The thought of sweet, spicy chutney while fasting during Ramadan makes the dry mouth salivate and a tired mind rush with scrumptious thoughts of fried golden delights. It soothes and refreshes the heart while exciting the mind. Chutney is a regional delicacy which can be made in countless ways and paired with countless foods for an elevated flavor experience. South Asian families across the diaspora dip, slurp, layer, dab, mix and more with this versatile condiment, carrying pieces of their tradition, preferences, joy and community throughout the world.

Words by Hiba Zubairi. Images by Osman Bari.

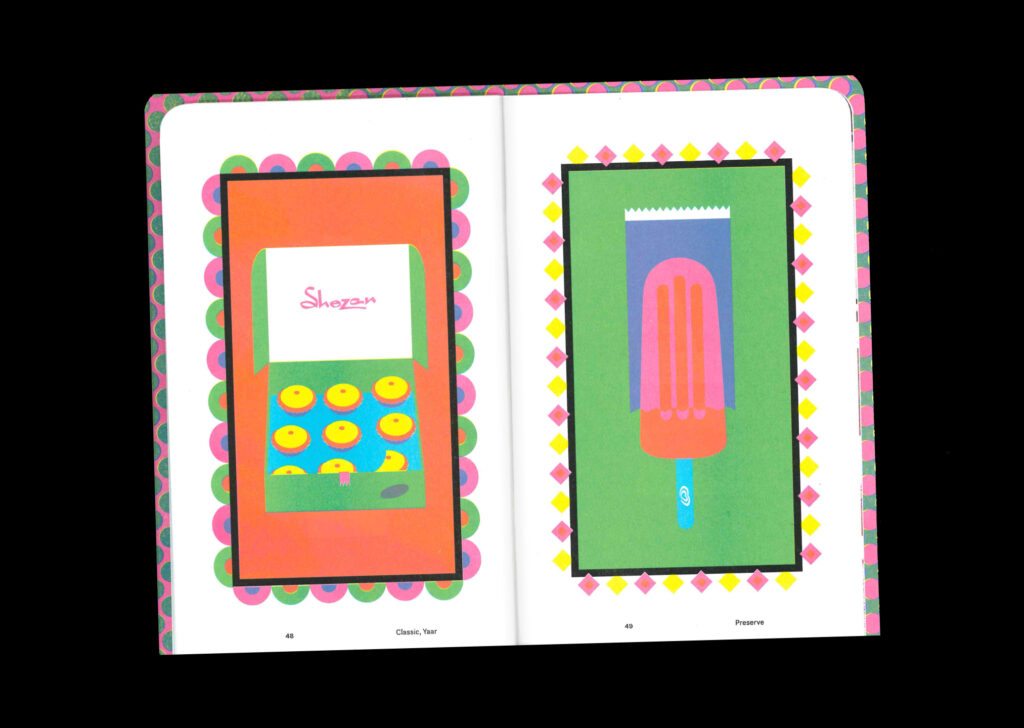

