Whether you like it or not, jelly has an extensive and diverse history. Whether sweet or surprisingly savory, instant or incredibly time-consuming, it has remained a constant on banquet tables or in the humble kitchen cupboard. Towers of colorful, flavored gelatin have entertained consumers young and old for over a century, and the confection’s resurgence as creative food medium in recent years has only increased this intrigue.

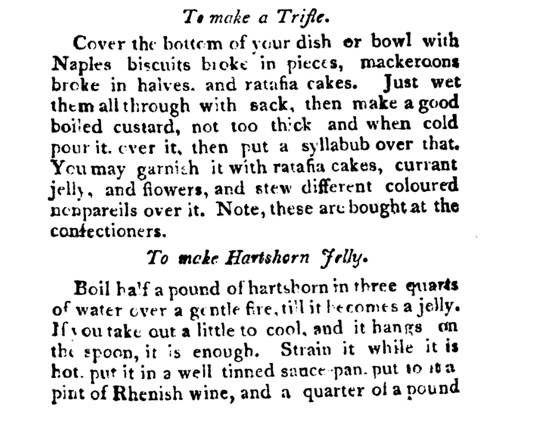

Long before we were turning Jell-O out of tupperware molds, jelly was used to suspend and preserve meat, first appearing in English recipes around the 14th century. In fact, jelly wasn’t even considered a dessert until much later, in books such as The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse (1751) which mentions jelly as an ingredient in a trifle. So how did we transform what could be largely considered an unappealing meat byproduct, into a much-loved family dessert?

FROM A TAXING TASK, TO INSTANT AMBROSIA

One of the earliest instances of jelly in English medieval texts can be found in The Forme of Cury (c.1390), which includes a recipe for ‘gelee of fysche’ (fish jelly) and the appetizingly named ‘gelee of flesche’ (meat jelly). Although these dishes may not sound like a treat for the senses, The Forme of Cury — one of the oldest surviving English cookbooks — was written by the cooks of Richard II of England, a documentation of the lavish banquets created for the king.

At this time, jelly was for the wealthy — households needed to have access to large quantities of meat, as well as enough staff and time for the arduous process of creating gelatin. But by the 19th century, scientific advances had shaped a more informed approach to nutrition, and cooks had begun to reassess gelatin as an inexpensive source of protein. In Defining Culinary Authority: The Transformation of Cooking in France 1650-1830, Jennifer Davis states that culinary research during the Napoleonic wars included, “new methods of stock preparation to sustain the nation’s poor, and new methods of extracting gelatin from bones to improve hospital and military diets at little added expense.”

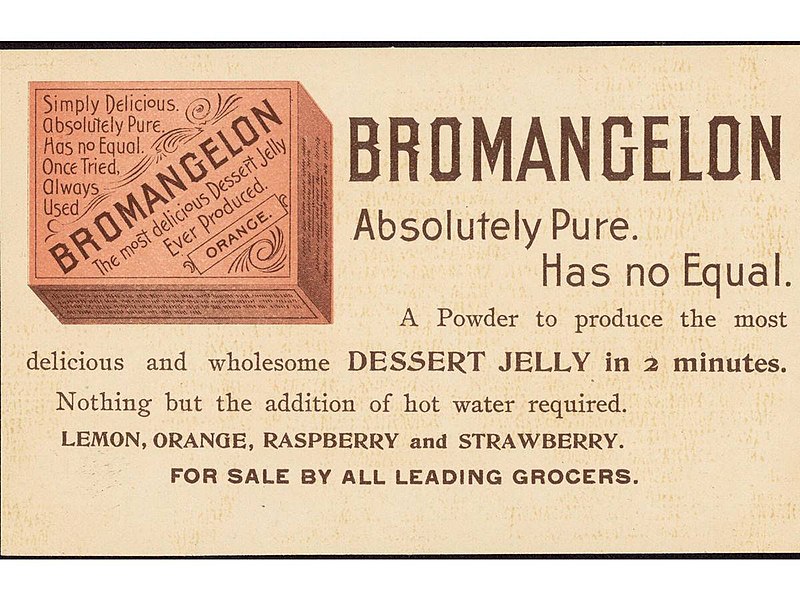

But gelatin alone is colorless, odorless and most significantly, tasteless unless additional ingredients are added. By the late 19th century, inventors were beginning to experiment with flavor in order to make gelatin more appealing to the masses. One of the first instant gelatin desserts, Bromangelon, was developed by Leo Hirschfeld, an Austrian living in the United States, who later went on to invent the Tootsie Roll. The launch of Bromangelon, powdered gelatin sweetened with flavorings, meant that impressive jelly desserts were now accessible to home cooks everywhere, without the tiresome and unappealing task of making gelatin themselves from raw animal materials. Initially available in four flavors – lemon, orange, raspberry and strawberry – it wasn’t long before books and magazines were advertising inventive concoctions incorporating the novelty ingredient. A recipe in Good Housekeeping magazine in 1900 used Bromangelon as the star ingredient for a Shredded Wheat Biscuit Jellied Apple Sandwich, while Woman’s Favorite Cook Book (1902) by Annie R. Gregory featured several Bromangelon-centered recipes, including a “Dessert Surpassing Ice Cream”. A cookbook published by the Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society of New York Orphan Asylum in 1909 presents a recipe for a celery and walnut salad suspended in lemon Bromangelon.

