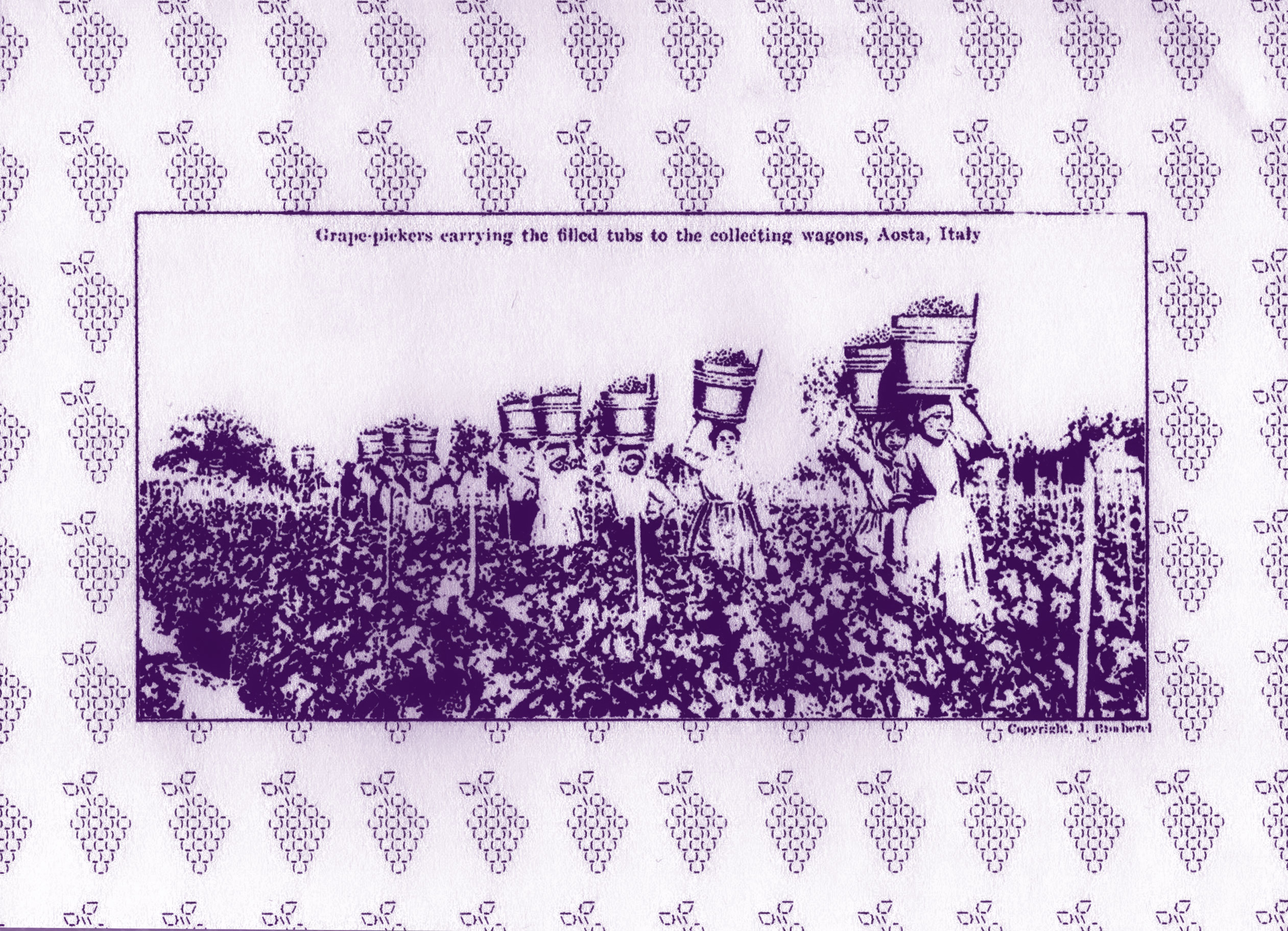

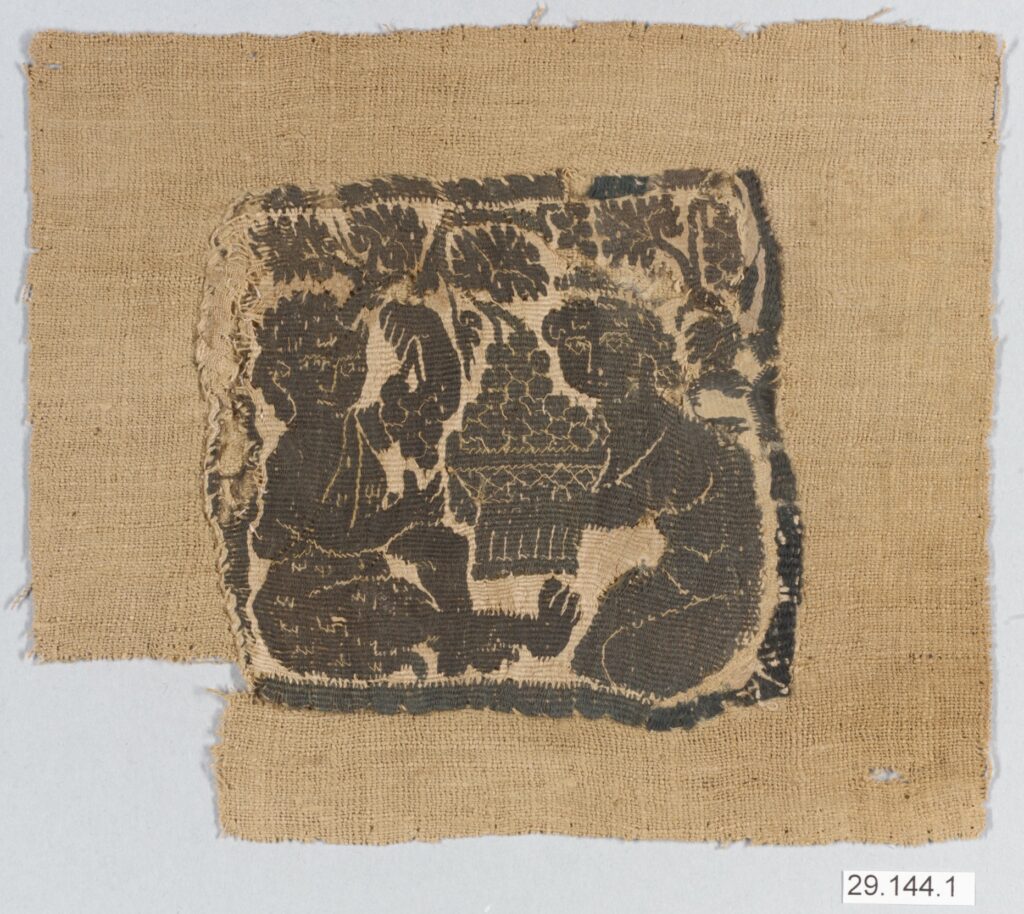

Once a food reserved for the wealthy and elite, grapes have become a popular everyday snack as a result of centuries of cultivation. Documented throughout history across Egyptian hieroglyphs and Renaissance still-life arrangements, the clusters of berries were used to represent abundance and fertility.

Grape production worldwide has since increased by over 65% in the last 50 years (using data from FAOSTAT). The modern grape varieties we know now likely descended from domestication which took place in Asia1. Excavations at Astana Cemetery in Xinjiang, China, have revealed well-preserved remains of food buried in the tombs, including grapes – dating back to the 8th century. Archeological evidence suggests that humans began growing grapes as early as 6500 BC, meaning they are likely one of the earliest cultivated crops.

That these berries were considered valuable enough to be taken into the afterlife, is no surprise when we consider the significance of their symbolism throughout ancient civilizations, religion and art. Grapes have often been displayed as tokens of abundance, fertility and celebration, from the ancient Greek god of “fruitfulness” (and wine) Dionysus, to Christian symbolism in Flemish paintings.

- 1. “The genomes of 204 Vitis vinifera accessions reveal the origin of European wine grapes”, Magris, G., Jurman, I., Fornasiero, A. et al., Nature Communications, December 21 2021.

- 2. “Grapes: A Brief History”, David Trinklein, Integrated Pest Management, University of Missouri, August 7 2013.

