Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

In response to the ongoing farmers protests in India and its spread to Punjab’s neighbouring state of Haryana, the Indian government has pledged to increase the purchase price of wheat by just 2%2 . This has been met with outrage from agitated farmers who have been fighting for control in the trade of their own produce, for example a legally-enforced minimum support price (MSP), since 2020. This battle for food sovereignty from one of the world’s largest producers of commodities such as grains, pulses and livestock, reminds us of the stark reality of our unsustainable food systems.

- 1. You can find out more on the Green Revolution, in Degrowth in Demand a conversation between activist, Jamie Tyberg, and researcher and breadmaker, Lexie Smyth.

- 2. World Grain

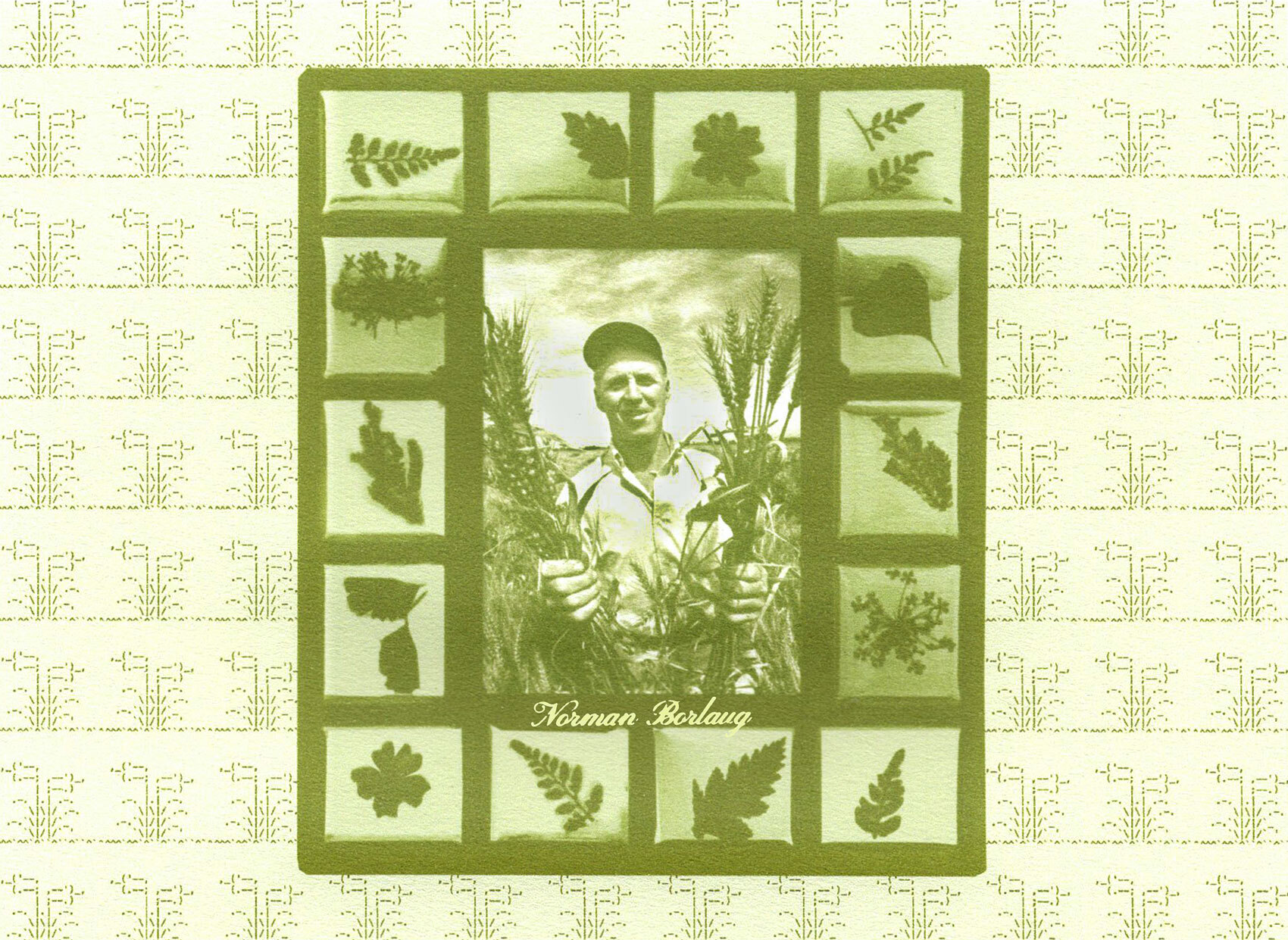

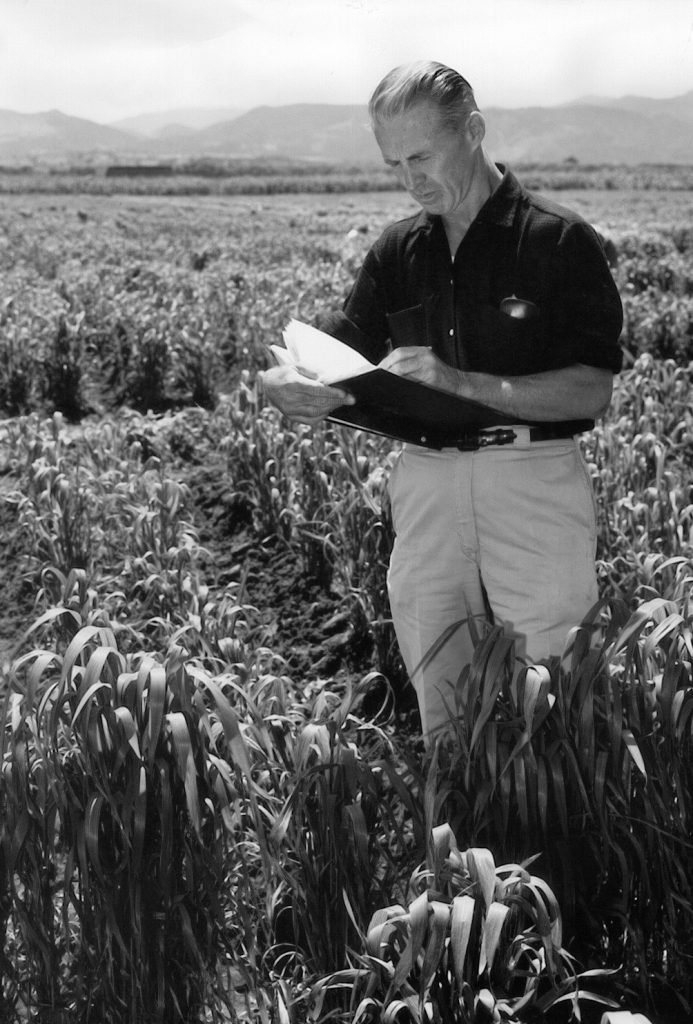

Improving the livelihoods and conditions of those who produce our food has been a cause we’ve seen many fight for throughout history, from George Washington Carver’s educational programmes for black farmers, to UFW’s tireless activism and strikes. Norman Borlaug, a plant pathologist and the “architect” of the Green Revolution, has also been credited with saving the lives of millions with his agricultural research which aimed to cure hunger across the world. But was his revolution an example of philanthropic innovation, or ecological and cultural ignorance?

Seeds of Change

Growing up on an Iowa farm, Borlaug experienced the struggles of food shortages and the intensive labour required to produce enough food to feed one’s own family first hand.

The arrival of the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, and the destruction its drought and dust storms wreaked on not only farmland and crops but also the livelihoods of those working the land, only further confirmed to Borlaug the vulnerability of American agricultural practices. He decided that high-yielding crops grown on intensively farmed land held the answer to avoid such tragedies. To this logic, another Dust Bowl could be prevented—crops that produced more food would feed more people and consistently farming the same land would reduce the need to plough more.

