Going Inland is a journal documenting the author’s participation in the Inland Academy and her reflections on her personal and professional relationship to rural spaces.

I was so excited to see the sheep, thrilled really. I was embarrassed by the giddiness that bubbled up inside me seeing their cute, fluffy wool and the newborn lambs just starting to walk next to their moms. I felt self-conscious about my eagerness, and a little confused by it. Why was I so excited to see these animals? What provoked such happiness, and was that feeling a surface-level emotion or did it connect to something deeper?

I will admit, with a bit of shame and a bit of pride, that I wore a themed outfit for our visit to see the sheep at Casa de Campo. I could frame it as practicality–being a cold day with a potential for rain and little shelter, a warm sweater and a scarf was a good idea–but I’d be glossing over notable details if I didn’t clarify I wore my sheep sweater and Little Lost lamb kerchief. Later that evening as we set the table together it took a moment for this sartorial commitment to register with my new friends. I remember one person remarking, “Oh! I thought it was an abstract design…now I see the sheep.” Another encouraged me to show Fernando García-Dory (Inland’s course leader), seemingly to imply he was both impressed by my commitment and that maybe I’d bring out a laugh for the team. My outfit itself could be described as cute, earnest, sweet—all adjectives that I hate when they are applied to me. I am a serious person, with little sense of humor, and particularly as a woman who often looks a decade younger than I actually am, I strive to be taken seriously. And yet…I dressed up.