Bromangelon’s mass marketing promoted its “purity” and simplicity, a household staple for creating all manner of impressive centerpieces, with just a touch of creativity and the addition of a few strange ingredients. The brand’s advertisements may have claimed that Bromangelon “has no equal”, but it was soon driven to obsoletion by the arrival of Jell-O just a few years later, developed by Pearle and May Wait.

A CONVENIENT CULINARY SENSATION

Jell-O as a product bore great similarity to Bromangelon, but the difference came down to its advertising. Family-centered messaging sold the product to housewives looking to satisfy their children’s tastes “without eggs, cream or fats”, promoting the endless possibilities for such a convenient product.

Jell-O introduced more flavors and colours to appeal to home cooks looking to impress their family or guests, and released advertising campaigns illustrated by Norman Rockwell — often featuring a child enjoying Jell-O, or a mother serving Jell-O to awaiting children.

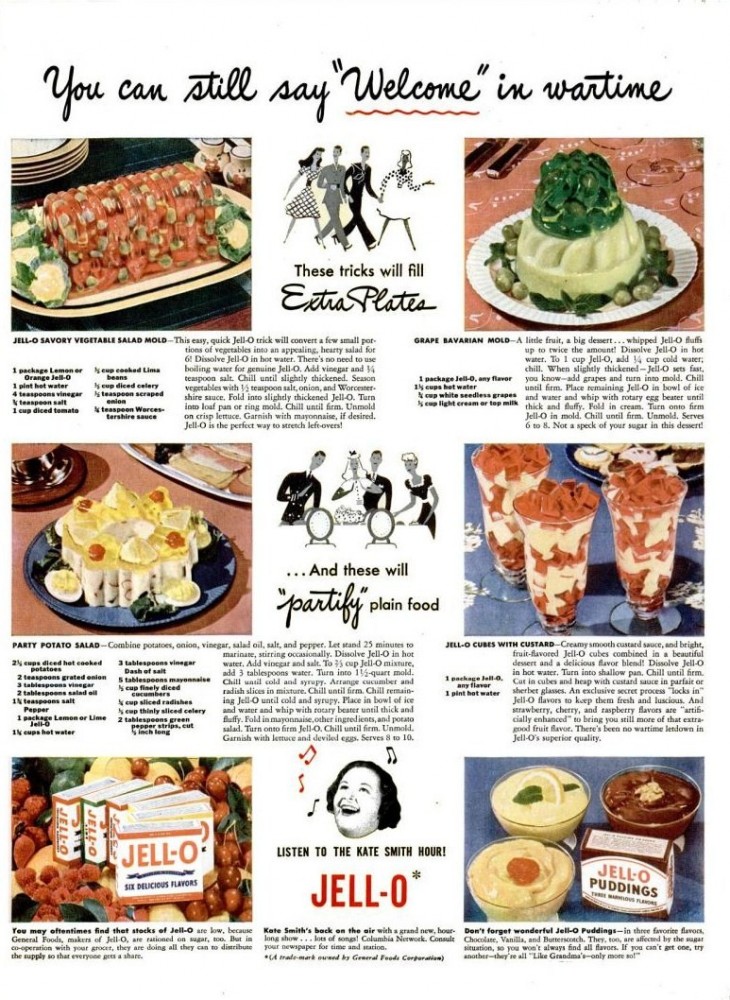

During the Great Depression and World War II, “America’s most famous dessert” changed tack, advertising Jell-O’s ability to liven up even the dullest of dinners. Promotional material suggested jelly was a way to create impressive meals even during rationing, or as a method to preserve or add bulk to leftovers. Molded jelly centerpieces, reminiscent of Victorian banquets at first glance, were filled with chopped vegetables or meat, and topped with mayonnaise. Jell-O even later introduced savory flavors to make these “Jell-O salads” more palatable, including mixed vegetable, celery and tomato — although these were short-lived.

DOES JELL-O HAVE A FUTURE?

Beyond the 1970s, we seemed to lose appetite for the spectacle of Jell-O salads and other artistic, gelatinous creations. Although Jell-O continued to market its products as a convenience food capable of great things, a post-war America no longer wanted to associate its diet with memories of frugality and leftover-stretching.

In spite of this decrease in popularity, Jell-O continues to retain its status as a household dessert throughout America, although with notably less spectacle than previous decades. However, a recent revival of interest in the nostalgia of jellied salads and molded centerpieces suggests that our fascination with the ornamental, bizarre qualities of these dishes is far from over.

Could there be a future for jelly in our ever-evolving food systems? Could jelly’s historical significance help us to imagine creative solutions to the world’s future obstacles?

Food design innovations in recent years have increasingly imagined jelly as a vessel to encourage consumers to think about the eating experience, and new possibilities for the historical dish. London-based creative studio Bompas & Parr first made their mark in the world of contemporary food design as an artisanal jelly company. Their project Jelly Parlour of Wonders incorporated 3D scanning and replicating historic jelly mold designs. Alongside their now diverse portfolio of sensory food and drink projects, Bompas & Parr have launched Benham & Froud, reviving the centuries-old British company “that made the ‘Rolls Royce of jelly moulds’”.

