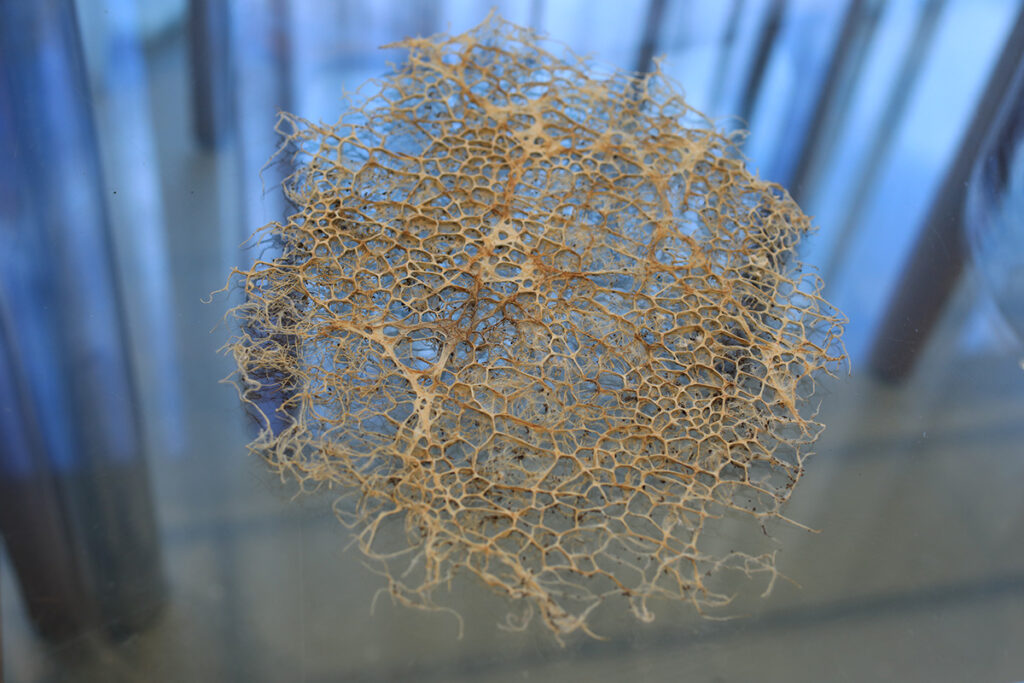

Diana Scherer harnesses the innate yearnings of plant roots to reach towards nutrients and water as the foundation of her process. Published last year, Interwoven is the culmination of an ongoing project led by the Netherlands-based artist. She started with an experiment: extracting plants from pots and observing the root bound forms. Over time, these structures evolved. After publishing her inaugural book, Nurture Studies, she began collaborating with scientists and ventured further into her pursuit of weaving roots into textiles. Trialing various plant species, she treats roots akin to skeins of yarn, exploring textures, thicknesses, and tones. Scherer devised a method to guide them through templates— some of the resulting motifs meticulously planned, others shaped by the unpredictable spontaneity of the roots’ will.