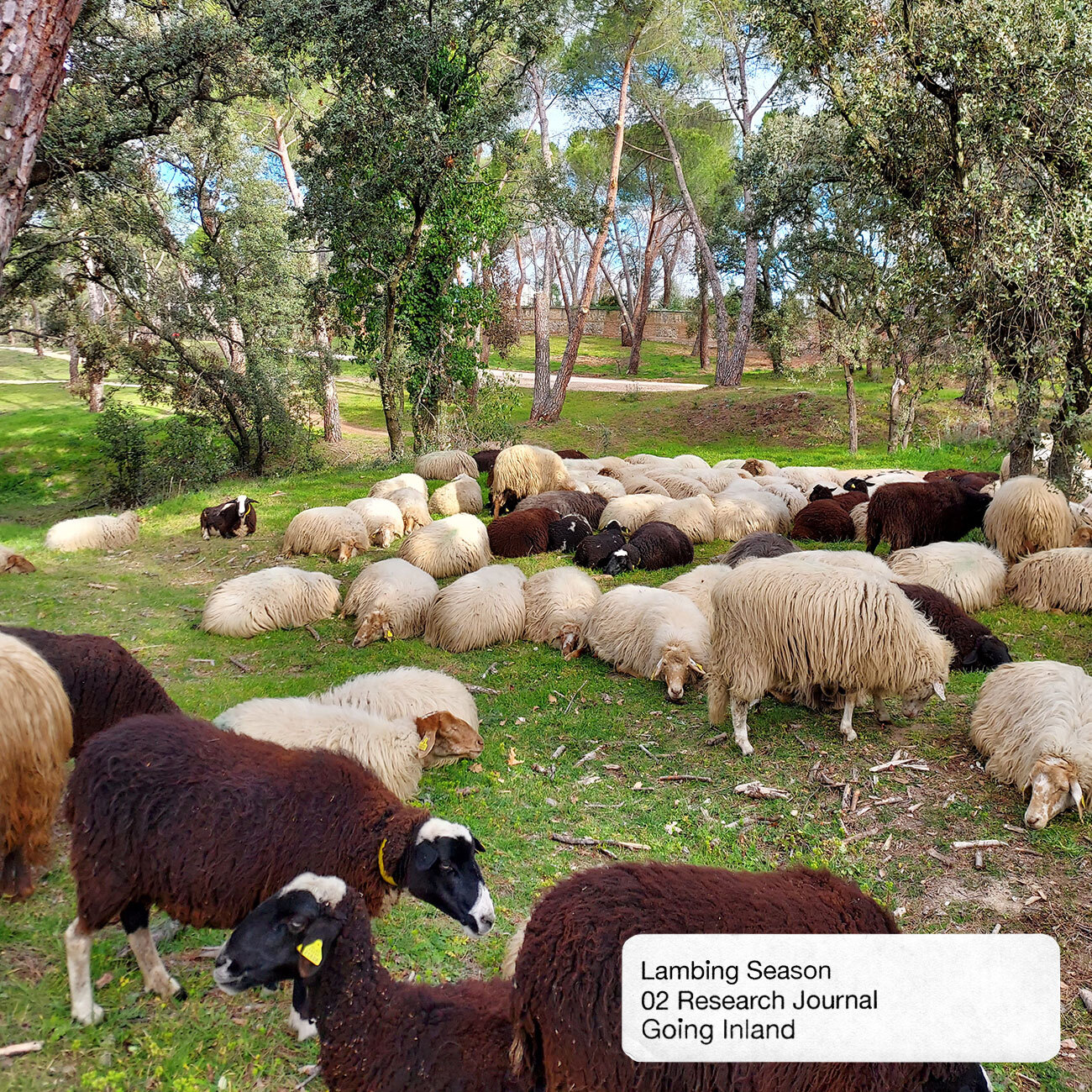

When we first approached the nursery at Casa de Campo I was already pumped with energy and expectation. It felt great to be outside and walking through the park, breathing in the fresh air as Fernando walked backwards, narrating our journey with historical details about the park’s opening to the public in 1931—centuries after being a pleasure park for royalty—and pointing out esparto grasses that are used to make espadrilles. Large umbrella pine trees dotted the park, their squiggly shapes reminding me of Dr. Seuss. As we moved further into the park we saw fewer joggers and fast-moving cyclists, and the clear paths gave way to sandy underbrush. Moving over a ridge we saw Sergio Montero Bravo’s nursery structure, something we’d read about in preparation for the visit. I strained my eyes, searching for the sheep.

