In the spring of 1955, world leaders from 29 countries gathered in Bandung, Indonesia in hopes of shaping a new vision for their collective futures. Despite being set against the theater and posturing of the Cold War, the diplomatic conference was devoid of Western power players. Instead, this gathering consisted only of African and Asian nations, many of whom were newly independent. The Bandung Conference, the first large-scale Afro-Asian conference, was held in order to establish a unified front against colonialism and neocolonialism by any country, a space created to have conversations about nuclear disarmament and transnational cooperation on their own terms. While monumental as a precedent for Afro-Asian solidarity, the Bandung Conference is often forgotten in a history populated by Western-dominated narratives. The Color Curtain II, a conceptual artist book with a culinary bent, is aiming to change that by introducing new ways of interacting with the past.

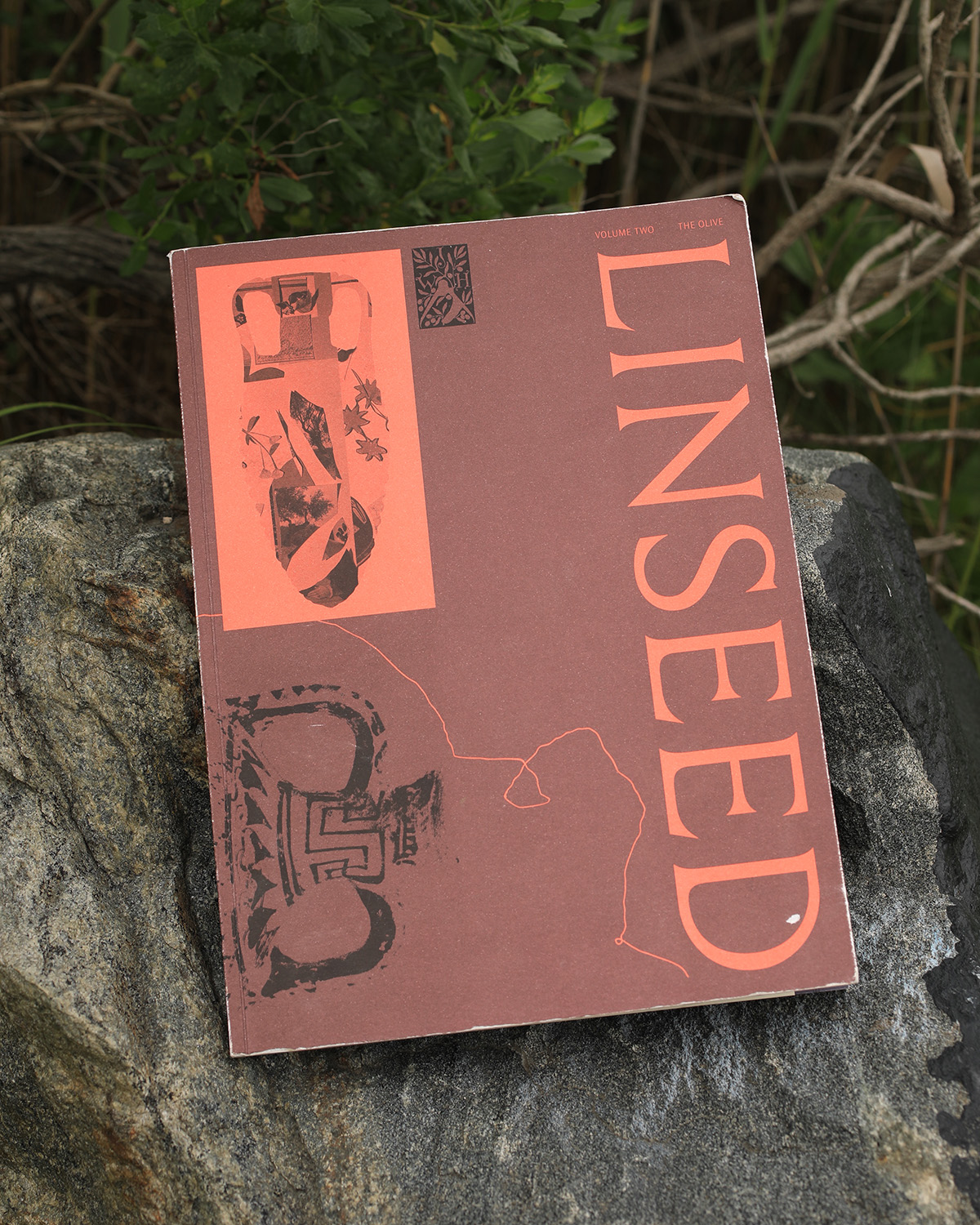

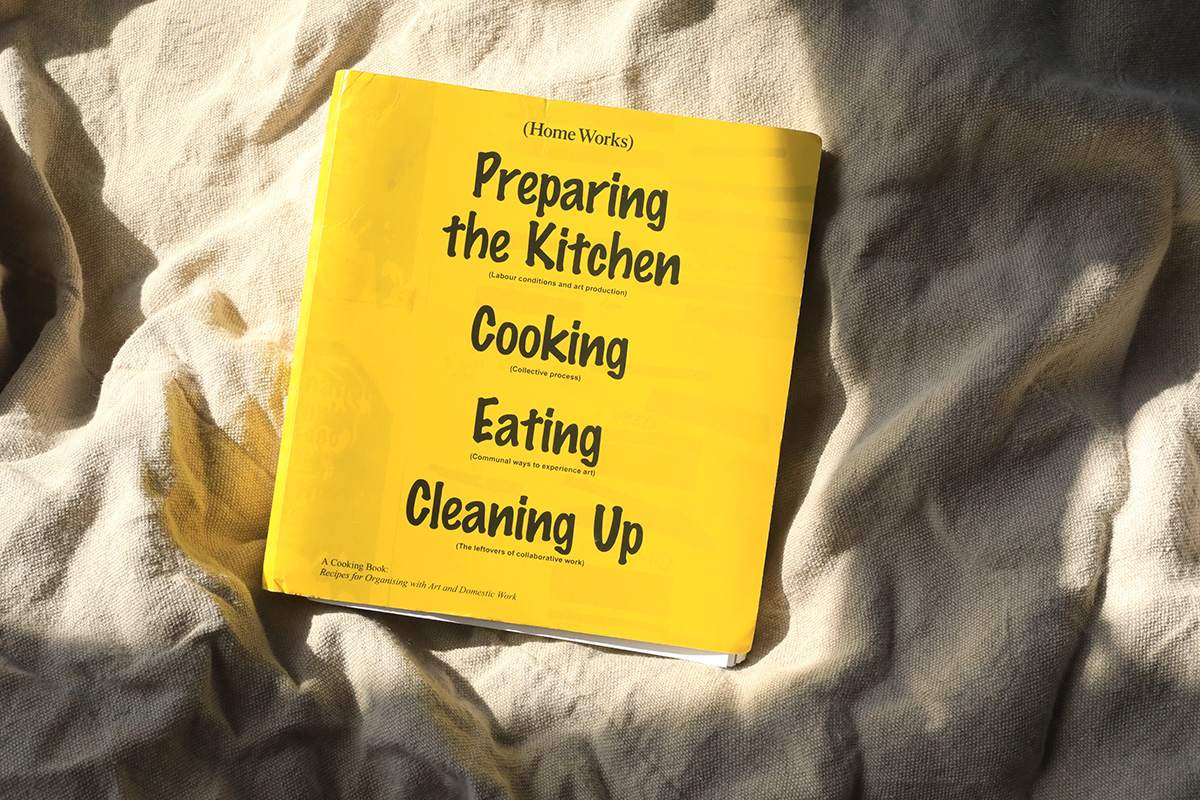

The artist book, which was exhibited virtually by Passenger Pigeon Press at Printed Matter’s inaugural Virtual Art Book Fair this past February, is a continuation of an ongoing exploration of Afro-Asian solidarity by a collective of African-American and Asian-American multidisciplinary artists, scholars and chefs. The project draws its title from the American author Richard Wright’s highly controversial report on the conference in acknowledgment of the collective’s approach to the event from a diasporic lens.

The Color Curtain Project was created by Aerica Shimizu Banks, Desirée Venn Frederic, Adriel Luis, Seda Nak, Tammy Nguyen, Lovely Umayam, and Erik Bruner-Yang, as an attempt to mine the shared experience of food to provide a deeper understanding of how our similarities and differences inform the processes of building solidarity.