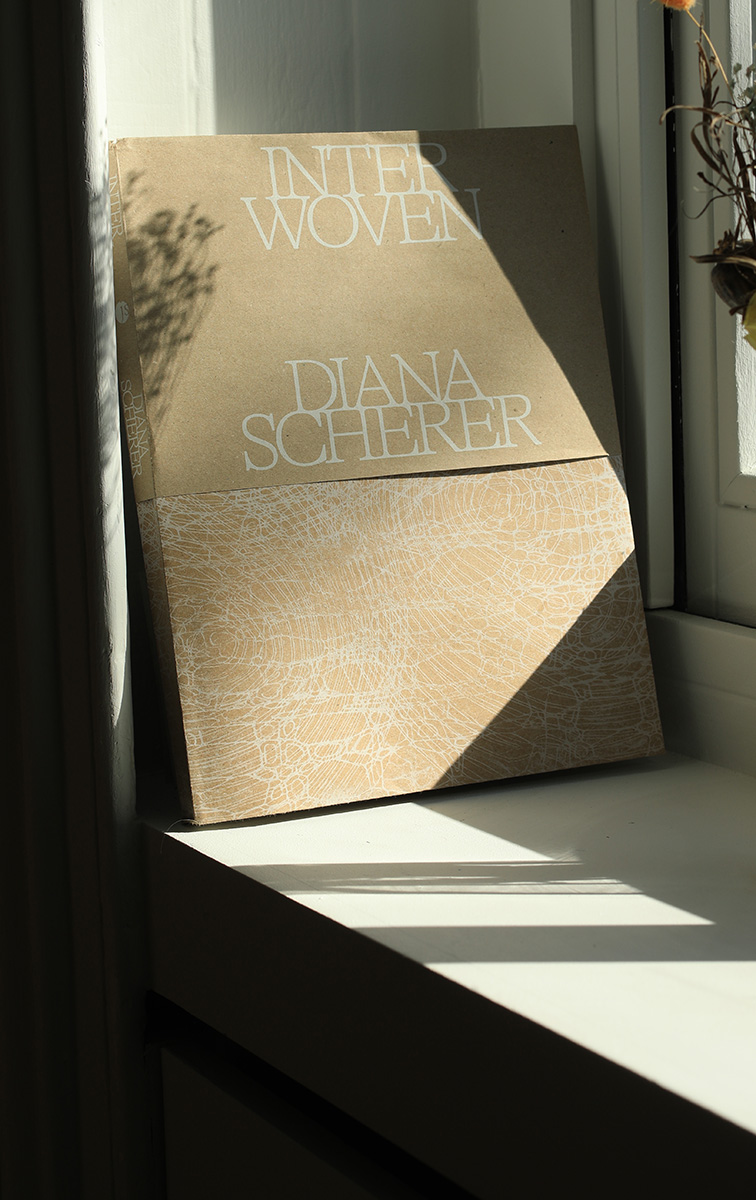

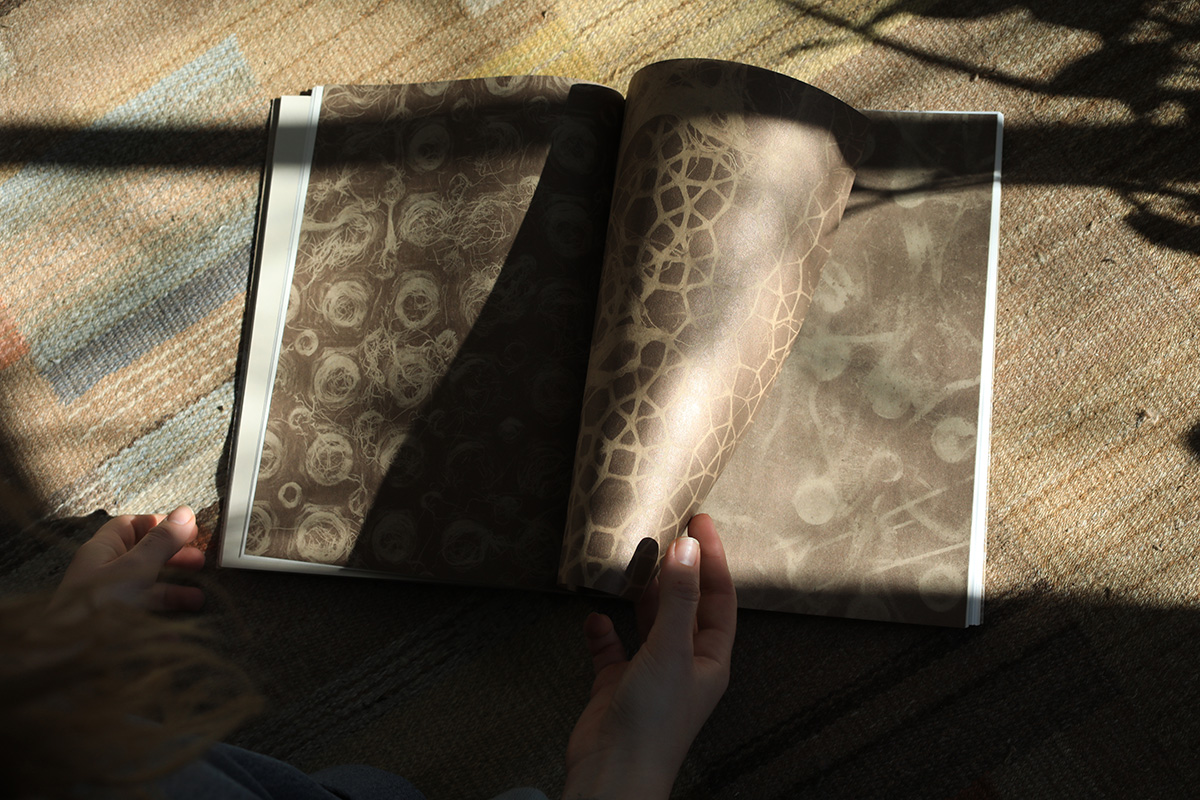

In our interview, Scherer discussed the tactility of the book itself and envisioning it as its own entity. Designed by Mainstudio in Amsterdam, the book binds varied dense and translucent paper, hugged by a dust jacket printed with magnified woven root arrangements. The work is contextualized and thoughtfully prodded in a series of essays, written by authors from various backgrounds in art, design and science.

“It was always quite clear—I didn’t want to make a catalog,” Scherer shares in an interview with MOLD. “I wanted to make a work in itself. It was a long discussion with the designer and the publisher, how to manage [making] a book where I wanted the whole project in it, with all its facets, and a lot of text. And how to make a beautiful book, which is also kind of conceptual. When we were choosing the paper—and we started with the paper really–which had to be natural, [it is] wood containing paper which also decays very soon if you put it in the light or in the sun, it will just change the colors of the book, which normal paper doesn’t. [The designer wanted] it to look like a tree, if you see it from the side, it looks like all these little lines. And for me it was important to put it together everything in one big project and to tell my story.”