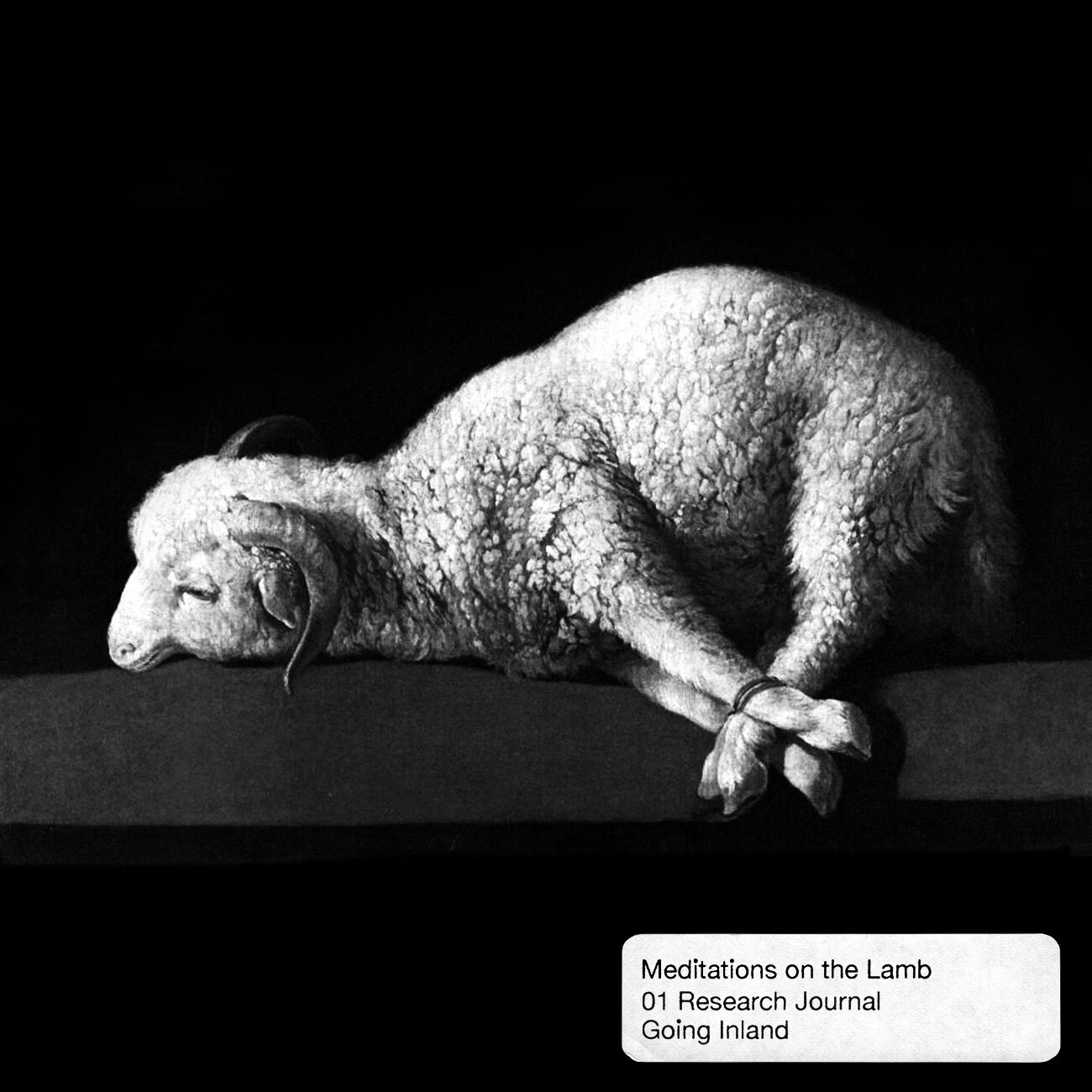

As we arrived I had to steel myself to stay with the group and not immediately head towards the small enclosure with lambs and their attendant mothers. The shepherd shared with us that the lambs had been born the night before, and their high-pitched bleating voices and wobbly legs confirmed their newborn, yearning status. Looking adoringly at the babies I kept thinking of the book The Little Lamb, which I read over and over again as a child. Searching for the title of this book online I found this YouTube reading of the book, and was comforted by its familiarity. The impressions the book’s pictures made in my mind were deep. When I think of sheep, these are the images that come to mind.

Later on, as more people began to drift over to the nursery, I allowed myself to walk over and take a closer look at the lambs. Their wool feels particularly sweet: fluffy, like a stuffed animal. I feel funny making that comparison, as if I know animals more through the books I read as a child—which almost always featured animals as anthropomorphized personalities—or through toys—soft stuffed animals or Beanie Babies. Is that why I was so excited to see the sheep—because they reminded me of my childhood?

Fernando shared with us a game that Inland developed to help children learn about shepherding, which involved wooden cut-outs of sheep and lambs, life-size dice, and large cube game pieces with weather patterns and wolves. He explained that when children came to visit Casa de Campo they were often so excited about the sheep that they immediately ran to the enclosure, clamoring to pet the animals. Seeking to shift the children from understanding their visit as an afternoon’s entertainment, they had groups play this game first to understand the complexity of shepherding and its relationship with the natural elements: rainy and sunny seasons, threats of wolves, and challenges in birthing lambs. Listening to him I reminded myself that it was good I was playing the game first too…perhaps I wasn’t much more advanced than the children.

After lunch we walked out to visit the herd, a flock of 300 or so sheep grazing across more distant parts of Casa de Campo. We could hear them before we could see them, their various bells blending with a chorus of bleating murmurs. Seeing them massed together reminded me of an ocean, the flock moving in synchrony with a kind of externalized hivemind, albeit one guided faithfully by a sheep dog and helped along by a mastiff. I didn’t want to be the antsy child at the petting zoo, but I had a deep desire to pet the sheep, or even hug them. I looked back and forth at my peers, about half of which stood atop a ridge to observe the flock, and others of which stood closer to me, inching towards the sheep. Hesitantly, I walked over to the shepherd and asked if I could touch the sheep. The shepherd told me that it was OK, but only if they came to me first. The shepherd encouraged me to watch the direction the sheep were slowly moving, and to sit down in front of them so that as they mowed their way through the undergrowth they’d come near me.