Agricultural heritage at risk

Although the earliest domestication of grapes may have taken place in Asia, it wasn’t long before viticulture had traveled across continents, from Europe to the Americas. While there are a few names we might recognise, many ancient varieties are now endangered as farmers continue to favor popular wine-making grapes or hardier varieties. The Ark of Taste, a catalog of at-risk species that is maintained by the Slow Food Movement, lists countless grape varieties that are “in danger” of being lost due to environmental, economic, social and political shifts.

Bacò

The small, black Bacò grape of Veneto, Italy dates back to 1902 when it was bred from a European and American grape by François Baco. It was harvested for its bright, acidic wine, but was later banned for its high tannin percentage –– “the wine had to be drunk within 4 months…otherwise it would become vinegar” (Ark of Taste). Currently, a few people still grow Bacò grapes to make wine for themselves as it cannot be sold.

Cèsar

The Cèsar grape dates back to the second century BC, where the variety was planted in Yonne, France, by the Romans. Notoriously difficult to mature, only four acres of this grape are grown today, as the variety has been ignored due to the popularity of pinot noir (the grape from which the Cèsar was bred from).

Bondola

Almost completely unknown outside of Tessin, Switzerland, the indigenous red grape, Bondola made up 50% of locally-grown grapes in the area in the 1950s. Now, the variety has almost disappeared due to a widespread preference for Merlot. Remaining local growers still protect this variety and value its agricultural importance.

Pulëz

The Pulëz grape has been grown by Albanian farmers for centuries, to produce highly alcoholic white wines. Raki (a distilled grape drink) celebrations still occur in these rural areas, while local wineries hold celebrations of pulëz wine in September. Pulëz grapes have also been used to dye bread with their rich juices. Despite a revival of interest in local produce, young people moving away from rural communities threatens the future of this cultivar.

These grape varieties are not only important for the biodiversity of farming and food production, these breeds hold great significance for the communities that have grown, harvested and shared them.

Designing fruit for the future

In the introduction of The Way We Eat Now, food writer Bee Wilson dissects the act of eating a grape:

“Grapes have become a piece of engineering designed to please modern eaters…it is only in the past two decades that seedless has become the norm, to spare us the dreadful inconvenience of pips.

…the mainstream ones in the supermarket such as Thompson Seedless and Crimson Flame are always sweet…On biting into a grape, the ancients did not know if it would be ripe or sour…These days, the sweetness of grapes is a sure bet, because in common with other modern fruits such as red grapefruit and Pink Lady apples, our grapes have been carefully bred and ripened to appeal to consumers reared on sugary foods.”