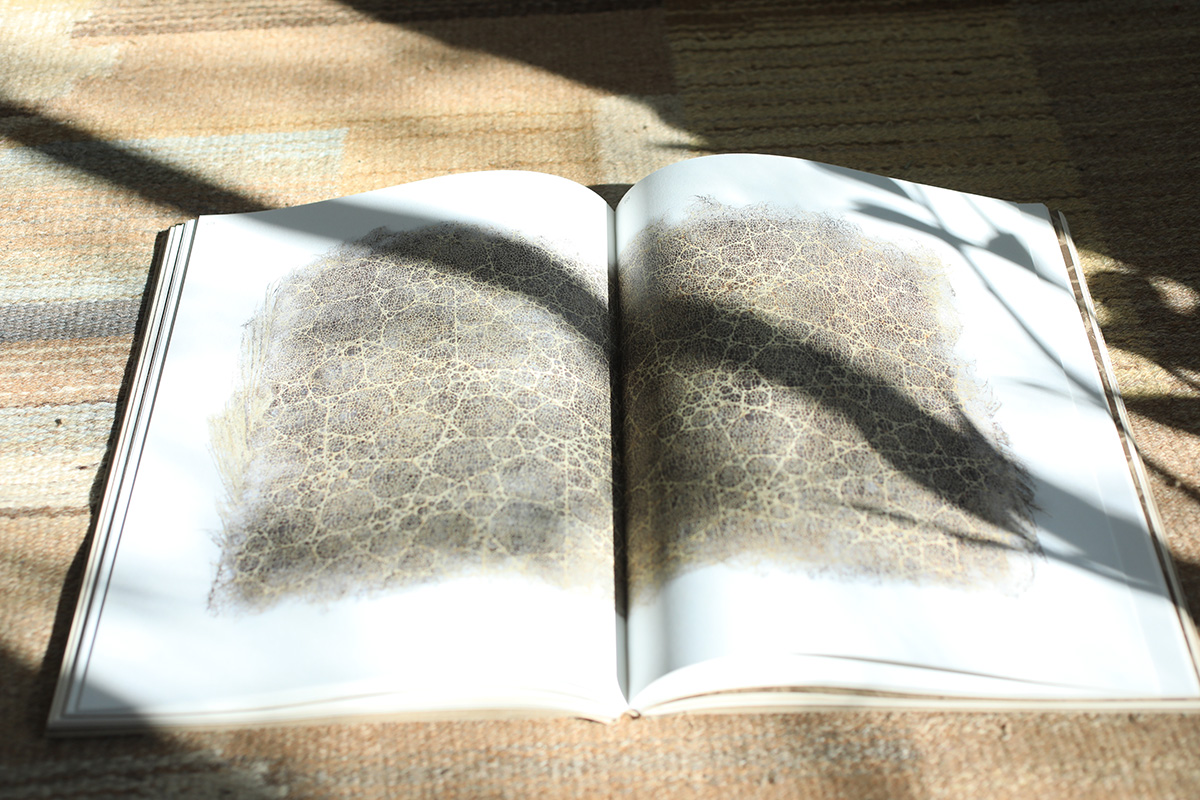

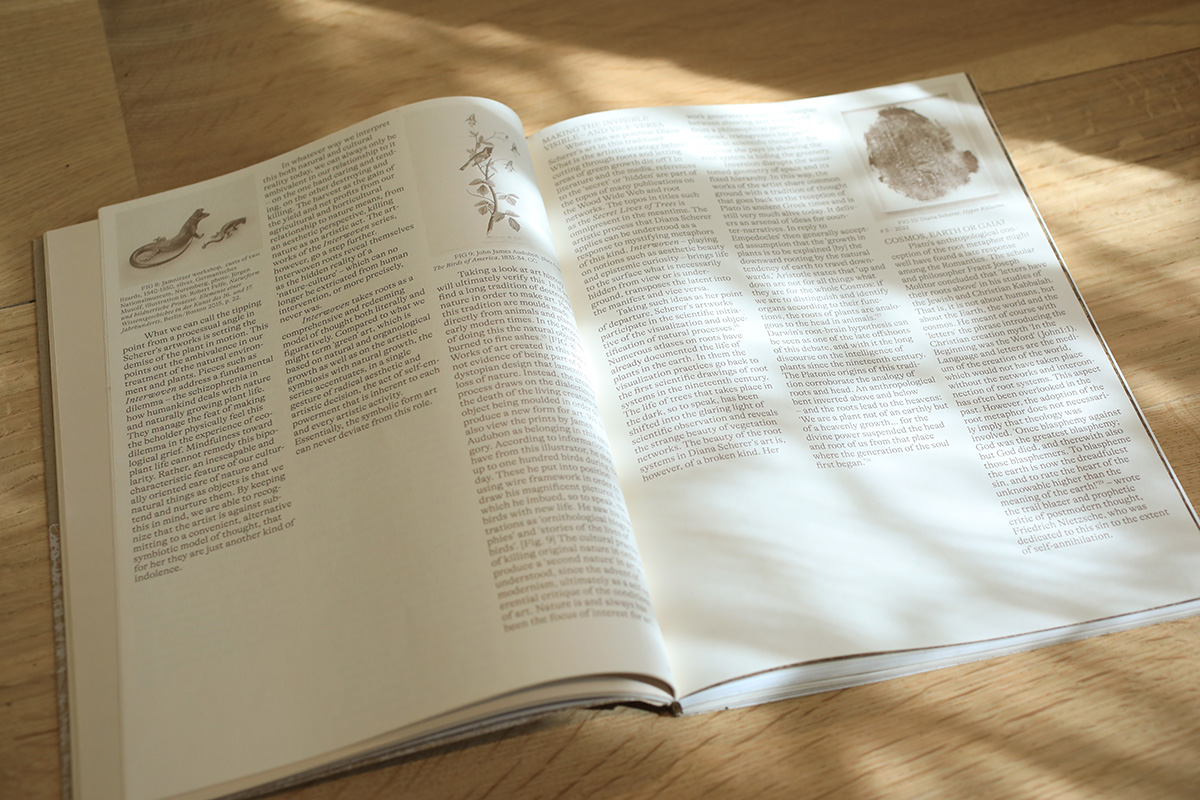

Scherer’s work dances on the boundary between organic and manufactured. These systems of growth, thriving in both community and subterranean conflict, suddenly emerge to the surface– the warp and weft reveal the delicate movements made. In the book, authors Judith Elisabeth Weiss and Herbert Kopp Oberstebrink describe: “Artistic processes and horticultural practices merge in the time-consuming genesis of the material of the artwork; a line cannot be drawn between them in this phase” (42). The weave patterns represent an amalgamation of various structures: “Although a computer program is behind the operational procedures used to make the form templates for root growth, the material making up the data that was fed into the computer beforehand was generated under natural conditions (honeycomb, spider nets, cell structures) as well as culturally (grids, tire tracks and bubble plastic). In other words, when Diana Scherer creates her worlds, the beginning is marked by hybridity with culturally and naturally shaped materials and artistic design” (42).

Though Scherer’s work may not epitomize a perfect, uncomplicated model of symbiosis, for her, laying bare these questions is an important feat in reconstructing human-vegetal collaborations. In the Western paradigm exists a presumption of human superiority over plants, which actually suggests a deep-seated fear, author and curator Giovanni Aloi argues in the book. “Humans are terrified at the idea that plants might be intelligent because so much of the ethical and cultural structure the West is founded upon an implicit reliance on the subjugation and lack of care for plant life. This enables us to exploit and destroy plants and the environment as needed” (60) Interwoven calls on us to examine the complexity of multispecies relationships and underscores our true interconnectedness, because this hierarchical organization