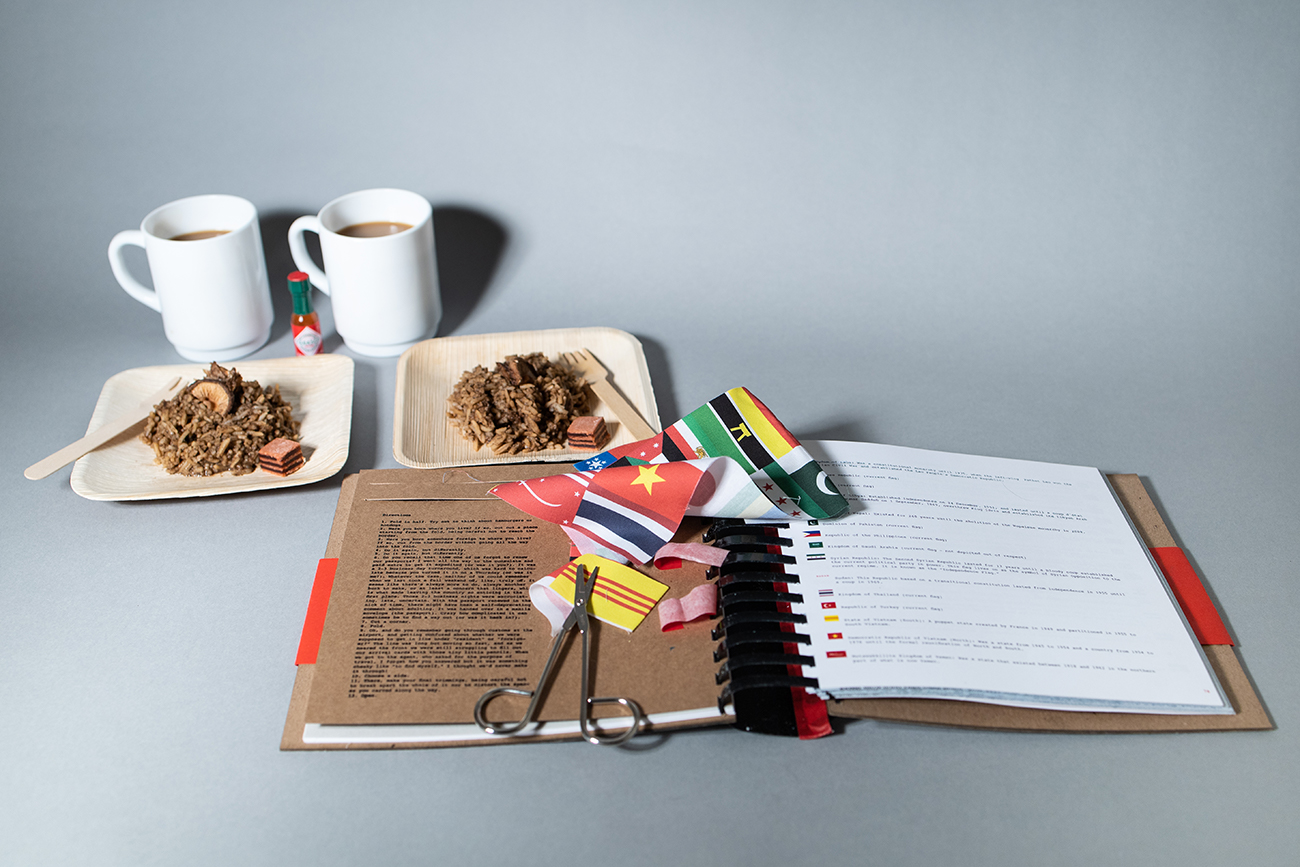

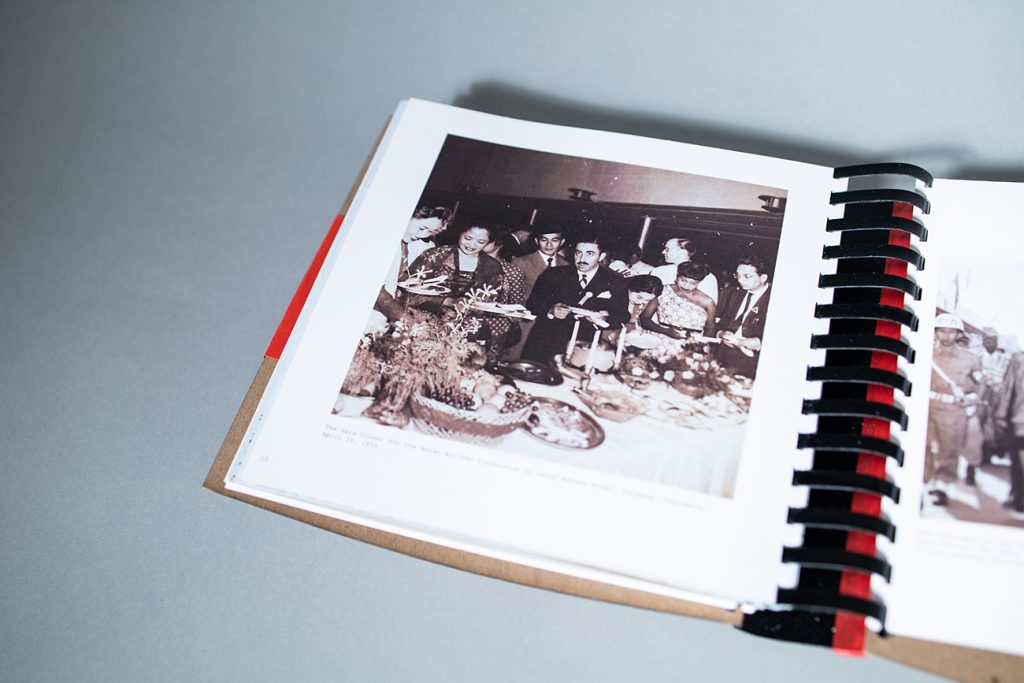

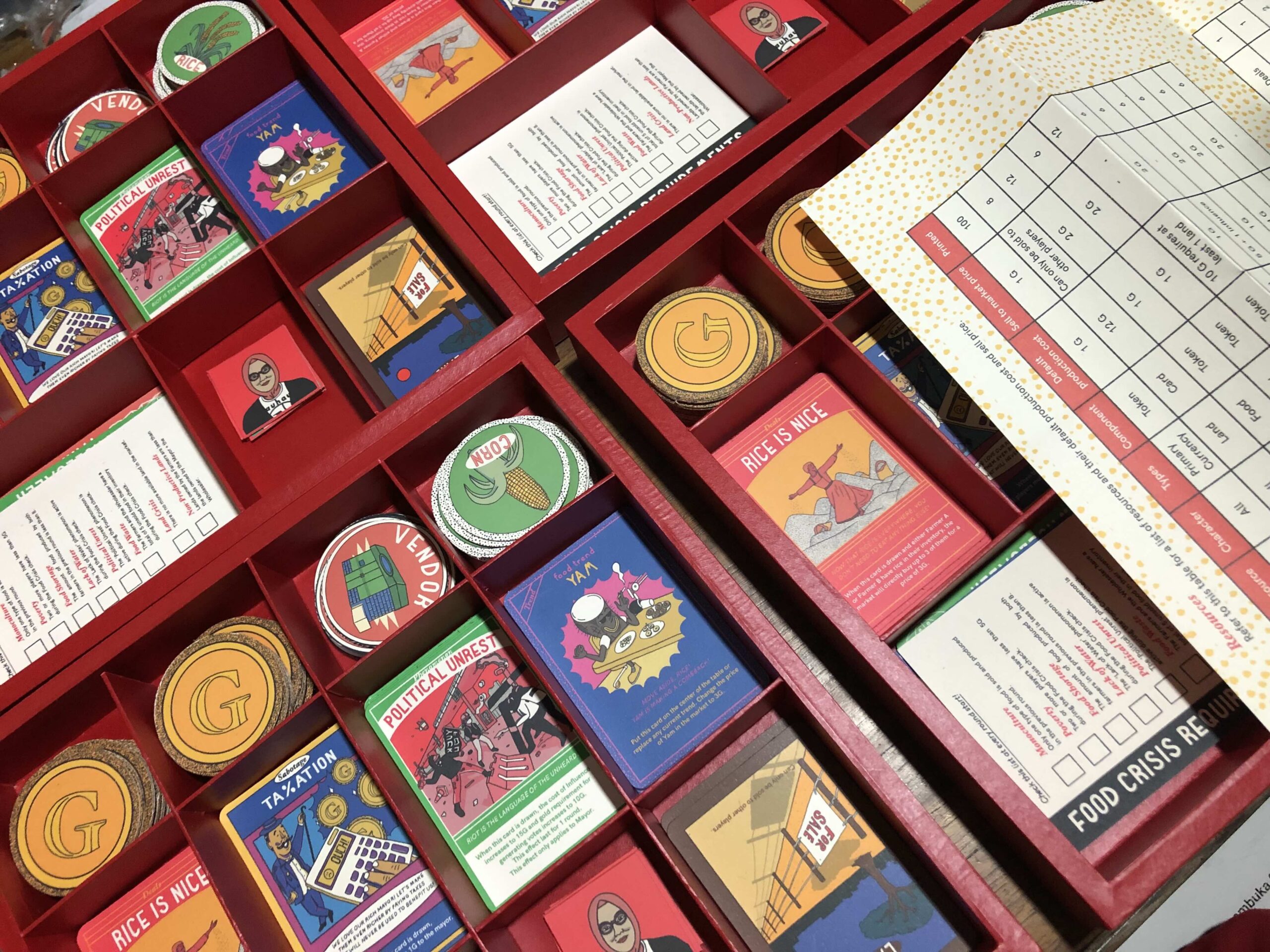

In the project’s first iteration, the collective hosted a lavish dinner party held in homage to the state dinner as a medium for cross-cultural exchange and experience. Guests were guided through the prix-fixe meal by an artist book that contextualized the dinner’s exploration of the flavors five spice, mambo sauce, and ketchup geographically and historically, and were invited to collaborate with fellow diners on interactive activities.