I knelt down and nearly instantly was surrounded by sheep. Some were blatantly uninterested in me, the latest obstacle in their path to keep eating. One was quite curious though, and started to nuzzle me and lick my coat. I touched its soft, burly wool and started to talk to it, saying hello and apologizing that my clothing wasn’t food, and probably wasn’t too tasty. Seated on the ground, the sheep and I were at eye level, and I watched it closely as it nudged its wet nose against my shoulder. It was a beautiful animal with a butterscotch brindle pattern and thick wooly coat. Putting my arm around it I could feel it breathing in and out beneath its soft fur speckled with dirt and collected burrs.

They connected on a fundamental level to another entity, beyond the borders of language or social custom. They were humbled.

I thought about taking a picture. My landlords, bemused by my participation in the program, had encouraged me to send photos. I knew my boyfriend and my family were eager to see what I was doing, and would be happy to see that I was so happy. At the same time, I was wary of minimizing the experience by focusing more on capturing it in photographs than soaking it in. In one of our first discussions, Fernando had talked disdainfully about the Disneyfication that recast the countryside of Spain as bucolic backdrops for peasant fantasies, with tour guides dressing up as shepherds and walking visitors through the hills.

I was loath to be that derided, self-absorbed tourist, and yet I wanted some photos to share what I was feeling and to remember it. I took three selfies. I couldn’t bring myself to take more—both because it felt bad and because I’m terrible at taking them. In the photos I am exuberant. My smile is wide and it’s as if you can hear me saying: Hello! This is so awesome! as my voice lilts up at the end of each exclamation mark. The sheep, whose face is visible in profile, looks at the camera, as if in on the fun and angling to show off her best side.

I lost track of how much time we spent with the herd. I alternated between inserting myself in the middle of the flock and walking to its edge to talk with the shepherd. He showed me how the mothers closest to giving birth rested on the ground, panting with bulging abdomens and full udders. At one point he called us all over, certain that a mother was about to give birth. I was seized with emotion and rushed over— pushing up my sleeves, as if I would be ready to help. Ultimately though it was false contractions, and eventually the sheep mulled over to the rest of the herd, and they all slowly moved on. Eventually, our group gathered up and we started the long hike back to the train station at the edge of Casa de Campo. I felt quiet, tired but sated from a day outside and the rush of endorphins.

Writing this piece, I’ve moved through these emotions again and have wondered: Will I be self-conscious about my self-consciousness? Is my confusion about my happiness an internalized patriarchal disdain for emotion? Or is my embarrassment a subscious anxiety about my lack of connection to the natural world? And more broadly, why did I feel that my joy was something I needed to suppress?

Ultimately, I worry that my happiness sets me apart as someone for whom being with sheep is extraordinary. I had to look up what biodynamic farming was after our first dinner together, and I only volunteered in the garden a few times last summer. I am someone who works in an organization and I am a curator, both of which are roles that Inland has taught me to be wary and thoughtful of in different ways. Nonetheless, being with everyone in Madrid I felt a sense of purpose: deep down I felt that this is what I moved abroad for graduate school to experience. Inland has brought me joy, deep thinking, and friendship. I have love for it, and being part of it feels like a privilege, one that I sometimes wonder if I deserve.

I feel sheepish, which makes me laugh.

Talking with a friend from Inland, they remembered being with the sheep as primal and healing. They described getting up close to a sheep, feeling the exhales of their breathing and looking them in the eye. They connected on a fundamental level to another entity, beyond the borders of language or social custom. They were humbled.

My friend also reminded me that I was not the only person thrilled to be there. The shepherd who lived with the sheep day in and day out was just as excited to show us the sheep and point out those he had named. We had also met an older man that morning who, after coming across the enclosure in a walk in the park, had faithfully come back each day to help with the rearing of the sheep. Talking over dinner that evening, everyone in Inland Academy noted seeing the sheep was their highlight of the day.

My beaming joy was intense and maybe a little silly, but it wasn’t superficial. I think some of my anxiety in showing that feeling is because it makes me vulnerable. In a world where I am nearly always thinking about how to protect myself, connecting with another entity and feeling deeply—so much so that I can’t maintain my exterior as a serious, thoughtful, mature person—is a risk. That risk can be worth it though, as unnerving though it may be.