the world is governed by systems of logic whose priorities don’t necessarily align with what feels deeply intuitive to the human experience. Star Route is an experiment in what it means to seed one’s own answers to such questions , coalescing their practice under the motto “Farming Against This Mad World” in rejection of the current inextricability of food and profit.

Like many farmers, Riesen and Wong take great pride in the vegetables they grow. Though they are small, Riesen argues that they are perhaps the most sweet and delicious vegetables one could ever eat. This is a result of calculated soil science and labor-intensive organic farming practices that encourage the plant to work harder to grow, its struggle producing a more nutrient-rich vegetable. Similar to their produce, Star Route Farm paints a picture of what our own food systems can become with collaboration and care, perhaps smaller, but also sweeter and more nourishing.