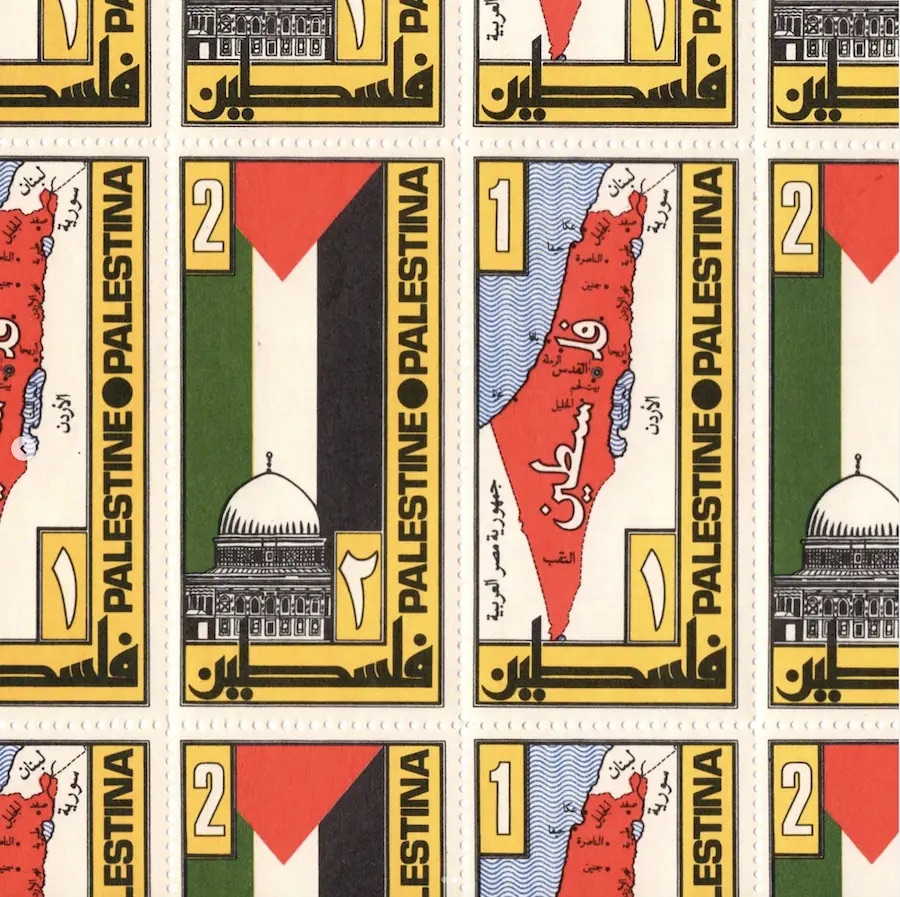

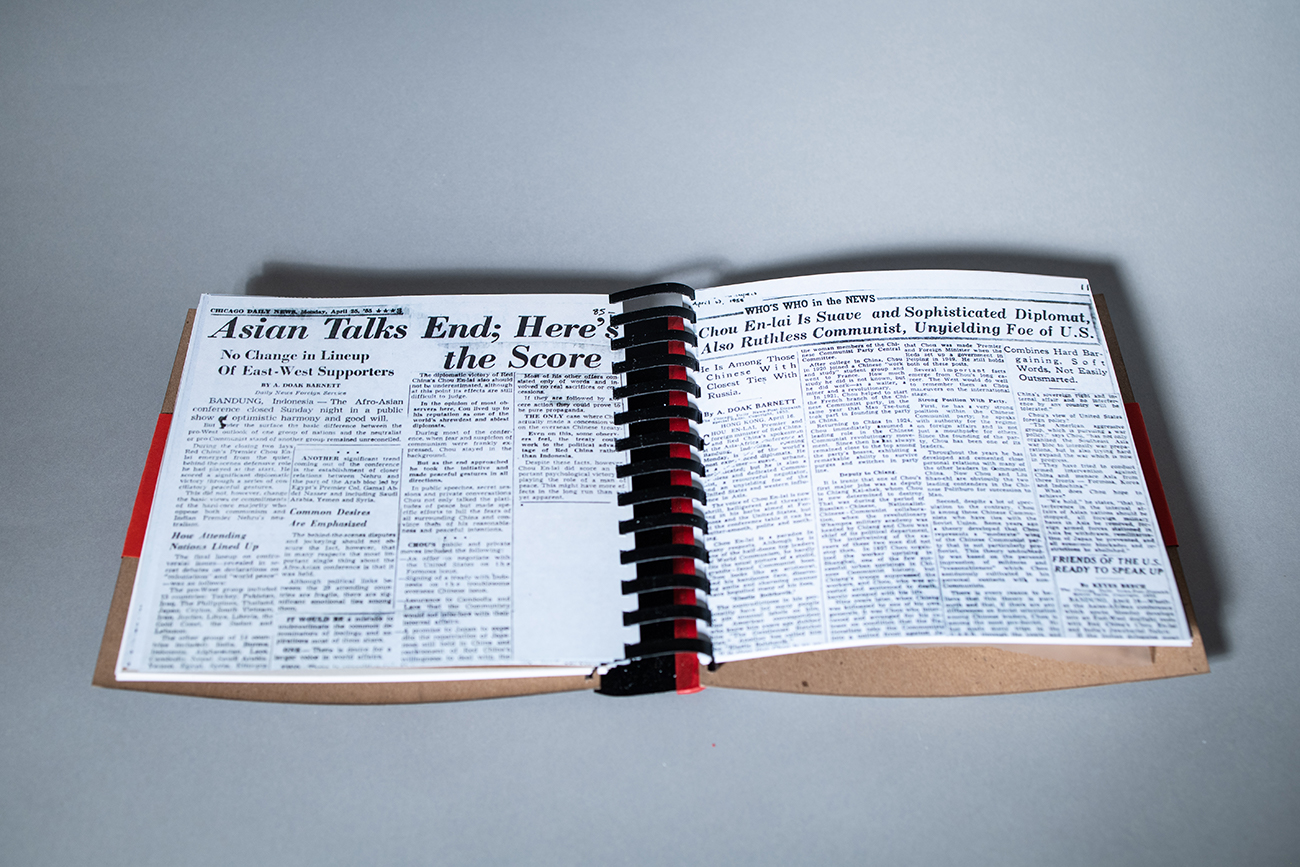

While the pandemic has rendered such extravagant gatherings impossible for the foreseeable future, the second installation disseminates the project’s efforts into a personal meditation to be experienced at home. Color Curtain II introduces the Bandung Conference through excerpts from Richard Wright’s report and newspaper clippings and photographs on the event, with essays and manifestos by collaborators interspersed throughout.

