Today, little thought is given towards the humble napkin. They are useful, of course, and we will always request a serviette if none are to be seen. But we take little notice of how they appear on the table — we might not use them at all when eating at home. Meanwhile, disposable paper cloths are thrust into our hands at cafes or take-outs, or folded fabric equivalents lay underneath our cutlery as we are seated in a restaurant.

The centuries-old history of the napkin has unfurled from a basic tool to an ornamental accessory. As with most tableware we now take for granted, at some point napkins became a symbol of status –– a medium to be contorted into sculpture, a mark of the host’s wealth, preparation and thoughtfulness towards the meal.

Before table manners, there was bread

The first known use of the word “napkin” dates from the 14th century, although materials of some sort to wipe the hands and mouths of diners, were in use far earlier.1 In Ancient Greece, where food was eaten primarily using the fingers, Spartans apparently used a soft bread dough called ‘apomagdalie’ to wipe their hands, for lack of a better tool.2 This is described by German archaeologist Hugo Blümner in his 19th century work, The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks:

“Table cloths and napkins were unknown; the place of the latter was taken by soft dough, on which the fingers were rubbed. At large banquets, sometimes towels and water for washing the hands were handed round between the courses…The practice of using the fingers for eating made this indispensable.”3

- 1. ‘Napkin’, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2023

2. Liddell and Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon,1889.

3. Hugo Blümner, The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895.

Many sources state that cloth napkins began to be used by European nobility after the introduction of the tablecloth to dining tables. In A Guide to Napkin Folding (1980), James Ginders writes, “it was common practice for the diners to wipe their greasy hands upon their clothes…This being so, it was not long before they perceived that this highly decorated cloth covering the table…could save a great deal of wear and tear on their own linen.” With vast difference to our present day table manners, the tablecloth became a multi-use object, which could be tucked into the collar to catch food, as well as used to wipe one’s hands after eating, until separate napkins became commonplace.

The starched centrepieces of the Baroque

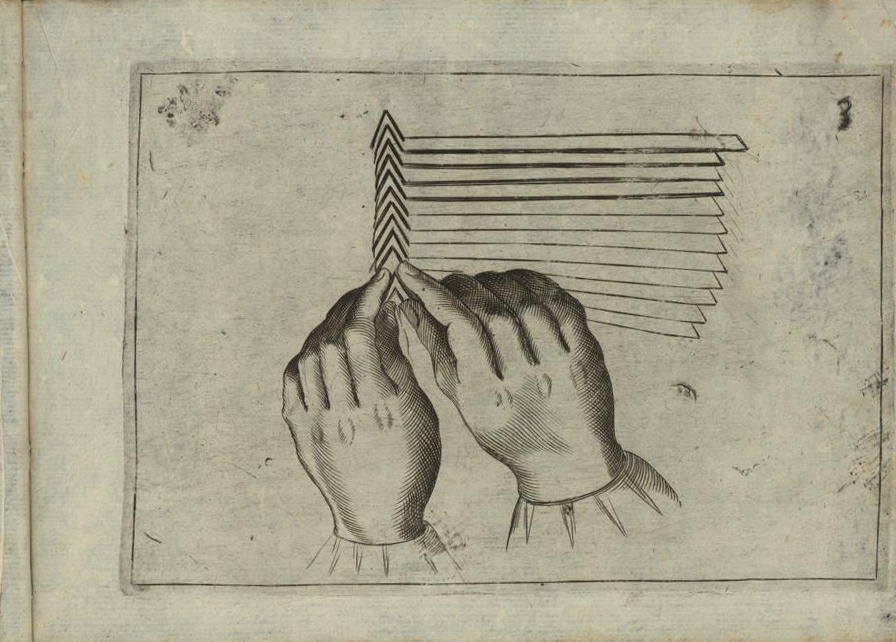

The first substantial documentation of napkin folding appears in Li tre trattati, written by Matthia Giegher in the early 16th century. Born in Germany (as Matthias Jäger), Giegher moved to Padua, Italy and studied the Italian customs of carving and table setting. The publication takes the reader through his studies complete with instructions and rationale, but the true wonder of Geigher’s work lies in the intricate diagrams of napkin folds, including a page of animal sculptures that would appear (to the un-trained napery artist) impossible to recreate.4

