This story is a part of MOLD’s series on Decentralized Design. Through this series of conversations we explore how designers, thinkers, and artists are using decentralized approaches to seed a more resilient future.

I met Nifemi Marcus-Bello by chance in 2021. After living away from Lagos, I decided to return and rent an apartment in the city. I googled indigenous furniture designers and through internet magic I traced a gorgeous modern stool I saw in an article to Nifemi. He delivered my order himself (2 stools, 2 lamps!), and since then we’ve been kicking it. Bad man Nif is what I call him. He’s a “bad man” in the best sense. Nifemi is a well awarded designer whose practice is distinctly Nigerian, specifically of urban Lagos. His design language also translates universally, whether by strategy or instinct: his pieces can (and often do) occupy multiple and diverse social, cultural and geographic spaces. Maybe that is another expression of modernity, to be comfortable everywhere. In at least this sense then Nifemi’s work is modern.

In his Africa – A Designer’s Utopia project, Nifemi is currently researching what he terms “anonymously designed objects” in Africa. The research project showcases the ingenuity of, hitherto misqualified, design solutions unique to the urban landscape of the continent.

All Hail Bad Man NIF

– Tunde Wey

Tunde Wey:

I wanted to start talking about something you and I have talked a bit about previously in our personal relationship — with money. What’s your relationship with money, do you feel like it’s a good or bad thing for your design process?

Nifemi Marcus-Bello:

It’s funny. I have a very funny relationship with money because I’ve had it and I haven’t had it. [laughs] So for me, my own relationship with money is something that’s always at the back of my mind. I feel like a lot of designers shy away from money and having conversations around money. They feel like it’s something that shouldn’t be spoken about because it might affect the flow of creativity. But for me, I actually think it helps and improves creativity [laughs]. You don’t have to think about the constraints of not having money, even though a lot of good design is birthed from the constraints of not having money.

TW:

Story, story. You know in a lot of your interviews and in our conversations constraint comes up a lot. So I wanted to ask you this question about constraint and money — how much money do you have in your bank right now?

NMB:

Which account? [laughs]

TW:

That was a trick question. But I am interested in knowing how you think your work might change if you have money, and what your designs could look like once you don’t have any personal constraints and it shifts more to technical constraints.

NMB:

I don’t think it would. Because for me, I think that a lot of innately being African and being born on the continent is being very contextual in our approach. Whatever is around us we make use of and we create. Finding a way to create opportunities around what is around us is a uniquely African way of thinking. For example, look at Ghanaian [design], where they are using gold to create chairs for Ghanaian royalty because that’s the material that’s readily available in their region. You might see it as luxury, but that’s availability. Same thing with the bronze I currently work with, it’s because [in Nigeria] there are so many bronze casters here who have a culture of creating objects and artifacts. So for me, African design is heavily contextual—it’s what a place means to a material or even to a people.

TW:

In your work I’ve seen you use a lot of wood and steel, and now I know you’re working more with bronze. But I’m interested in your opinions on plastic.

NMB:

Plastic is really interesting, because I think if used well it can work to our benefit. It’s like the evil material of the 21st century, but that’s because all of these products are poorly designed because often designers don’t think of the [life] cycle of the product. The thing about plastic usage in Nigeria is that 90% of it is recycled one way or the other and a lot of the products I’ve looked at in my research are upcycled. It really opened up my mind because we have huge recycling habits and culture, right? Like our moms will go buy ice cream in a plastic container and once the ice cream is done, they do all sorts of crazy things with the ice cream container. So you might get a surprise when you go to the freezer and find it’s been storing soup all this while.

For me, African design is heavily contextual—it’s what a place means to a material or even to a people.

TW:

That’s the worst thing, because palm oil stains [the white containers].

What you’re saying makes sense, but when I think about plastic I think about convenience and also how Lagos has in some ways really become a dumping site for these products. And in that context it makes me question this pragmatism, because the African or Nigerian negotiation of a context is really things that have been imported to us and dumped on us, leaving us to conform to that reality. So when you think about your design philosophy as a designer that tries to maximize materials in a particular context, do you think about how that context was created and how that might be limiting?

NMB:

I have asked myself that question, and again. Especially in this research [with AADU], where I am asking things like: Why do these materials exist here? Why do these forms exist here? Who’s dictating or creating these opportunities for these products to exist? And how is it affecting the way we are living our day to day lives? And then, how is it affecting urban planning and urban expansion? Getting to the heart of things like, why [in Lagos] we have to be considerate to putting water storage on your roof, why a great deal of houses have a tap outside where these Meruwa guys fetch water? So I won’t lie to you, I don’t have the answer to that yet. But that’s why I’m carrying out this research because I’m trying to understand what’s happening today with mass production and batch production of these products.

TW:

Right so, tell me about the project that you are researching now.

NMB:

So I’m looking at anonymously designed objects and how they integrate into the urban landscape of major cities across Africa, starting with Lagos.

