Like so many great things, Plant Fever transpired out of a conversation. In 2015, Laura Drouet and Olivier Lacrouts—the curatorial duo behind D-O-T-S—began chatting with Dossofiorito, a botanically adventurous design studio. They talked about plant diversity, and how objects could play to plants’ distinctive particularities. “This is now defined as multi-species design, when you do not consider only the needs of human beings, but also other species—so animals, or in this specific case, of plants,” says Lacrouts. Drouet adds, “The fact that they were looking at it from the perspective of trying to feel like plants, to be like plants, and look at the world like plants, and design accordingly, was a shift that was very profound for our practice.”

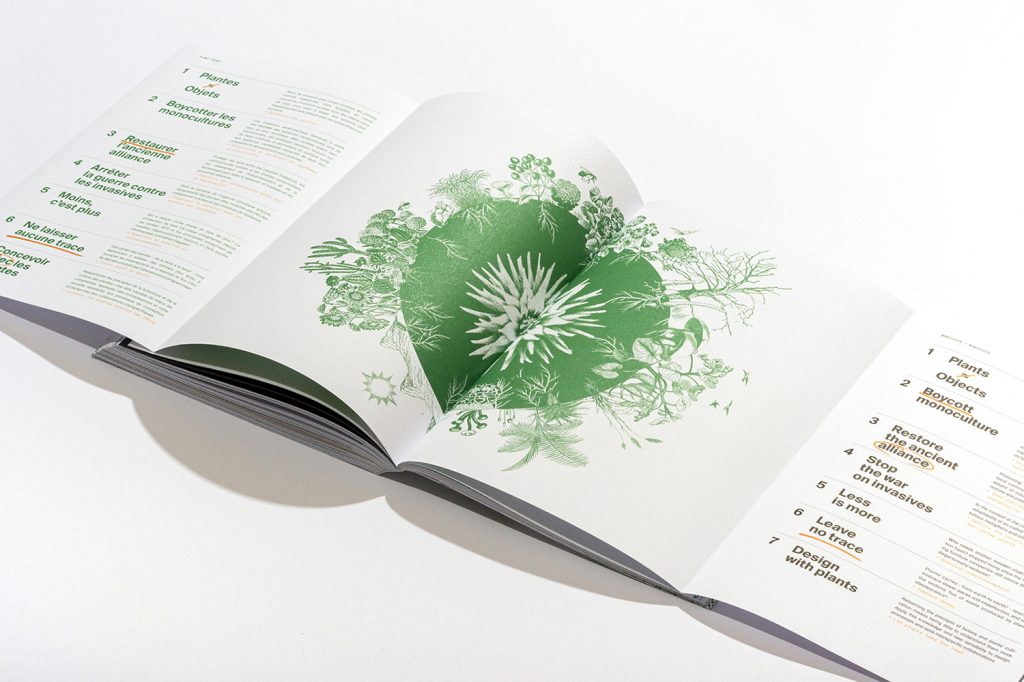

This simple yet “mind-opening” approach inspired Drouet and Lacrouts to seek out other designers who are thinking about the needs of plants. The upshot of their research has manifested as Plant Fever, an exhibition and book each teeming with vegetal-first concepts. We checked in with the curious twosome to learn more about their discoveries.

MOLD:

What were some of the concepts Dossofiorito were working on that really captured your attention?

D-O-T-S:

They designed a project for orchids. In the industrialized production of horticulture, orchids are put in pots and nobody really cares about their specificities. But they are epiphytes, so they grow without soil and can attach to other plants or whatever. And so Dossofiorito thought perhaps we should rethink the way we relate to them and start designing for them. They thought about a structure that would allow the plants to grow on it. It’s made of ceramic and full of water and the plants develop and grow roots to attach themselves to it because they can perceive the humidity of the water inside the pot.

It’s something very basic, but that was one of the first projects that we encountered that started shifting the perspective and started to think for plants first instead of thinking for humans and then for plants

MOLD:

Are there any far-out examples that push this way of thinking?

D-O-T-S:

We have sex toys for plants developed by designers [PSX Consultancy] that were questioning the fact that sometimes by displacing plants we take them away from their pollinators. If we take the example of Europe, we brought plants here from the Amazon forest, and these plants had pollinators which they don’t have here in Europe. It’s a very speculative project, but they devised some small accessories for these plants so they can [seduce and] reproduce.

MOLD:

Are the projects you highlight meant to provoke thought, or are some of them more practical?

