This story is a part of MOLD’s series on Decentralized Design. Through this series of conversations we explore how designers, thinkers, and artists are using decentralized approaches to seed a more resilient future.

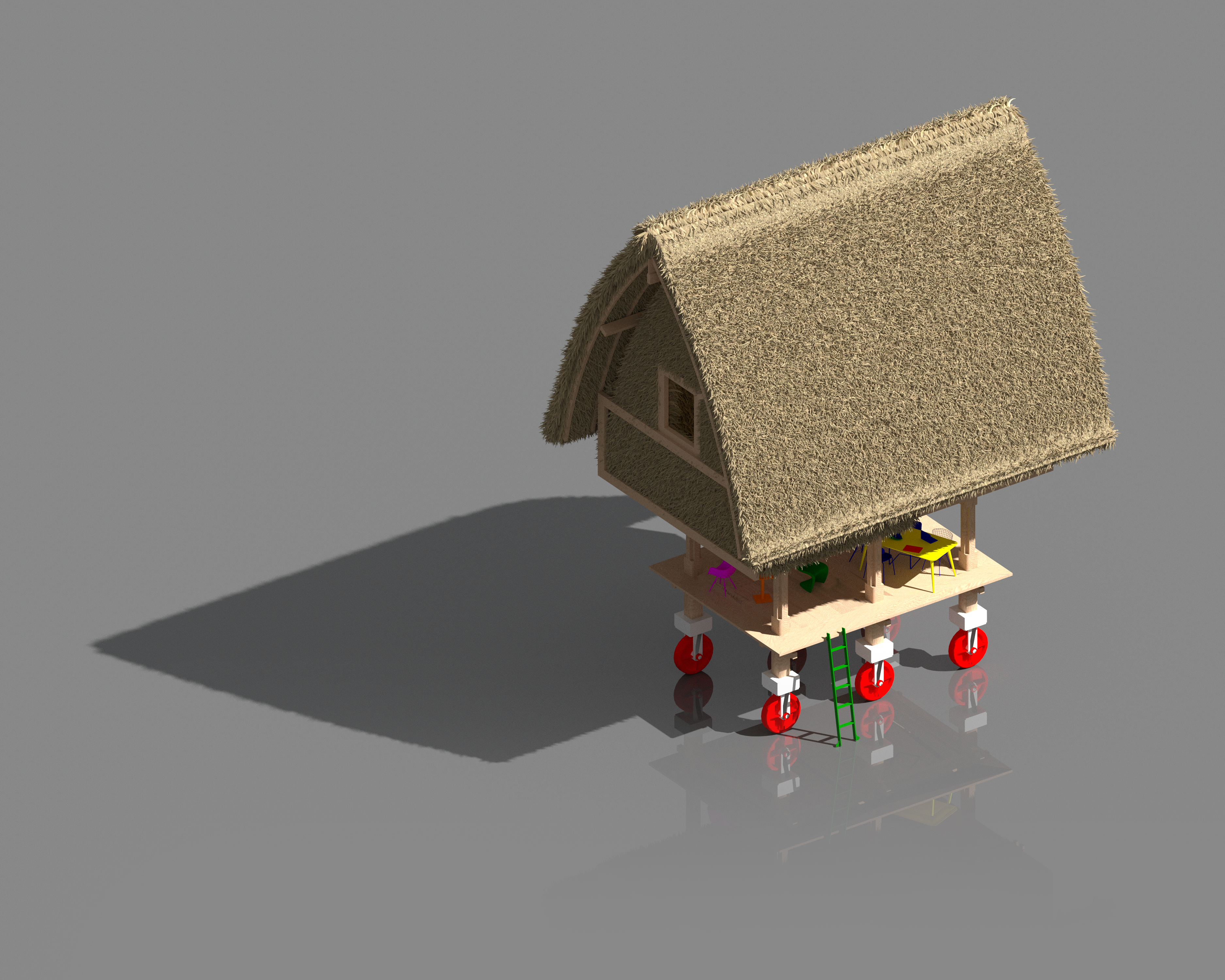

For many working outside of Southeast Asia, one’s first encounter with the term lumbung came courtesy of ruangrupa, the Jakarta-based artist collective and artistic directors of documenta fifteen which ran for 100 days (from June through September, 2022) in Kassel, Germany. The direct translation of the term is “rice barn,” an agricultural architecture “where harvest surplus of farmers is stored for common good.” But used within vernacular Indonesian, it is understood to mean an opportunity to share resources collectively. Through a curatorial cycle that began before, but then ran through the pandemic, ruangrupa invited other artist collectives from around the world to participate and develop lumbung together. ruangrupa’s statement from June 18, 2020—at the height of the global pandemic—explains:

Each of the lumbung-members will contribute to and receive diverse resources, such as time, space, money, knowledge, care, and art. We are extremely eager to work with and learn from other concepts and models of regeneration, education, and economy—other lumbungs practiced in different parts of the world.

Part of the programming for this edition of Documenta included virtual tours. In the last month of exhibition, MOLD Senior Editor Isabel Ling and I took the “Art, Food & Agriculture” virtual tour hosted by a Sobat (or friendly company—the term we used referring to exhibition docent) on zoom partnered with an exhibition guide on the ground who physically walked the group through parts of the exhibition. The tour left us with more questions than answers: What does it mean to be sustainable? What other agricultural models might provide blueprints for living and working collectively, outside of a rural context? How would an unruly artistic vision grounded in a model for resource sharing disrupt our notions of art making? We reached out to ruangrupa and received a generous response of time and insights from one of the collective members, farid rakun, who joined the collective in 2010. Below is an edited version of our conversation from early November, 2022.

-LinYee Yuan

Isabel Ling:

During our “Online Walks and Stories” virtual tour of documenta fifteen, we were struck by the use of lumbung as the guiding curatorial concept. How has the concept shifted for you, now that the hundred days have come to a close?

farid rakun:

Lumbung came from an agricultural tradition that is used across Indonesia. It’s in the vernacular: The government has used the term in different ways, shops call themselves lumbung, etc. The origin of the word is understood primarily as a rice granary.

We [ruangrupa] have played with the term since 2016 or 2017 as we experimented with the notion of a collective of collectives. ruangrupa was not the only collective [in Indonesia] at the time, there were others — mainly in Jakarta, mainly artistic as well. For us, lumbung is a shortcut—when we say lumbung, people instantly get that we are going to share something.

Through Gudskul — which is made up of ruangrupa, Serrum, and Grafis Huru Hara—we have made it a priority to practice as much transparency as possible—sharing skills, time, space, and of course money—between people like myself. It took several years to get to the transparency with which we now operate. So, while I initially started with ruangrupa, I can now do work for other collectives as well because of the partnerships we’ve created.

There are so many entities, from festivals to educational initiatives, in Gudskul. We are comprised of different legal structures of for-profit companies to non-profit foundations. ruangrupa itself is nonprofit, for example. Every one of us can look into each other’s bank account balance at the end of every month. We started sharing our bank account details in order to be fully transparent by the end of 2018, in preparation for when we planned on establishing Gudskul.

But that moment was also when the offer came from Documenta, asking if we would be interested in curating an edition of the festival. That’s when we decided to just keep doing what we were doing, so as not to be extracted to Europe. We responded by inviting Documenta to join us for the lumbung journey we were already on. The journey [of lumbung] was already in existence, but it has been enriched, or altered by the fact that documenta fifteen was part of it.

On the closing day (or maybe the day before) it became clear, at least for us, that documenta fifteen couldn’t continue participating in lumbung with us—it’s become too big. It grew, no, it exploded to become something else. lumbung has been taken on by others—artists have implemented lumbung in their own ways across the world from Germany, to Johannesburg, Bangladesh, Rotterdam, Vienna, and Amsterdam. [Lumbung] is not ours anymore. We remain informed through our relationships with these artists, but have not been involved in thinking of how these things will continue. We are taking time to regroup and see what the future of lumbung might look like from our end. It’s slow.

LinYee Yuan:

You mention total transparency, specifically when it comes to finances. Why is it so critical to the way you were thinking of facilitating a sense of shared resources, whether it was people, space or skills?