is costly and dangerous. “We are today more and more aware that the cultural distance we’ve created between us and plants is among the leading causes of climate change and environmental degradation. Reconsidering our relationship with plants might be the most important step we take forward reversing our detrimental impact on the planet” (57).

The book highlights the prominence of root imagery in Indigenous art and how roots, world over, have been utilized in medicine and botanical illustrations as tools for identification. It contends that in times when mythology and botany were more intertwined, roots were imbued with fantastical stories and attributes. Although, over time, Western culture has turned to overlook and even disparage roots, in particular. Western botany, Aloi explains, is shaped by Christian ethno-religious influences and centuries of demythologization of our collective consciousness—these metaphors prioritize the beauty of blooms, flowers, and leaves, while viewing what lies beneath the surface as undesirable, “culturally linked to the darkness of hell and the coldness of death” (59) As depicted over time through imagery- “the emphasis shifted from growing to harvesting; from natural cycles to possessing nature as a beautiful object” (59). Interwoven challenges this extractive mindset by shedding light on material histories and emphasizing the inherent power of roots as an end in themselves. Just the delicate, sensorial descriptions of roots alone are evocative and paradigm-shifting. “Wheatgrass and oats are soft and white […] morphing their small stems into lace-like strands in a matter of weeks. Verbena is chosen as an alternative to flax, it’s silkiness echoing the composition of linen, whereas other plants such as chamomile and daisies have much hairier root filaments, making them a cuddly substitute for wool” (148). Ignoring roots, as has been our cultural practice for centuries, has led to overlooking valuable potentials.