D-O-T-S:

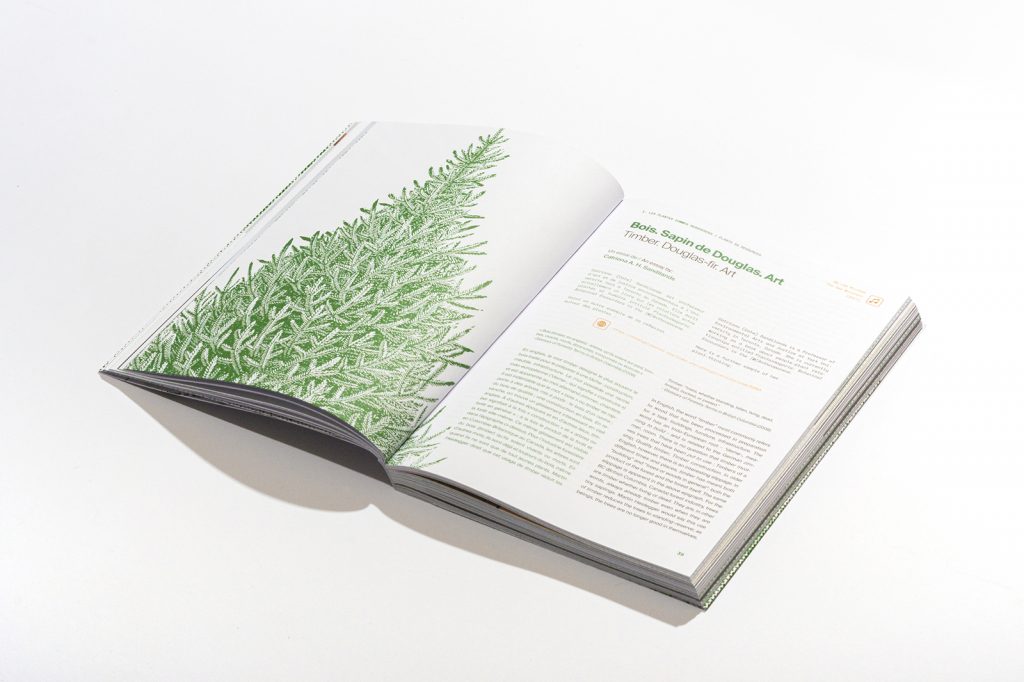

It’s really a learning path. We divided the exhibition into three chapters, and the first one is called “Plants as Resources.” There you learn about how we could use ephemeral materials based on plants—materials that can dissolve into the soil, for instance—instead of plastics, and how designers are tackling the issue of waste and monocultural production by using leftovers from pine trees or apple production to produce new materials. We also consider projects that try to revive the connections between humans and plants and landscapes.

MOLD:

There are a lot of cultures around the world that still rely heavily on plants as materials. Are there any projects that draw from indigenous principles, or ways plants have been used in the past?

D-O-T-S:

There are two projects in the first chapter that deal with Native people and knowledge about how to use plants in ancestral ways. One project, for example, is from the Mexican designer Fernando Laposse, who’s working on reviving these colorful, ancient varieties of maize in Mexico. He’s working with native populations from the Puebla state where the agrochemical company Monsanto introduced industrial corn that destroyed much of the knowledge that the population in that region had. Fernando is working to revive these ancient varieties of maize by using the husks in design—as marquetry, or veneered surfaces. By working with a group of local artists, he’s pushing people to rethink how they could use ancient varieties in new functions.

The second chapter is “Plants as Pets,” where we enter into the domestic environment. There we have objects or devices that are meant to spark a new curiosity towards plants—pots, music, and lighting appliances where the vegetal being is really complimenting the object itself. The idea was to show that a lot of designers are considering how to design devices that can enable millennials, in general, to interact with their home plants.

MOLD:

Does having them as pets, so to speak, then put them back into a position where we’re objectifying plants?

D-O-T-S:

It’s very paradoxical. First you have to start being aware of the plants. And so you have to see it and to bring it into your home and keep it captive, or domesticate it. And before you realize it, yeah, you have a problem because you’re keeping captive some living beings.