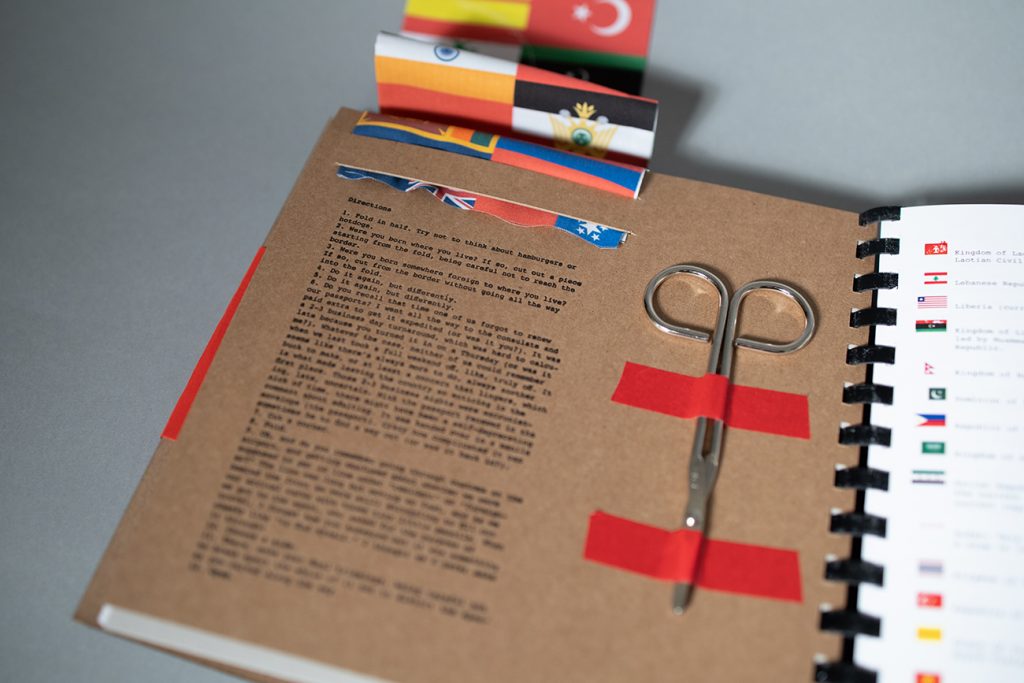

The book comes with tactical activities like an MRE (a military field ration that is an abbreviation for meal, ready-to-eat) for the reader to cook, a crossword, and a paper-folding exercise. These interactive prompts, which range from an exploration of the experience of crossing geographic borders to the incredibly specific crossword clue “the sound an aunty makes when sucking her teeth,” draw from a well of shared diasporic experience in order to point towards commonalities.

