It was one of those incredibly hot days where the end of July blurred into August, and I had found myself on Henry Street, where the Q train crosses the Manhattan Bridge, its screeches and rattling echoing into street-level galleries and restaurants. Tessa Liebman, a chef, and multisensory artist was debuting a show called “Soft Fascination” at the Olfactory Keller Gallery, the only gallery in New York completely dedicated to smell. I first met Liebman while buying Frankincense to treat a cooking burn at an aromatherapy supply store, Enfleurage, a favorite amongst New York perfumers.

The basis for this new body of work was inspired on a groggy morning, when Liebman tuned into NPR after having some difficulty coming up with a new somatic project. “They mentioned in passing that there was another segment I could listen to about this phenomenon called soft fascination,” she remembers in a recent interview with MOLD Magazine. Her interest was piqued when she heard the letters A-R-T. Attention Restoration Theory (ART) examines the different stages of attention, and how humans are able to recover their focus and connect to a more creative state. The segment noted that even natural themes in art and media that mimic nature like recordings of bird songs, and videos of streams, could also bring people into this state of mind. Liebman tells me she had long been recreating experiences and triggering memories, with her practice, and she wanted to design some of her work to improve cognitive function, as “access to nature and the resources for relaxing, leisure time, etc. are seemingly out of reach for many who need it most.”

“Soft Fascination” is a part of Liebman’s ongoing project Scents of Plates, which surfaces the interconnectedness of smell and taste through multisensory experience kits, events, and “aromacandies”. As Liebman writes in the exhibition’s accompanying text, smell “goes directly to the hippocampus creating and recalling memories and emotions. Many of the memories we have around food are associated with smell and therefore evoke feelings of comfort, disgust, longing.” By isolating specific flavors and smells in a context focused on presence to detail, we increase our sensory acuity, which is the ability to detect sensory changes with accuracy and precision. The first experience kits Liebman ever made was titled “Smoke Show” and contain frankincense candy and resin incense, encouraging both olfactory and gustatory observation. With this sensorial engagement, she hoped to use smoke to tap into a collective memory, one that many have experienced sitting by a campfire, eating preserved meat, or sitting in a church pew.In “Soft Fascination,” she presented similar “kits” in a collaborative setting, calling them “Fascination Stations”.

At the first fascination station, titled Take a Hike, twigs, pinecones, moss, and branches were placed next to little glass jars of spruce tips. We passed around cotton balls doused with a mix of Blood Cedarwood and Douglas Fir essential oil. I took a sip of the accompanying cocktail and recognized the taste of foraged spruce tips I touched earlier, as well as chartreuse with its pine notes and herbaceous undertones.

The next station, Urban Petrichor, was designed to tap into our primal attraction to first rain. Wet cardboard mimicked the smell of the bundles of broken-down cardboard boxes that collect droplets of rain outside of bodegas and buildings. As we passed around the fragrance-coated cotton balls, I immediately identified celery, but there were also grainy citrusy notes that I later learned were attributed to vetiver.

With each new kit, the audience became more engaged, trying to guess what each concoction contained, occasionally getting stuck on the words to describe something we knew we had come across before. Many of the people in the room had an extensive knowledge of fragrance, however I also found that as a cook I held a certain advantage in the game of identification as well. Collectively we correctly guessed the ingredients of mezcal, celery and beets as we sipped on the second cocktail.

As humans we are always sensing, even if we may not always be paying attention

The final fascination station called Night Blooming Garden in the Mind, called on us to put our imaginations to work. The station was evocatively decorated with glass flowers from the artist Goldie Poblador and silken fabric Liebman had placed on the shelves. We sipped mixtures of gin, homemade lemonade, orange flower water, jasmine tea, ylang ylang aquafaba. The title of the station was perhaps inspired by the concoction’s inclusion of ylang ylang, which grows like a droopy yellow star on trees in southeast Asia, and is often regarded for its calming abilities.

As humans we are always sensing, even if we may not always be paying attention. “We have so many sensors all over our body that we don’t even have the words to explain,” Liebman told me in a recent interview, “Most people don’t recognize certain senses that humans have… our culture just focuses on the five, but there are many more including balance, temperature, and even chemical sensing”.

Soft fascination works in the background to provide positive feedback to our brains. “It’s things like ‘Yes, we’re gonna eat’ or ‘We’re gonna survive like this’, or even ‘Oh, there’s more sunlight. That’s gonna help my body make more cells’,” Liebman explained.

Soft fascination is not a new term. In the 1980s, Rachel and Stephen Kaplan, two psychologists specializing in the relationship between the environment and cognitive functioning developed this theory. After observing people’s behaviors in natural settings like parks and wooded areas, the duo designed experiments to test their hypothesis that natural environments had a positive impact on cognitive functioning. Developed within this research, soft fascination refers to the positive effects of nature and other aesthetically positive environments on mental wellbeing. This kind of attention is “necessary to address lingering, unresolved thoughts that could otherwise be a drain on attentional resources. ART describes this modest attentional hold as “soft” fascination. By contrast, “hard” fascination occupies the mind fully, leaving little space for contemplation”. (Kaplan, 1993, p 48). Nearly forty years later, these terms are still widely used. One is almost more likely to encounter ART in an urban planning course than they are in a psychology class.

