The artist Rajyashri Goody maintains a deeply poetic and subversive catalog of both Dalit resistance and caste-based violence through her artistic practice, playing with non-existent archives, cookbooks, memory work and a personal exploration of lived experiences. Central to Rajyashri’s practice is the Dalit connection with food. While researching Dalit food histories, Rajyashri found that there were little to no records or recipes documenting the group’s rich culture around food. In response, she has sought to reconstruct and build new archives around the topic, incorporating various mediums that span text, voice, paper pulp, ceramics, photography, printmaking, video and installation.

Her work tells the story of Dalit liberation by converging narratives held within elements like food, land, language and literacy— all of which have served as integral tools for enforcing caste rules across generations.

What does food have to do with caste? Caste in South Asia pervades all aspects of an individual’s life – a person’s last name, how a person pronunces words and what dialects they use, all the way to one’s diet can all be ingrained markers of caste identity. Today, barely any Dalit cookbooks exist. This in part due to willful omission and in part due to neglect. As illustrated by her memorable solo Is The Water Chavdar at SKE or her ongoing record, Writing Recipes, Rajyashri’s work not only highlights these tensions but also uses materials, metaphors and an insightful sensibility to refuse and reclaim them. Reinforcing the point that food is political, Rajyashri examines how oppressive systems can take hold of our relationships to diet. In doing so, Rajyashri also surfaces stories of resistance.

In my interview with Rajyashri we unpack the many modes in which caste-based stereotypes and violence are disseminated. We talk about how she uses food to interrogate the political dimensions of caste, the caste system’s roots in land and agricultural cultivation, as well as the power dynamics and relations certain foods embody on the Indian subcontinent.

Somnath Bhatt:

Rajyashri, how did your interest in food start? How do you translate that into other visual media?

Rajyashri Goody:

Food has been a big part of my life since I was a teenager, but a particular interest in food archives, specifically Dalit food archives, began in 2016, when the beef ban in India led to a number of horrific lynchings of Muslims and Dalits by local ‘Gau Rakshak’ ‘cow-protectors’, on the suspicion of them eating beef. This, accompanied by assumptions by non-Indians that as an Indian I was vegetarian, led me to learn more about my own family’s and community’s relationship with caste. I was particularly interested in our relationship with beef at first, particularly because as people from the Mahar caste, many gave up the eating of beef a long time ago on the instructions of our leader Dr. Ambedkar, to leave behind all the signifiers of our caste. Our move towards vegetarianism has not been one of mimicking Brahmanism, but that of following Buddhist principles.

Initially I was keen on finding Dalit cookbooks, and it was the lack of them that led me to continue to build on my research, through literature, writing, ceramics, photography, and now, more often, performances and readings.

SB:

Food is often seen as the substance that brings people together. In South Asia, though, it is also used as a tool of segregation. How do you explore this dichotomy in your work and research?

RG:

My research lies in the relationship [between] caste and food, particularly the Dalit experience of food and water. In order for caste to function ‘properly’, every aspect of a person’s life must be governed by rules that ensure separation and deny the possibility of intermingling of people from different castes. Extensions of these rules apply to food too. For instance, people from different castes are not supposed to eat together, for the higher caste will get polluted. Certain castes are known only to eat certain kinds of meat, whereas some are known to be vegetarian. I’m interested in how something as seemingly intimate as our food habits and preferences are often completely out of our control, governed by caste.

Apart from my own family stories and archives, I look towards Dalit literature to learn more about food and caste. Every Dalit memoir I have come across is filled with stories related to food – hunger, feasting, begging, stealing, hunting, foraging, cooking, sharing – endless experiences that shine light on how deep the roots of caste go. Based on these, I build ‘recipes’, make ceramics, and gather photographs.

SB:

What are some noteworthy memoirs that have influenced your work?