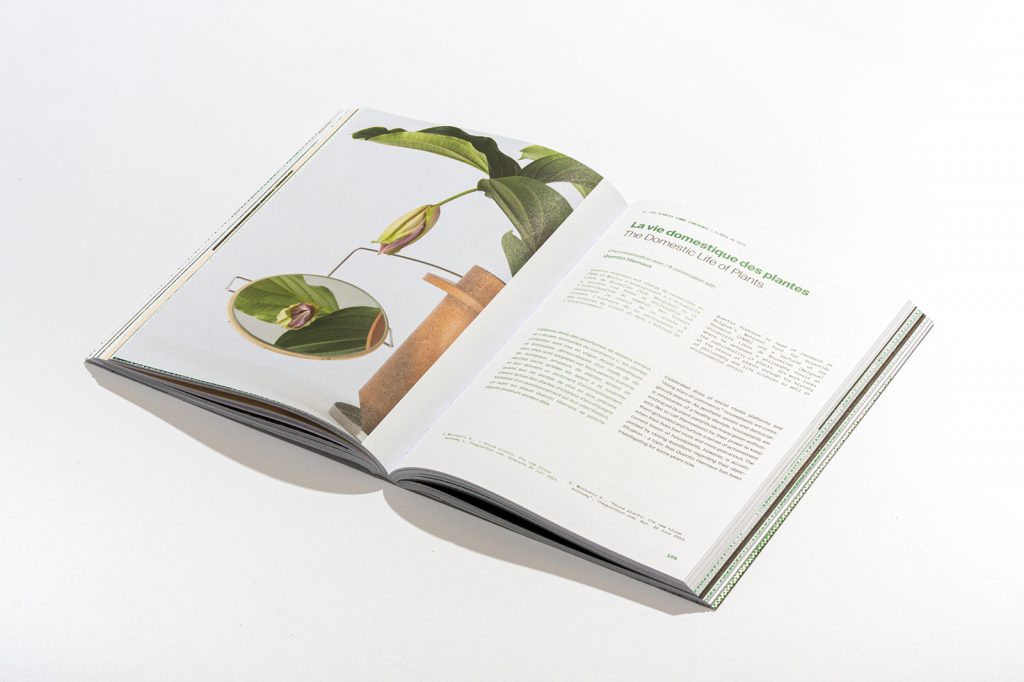

One of the people we interviewed for the exhibition, Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia, who wrote The Life of Plants, described design objects, especially the ones that are inside the home, as prostheses of our bodies to understand the world. And I think it’s a very powerful idea that these objects that we feature in the second chapter are creating a bridge between us and the plant world. It is true that we’re keeping these beings captive, and there’s a paradox there with plants as pets. Is a pet a free animal, or not? But at the same time, the other philosopher we interviewed, Quentin Hiernaux, also said that when you have a plant in a home it brings life into that home, in the sense that a potted plant needs you to stay alive. So it creates a bidirectional relationship where I need you to feel better, and you need me to water you.

And then the third chapter is “Plants as Allies,” and there, we have more speculative designs that look at future alliances or future cooperations with plants. We have robots that are driven by plants and robots that translate plants’ needs, as well. What shaped this chapter, in particular, was the amount of literature that has been produced in the last decade highlighting the fact that plants have a capacity [to be more than simple materials or decorative objects] that we’ve refused to see until now.

Most of the designers and artists that are featured in this chapter are not just artists or just designers, but embrace a transdisciplinary approach.

MOLD:

There seems to be a greater interest now in plants because people have been spending so much time at home. Do you think that we are moving more in the direction that Plant Fever showcases? How do you envision the near future for plants?

D-O-T-S:

The number of projects dealing with plants is growing, and it’s certainly something we see as a positive direction into a new way of looking at plants. But there are different projects that we showcase in the exhibition that show potential problems as well. For instance, some projects that we present are very technologically oriented, and that could create an even bigger distance between us and plants. A project by Helene Steiner, a design engineer, is implemented in agricultural fields and greenhouses so that the people who are cultivating plants can understand the plants’ needs without being out in the field directly. They can see their plants’ needs—water or whatever—from their computers. It is a way to create a bigger bridge between the plants and us, but is perhaps creating a new distance between us.

A lot of people were buying soil and plants to cultivate tomatoes, for instance, on their balconies as a way to escape lockdown. It revealed that we need a new connection with nature and plants. Whether they’re potted or in a small garden, plants create a connection with nature that is outside of the city. Houseplants are these intermediaries between us and what’s out there.

Drouet and Lacrouts’ book, Plant Fever, includes essays, interviews and visual explorations centered around phyto design, and is available for purchase online. After the first presentation at the Belgian museum CID au Grand-Hornu (18.10.2020 – 07.03.2021), their touring exhibition will be on view at Museum für Gestaltung Zürich from December 3rd, 2021 until April 3rd, 2022.