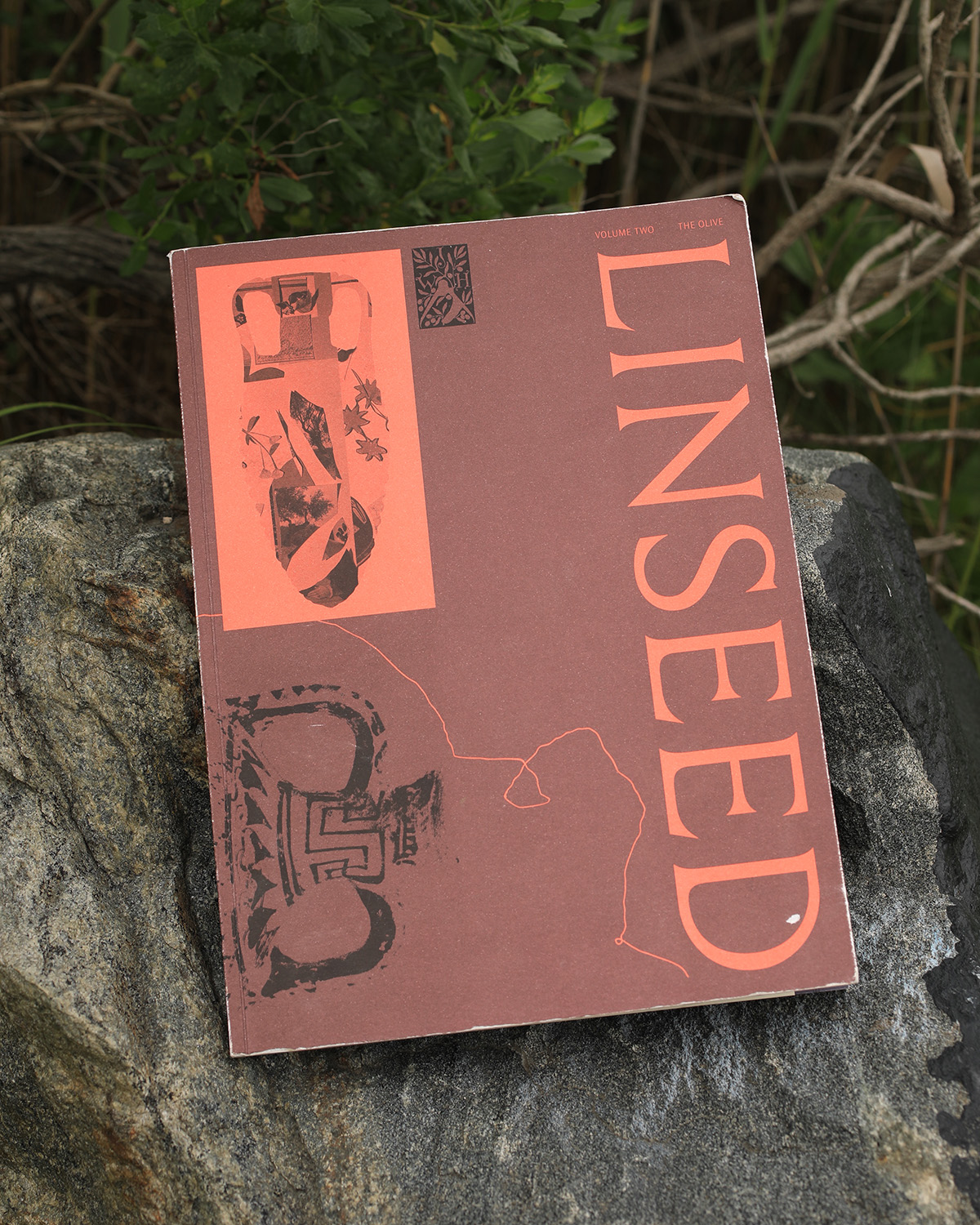

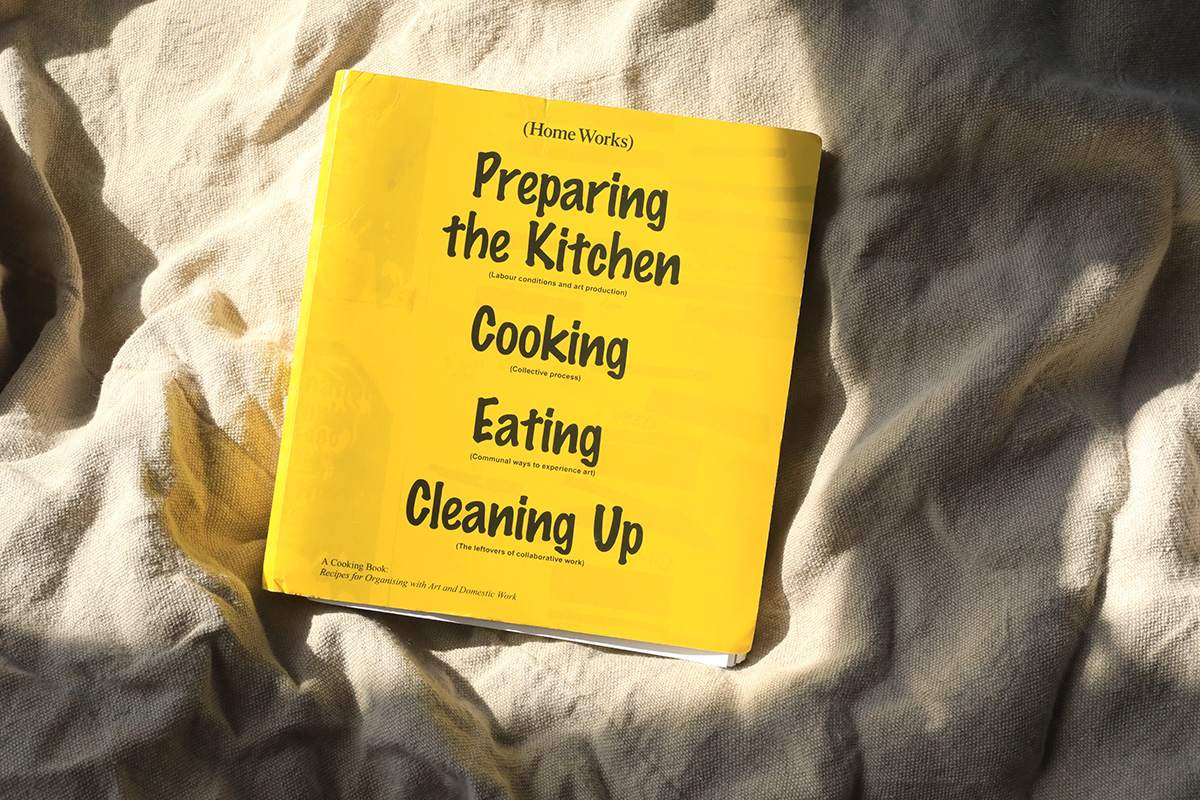

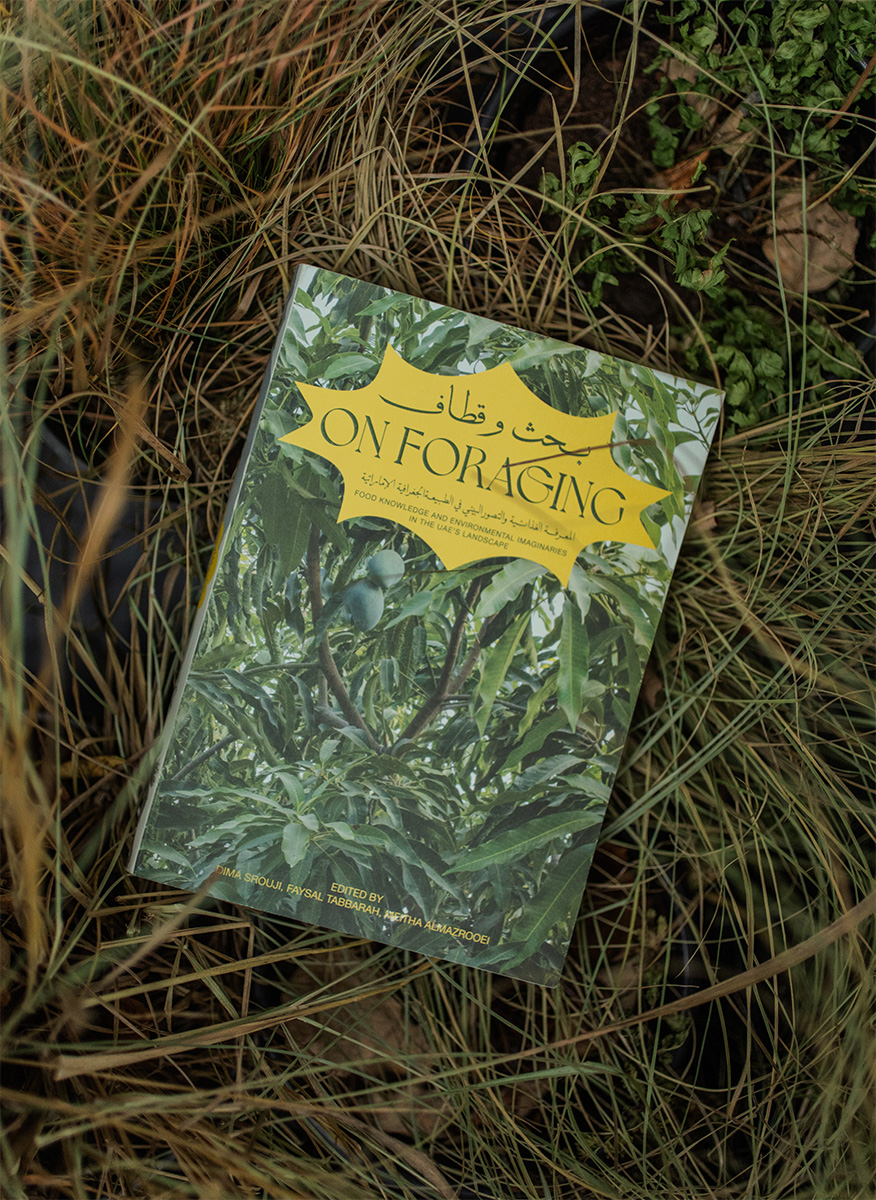

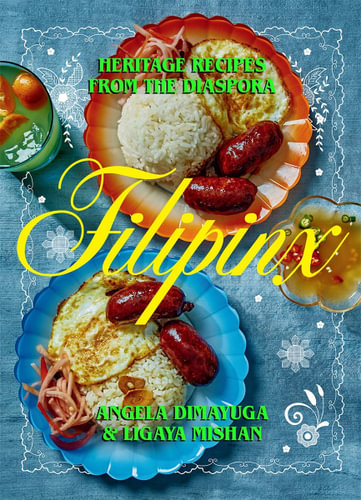

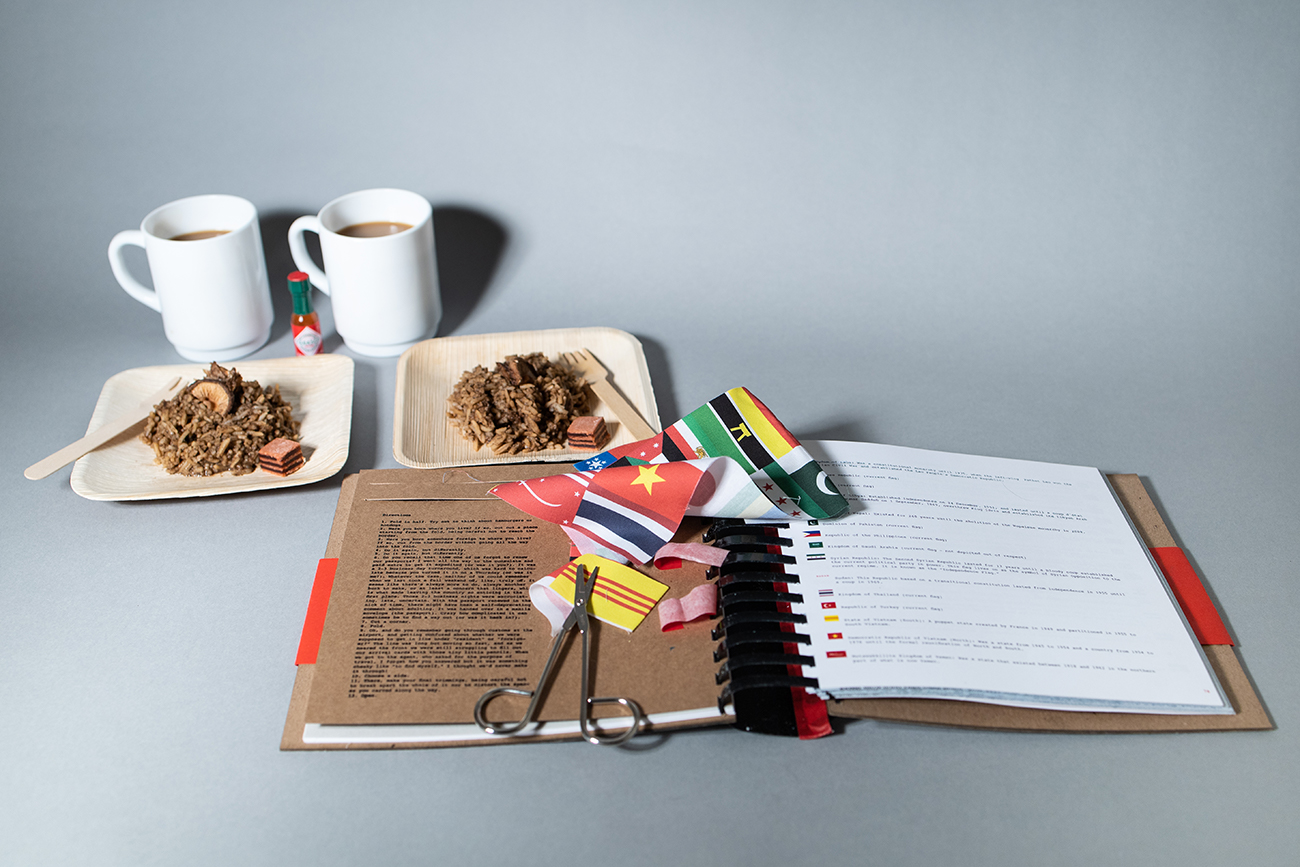

These feelings of comfort, excitement and family away from home form the thematic basis for the indie publication, Chutney, an annual publication curated, designed and edited by Osman Bari, a graphic design masters student at UAL in London. Having recently published their third volume, Chutney delves into the stories which exist within cross-cultural pollination. A collection of essays, personal narratives, illustrations and recipes, the small but mighty publication holds fragments of lived experiences which capture the indescribable essence of home away from home. Guided by the fundamental recipe for chutney, food presents itself as a guiding light through each issue – for where does comfort and wonder meet more intimately than over a meal?

MOLD sat down with Osman last year to discuss Chutney’s inception, community and future, in a conversation about how food captures identity in a way that transcends labels and preconceived notions of worldly understandings.

HIBA ZUBAIRI:

You named your publication Chutney and it’s structured based on the rudimentary recipe for ‘chutney’ – why is chutney compelling for you?

