This piece is a part of our series Earthseed, which explores Parable of the Sower’s legacy in shaping our current attitudes toward food futures.

It isn’t enough for us to just survive, limping along, playing business as usual while things get worse and worse… there has to be more that we can do, a better destiny that we can shape. Another place. Another way. Something! – Parable of the Sower

When preparing for future disasters, it’s important to specify what you are anticipating.

Is it a global disaster? If so, is it climate-related? Is it war? Is it a pandemic? Or is it all those things?1

Are you trying to survive? Or are you trying to rebuild?

Alone? In a group? A community?

What is important to pack?

Do you imagine a fancy bunker? Camping in a public space?

Does modern currency still hold value? How will you trade?

What dangers exist?

Do new freedoms emerge?

And above all, how and what do you eat?

- 1. Because we all know these wrap and swirl into one.

In many ways, creating an action plan in case of disaster is an exercise in fictional world-building. Preppers, survivalists, speculative designers and sci-fi writers are all futurists, imagining another world in which the systems we have today are either deeply changed or non-existent.

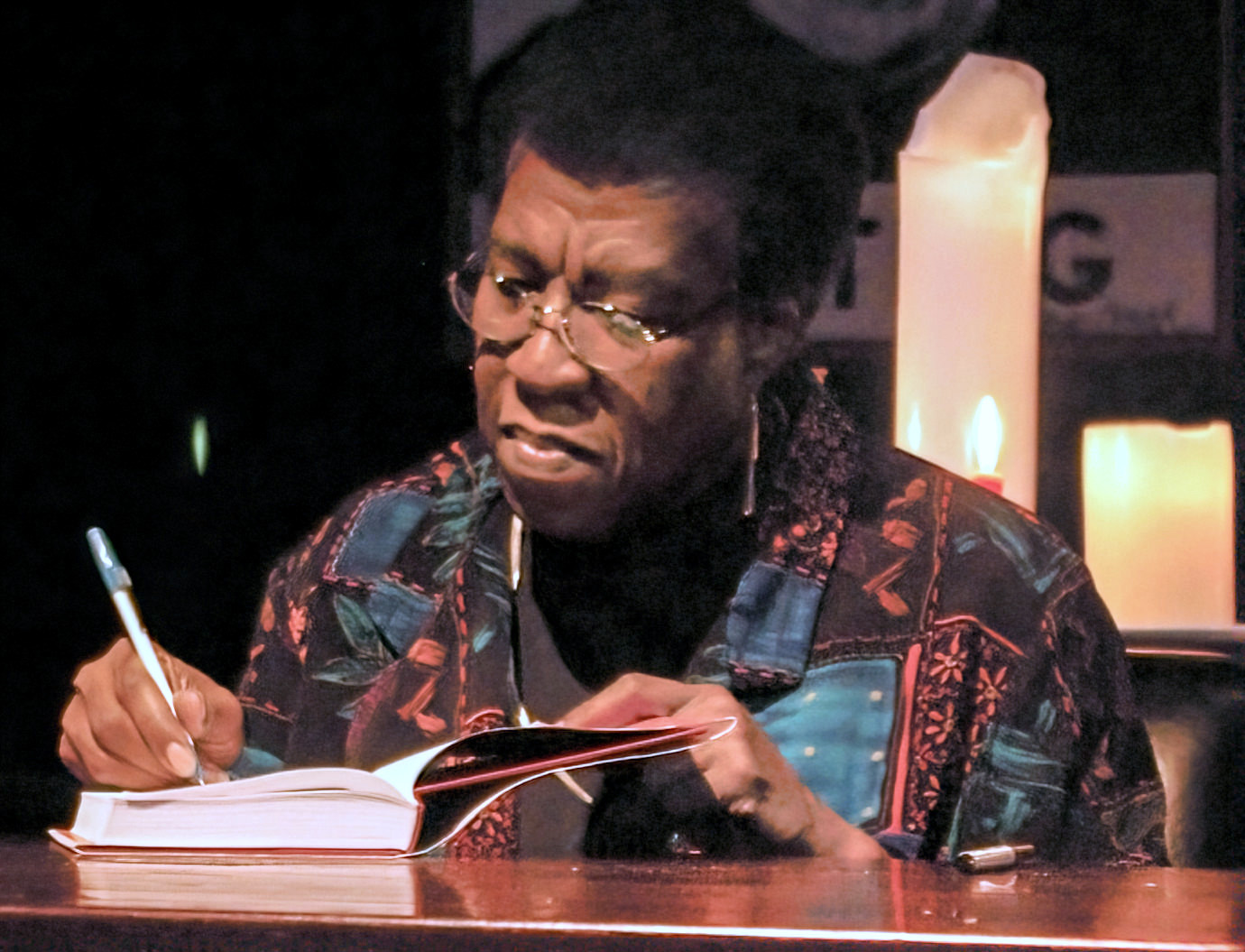

When choosing what to gather, the protagonist of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Lauren Olamina packs: canteens, pots, dried fruit, money, rope, flour, and seeds. She writes: “It isn’t enough for us to just survive, limping along, playing business as usual while things get worse and worse… there has to be more that we can do, a better destiny that we can shape. Another place. Another way. Something!” She is preparing to survive and to rebuild. And she is imagining she will be with others.

