Social Synergies investigates the social structures – both seen and unseen – that underpin food production and consumption

Biodiversity provides a social structure from the micro to the macro. Interlocked social systems can be found in land, water, and sky and can include microbiomes, insects, soil, forests, coral reefs, crops, livestock, and more. However, if biodiversity is a social system, then humans are one of the most antisocial species, disrupting forms, behaviours, and structures of the wider natural world with interventions like intensive, capitalist-driven agriculture. The key to a future with a healthy planet, ecosystem and body lies in cooperation across all contexts — the social and ecological rhizomes, networks and communities that form our existing world.

Variety is essential to sustain life. Just as in social systems and organisations where diversity is key to success, the same goes for the natural world. It is just as the Myers-Briggs personality tests ‘proved’, that you need a collection of different types to make effective organisations and systems. The same concept applies to the natural world, and biodiverse ecosystems are essential for our survival. In the world of food, biodiversity has been decreasing over the years due to a number of factors, such as ecological engineering to modify genetics for ‘robust’ crops. Our shift from being hunter gatherers to settled agricultural societies created this shift. And now, a million species across the natural world face extinction due to our modified production and consumption behaviours.

Since the 1960s most of the world has transitioned to eating six major staples — wheat, soy, rice, corn, soybean, palm/sunflower oil. This concentration of our diets has caused a shift in agricultural production away from local crops of different species with genetic diversity. Plants that fail to promise high profit— soft fruits such as damsons or quetsches, small leafy lovage, heirloom tomatoes, cardoons and angel beans — are slowly leaving our plates. This marks a loss not only for biodiversity, but also, our palates.

The designer, Fernando Laposse, highlights this loss in his Totomoxtle project, which comments on the lack of biodiversity in maize in Mexico. Laposse worked with indigenous communities to reintroduce diverse maize species that had decreased due to planting incentives that promoted certain varieties from the Mexican government. He took the work further by using the husks of the colorful varieties of corn to create a furniture veneer, which his partner communities were then also trained to create.