RG:

Every Dalit memoir I’ve read has offered me so much that it’s difficult to pin down a few. Namdeo Nimgade’s In the Tiger’s Shadow was incredibly moving, as well as Daya Pawar’s Baluta and Strike a Blow to Change the World by Eknath Awad. I keep turning back to Babytai Kamble’s The Prisons We Broke and Urmila Pawar’s Aaydan, not only because they are beautifully written but as I keep rereading them I’m constantly finding new ways of thinking through certain themes within Dalit culture. I’d like to also mention and Untouchable Spring by G. Kalyana Rao, that calls itself a memory text, rather than a memoir or autobiography. Since many of the writers I’ve read are the first generation in their families to go to school, to read and write, it’s fascinating to understand what they write about, why, and more importantly, how. The line between fact and fiction, truth and dreams in a book like Untouchable Spring is blurred, gathering stories from ancestors long gone, from pasts never documented, and yet that is exactly what makes it a strong ‘memoir’ to me.

SB:

I love your use of vernacular and etymological food metaphors. Could you share some of the most useful ones that have aided your thinking?

RG:

My favorite remains ‘Bhaakar’, or bhakri, a thick millet roti.

‘Bhaakar is as large as man, bhaakar is as infinite as the sky, as bright as the sun. Hunger is bigger than man, more vast than the seven circles of hell. Man is only ever as big as bhaakar, as big as hunger.’ This is a loose translation from Sharankumar Limbale’s autobiography Akkarmashi, originally in Marathi.

I came across it early on in my research of food and caste. I too grew up eating bhaakar. I detested it as a child, preferring softer chapatis instead. But Limbale’s quote seemed to pull everything together for me – the circle of the bhaakar, deep hunger, our caste identity, my subconscious shame, rejection, generations of pain and dignity. It’s difficult for me to put it in the right words, but it’s really because of this quote that I began to make ceramics of food, specifically the bhaakar.

SB:

What draws you the most to the format of a cookbook? How does it contextualize larger socio-economic dynamics?

RG:

On the surface the cookbook’s format seems ‘democratic’, an easily accessible form of writing, it is even practical or productive, for one is expected to make something from a cookbook. But many cookbooks also assume many things that are privileges in a caste-dominated society. One is that of literacy.

Until a few centuries ago Dalit people were not even allowed to listen to ancient mantras, let alone enter a school. Even now, the rate of literacy and graduating from schools is still considerably low, even though education is at the center of every Dalit family’s aspirations. If one isn’t allowed to read and write, how is one able to put down recipes in pen and paper?

Another assumption is that one has a stocked kitchen with appliances and ingredients, and given the history and socio-economic status of many Dalit families, this is almost an insult. Another important point is that the traditional cookbook assumes that by cooking a dish from it, the reader can experience, literally consume, another person’s culture, a specific time in history, or a feeling of home.

My cookbooks aim to break these assumptions. I rely on extracts from Dalit autobiographies, most of them from the first generation of literate people in their communities, and I don’t date them, specifically to play with the notion of time, the past, present and future. I twist the extracts into ‘recipes’, where the reader is following instructions, but the end is often inedible, pointing towards an experience that perhaps can be felt at a certain level, but simply cannot be consumed by the reader.

SB:

The folio Eat with great delight invokes a past of care and nurturing; I want to ask you what other sensory dimensions these photographs evoke for you?

RG:

Eat with great delight is a collection of family photographs, taken by my parents in the 80s and 90s. They are an extension of the cookbooks I make, bringing in my own memories of food. Owning a camera, like learning how to read and write, is a matter of access, and it was only when my father, originally from the UK, joined the family, that we were able to build a large collection of photographs. Before that, apart from a few studio photographs, we don’t have any images of my mother’s side of the family. I don’t know what my maternal great-grandfathers looked like.

