As unprecedented events continue to unfold almost daily, being able to discern what is fact from fiction has become increasingly important and at times, lifesaving. And yet, there is a culture war being waged on both science and fact by misinformation, particularly when it comes to information surrounding the environmental crisis. The global scientific community has made it clear that climate change can largely be attributed to human behaviour, and we are running out of time to stop it. However, climate change deniers with ties to fossil fuel industries, governments across the world and media continue to sow seeds of doubt, obfuscating the scientific realities of climate change and making it so that urgently needed progress cannot be made. At times, it is a grim picture. Baker-turned-glacier-guide Rose McAdoo is trying to combat that through her educational cakes and desserts that explain the natural processes behind glaciology and climate change. For these cakes, Rose, who splits her time between the North and South Poles, draws from her experience both as a baker and as a glacier guide.

Rose first began her career as a baker, baking sweet treats for weddings and birthdays before she turned to cakes as tools for activism. Since 2016, she has made desserts and edible projects that are used as visual aids in workshops and events to highlight the impact of climate change. She has also created cakes with the intention of catalyzing conversation surrounding wider topics such as the refugee crisis in Africa and the U.S. prison system. Earlier this fall, I interviewed Rose about her work and methodology and what her aims are for the future of cake and climate change.

Julia Georgallis:

I’m really excited to talk to you because as a fellow baker I’ve been following you for a little while. You’ve got a really large body of work. As an introduction, could you talk me through your career so far? What are you working on at the moment?

Rose McAdoo:

It’s definitely a wide body of work because it has mirrored my career path, which has been long and diverse. I started working in food when I was 14 years old; [I’ve done] everything from running restaurants to working in bakeries to executing large off-site catering events. Eventually I landed my dream job at Nine Cakes in Brooklyn and that’s really where I learned a lot of the skills that I use now. I worked there for 4 years creating high-end wedding and celebration cakes before taking a job offer in Antarctica in 2018. I worked as a chef down there for two seasons before gaining a position on the Winter Search and Rescue team during covid. That allowed me to pivot my pastry career toward the outdoor industry and the sciences. To keep those skills fresh, I spent my last three summers working as an ice climbing glacier guide in Alaska. I’ve just finished my third season as a glacier guide and Alaska and Antarctica are the two areas where I focus my work now. I’ve spent the last four years exploring how to continue producing creative cakes while shifting my full-time profession out of the kitchen. I’m now managing to work outside, explore new opportunities that I love, and learning a ton – then I’m using cake design to tell deeper stories about what I’ve found most intriguing or astonishing. It feels very full circle but I can assure you it’s taken a long time to get here and it’s definitely been a challenging, non-traditional path.

JG:

I think those non-traditional paths take a lot longer. They’re more wiggly and you have to have a lot more confidence to just go ahead and do it!

RM:

Yeah, I definitely doubted myself and on various points of that journey but looking back I can now see how it all fits together. I’m still deeply involved in food but I’m now better educated with more personal experiences in our world and the environment.

JG:

How has your own story influenced your work?

RM:

Exponentially. My career path has exclusively followed my own interests and curiosity. I wasn’t able to afford more than a year of college, so I ended up working in the industry straight away. Over the years, my pastry work has become the lens I use to get curious, so my art and my food process has really followed my own learning journey and lifestyle. It’s vital to my practice that I only make work about topics in which I have first-hand connections or experience, so that really challenges me to go further than just reading an article and making a cake – but to instead go and spend time in a place. Building relationships and meeting the people and scientists whose work I’m communicating makes my storytelling more impactful – for me and my audience. For example, after spending three full summers on one hunk of glacial ice, I can better explain the rapid changes that are happening. I have an emotional attachment to those changes. There is a personal connection. There are real, raw feelings. There is a timeliness.

JG:

Why did you make the jump from pastry and cakes to activism, communication, and working in the field as a glacier guide?

RM:

Working in kitchens is exhausting with crazy hours and very little to no time outside. It’s my favourite career path – I loved it – but after 14 years I wanted to be back in a forest, on a mountain, shivering in the wind after dipping in an alpine lake. In one-room basement kitchens with no windows, I craved days, weeks, months of hiking and adventuring in the wild. Amazingly, the cake shop I worked at in Brooklyn had a huge floor-to-ceiling glass facade that overlooked the Statue of Liberty. I remember one night in particular, I was daydreaming in that commercial kitchen about how incredible it would be to take big cakes out into the mountains (maybe in my backpack?!) and make wedding cakes on-site for elopements. That daydream was aptly timed with the 2016 political shift in the United States. I was angry about everything that was happening in the country politically – from climate change naysayers to stands against refugees/immigrants and fights about gun control. That was really the jumping-off point where I wondered whether I could make cakes about other subjects and then use those cakes to communicate a bigger story. Could I highlight shared values and visualize the world that I wanted to see? So I made a dessert collection about those topics in 2016. That project gained a lot of traction and landed me my first-ever round of press. I wondered if I could keep pushing this idea. Eventually, this concept of cake-as-communication was all I could think about, so I applied for and accepted a job cooking in Antarctica in 2018. Immediately, I saw the insane amount of passion, dedication, time, knowledge, and resources it took for research teams to work in polar areas and communicating polar sciences quickly moved to the forefront of my pastry work.