Napkin folding was integral to the Baroque dining experience, rather than an optional flourish or afterthought, something that Geigher’s treatise outlines combined with chapters on ‘the table’, seasonal eating, and carving techniques. However, Geigher’s work showcases not only the napkin’s place as a functional ingredient of a well-set table, but its sculptural, artistic qualities, and ability to communicate themes and images to diners. Joan Sallas, a researcher and ‘folding artist’, has described the personalisation of napkin designs:

Joan Sallas for BBC Real Time, 2013“The design of the napkins were different for each person. For example, the fan was normally used for the women, the points (crowns) were used for the men. If the man is more important, the napkin (design) has more points.”

- 4. Matthia Giegher, Li tre trattati, 1629.

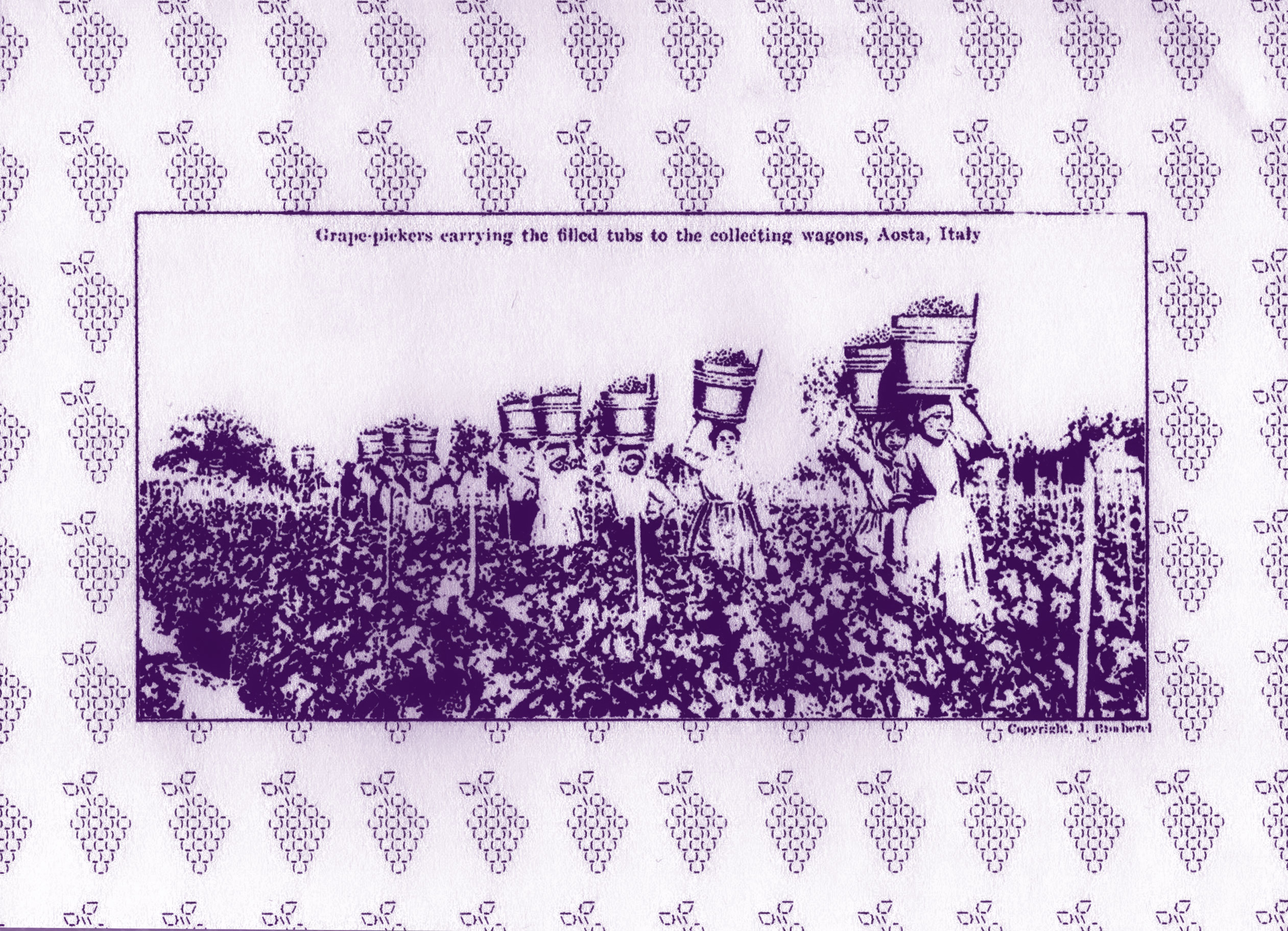

The flamboyant designs in Geigher’s work would have been used in households across Europe, but required lengthy studying and practise to perfect –– it’s no wonder that the tradition didn’t survive. In an article for Catalan textile publication Datatèxtil, Sallas writes that “from the 16th century, centrepieces were made with edible items, such as butter, sugar, pasta, etc., as well as non-edible materials like wood, wax, tragacanth, napkins,” until the need for a more time-efficient centrepiece was satisfied by European porcelain from the 1700s. 5

- 5. Joan Sallas i Campmany, “Mattia Giegher and the first work published on folded centrepieces”, Datatèxtil 40, 2020

From disposable dinnerware to future fare

Table linens remained in use, but the Baroque culture of impressive folded sculptures was replaced by evolving tablescape trends. By the late 1800s, paper napkins were emerging as a convenient solution to traditional napery. Although initially slow to catch-on in America, by the 1940s the nation was sold on the hygienic and time-saving advantages of this disposable alternative –– a precursor to the throwaway culture of single-use servingware. In a segment in the Independent, California, writer and etiquette advisor Emily Post is quoted,

“It is far better form to use paper napkins than linen napkins that were used at breakfast…freshness is of first importance. A mussed napkin is unpleasing, a soiled one is unthinkable.”6

- 6. Independent, California, December 2 1948, p.24.