FR:

Transparency came to us when we were forming our practice because we knew everyone came from a different sensibility. One of the collectives, Serrum, was founded in 2003 to think about sustainability, or how to sustain one’s practice, differently. They found a sweet spot in the art ecosystem by opening a company for art handling. ruangrupa never did that, even though we started around the same time. We started with writing proposals, like a lot of artists.

Over time, the work becomes different and the sensibilities become different. But we still share the tax person, accountant, cashier, and rent. A lot of collectives in Indonesia start by renting a house, then turning it into something else. It’s still the model in different places in Indonesia. So, rent has eaten up 30% of our annual budget, so by combining these things, it’s better for everyone.

Last year funding from the Indonesian government became available again, but these fundings are competitive. In our ecosystem, there are other people and collectives that are younger than us [ruangrupa], who are not from the geographic centers—not from Bandung, not from Yogyakarta, or Jakarta—who are doing exciting stuff but not receiving the funding because of their location. That funding should go their way instead of our way. So then transparency is part of the survival strategy, it’s part of the sustainability discussion.Transparency is a consequence of it, let’s say.

LY:

To have this sense of vulnerability in transparency is so critical to the idea of sustainability, whether you’re talking about the sustainability of an organization or a movement or just our relationships in general.

FR:

We’re still dealing with that even after doing lumbung across three years of documenta fifteen. We are still thinking of models of existence.

IL:

What was it like scaling up your collective ideals to the international scale? How does the decentralization of lumbung alter that initial concept and what does it look like once it’s beyond just ruangrupa?

FR:

Creating something that went beyond our initial conception of lumbung was our intention, but it was also altered, so it’s not binary. COVID for example, happened. Our practice relies so much on person to person meetings, sharing food, sharing drink, sharing time, sharing mics, singing together, all that kind of stuff. 2020 changed our process. Like everyone else, we had to go through Zoom and it changed the planning of a lot of things. To let go was our intention to begin with. What we learned a lot about was the reception from the art world.

Because of the scale of documenta fifteen, if something went wrong, which, of course a lot of things went wrong, the art world looks for a person to be responsible. Then, they see our way of doing things as an irresponsible way of curatorship. For us, we tried our best to not play the role of artistic direction like the trope of the genius art director. That is all control. We always give away our control. Even in emergency meetings it was important to us not to be the one holding the mic all the time. We are trying to listen.

However, one consequence of this approach was that it became too big. 1500 people or more were part of the making of documenta fifteen. And then of course, we don’t know every one of them. I can say that personally, I’ve met only 10% of our collaborators in person. And then, the works featured in the festival themselves change all the time. For example, the open kitchen [staged by Gudskul] would cook things differently every day. And even the Cuban collective Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (Instar) made 10 different exhibitions during the 100 days. Due to its constantly changing nature we cannot have that much control.

For us, it was amazing. The way we want to do lumbung is not to create a global network that we claim control over or are solely in charge of leading the process. We don’t care about credit. We know we will never be able to know everything — our Indonesian passport prevents us from visiting many places in the world. Being able to work with people who work in their localities, something we call inter-local, instead of international, is what we hoped lumbung would be led by. And it was through this approach to lumbung that conflicts were taken care of in documenta fifteen.

LY:

So many of the collectives that you worked with are doing placemaking work in their own practices and in their own communities. Now that they’ve returned to their various inter-local contexts, I’m curious about the way that placemaking figures into thinking about creating more resilient models and systems that are responsive, and how they figure into a greater global capitalist impulse to scale everything up.

FR:

On an institutional level, small to medium in terms of scale makes the most sense because it’s agile, it’s flexible. Jumping to the conversation around placemaking, When we asked Frederikke Hansen, one of the artistic team members that worked intensively with us, what they expected from the people we were inviting, their reply was for these practices to keep on existing [beyond documenta fifteen]. So whatever the invited collaborator decided to bring to Kassel, the way we understood, was in itself a translation process. For example, for your magazine, you understand your ecosystem, you understand your contexts specifically, no? And then the question is how to translate that. I’m not talking about only geographical translation, but rather an understanding of context or local ecosystems, and then translating that to a physical thing in Kassel. For a lot of them like you said, this translation looked like placemaking, because it’s what they know.