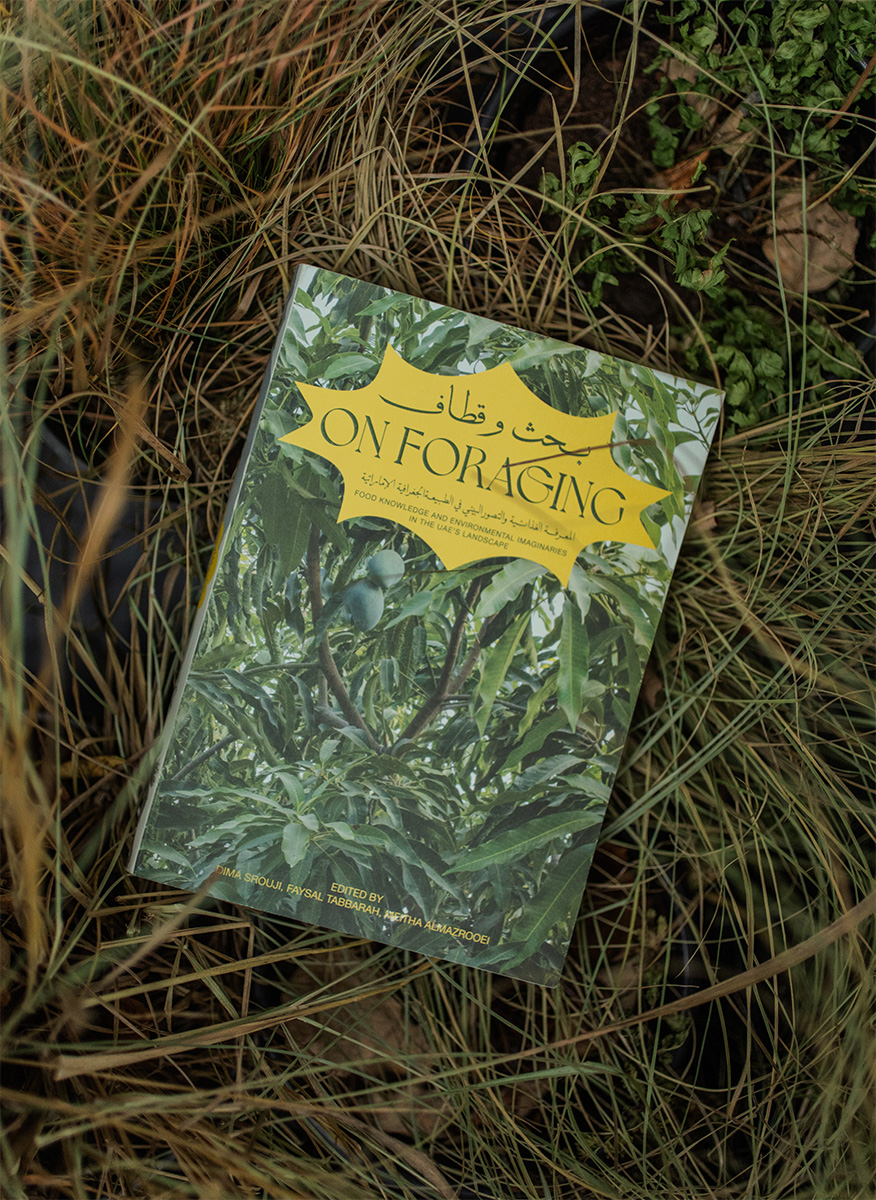

Color Curtain II facilitates a blurriness, promoting an inconclusivity around how we define identity that in turn creates space for thinking about solidarity. Tammy Nguyen, an artist and the founder of Passenger Pigeon Press, points to the project’s culinary experiments as an example of this. “A lot of cuisines and their spices are understood in relationship to the geography of where the food is from. Five Spice is one of the spices or flavor profiles where it’s like, ‘Oh that’s Chinese food.’ But is it? It’s literally the same ingredients as many African ingredients. In the MRE there is a packet of five spice, dried mushrooms, and dried fish. What [chef] Eric [Bruner-Yang] is trying to do with that is to try to take away the names of those items so that the final product is a dish flavored with ingredients that are no longer bound to their geography.”