OSMAN BARI:

The name is inspired by this classic idiom that my mother (and a lot of other mothers) says to me which translates to “don’t make chutney out of my brain.” The fact that chutney could warrant an idiom of its own and go beyond a cultural food and represent more within our language, within our community and how we interact with each other was something that was really important and I was really inspired by. So that’s why the publication was named Chutney but also as it happened, these three rudimentary steps emerged as an interesting way to frame the content. So rather than having themes, all the stories are centered around a three-part recipe – chop, mix and preserve. They’re all pretty similar, somewhat interchangeable, but the fact is, they have their distinct identities within the publication.

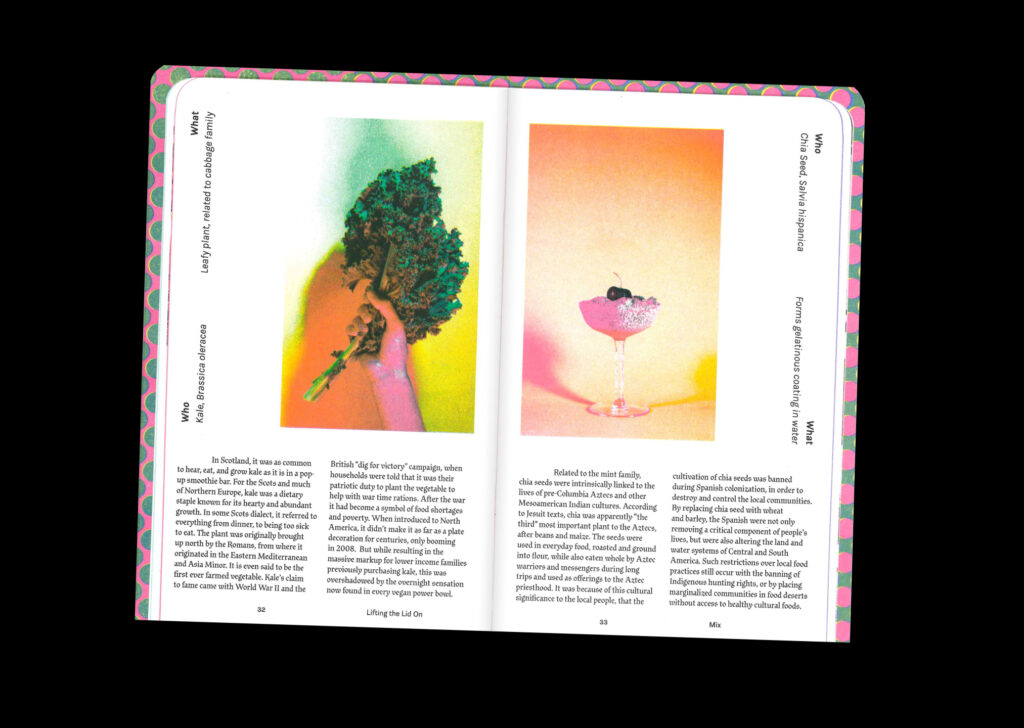

Chop is about sharing fragments of ourselves, Mix is about intersectionality and cross-cultural influences, and Preserve is about histories and legacies within communities. These three parts are presented to contributors, and it’s up to them to decide what they resonate with the most and where they see their story fit in. I try not to be too prescriptive about it.

HIBA ZUBAIRI:

There are so many stories about culinary landscapes and experiences explored through narrative, recipes and illustrations. Where does the medium of food come into Chutneys curation and what type of experiences does it help shed light on?

OSMAN BARI:

It was always going to function in the publication due to the nature of the name. It wasn’t an initial thing that I wanted to focus on but food is this amazing thing that brings people together and everyone’s got a story about a certain food. It’s a vessel for so many different things—memory, nostalgia or migration of cultures and identities.

People really latch on to that. Since the directive of each step is somewhat vague or loose, food is a really comfortable and recognizable way to frame one’s experiences, even to just understand yourself better and where you come from, and the cultural dynamics in play with where you are.

H.Z.:

Building on that, food is a sensory experience but often functions as an identity marker. What are some examples of ways your contributors have used food to talk about experiences larger than itself?

O.B.:

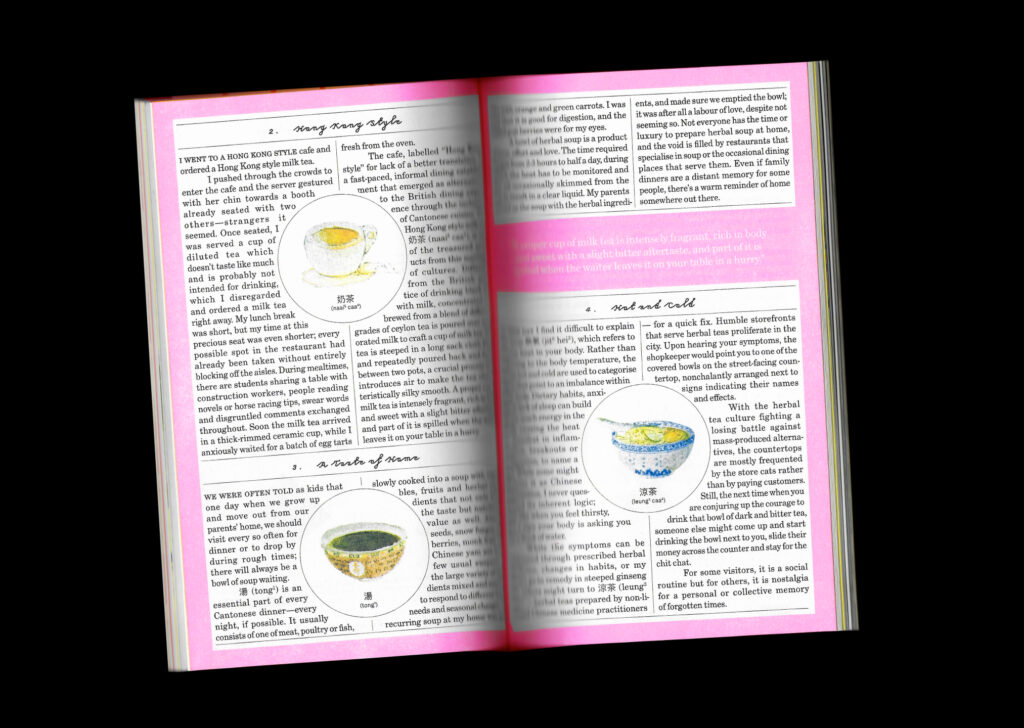

I think one of the key stories that comes to mind is Jonas Chin’s story in the last issue. He essentially wrote five vignettes on Chinese dining experiences, each was framed around a certain food. The first is different types of Chinese dumplings, which he also illustrated beautifully in watercolor alongside the written vignettes.