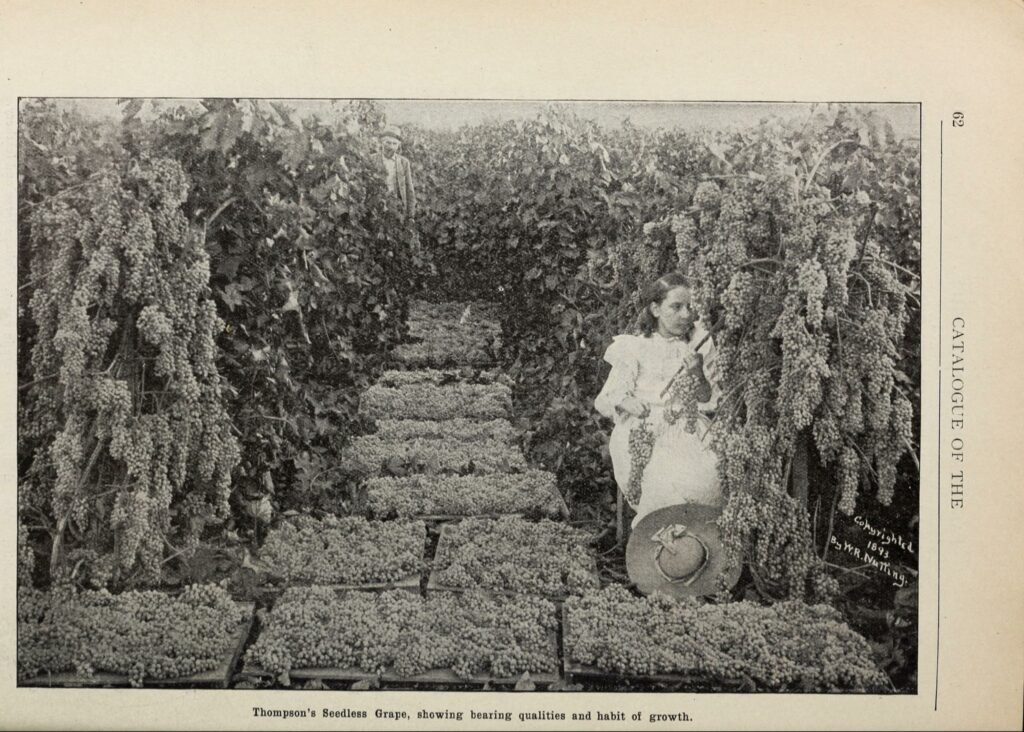

Thompson Seedless was the first widely commercialized seedless grape variety, brought to California by William Thompson in 1878 –– however, it was later discovered to be the same as the Sultanina, found in Asia Minor, not a new discovery by Thompson. The variety’s popularity grew worldwide due to its conveniently seedless flesh, large fruits and crisp skin.

The cultivation of seedless varieties in the early 20th century enabled the grape to be redesigned as an accessible fruit for everyday consumption, rather than an item reserved for luxury and plagued with the inconvenience of seeds. Enter, the table grape –– large, bountiful clusters of grapes which can be easily picked up and snacked upon every day. If the Ancient Greeks perceived grapes as a symbol of abundance, the modern Western world was determined to make this prosperity achievable for all growers and consumers.

The preservation of pét-nat

Like most produce we consume today, we are given a choice of a few almost indistinguishable varieties of grape (that are high-yielding, less likely to become diseased, and engineered to suit the mainstream consumer’s taste) while heritage breeds and gustatory traditions are at risk of disappearing from the table.

However, the turn towards natural wines in the past couple of decades prioritizes, as the name suggests, “natural” flavors and processes; rejecting agricultural chemicals, temperature control, or filtration. Natural wine is not a new phenomenon, but rather a return to traditional practices, centuries old, that reconnect us with the rural environments behind the products we consume.

In recent years we’ve seen natural and organic wineries revive ancient processes such as pét-nat –– or pétillant naturel, meaning “naturally sparkling” –– or rancio wines, which are aged in partially-filled barrels to increase oxidation. The move to use grape varieties that are themselves at risk of extinction, has been slightly slower to take off, however not unnoticed. Santa Rosa-based winery The Folk Machine sell their Valdiguie worldwide, a grape that according to the Ark of Taste was “misidentified for decades” as a Gamay by California vineyards. The grape is now known interchangeably as a Napa Gamay or Valdiguie. London-based natural wine supplier Top Cuvée sell a bottle of the curious Spanish Txakoli, a local wine used to make the complex Txakoli wine vinegar of the Basque country. As the Ark of Taste documents, “in this agricultural centre, not even a litre of txakoli was ever wasted; when it was no longer good to be drunk as wine, it would be used for the preparation of pickles and preserves.”

Writing for The New Yorker in 2019, Rachel Monroe unpicks the “mainstreaming” of natural wines, stating that it “fit in with the urban appetite for movements that evoked a slower, more earthbound past”. Organic and biodynamic farming practices further appeal to the climate-conscious, along with wines that taste “wild” or “funky”, a flavor that mirrors the land and conditions in which the grapes were grown, harvested and processed. Is this a connection we have lost with commercial wines and mass-produced table grapes?

There are hundreds of cultivars of grape that are in danger of no longer being tasted –– or no longer being grown at all –– due to the names that fill supermarket shelves: Cabernet, Sauvignon or the popular Thompson Seedless. Is the history of one of the oldest cultivated foods being washed away by our hunger for convenience and the pressures of commercial farming? Perhaps we can begin to appreciate the stories and paths behind the grapes that have made it to our tables (or glasses) and the work that has gone into growing them. There might something to be learned from the cult following of low-intervention wine, if we just begin to take a closer look at the label.