JG:

On your website you use this phrase about how food makes big topics more digestible. It seems like a kind of manifesto of yours, what does that mean to you?

RM:

I think curiosity comes down to accidentally being interested in something. If you’re curious, your guard is down and your sense of wonder has kicked in. I think that by using dessert as an unassuming medium for storytelling, people’s guards are down. They’re not necessarily expecting to learn something challenging so it’s actually an easy opportunity to showcase a research project about a microscopic zooplankton that no one has ever heard of or to teach people about how glacial crevasses are measured out in the field. Because we’re not in a museum or a lecture, we don’t have our notebooks out. No one’s prepared counter-arguments. No one’s expecting to need a strong opposing viewpoint. We’re just looking at a cake or eating a candy bar – having fun. It’s an easy way to introduce new ideas and visually explain confusing or inaccessible concepts. As a glacier guide, it’s easier for me to understand the science of ice falls if I think about their dense layers as a candy bar. And if it’s easier for me, I’m sure it’s easier for everyone else. So that’s vital to my dessert work at this point. I think if you can get people curious and if you can catch them off guard, educating is easier from there.

JG:

Because no one’s afraid of a dessert are they?

RM:

Exactly. We’ve been conditioned our whole lives to think that data is boring and – for that matter – that cakes are exciting, so it’s a great way to highlight topics that people may not be interested in initially.

JG:

What is the relationship, do you think, between food and science?

RM:

You can’t separate food from science – from caramelization, gelatinization, and emulsification to food processing, preservation, and ingredient manipulation. Beyond food science, we can use food to break down how science works. It’s been really cool as I’ve worked with scientists in the field or attended lectures to hear researchers using dessert analogies to make their studies relatable to a larger audience. A geologist in Antarctica explained that looking for fossil pieces after all the tectonic plates shuffled the evidence was as chaotic as looking for a grain of sugar in a dropped piece of cake. A team member in Washington talked about how everything is interconnected in our world before comparing biodiversity/extinction to removing an ingredient out of a cake and expecting the same results. If you leave out flour or baking soda, that cake is going to look, feel and act very differently. In the same way, if you move one species from an environment or if you remove one piece of the glacier formation equation, it doesn’t necessarily still work. Every ingredient has to be present in nature to maintain homeostasis.

In short, I’m always curious about what the world would taste like. I think of our planet as an edible canvas. For example, what would a rock taste like? What flavours would microscopic creatures like tardigrades prefer – salty, sour, sweet? How can we represent rapidly changing data sets with pastry? How do you sculpt the cross section of a glacier volcano out of fondant? As I learn, I’ve found that my brain explains topics to me by quickly visualizing new information as desserts. Making that intersection between food and science is really fulfilling to me – despite its dramatic challenges in the field.

JG:

It’s a great way to learn. Before I started baking, I didn’t think I was very interested in science and then realised that baking was basically biology and maths! If we were just taught with food, probably everyone would like maths.

RM:

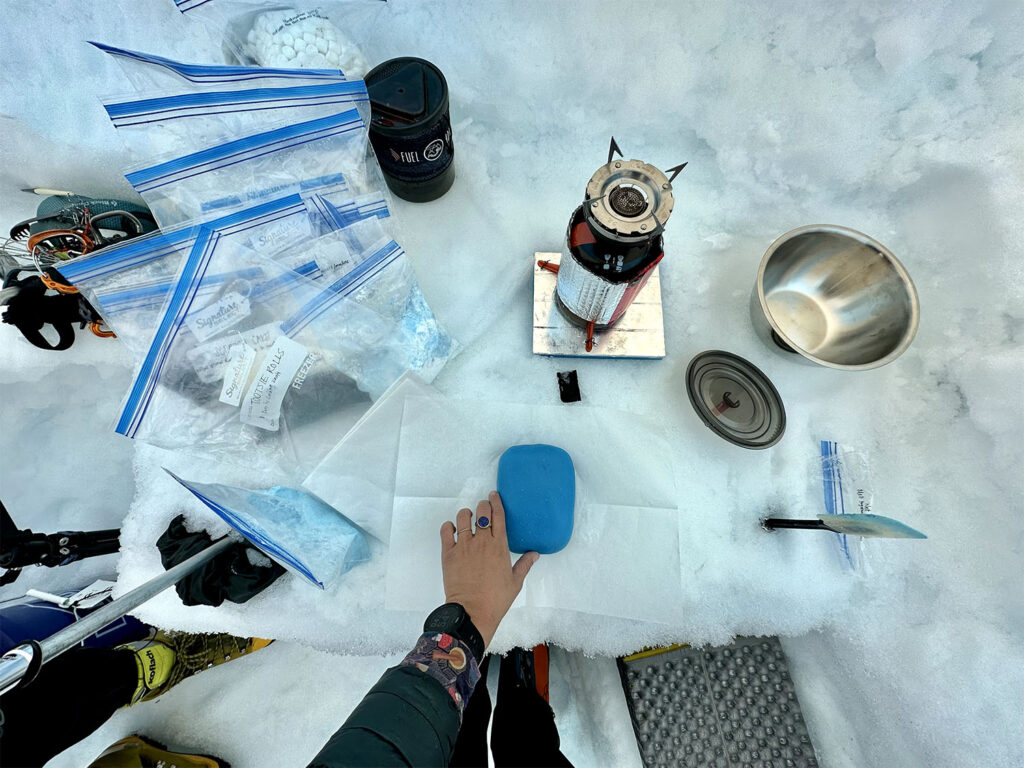

When developing an initial idea, I’m always following my own curiosity. It’s important to me to build lasting relationships through the work that I’m doing, so my projects are often long in scope (I’m currently in the third year of my glacier outreach work). I have new ideas percolating but I can tell that I’m not done with ice yet. Over the last three years – as the artist in residence with the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project, guiding on multiple glaciers on the Alaska coast, making glacier desserts at Denali Base Camp, and crafting 200+ glacier dessert boxes – there have been lots of individual glacier-based projects that all fall under a bigger, overarching learning experience. My creative process is made up of seven steps. The first is simply allowing myself to wonder and get curious. What do people have false understandings about? What is exciting and timely? From there, I try to learn as much as I can by reading articles, following people online, listening to podcasts, watching videos, looking at other art mediums (ceramics, paintings, etc), and taking in as much information as I can about that topic. Then I go and experience it in person. If I can participate in some of the scientific research, I will always try to do that. Participating builds deeper personal relationships than simply observing and gives me the chance to ask lots of questions and gain a more holistic understanding of the immense time, money, effort, training, and resources it takes to accomplish scientific goals. I sketch out drafts, pack my ingredients and tools, and beta-test a lot of recipes in the field. I’ll make test batches of things and photograph and film the process as a backbone for the project later. (I often use those photos and recipes for much bigger events later.) For example, the glacier dessert boxes that I shipped all over the country were all recipes that I tested out on glaciers. Once I’ve learned and experienced the place, I wait. The waiting originated from having to work full-time while managing all these projects, but I’ve come to learn that time away deeply shapes my work. Not sharing my stories immediately helps me sort out what I’m excited by and what resonates with my audience – as well as identify which moments I keep coming back to and choose favourite photos and clips. Finally, I start to create. At this point, I go into a sort of manic flow state for a few days and produce nonstop – typically a full cake collection. I stay up super late and get stressed and troubleshoot and pivot and have such a blast with myself and my creative ideas. It’s wildly fulfilling to have this long relationship with a project and then finally produce the cakes or desserts that I’ve been imagining for months. The final stage is to share the work: appearing on podcasts, writing articles, booking speaking engagements, and posting on Instagram.

JG:

What’s next and what impact do you want to have with your work?

RM:

My goal is to be on location, working in the field with scientists, as a field assistant and storyteller for their research. And then, I also want to be public-facing. I don’t want to just be in the background doing this work, I want to be able to share this work on a larger scale with art museums and organisations and venues together that maximise the storytelling. I think that scientists are an incredibly passionate group of people but they have to do so much work to get their work done in the first place they often don’t have time for the sharing part of that. Which is such a disservice to their work because, like I said, it’s years and years of research and grant-writing and project development and studying to figure out what you even want to research in the first place. [I want] people to have fun and engage with science, especially right now. Science is being vilified and questioned and doubted. I want the sciences to have a bigger platform and I want scientists themselves to have a space to speak about the work that they’re so passionate about. As for the impact part of it, I’m definitely starting to see some of the fruits of my labours after 6 years, but it’s been really challenging for my work to be seen as a legitimate science communication tool. I want my impact to be reframing the notion that cakes are a cute hobby or pretty wedding decoration. I’m starving to use my work as this legitimate communication tool and as a driver of understanding. A lot of grants for science research mandate an outreach plan and I want my work to be seen as a real tool for doing that. As far as impact, I want to encourage other people to use whatever weird interests they have to do that too and I think there’s a lot of power in using things that people don’t expect or understand to talk about important topics and I’m seeing that more and more. There’s dance shows to be used to communicate Antarctic glacier melt, for example. Art is becoming a little more esoteric with social media in terms of people being able to get their work out there, but I want cakes to be a big part of that story.