TW:

What are some examples of the objects you are looking at?

NMB:

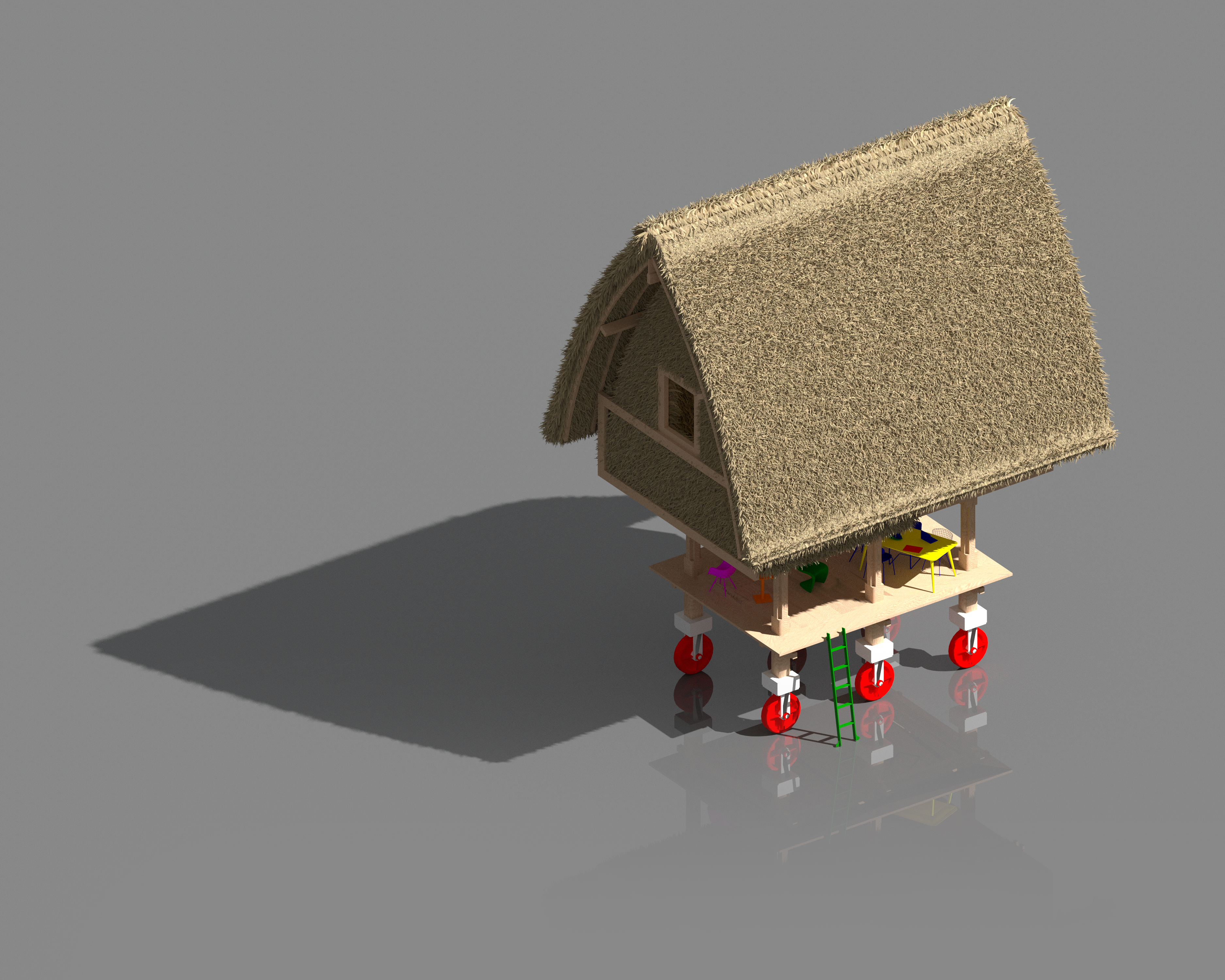

So I’ll give you two examples. The first product I’m looking at is actually a product called Kwali which is a portable convenience store that is used to sell confections in traffic. To me, these products are extremely well designed, and it creates job opportunities for people while making their lives economically viable.

TW:

That makes sense, but I have a challenge to your design philosophy. Take for example, the prison shank. I think that’s a well-designed product, right? It has a sharp tip, there is sometimes even fabric around the handle that you can attach around your wrist. That’s an example of fantastic design for products that are horrible, right? And when we start talking about the constraints of living in Lagos and people having to make their livelihood by selling shit on the road in these portable convenience stores, I’m more interested in why that dude has to do that than how well the solution he comes up with works. Like the design might be interesting, but I don’t know if it’s necessarily good design because the circumstances are terrible in my mind.