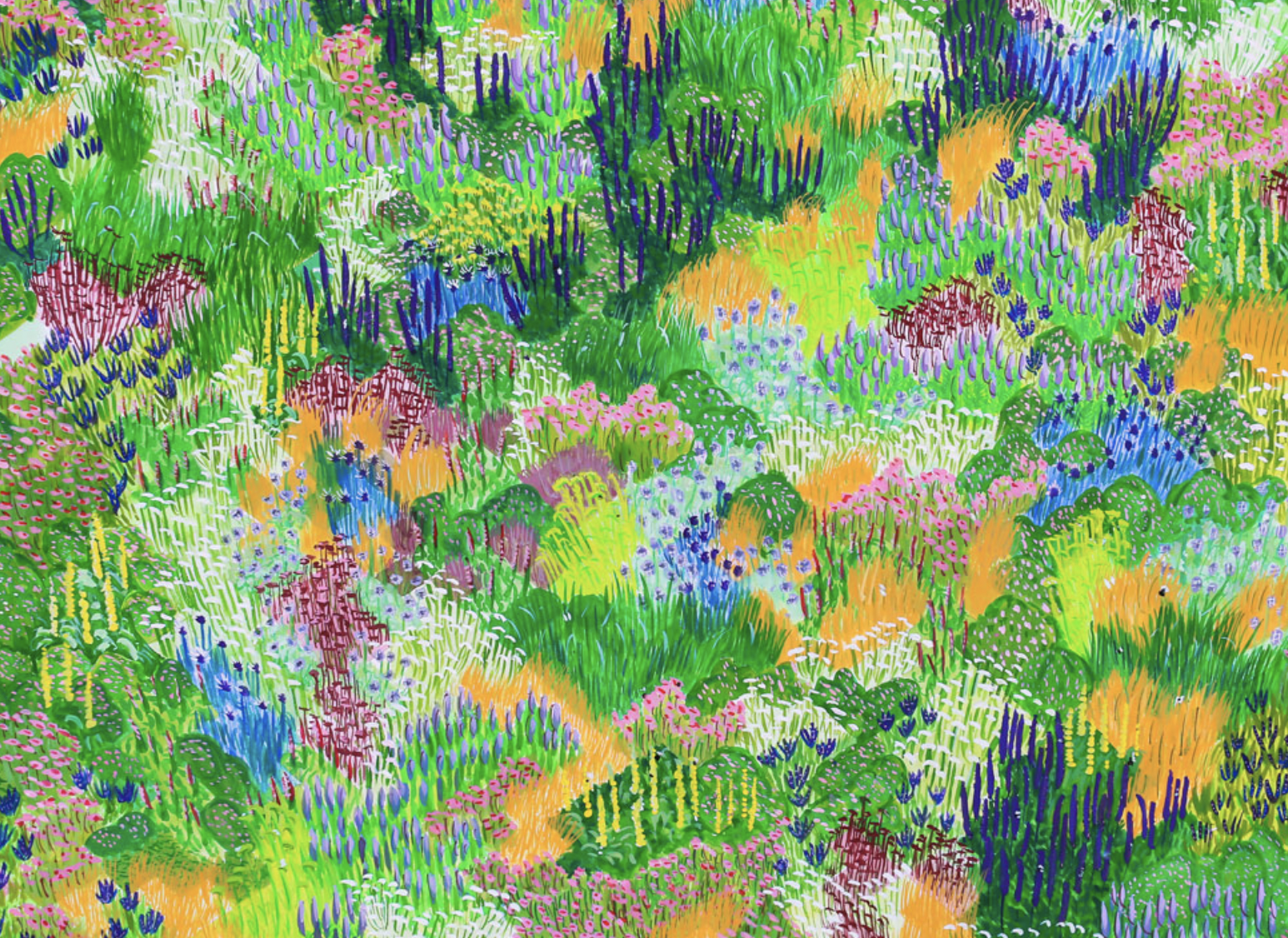

On a larger scale, UK-based artist, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s speculative project, Designing for the Sixth Extinction investigates how synthetic biology might influence biodiversity and subsequently climate change. If newly created species, made by synthetic biologists entered an ecosystem, could they support the regeneration of endangered species and genetic variants? Not only would the synthetic species promote healthy biodiversity, but they could also be designed to resist disease and even pollution. Ginsberg’s project builds off of the concept of re-wilding which reinstates natural processes in order to rebuild ecosystems—letting them go wild if you will. Ginsberg believes this concept can also be achieved with synthetic biology. Her current work with the Eden Project in the UK, optimises pollinating to help save the bee and insect population. To do so, Ginsberg has designed an algorithm to virtually map the series of plants in a garden that create the optimal environment for pollinator interaction. This algorithm – currently implemented at the natural space at the Eden project – allows visitors to generate the best palette of plants, colours and scents for their gardens in their own localities to promote biodiversity.

Another UK project, The Knepp Wildland, has been incorporating the concept of rewilding since 2002, on its 3,500-acre estate in West Sussex. The principles of its conservation were influenced by the Dutch ecologist, Frans Vera’s book Grazing Ecology and Forest History, which suggests that healthy, natural and biodiverse ecosystems of the past would have been influenced by grazing animals. Studies have shown that the waxing and waning of the grazing these animals do — as well as trampling grass and disturbing shrubs and trees — is essential to the wider balance of flora and fauna in the ecosystem. By reintroducing a natural variety of animals with different techniques of grazing as well as river restoration and wood pastures, each aspect has an impact on re-wilding and subsequently thriving biodiversity in the Knepp project.

It’s undeniable that changes in ecosystems have been, over the centuries, affected by colonialism and exploitation of local resources. Understanding the fall-out, however, requires a handle on how much we have lost already. Currently, the BioTime project, led by biodiversity pioneer, Anne Magurann, is keeping a live record of how the make-up of our natural world has changed over time. This global database of species and ecosystems allows scientists to track activity of biodiversity loss or gain, whose data contributes to conservation efforts. The database is searchable by species or biome, and includes records back to 1874 up to present day.

Previously the domain of environmental scientists and wildlife advocates, restoring biodiversity has been gaining mainstream traction.. The actor, Woody Harrelson’s Kiss the Ground film and project, spotlights regenerative agriculture, noting that “to cure our soil we need to change our food”. Even the former Apple designer Sir Jony Ive has gotten involved, pairing up with Prince Charles to address biodiversity and the climate crisis with the new Terra Carta Design Lab at the Royal College of Art in London. The Lab, a collaboration across science, art, design and engineering, aims to come up with real-world solutions to our loss of biodiversity. At the Design Academy Eindhoven, the designer Mario Minale is spearheading the Invisible Studio in hopes of inspiring a new generation of designers to come up with new ideas to support biodiversity, where “transdisciplinarity and biodiversity are [the] sources as well as our aims.” Biodiversity in the future will also be dependent on social systems in humanity working together such as with indigenous people, farmers, working classes as well as campaigners, scientists, and conservationists.

Awareness of biodiversity demonstrates a relationship with nature, a partnership that we can work in collaboration with. The monoculture that common agricultural practices have propagated is not sustainable – we need biodiversity and permaculture in our food systems, to support us when these monocultures fail. You can support biodiverse food systems by buying Fair Trade, whose fair prices allow farmers to reinvest resources to the cause; you can buy lesser-known varieties of food and grains at the farmers market, you can plant heirloom seeds in your fruit and vegetable patch, rewild – or advocate for a rewilding of – a patch of land. We need biodiverse organisms that flourish in symbiosis with others, we need forests that support the wood wide web, we need ecosystems in agriculture to flourish and be robust by their very nature of biodiversity. We need diverse societies like we need diverse natural environments, our very existence (and theirs), depends on it.