A lot of our participating artists’ practices are rooted, grounded in soil, let’s say. Whether it’s in Hanoi or in Dhaka, they’re rooted in that place. The main question is how these artists could use the opportunity to be part of an edition of documenta and to translate their work in Kassel to be of use back home. Although, in the end, our collective and its operations are still being extracted to the West, we hoped that our work in Kassel and in documenta fifteen would be able to feed back to Gudskul in Jakarta. Gudskul got the implications and consequences, but also the benefits of ruangrupa’s position at documenta fifteen. This geographic relationship is what we understood for ourselves and it is how we asked our collaborators to think about it. It is why placemaking is a consequence of this documenta fifteen.

A lot of people—including ourselves—turned to placemaking because that’s the strategy that they know best. We put the Gudskul kitchen behind the main venue of documenta fifteen in Fridericianum. We also put the dorm next to gudkitchen. In the end, it became the easiest place to experience and to understand what our concept [of lumbung] was. During the day it was a kitchen for artists and visitors. Every night, it became a life space. Sometimes it’s karaoke, sometimes it’s just eating. Sometimes it’s a party—different uses. But just by being there, people more easily understood lumbung—more than reading or walking through exhibition spaces. We have limitations, let’s say with words, with representations, with presentations, lectures and all that kind of stuff. We always come short. It’s so much easier if people come here and stay for a couple of days and be with us, and gudkitchen is such a shortcut. That has been useful.

LY:

What was the thing that you felt like people would understand when they experienced this kind of communal meal or event at the gudkitchen?

FR:

Openness, I think, including patience. Eating and gathering. It’s a practice. It’s an action. It’s being there and being present. You cannot fully design everything. You cannot say this person who’s sitting next to this person eating this and drinking this will feel this way or think this way. No, you just have to be in that setting and be positive. Being a host is very important for us. From our side, that was one of the most grueling and energy consuming parts of documenta fifteen.

That’s why we didn’t know what it was actually going to be. We didn’t know that it was going to work as a karaoke place. It really turned out to be a perfect setting for karaoke, with the walls and tents. But it was not fully intentional. I come from an architecture background. It’s very different than the architectural approach where one architect decides on everything.

IL:

Now that you’ve come to the end of the documenta fifteen journey, as you said, ruangrupa continues — the collective and the work continues. So what’s next for your collective?

FR:

One priority is the sustainability of Gudskul, because we are still [financially] precarious. So one answer was to do a homecoming for Gudskul. Because Gudskul was part of documenta fifteen, at least 1.5 years were taken from its development. We’re taking a break from our regular yearly program, which focuses on education, collective and ecosystem building. Instead, this year, every one of us has to think more, to really commit to things that need commitment in our own lives—for myself, I’ll be a stay at home dad for a bit.

For us, there are two levels. One is to make Gudskul another thing from what exists in the West, to be separate from other centers of contemporary art, either New York, London, Berlin, you name it, even Singapore who’s trying their best to be a center. Right now I think there is an interest in collectives and how to practice it. Instead of us being invited somewhere else to share our knowledge, we should be able to invite those who are interested here to Jakarta, where we are and where we work.

Secondly, but also relating to Gudskul’s role in Indonesia or Southeast Asia, we should not ask people from different islands of Indonesia to come to us in Jakarta. We are only starting to see whether this new method will work or not. Some people have been interested in coming to Gudskul to collaborate with us, generously sharing what they have with us. But we’re trying to extend it, by not having this exchange in Jakarta, but to go to Sumatra, do it in Makkasar, do it in Papua, even. We want to practice what we have been preaching. The way we share is spatial, it informs our resources, history, knowledge and visibility. So let’s bring it somewhere else.

In Jakarta, it feels almost oversaturated. It’s much more useful if we are also going to other places in Indonesia. We know firsthand why we do this, why we do Gudskul. We know why it’s important as people from Jakarta or from the island of Java to understand how we are seen as colonizers by people from the east of Indonesia or from people from other parts of Indonesia who have different experiences in terms of being darker skinned or being less resourced by our national government. It’s also important to talk about our colonial past in the international art scene. Someone in Jakarta talking about Papua is just a repeat of someone from Europe talking about their ex-colonies. We’re not interested in talking for Papua and we don’t have the capacity to do so, anyway.