For the past few decades paper napkins have stood the test of time, used everywhere from the home, to celebrations, restaurants and bars. However, our ‘on-the-go’ eating habits are threatening the napkin’s existence, not to mention traditions of table setting and linens. According to a 2019 Vox feature, only 41% of American households now regularly purchase paper napkins, down from 60% two decades ago.7

It’s likely that not only have changing lifestyles and eating habits affected this drop in popularity, but also environmental concerns –– but we have yet to see the pristinely starched linen napkin make a resurgence. Napkin artists such as Joan Sallas are pioneering this, by investigating the historical traditions of napkin folding, and the who, how and when of a lost culinary culture.

- 7. Michael Waters, “Paper napkins are expensive and environmentally unsound. Now the industry is trying to save itself”, Vox, 2019

In recent years, however, contemporary artists and designers have been creating work that gives a nod towards the nostalgia of cloth-covered table settings. Set designer Jill Burrow, who often makes work with (or with resemblance to) food and tableware, created this al fresco tablescape complete with napkins, placemats and bread for the table – all suspended in mid-air. The artist Laila Gohar’s ‘Bread Bed’ consists of a bedspread stitched together using various flatbreads as textile, considering edible materials as multifunctional (not dissimilar from the apomagdalie of Sparta). Reimagining the routines of table-setting as an art form and/or design process opens up new possibilities for materials, methods, experiences, and relationships. Much like Baroque banqueters, perhaps we ought to compose and consider our dining experiences as a form of communication, speaking with one another through symbols, a language unstated.

- 1. ‘Napkin’, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2023

2. Liddell and Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon,1889.

3. Hugo Blümner, The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895.

- 4. Matthia Giegher, Li tre trattati, 1629.

- 5. Joan Sallas i Campmany, “Mattia Giegher and the first work published on folded centrepieces”, Datatèxtil 40, 2020

- 6. Independent, California, December 2 1948, p.24.

- 7. Michael Waters, “Paper napkins are expensive and environmentally unsound. Now the industry is trying to save itself”, Vox, 2019