Set to begin in July 2024, we are currently fully immersed in the prophetic timeline Octavia Butler set for Parable of the Sower. At the end of the book we learn which seeds she has stored and protected over the years: “Corn, peppers, sunflowers, eggplants, melons, tomatoes, beans, squash…peas, carrots, cabbage, broccoli, winter squash, onions, asparagus, herbs, several types of greens.” Her stash also extends to tree seeds: “Oak, citrus, peach, pear, nectarine, almond, walnut, and a few others.” As Lauren says, “They won’t do us any good for a few years but they are a hell of an investment in the future.”

The future I imagine is inspired by her spirit. It is a future where we grow and flourish alongside one another, making our contribution to the wider ecological systems we’re part of. In response to this book and as part of research into seed-keeping techniques and economies, I designed and made a series of wearable seed libraries—glass necklaces filled with a garden’s worth of vegetable and herb seeds to be protected and planted if needed. “Break in case of emergency,” I told people wearing them. Part apocalyptic speculative design, and part practical, they are oriented by our unavoidable need to feed ourselves and others. These wearable libraries integrate the humanity-old practice of seed-keeping into our everyday lives and strengthen the potential for food sovereignty.

Seed-keeping is part of our choreography with plants, soil, and with food: from the highly engineered Arctic Svalbard seed vault, to the practice of migrating people sewing seeds into scarves, to enslaved people hiding seeds in their hair, to farmers selecting seeds from their top crops. Seeds adapt to their environments and through our tastes. Sibling tomato plants from the same parent seed will produce seeds with dramatically different properties depending on where they are planted. Due to the privatization of genetic information, vulnerabilities such as floods at institutes like Svalbard, and the way seeds adapt to unique environmental factors, it is increasingly important that we all engage in seed-keeping and create decentralized seed libraries filled with plants that are relevant to our local climates, soils, and cultures. Seeds are simultaneously a link to the past and an anchor into the future. They deserve care, reverence, and intimacy.

As part of her religion Earthseed- the Book of the Living, Lauren Olamina writes:

“A tree

Cannot grow

In its parents’ shadows.”

This time reading these words, they changed for me. As soon as I opened the book I was reminded of the deep relationship Lauren has with her dad. With a sinking stomach, I also remembered that he disappears. Two weeks ago my own father essentially disappeared. He died suddenly and without warning. In good health, without sickness, without accident, a fluke brain aneurysm in the middle of life, full life, while he was making himself coffee on the small wooden sailboat he was living on. In the novel, Lauren’s dad doesn’t vanish until November 2026 and his violent and controlling tendencies are nothing like the joyful, creative sensitivity of my own father, but the feeling of him dropping off the side of the planet is eerily resonant. The feeling of someone who was always more prepared and more capable, someone who has survived some of the riskiest situations—an anchor—suddenly passing the torch without warning and without time to prepare.

The Parables by Octavia Butler always appear to me right when I need them. It is a gift to revisit an idea that now, with the changes of life, has new resonance. “God is change,” Lauren always repeats.

A sculptor, an expert fabricator, and a sailor, I had never seen my dad plant seeds, but this spring with the help of his friends, he started to plant food. He planted in raised beds he had built in a defunct little dingy. Resourceful and playful as always. The last day I spent with my dad he proudly harvested the first eggplant, his favorite vegetable, he had ever grown. We marveled at the beauty of the flowers on the plant. Neither of us had ever seen one and it was pure delight. His smile took up his entire face as he grilled it and served it alongside a big batch of pasta alla norma to a full dinner table. When I went back to his garden after he passed, it was full. With more than enough food for many dinners and even some extra for local animals. He was preparing to feed us. We do not always reap the harvest of all the seeds we sow.

I immediately thought of Lauren Olamina saying seeds “are a hell of an investment in the future.” It might be true that “a tree cannot grow in its parents’ shadow” but it is also true that all trees grow in community. And, when a tree dies, it gives its nutrients to those organisms around it.

Octavia wrote in her journal the directive to “…Make people feel, feel, feel!” In fact, her words conjured an even bigger power: they invoke a response. I am part of a large cohort of people who are creating in response to her worlds, echoing her, letting her ideas be seeds. Since the first wearable seed libraries, I have continued to make seed libraries and run seed-keeping workshops. However, beyond saving seeds, we need to plant them, and finding fertile ground is not simple, especially in urban spaces. In the future I desire, we plant orchards on our sidewalks and turn parking lots into food forests, we keep these seeds not just to survive but to have meals together. In the final chapter of Parable of the Sower, Lauren and her group decide it is time to take the risk of planting the seeds with the hope that something better might emerge.

Nobody plants seeds if they don’t believe they might be fruitful. Even trees sometimes resist fruiting when resources are low. Whether it is the physical seeds that we store, garden and eat, or the metaphorical seeds of Ocatvia’s words and lessons from my father, all seeds that enter the earth are planted with hope for the future.