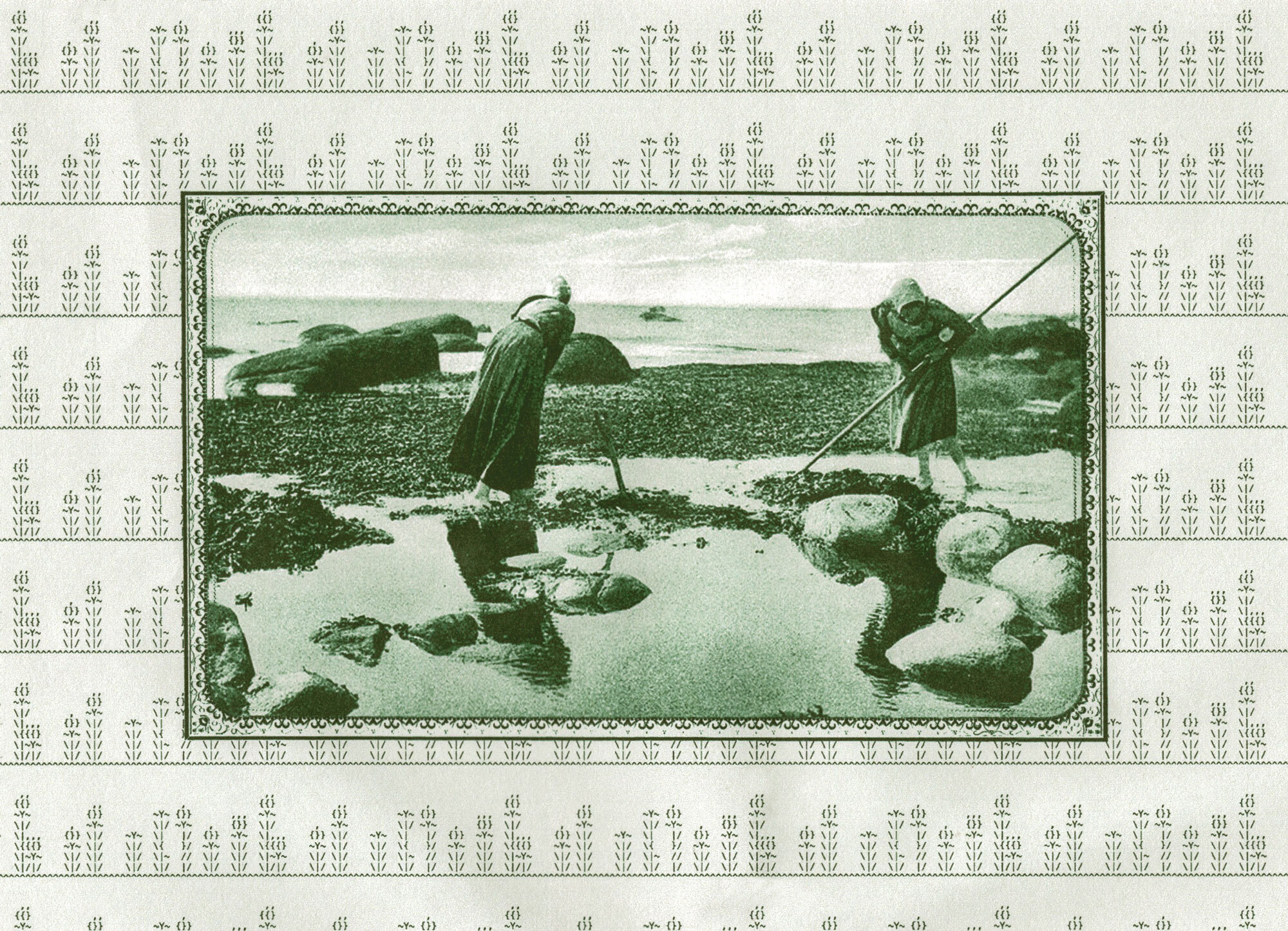

Meanwhile, designer Malu Lücking’s Landless Food proposes a “regeneration of humanity’s food system” using microalgae grown on agar jelly (a vegetarian alternative to gelatin, extracted from seaweed). Lücking manipulated the tastes of the microalgae to reflect seafood flavors that may soon be only memories. Rebecca Cairns, for CNN, remarks that “when consumed with the jelly [the microalgae] functions like a stock cube” — mirroring the days of gelatin as a culinary companion for meat and fish.

Gelatin is essentially a byproduct of animal food industries, and as many concerns around our current food production look to tackle waste, how can we develop creative uses for the materials that are left behind? For centuries, gelatin has been used as a method of preserving food, either to keep meat and fish fresh, or vegetables crisp. Perhaps considering the resourcefulness of home cooks in times of limited resources opens possibilities for the future of preservation, and the innovation required to build a future, perhaps not for Jell-O, but for an ambitious and resilient food system.