“We are not used to [it] actually, the roots were overlooked things” says Scherer. “We eat them, but if you see in farming and agriculture, when they harvest it, very often throw away all the root material. And so I discovered this. It would be a wonderful way to use this rest material or to look at it in another way also concentrate on the overlooked things in the cultural world. And there are so many.”

When asked about her practice contributing to a non-hierarchical and cooperative relationship between humans and plants, she responded: “It could.. [but] I also use nature, you are very aware, of course. Because my works, they’re dying. It is more about raising all these questions. This is always what I emphasize: Could it happen that we work together? There is a fusion and there’s something beautiful about it. But it’s also the other way around- that I kill my work. And it’s important for me as an artist, also to show it. They are symbolic images, and they stay, and people think about it. That’s my job, I guess. And then the rest you can keep to the scientists or climate experts. But this is for me as an artist. And I still hope, of course, that everybody sees beauty in it.”

Artists and designers wield power to uproot cultural systems and foster growth in subtle and unconventional ways. In their essay, Kopp-Oberstebrink and Weiss suggest that art has a power to do so by rendering visible while they might otherwise be “on the peripheries of our field of perception” (44). It can establish precedents for new models and provoke alternative possibilities. “It is apparent again that we need art and its powers of distillation to absorb ‘plants in the architecture of our imagination’ and in this way to come to an appropriate understanding of ourselves as part of nature” (45)

The contributing authors in Interwoven collectively challenge the notion that humans are detached from nature, emphasizing instead that we are integral parts of our environments. They deconstruct the distinction between “inside” and “outside” realms, and propose embodied processes, rituals, and architectures that facilitate this interception and propose alternative relations. For example, “gardens and enclosures, are delimited spaces in which both humans and plants domesticate each other, exchanging and nurturing reciprocals and expectations, becoming a meshed in interwoven dependency” (63). Following this line of thought, one can follow a practice rooted in empathy that starts with visualizing beneath us as we navigate our surroundings. With each step on soil or pavement, we can establish connectivity and acknowledge interdependence with various root networks– botanical, electrical wires, pipes—contributing to the upward stream of energy. Scherer shared how she engages her research practice in her everyday life:

“I walk–I look at everything very differently. In the way of: what can I use? How can it grow? And also what has changed a lot is looking at the daylight, because I work with growing light. That means every little shift in the light, or temperature, almost like [I am] a plant, like “it’s a half an hour longer today!”

Further integrating ecology with art and design presents an opportunity for better practices of care, and Interwoven propels this undertaking. Scherer shares her experimental approaches to sustainable art-making, such as tasting roots while she works and repurposing discarded materials. On a larger scale, there are a myriad possible collaborations between art and design with food economies. An idea from Scherer’s thesis, as presented by Author Phillip Fimano, even suggests a future of cultivating biomaterial alongside hyper-abundant vegetation like wheat to minimize waste (149).

Interwoven encourages us to engage materials that we already cohabitate with, and presents the possibilities of interdisciplinary uses. Wandering through the visuals of root textiles and engaging with the author’s inquiries sparks a curiosity, tenderness, and an insight into the stakes in how we relate to the nonhuman world. Maybe small yet significant nonetheless—preservation, propagation and nurturing plants holistically serves as a meaningful starting point.

Release date October 2023

Publisher Jap Sam Books

ISBN 978-94-93329-03-4

Price €39,95

Editing, compilation & concept Eleonoor Jap Sam, Mainstudio (Edwin van Gelder), Diana Scherer

Texts Giovanni Aloi, Phillip Fimmano, Colin Huizing, Herbert Kopp-Oberstebrink, Norbert Peeters, Judith Elisabeth Weiss, Jiwei Zhou

Translation Christina Oberstebrink, Caspar Wijers

Design Mainstudio (Edwin van Gelder)

Number of pages 208

Book size 23 x 32 cm

Binding softcover, American dust jacketLanguage English