He talks about the Hong Kong-style cafes where he orders milk tea and the people he comes across in that environment. He describes the environment as informal, super busy, with multiple activities happening at once. There are all these different demographics coming together in this space that is serviced by food. The purpose of the space is to bring people together for food.

That’s one of the stories. Since there was this underlying sense of nostalgia, also a sense of loss to it, I found that was really powerful. Jonas talks about how he’s caught between the cultures in Hong Kong and Canada. You can’t replicate those experiences. It’s not about authenticity, it’s about certain foods being linked to certain settings and experiences and while you can transport that flavour, there is this sense of loss when it is experienced outside of that setting it originated from.

Even when I say originated, it’s untrue, because Hong Kong style tea is obviously derived from a colonial context, so there is no kind of ground zero for food in those experiences. Just the nature of food and migration and travelling brings together this wide landscape of experiences and all those memories can come flooding back in a bite or a sip. I thought it was a really great story.

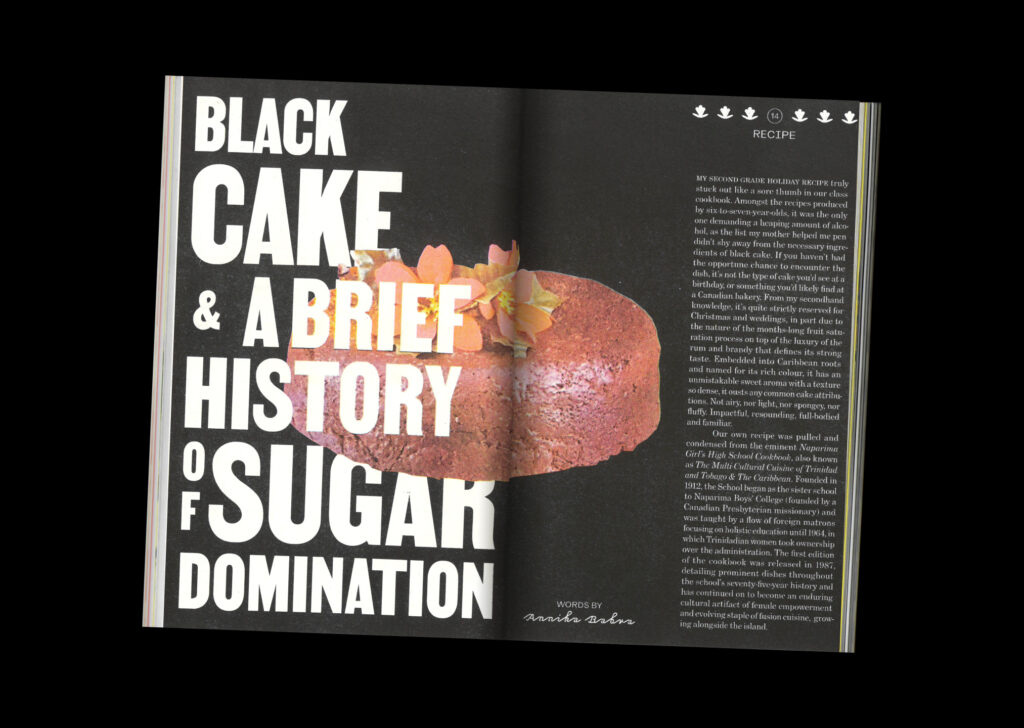

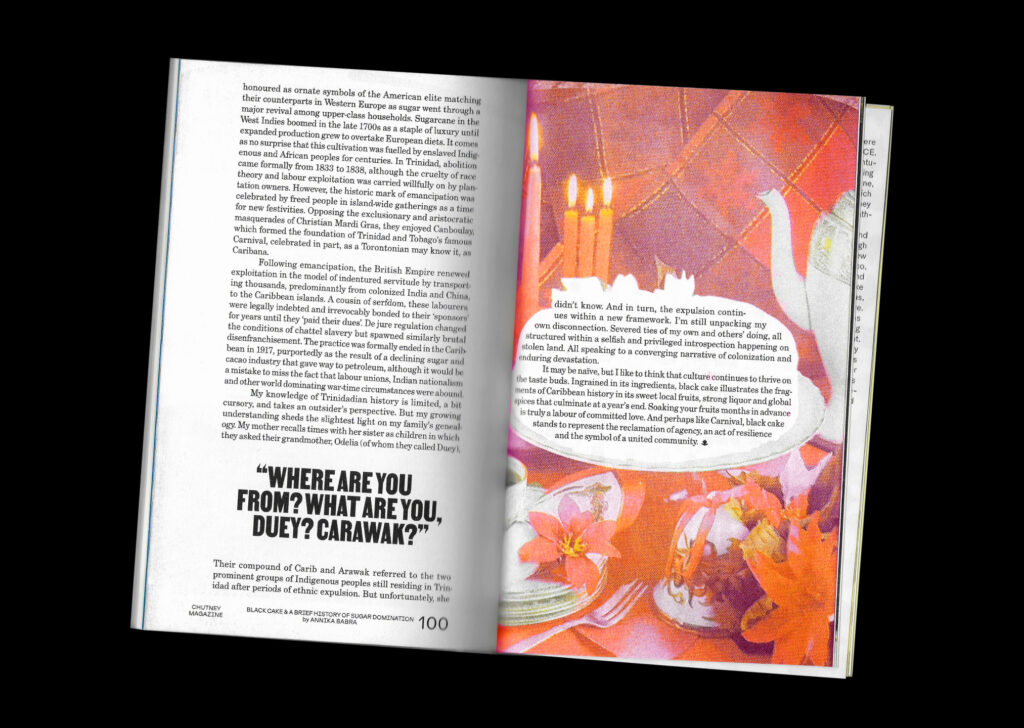

Also, Annika Babra’s piece on Black Cake and indentured servitude on sugar plantations in the Caribbean was memorable, because as we know, it always comes back to colonization. She begins the piece by describing how Black cake was a recipe she used to bring to class in middle school to share with her peers, but it was the only recipe that had alcohol in it.