NMB:

True, for me I think when it comes to products you have to kind of place them in an out of body experience. For example, I recently had a conversation with someone where I said that if someone was going to give me a brief to design a kiosk for Coachella, I would redesign the kwali and it would work effectively. Everything you need, food, water, drugs [laughs], you could sell from a kwali, and of course it would be well-branded. And of course, what’s going to happen, as with what happens with all things on the continent is that someone is going to document, redesign it and sell it. And then we’re gonna be like, “Ah, but that’s what we used to do.”

Things have never been perfect, but as Africans we always create. Another thing I’m researching is those houses in Surulere where they have the security guards who have cut out small windows in the walls [of the houses they guard] so they can sell things. People might say because they are defacing the building, it’s bad design. But to me, that’s an architectural archetype that solves the problem so that the security guard can just sit there and create extra income. So for me, regardless of what it is, if it’s sad, whatever, we don’t sit back. [As Africans] we conform and create.

TW:

I’m impressed by your pragmatism. This points back to your point about bad urban design. I think that part of the problem is that we have so much ad hoc design. And when you cobble this ad hoc design together it creates something that is sometimes not navigable. So on one hand you’re solving problems as they come up, but when you look at the aggregate, you actually end up with an even bigger problem to solve. What do you think about that?

NMB:

Ultimately you can’t move forward without good governance and policies in place. Design is political. I think the reason that design doesn’t really have a “face” on the continent is because there are no policies or politics that allow for design to be placed at the forefront. In terms of design I’m not just talking about products, but urban planning, education, and healthcare. What’s beautiful about these products that I’m looking at is that they are like a “fuck you” to the status quo. We can’t just sit back and wait, we’re going to try to solve the problems that are right in front of us through creativity.

TW:

Right, so what is the second object you’re looking at?

NMB:

So the second object is Meruwa, which is a wheelbarrow-like device that’s used to transport water from one suburb to the other.

This interest came about during the pandemic when I was doing research for a handwashing station I designed with the community. We designed this handwashing station because during the pandemic a lot of artisans I was working with were out of work and were looking to create something useful. So what I did was talk to friends who were doctors and nurses to figure out what problems might be solved through better design and realized there was a need for handwashing stations. I quickly realized while speaking with both artisan and medical practitioner stakeholders that we needed to create something that was local and had a contextual design language, which made us factor in the Meruwa water hawkers who were bringing in the water to these hospitals.

Design-wise we wanted to create a form that people were visually accustomed to, while also factoring ease and efficiency for the Meruwa who were providing water. So the handwashing station was designed so that instead of pouring water into the hand washing station, all they would have to do is replace the existing empty 25 liter keg at the bottom with a different keg that they brought in.

TW:

Right, so the Meruwa push this wheelbarrow that has usually six 25 liter kegs from house to house for people who don’t have running water, it’s really about portable convenience for them. With this new research project are you researching the design of these products and then redesigning them?

NMB:

I’m not redesigning them. Why redesign if they work? I’m actually trying to learn from them, to see how they’ve used materials and material ability to dictate forms and create solutions. One of the things I hope to achieve with this research is to create an open source resource so that this information is available to future designers. [African] design language is different from the standardized design language of say Europe or North America, but I think it’s important to build an archive of products and ideas that embrace how we live, rather than dictating how we should want to live.

TW:

Right, I have a story that sort of illustrates that. Where I live there’s a woman that makes akara on a side street. Her daughter will take this akara, put it in plastic containers along with ogi and put it on her head and sell it from there. So once, I asked her if she would like me to make one of those NesCafe coffee pushcarts for her so she could just scoop the akara and ogi from there and sell it. But she said no, that doesn’t work for me, what I do is better. I wanted to get your opinion on that from a design perspective, because to me it’s less efficient, but it’s pretty characteristic of Lagos.

NMB:

Good design is like the cornerstone of good ethnographic research. From her point of view, too drastic of a change is the same as shooting yourself in the foot. Her customers might have it ingrained in their head that the best akara comes from a vendor that sells from their head, and would refuse to buy it from the cart.

This is why I think those design sprints they’ve introduced in design thinking are so funny. You can’t create anything with just two months in the field, you have to be ingrained in that community. Humility is important in design, not just from your own point of view but also the product you are trying to create. You have to think about the person, material, the usage, the emotional context and connectivity.

TW:

A lot of the furniture you design is unconventional and unexpected, something that grows with you over time. I’m interested in understanding what is beautiful and what is ugly to you in design?

NMB:

This is a really hard question because I don’t often think of ugliness. As for beauty, I think that really lies in honesty. I like the juxtaposition of materials, and also using materials in unexpected ways. There’s a Dieter Rams saying that design should be unobtrusive. But for me, the design in Africa can be obtrusive, it can be sculptural but at the same time extremely functional. So before, I was really interested in making design that fit seamlessly into the background, and sometimes I still design like that, but now I’m becoming more comfortable with creating things that have presence.