That’s why I wanted to bring these images into focus, because though they were originally meant just for our family’s eyes, I believe they hold space for a complex understanding of Dalit culture. In the end, they are just happy family photos, taken on occasions of celebration, of laughter, of joy. Food is a part of all of them, and these experiences of food are just as important as those of hunger, shame, begging, leftovers and pain. Accompanied by the cookbooks, I believe they add to a somewhat whole experience of our lives. I would like them to be taken as just happy family photos, invoking a sense of nostalgia even from a viewer of a different community, a different caste, in order to humanize our Dalit experience.

SB:

Are there specific historical or contemporary events that have influenced your art?

RG:

Definitely. There are three dates in particular for me. 1927, the year of the Mahad Satyagraha, where Dr. Ambedkar led thousands of people to drink water from the main water tank in the town of Mahad, and subsequently, a few months later, burnt a copy of the Manusmriti, the book of law. 1956, when Dr. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism, as a result of which so many from the Dalit community are now Buddhist, including my own family. The year of 2016, the year of the Una protests, which is where a group of young Dalit men were publicly lynched for transporting a dead calf. That violence, as well as the public outcry and protests that followed, left a big mark on me, leading to this journey into Dalit food practices.

SB:

Caste is also directly tied to one’s ability to own land and ultimately grow and cultivate food. Can you broaden these material considerations and its impact on your work?

RG:

Owning land, growing and cultivating food, is something that was not allowed for Dalit communities. For generations, Dalit people have been made to work on others’ fields, cultivate their crops, and live on the small share of that crop for subsistence. There are certain areas of land that were donated to Dalit communities hundreds of years ago, but this land is often only fit for grazing.

This denial of land rights is at the base of the Dalit experience of food, restricting one’s diet, forcing people to depend on begging as a caste-based practice, relying on ‘joothan’ leftovers and the ‘generosity’ of upper-caste people, waiting patiently for someone to give one water from their well, hoping that the farmer will give you more than just the husk of the crops as your share, wait for an animal to die in the village to get much needed nutrition from its meat. For some people, this has also led to them being labeled thieving communities, stereotyped as stealing [or reliant on] stealing as a form of survival.

SB:

If food is political; how do you frame the notion of ‘taste’ both as an aesthetic tool of division but also as a casteist or a classist framework used in visual art ?

RG:

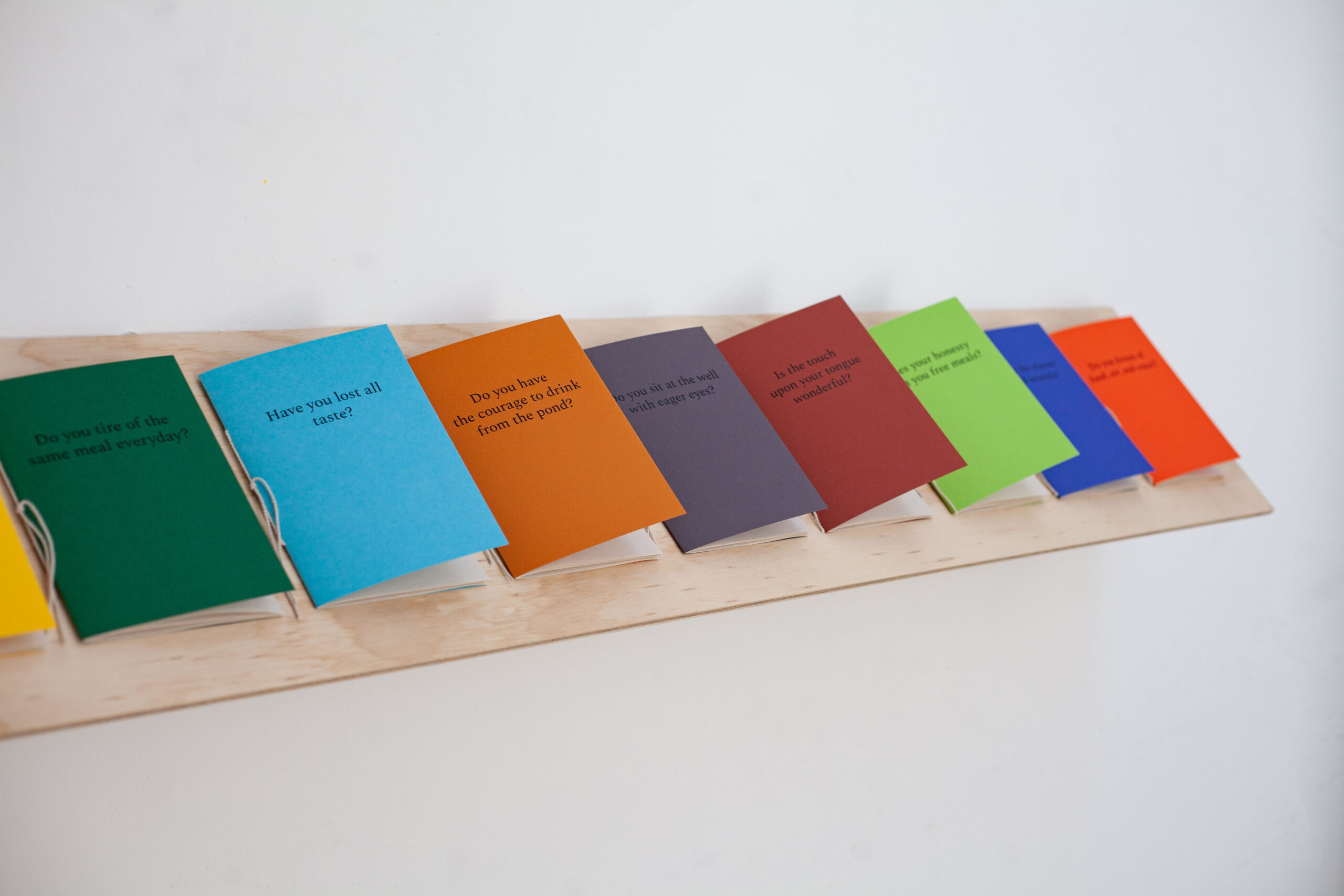

Playing with the notion of ‘taste’ is at the heart of my practice. Whether it involves creating sort of harmless looking colorful A5 booklets to lure the viewer to pick up and read recipes, or blowing up family photographs in a white cube space, or making ceramic objects that may not be particularly skillful or even ‘beautiful’, but catch one’s eye in some way.

On one hand, my own tastes, my hold over language, as well as my very limited craftsmanship over any material, play a big role in the aesthetics of my work, but once able to access a space that already has an existing framework, that perhaps I’m not entirely comfortable in, it’s an interesting challenge to attempt to transform it in some way, to bring full attention to what I want, as opposed to what someone else would.

SB:

Are there any transnational artistic and political movements with which your work shares any connections?

RG:

I find a lot of inspiration from Dalit political and religious movements in India, having grown up in them. I’m part of the Secular Art Movement, based in Maharashtra. I have also been part of the Vaanam Art Festival a few years ago, organized by Neelam Culture Centre in Tamil Nadu, and I find their work incredibly important. Outside of India, it’s difficult for my work to share any particular connections with movements, but there are specific artists, writers and academics from all over the world that help me make sense of my practice.

SB:

What is something you are looking forward to working on next?

RG:

I still continue my work with food and water, but over the last few years I’ve become very interested in my community’s conversion to Buddhism, and how that has shaped my relationship with the idea of movement, travel and pilgrimage, a renewed understanding of landscape. I’ve been using paper pulp a lot, to create these landscapes in some way, porcelain, sound, and ordinary objects like bowls. I’m currently in France researching patriotic porcelain and speaking ceramics, which became popular after the French revolution, and trying to see if there are some connections I can draw with popular imagery in the Dalit movement, for Ambedkar drew many threads between Buddhism and the French Revolution. Seems a bit ambitious, but let’s see.

Special thanks to Dee Sharma for contributing research to this piece.