She then delves into the history of the cake and its importance as a celebratory food but frames the history of slavery on the islands’ sugar plantations.

There’s just so much that food talks about and the nature of where it comes from. There is so much to unpack there.

H.Z.:

Food landscapes are becoming so diverse and intersectional. We’ll travel to different cities in North America and eat the “best” bowl of ramen or try finding the best tacos. So many people had to move and migrate and find community for us to be able to have this food experience is wild to consider. I know you grew up Pakistani just like me, and I think we can agree Pakistani food does not get its due in the mainstream, but has such a meticulous process to it in terms of building flavours. I feel like there are certain cuisines that get passed off as being lesser than because of certain stereotypes.

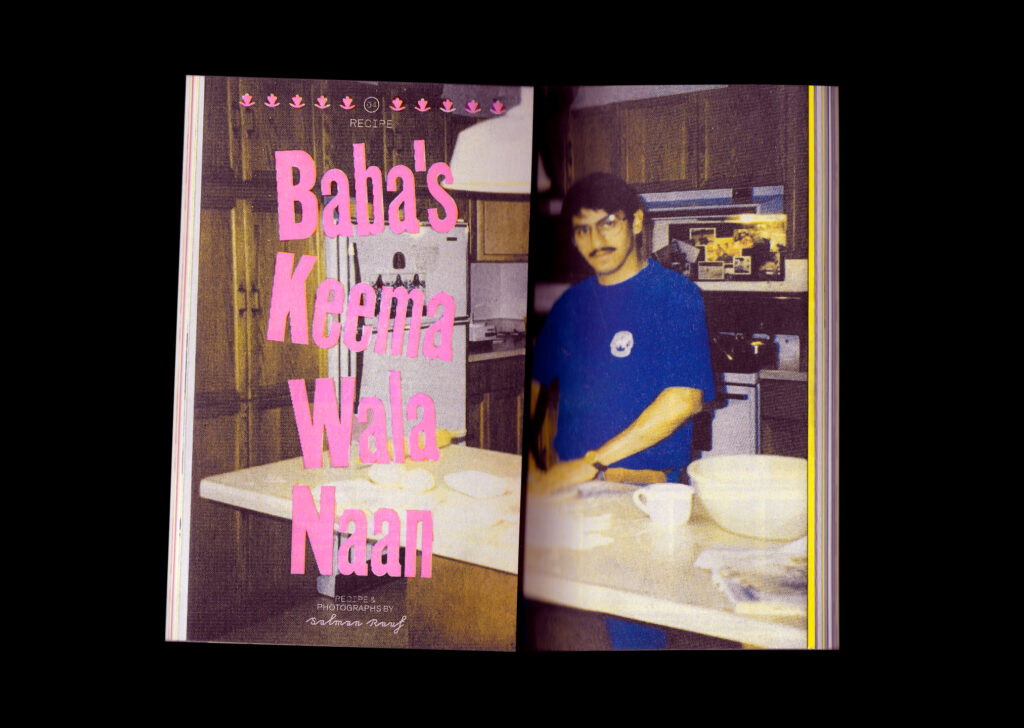

Even being Pakistani, I grew up being nervous about taking Pakistani food to school because my peers would find it too smelly. There are a few moments in Chutney that point to those foods, which can be moments of contention in public, but are moments of connection at home. Such as Salman’s recipe for keema naan which was something he connected with his dad on.

It seems food plays a different role in different settings yet the materiality is continuous. From curating Chutney, what are your thoughts on how these transcendent experiences are part of diasporic or cross-cultural living?

O.B.:

One of the important things would be the individuality of the experience. Obviously, food is a communal medium that brings people together and forms shared memories through eating, talking, telling stories and what not. But I think the thing with Chutney is we strive to allow individuals to speak to individual experiences and not have to take the role of a spokesperson for their identity or demographic.

That’s something I appreciate about the contributors. We related to Salman because we’re also from a Pakistani background and we love naan. (laughs) But you know, I’ve never made naan, let alone made it with my dad, so reading his experience helps me see it in a different light and realize how important it is to him. Somehow, it’s this interesting duality of community yet individuality and that’s why food can, I don’t want to say, help you find yourself, but we’ve all got our own taste and preference and relationship to it. And that’s so rich. It’s just impossible to stereotype any community then, because you can’t paint anyone with the same brush. Within our communities there is so much variety and so much depth of experience.

H.Z.:

It’s interesting when you talk to people within the community from different households because we’ll eat the same things, like daal and biryani, but everyone has their own variation on it. The tweak in spice or ingredients our moms make. Being able to share the same comfort and warmth with those meals but having a slightly different flavour experience that has to do with personal tradition collected over generations. The idea of food being a material collection of memories over generations is such an exciting and warm thought to have. And I think so much of the work being done with Chutney that highlights the individual experience really helps formulate the nuances of life. Where the magic lies.

How do you think reading people’s stories in print offers a different relationship to the reader versus viewing them on social media, or reading them digitally?