Liebman realized that a lot of her work both as a chef and a somatic practitioner focused on soft fascination. Through her work, which asks us to relearn how to smell and taste, she creates space for awe— a state of being which has been shown to aid in recovery from burnout, ADHD, and PTSD.

After attending Liebman’s exhibition, I found myself in this soft fascination stage while at my professional cooking job. While shucking a couple of pounds of peas and picking marjoram, I noticed I was able to be present to the task, while also having some space to let my mind wander. I tried to appreciate the fibrous shell of the beans in my hands and noticed the floral notes in the air. Maybe despite the stress and pressure of cooking professionally, there were moments of soft fascination I could find in my day-to-day work.

To explore my own hypothesis around cooking’s positive impacts on our nervous system and whether it had the same effect as listening to birds sing, or going on a walk in the forest after a first rain, I reached out to neuroscientist Dr. Caroline Correcel who investigates food perception and eating behaviors across her practice. I was curious to hear her perspective on the ways in which the act of cooking itself might be restorative in the same ways as interacting with nature. We began to discuss anthropologist Richard Wrangham’s work Catching Fire; How Cooking Made Us Human which looks at cooking and the development of the brain. In this book, the author finds that modern humans are biologically dependent on cooking.

“There is brain imaging that shows our response to cooked food is much different than raw food,” Dr. Correcel Cooking has had a significant impact on how our brains respond to food, making it easier to digest and increasing the energy we can get from it. Cooking also helped compensate for the high energy cost of having a big brain, which allowed our brains to grow larger over time. We have co-evolved with the process of cooking itself, and to some extent, information seems to be taken in somewhat subconsciously. For example, you may find a cook manages to consistently make perfect pork chops, but they would never be able to quote the time it takes, relying on an internal sense of time, and sensory cues. Beyond a “cook’s intuition,” there are repetitive tasks throughout the day that allow for the opportunity to escape even the most stressful environments.

While sitting outside of Leila Allementari, Liebman and I chatted a bit more about attention’s role in cooking, “I discovered a long time ago, in my own very like a squishy, kid-like, tactile way that my job was different than a lot of people that I know because I get to, push and smell and taste different things all day…. and in this physical, stressful-ass job it is my secret pleasure”.

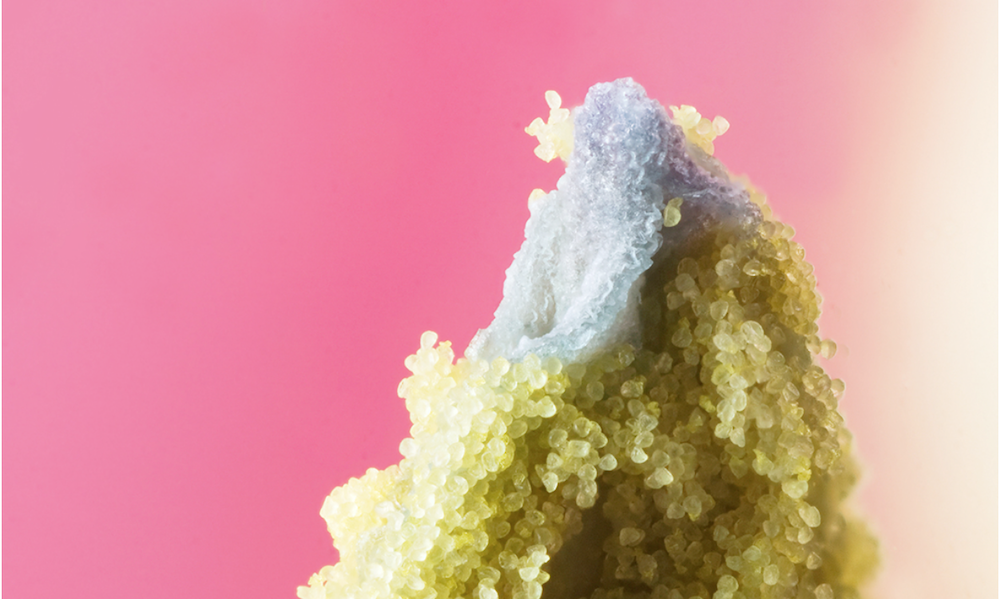

Liebman describes pleasure in the kinesthetic feeling of skinning a beet; “I don’t really talk about it too much, but I love the way it feels to slip the skin of a roasted beet, as you push against it and you feel it give and smash it’s off. There is a tension between pleasure and work; You can be there all day, like, like, you know, but it’s just one little beautiful sensation, much like smelling things and looking at colors.”

Cooking both at home and professionally, allows the ability to interact with a complex system of sensory information, and allows for a heightened awareness that can be easy to surrender to. An invitation of presence, cooking and the act of making invites us to return to our bodies.