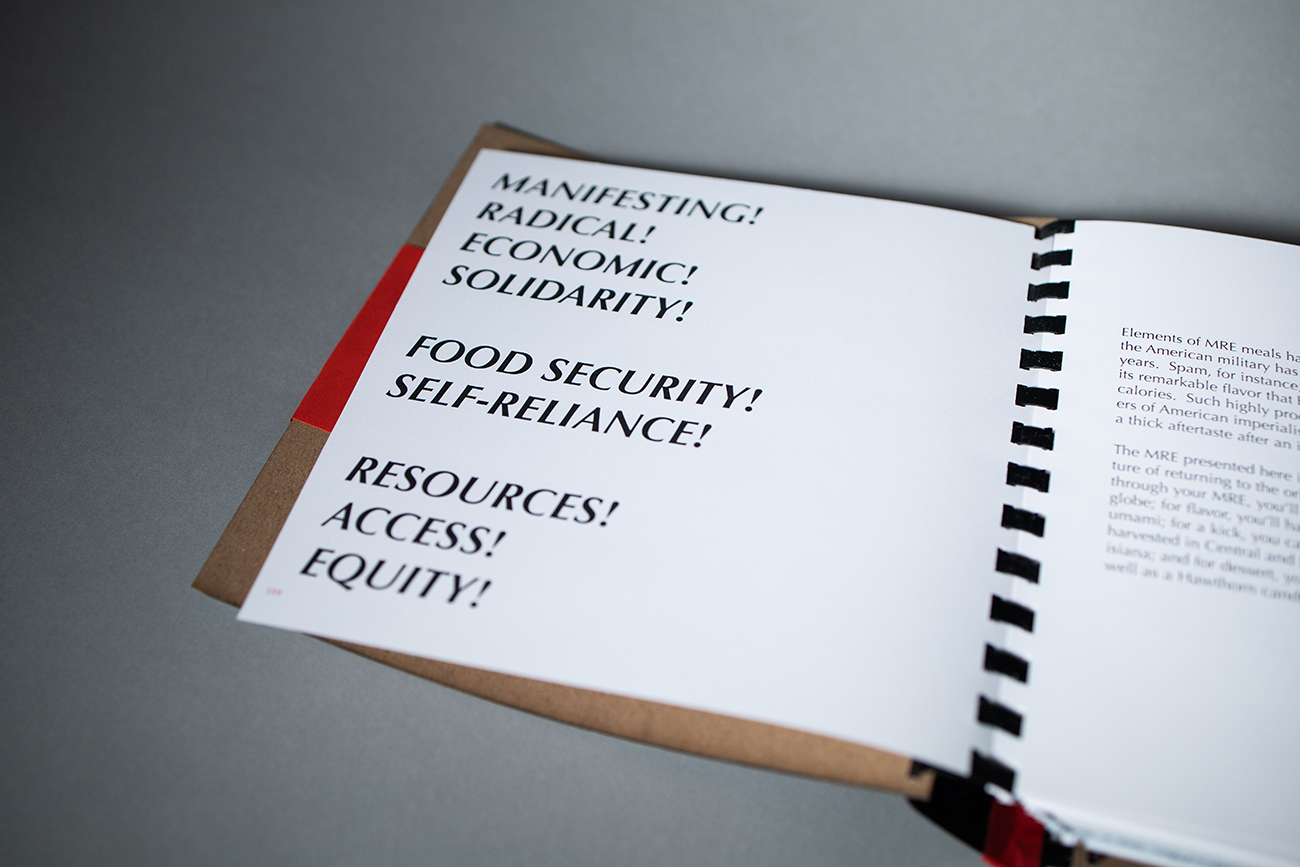

Recent acts of violence against Asian-American elders have elicited calls for solidarity against the perpetuation of hatred and fear in our communities. These echo similar calls that spread across social media during the Black Lives Matter protests held in response to George Floyd’s death. Often used in the context of social media infographics, what escapes the short and eye-catching medium, which has transformed ‘solidarity’ into a catch-all term, is the means to go about it.

Building solidarity is no small task. Nguyen acknowledges that part of the reason why the Bandung Conference is overlooked as a historical event is due to its failure. The Conference dissolved because the needs of individual participating nations eventually took precedence over the Conference’s aims for cooperation, “Solidarity is needed more than ever. But it’s very hard work, it’s almost exhausting work, that carries a high risk of giving up. [At the core of it] it is exhausting to care about people who are different from you.”

Color Curtain II aims to provide a playful and loving way to emphasize how difficult solidarity is while highlighting that we have more in common with each other than we think. For Aerica Shimizu Banks, a diversity consultant and collaborator on the project, it is worth it to do the difficult work of excavating an often painful past in order to move toward collective liberation. “These crises of white supremacist violence and crumbling capitalism converge on a horizon of hope. Amazon workers are unionizing, Oakland community members of all races are accompanying Asian elders on their walks around Lake Merritt. These are examples of ways we build solidarity in this moment. The Color Curtain Project is an offering to the memory of past multicultural solidarity movements to inspire new ones.”