O.B.:

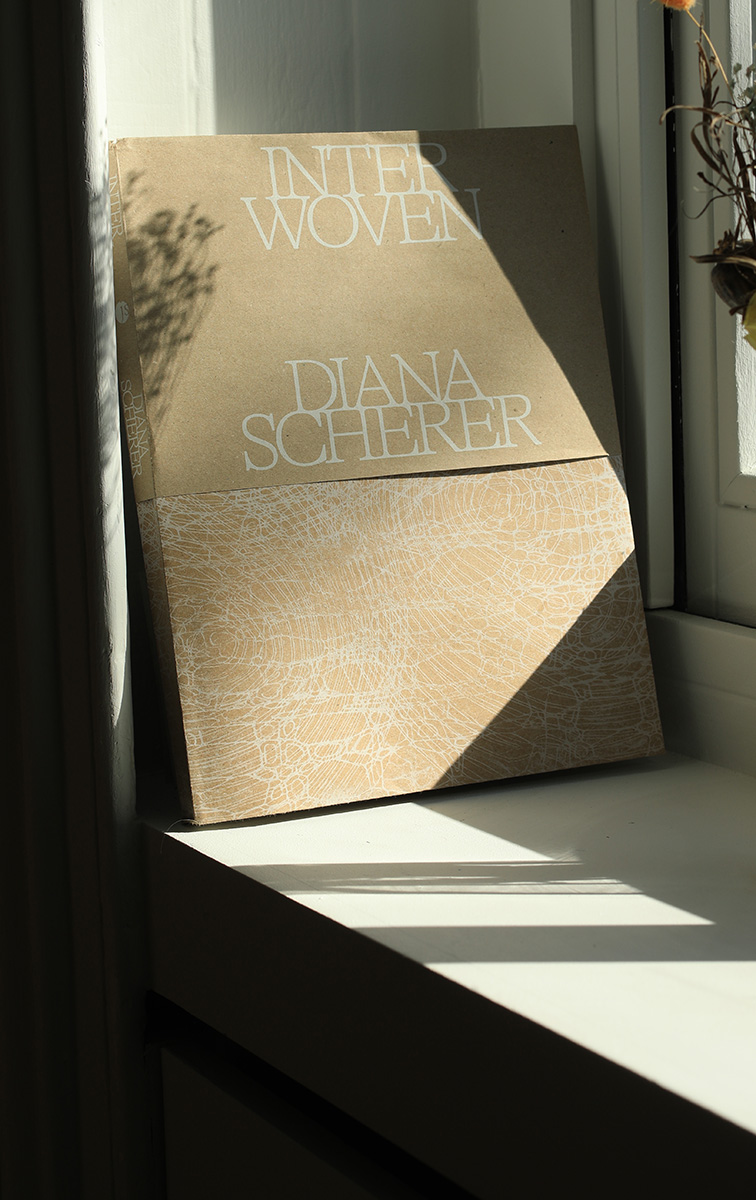

To me its really about the personal connection to it. It’s nice to be able to hold something in your hands. There is a tangibility to it. A slowness, even though I hate to use that verbiage. You can take your time with it, revisit it. Different mediums have a lot to offer. For example, videos, when it comes to food, they highlight a visceral experience, you can imagine how it might taste or smell. I think with print the possibilities are slightly more limited. Which is why its more of an interesting challenge to convey experiences like eating food.

With print, it’ll come in the form of illustrations, pictures, recipes, stories. So, if you’re able to convey that in a successful way it’s even more effective. Photography is also really important when it comes to food and print. I dabbled a little with food photography in the first issue. There are certain connotations to how you present the food and recipe in print versus digital media.

H.Z.:

Those limitations steer you in a certain direction. Things like food photography and videography are all tools to make food appealing without people being able to taste, smell or touch it. I probably consume more food online than I do in reality. Chutney doesn’t offer that direct connection to consumption, it really builds your image of a food through someone else’s.

Do you think the sensory experience takes a back seat in these cases or is it utilized as a tool by the contributor?

O.B.:

I do think the sensory experience takes a bit of a back seat in this case, it’s not so much of a curated attempt to make you want a certain food, its more about the larger story at play. For example, with Salman’s piece, his dad who is speaking, doesn’t even describe the naan or its delicious qualities, he’s just explaining to Salman where they come from and the setting he associated with it. His explanation of that is very visceral but its not about the final product. Perhaps that’s the key difference between how it would be presented digitally versus in print. Its not about the final outcome, its about the story of the process.

Even with Jonas, his illustrations are really beautiful, but they’re stylized watercolours. Not super accurate, high definition images. With Annika’s piece as well. There is a scan of a childhood cookbook for hers, and the graphics are collages. I think it’s up to the author at the end of the day. I think the sensory experience is there but through this lens of nostalgia framed by the overall story, rather than just the food like, “This is a really juicy steak.” There are publications that do that its just not what Chutney is about.

H.Z.:

Food is more of the medium, than the message.

It goes beyond food. There is a focus on physical material being a guiding light in recalling your own experiences. There’s a weight to that. When people have contested identities that aren’t always understood in the mainstream, there is a lot of back and forth in terms of right and wrong, true and false. Material has this ability to surpass that. Through its composition, age, alterations, iterations – it tells its own story. It’s up to us to interpret it through our own lens and context. What Chutney does is it takes that focal point of the material experience and uses it as a bounce board to talk about individual experiences.

It shifts the narrative from having a contributor explain themselves for validity to having them express themselves for the joy of connection and shared experience.

I’m not sure if that was your intention, but what does that mean for you? How do you enjoy engaging with that space?

O.B.:

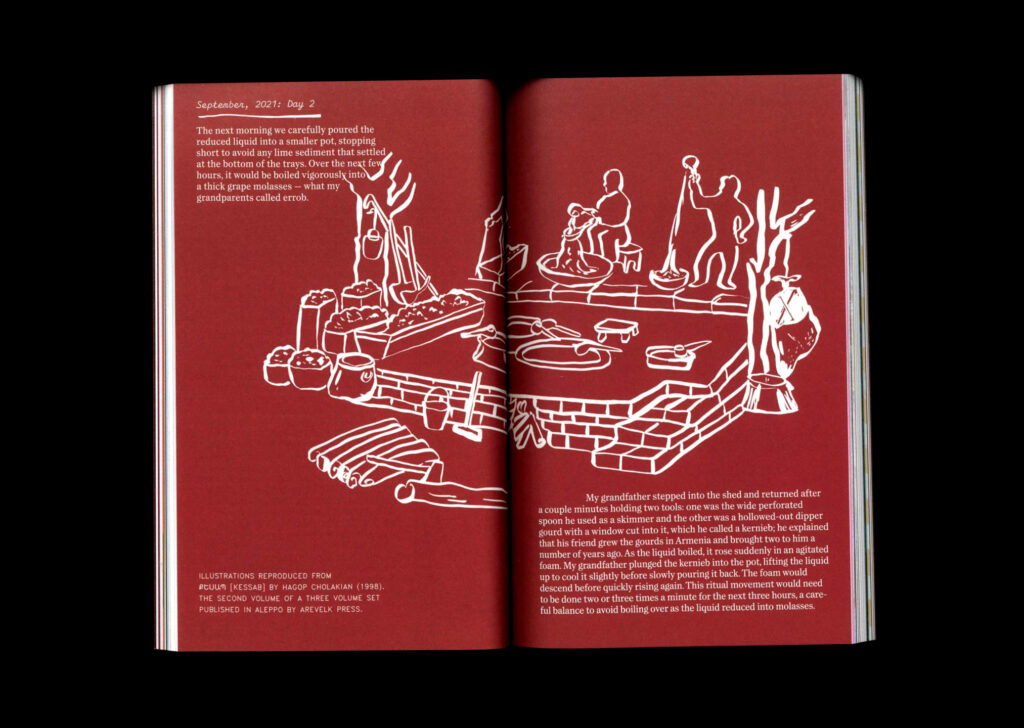

My role is interesting, because I’m inviting all these people to open up and be vulnerable but as the designer, I have more control. I don’t necessarily work with them, I use my own style. But that seems to resonate with people. My own memories shape the publication, from the sweets my grandparents used to give me to signage in Pakistan. When it comes to design, I’m trying to draw upon that without being too culturally specific. I want the publication to feel celebratory. I want to represent people’s stories in a manner that feels uplifting. It isn’t clean or austere. It gets messy in some bits and that’s reflective of the name. Chutney comes in so many flavours after all.

That’s really the material experience I wanted to capture. With issue two, we had the thermography cover which builds on this sense of touch. All of this is really important. It’s connecting on an emotional and psychological level. It adds a bit more when you can run your fingers over the cover and you feel something. Or you use risograph printing, where the colour rubs on your finger tips. It enhances the reading experience. More so, it enhances the characteristics of the publication as an object, a vessel for people’s stories.

H.Z.:

At what point do you feel you become a part of making the story? Or do you feel there’s pressure or struggle with trying to design the best way to convey someone’s story?

O.B.:

I’m trying to be conscious of not feeling entitled to people’s stories and their voices. That’s not been the intention at all. It’s more of an invitation to be a part of the process than an expectation. Even in the editing process, I find myself wondering if I’m taking away from this person’s story by editing down. Luckily all the contributors are great so it feels more like a conversation, a two-way street, to narrow it down. If there are certain parts where people think it’s important to include, I would hope I can foster a relationship where they would feel comfortable telling me so.

With the three categories, if the pacing doesn’t feel right I have to re-jig them. If there’s too much focus on one part of the world or too much of one type of feature, the overall balance can be thwarted. My goal is to have these even representations without bias or preference given to any story. That’s why there are no real features in the magazine. There is no emphasis on any culture or experience. Even though the nature of the name defies that. We do see more South Asian contributions because of it. Also the reader audience.

It’s something I have to keep in mind. Despite that connection, it’s not just about that. It’s important not to be tokenistic about the stories. Not to fall into the thinking, “I have too many stories from X, Y, Z culture, now I need more from A, B, C.” It’s a work in progress.

H.Z.:

It’s like you’re growing with the publication.

O.B.:

That’s another thing I struggle with, am I being too self-indulgent? I hate saying that this is my magazine because it doesn’t feel like it, but at the same time I am running it, designing it, editing it. There is that imposter syndrome. I’m working pretty much in isolation and I wonder if I’m being too self-indulgent. Something I have to check in about once in a while.

H.Z.:

I think the recognition that your identity has coloured the publication in different ways brings a tone of caution to your work but isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s evident that the publication has a personality. That there is someone behind the curation and it’s not empty, random or indifferent.

Going back to the South Asian aspect of it, I think growing up I often experienced South Asian culture in a vacuum, and slowly that perception of South Asian culture is becoming more globalized. Chutney contributes to that cross-cultural discourse. How does that tie in with your identity as a diasporic Pakistani who has grown up in multiple cultural landscapes?

O.B.:

That’s like the eternal question. And definitely a big part of why I started Chutney, not necessarily to find myself but to figure stuff out in relation to myself and what role I can play. It’s not just about telling your own stories, it’s about listening to others, and even if you don’t see yourself in them, to find empathy. That will directly have an impact on how you see the world.

Moving around, there is definitely a loss of identity. A lot of Chutney’s contributors feel a similar way; there are a lot of third-culture kids, people moving around, coming from multi-cultural backgrounds and families. The identity struggle is something we can all relate to.

In terms of the force that is South Asia. I think I always knew it was diverse, but the more you read, the more it keeps diversifying. If you pull on one thread, you find ten other threads, and think, wow, the sub-continent is amazingly rich, and has such an important role in the functioning of the world we live in. It’s great that it hasn’t just resonated with Pakistanis, there are people from other parts of the subcontinent who tune in. It’s just nice to see inter-sub-continental solidarity. Growing up it was always us versus them. India versus Pakistan, for example. These identities have always been dividers between us rather than markers of our cultural context.

When you contextualize it on a global scale, it feels like we should theoretically form a big community. This whole idea of the nation-state has dulled down for me. Growing up we were grilled with nationalism and patriotism, but when you’re an adult and interact with others in the global community, I find that kind of fades away. You see the nation-state as a divider rather than a unifier.

H.Z.:

I’ve found that as I grow up, I keep realizing the diversity within Pakistan itself. As a kid, I thought of the country as one monolithic whole, but understanding that 270 million people can no way be the same, and everyone has such a specific cultural background, with so many different faces, traditions, languages, the nation’s borders seem more and more arbitrary. They don’t hold cultural significance, they’re political phenomena imposed on a variety of people.

Chutney’s Issue 3 launched a few weeks ago – purchase here to read the mosaic of stories and experiences Osman has curated.