A Miracle Cure for Hunger

By the 1940s, Norman Borlaug was working at the International Centre for Maize and Wheat Improvement (CIMMYT) in Mexico, where he worked tirelessly to cross-breed wheat varieties, selectively growing strains that were disease-resistant and would produce higher yields. Some have referred to Borlaug’s work here as an early version of GMO crops3. By 1954 Borlaug’s team was marketing their “Miracle Wheat”, a high-yielding dwarf wheat —however, the strain required vast amounts of fertilizer to reach its full potential, and therefore far more water than standard varieties. Although Borlaug did campaign for the use of organic fertilizers, the quantity needed was impractical, and this resulted in the widespread use of inorganic chemical fertilizers.

In 1963, Norman Borlaug took his high-yielding wheat to Pakistan and India, countries where food shortages and starvation were increasing due to wide-spread famine. By the 1970s, both countries were self-sufficient in terms of wheat production. The program spread further into countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Egypt, as Borlaug attempted to solve world hunger with this modified crop.

Borlaug’s work was rooted in good intentions, and did increase wheat production—by 1956 Mexico had doubled its production, and by 1963 production was six times that of 1944 when his work had begun at CIMMYT. However, looking back at the story of the Green Revolution now, it isn’t hard to see the environmental and social consequences that would arise from these practices.

In a lecture delivered in 2014 at Arizona State University’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, physicist and philosopher Vandana Shiva decodes the etymology of the Green Revolution’s name:

“The colour green did not come from the philosophy green. There was no philosophy green in the ‘60s. The green movement grew much later as a sustainability movement. Green was just a colour different from red. And red is what you didn’t want.”

Miracle or Mythology

By the ‘80s, environmentalists began to apply pressure to Borlaug’s program due to the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers and increased irrigation needed for the so-called Miracle Seeds to succeed and feed global populations. Notable criticism has come from Shiva, who has examined the impact of the Green Revolution on India’s farming culture.

In an interview with Global Oneness Project, Shiva illustrates the “mythology” of the Revolution:

“It is a mythology, it’s not a science. They talk of miracle seeds, they talk of feeding India, all they did was put more water and more land under rice and wheat, then you’re going to get more rice and wheat.”

Her research and writing argues that the secret of the Green Revolution was simply the increased irrigation and fertilization, which produced the “same amount of food as you would in ecological farming”. The construction of dams in northern India to accommodate the increased need for irrigation drowned entire towns under water — for example the old town of Tehri which was submerged during the construction of the Tehri dam, displacing inhabitants and creating cause for environmental concern.

The water and chemical-intensive methods that Borlaug’s program encouraged went against historical agricultural practices. “When you are careless with water, farming becomes careless,” Shiva states on the harm done by the Green Revolution to our food systems.

In Food Resources: Conventional and Novel (1976) British biochemist N.W. Pirie highlights an unsettling feature of the Revolution. “It could indeed be regarded as ‘scientific colonialism’,” he writes, commenting on the tendency of scientists to attempt to continue their work in less developed countries, and a “lack of official appreciation of agricultural and other biological potentialities.” Vandana Shiva only strengthens this point, telling us that by the 1980s Indian farmers found themselves in debt, having to increase the application of pesticides and fertilizers due to pests and depleted soil health, while farms were bought out by large corporations. Historically grown crops such as millet, which required far less water to produce food, had been displaced in favour of Borlaug’s ‘miracle wheat’.

Not only were farmers’ livelihoods becoming increasingly vulnerable, but as we now know, increased chemical use is likely to pollute nearby water supply. A 2009 Greenpeace investigation of 50 villages in the Muktsar, Bathinda and Ludhiana districts of Punjab revealed that 20% of the wells sampled had nitrate levels above the WHO limit for drinking water –– a pollutant most likely caused by the overuse of nitrogen fertilizers, a product of fossil fuels4.

- 4. “Chemical fertilizers in our water – An analysis of nitrates in the groundwater in Punjab”, Greenpeace India Society, November 2009

Choosing a Future for Farming

This essay offers just an introduction to the complexities of the agricultural revolution that Borlaug designed, which has been backed by large American organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. While Norman may have set out in the 1940s with all the right intentions — to fight world hunger, breed crops that could withstand disease and produce more food for those most in need —we are still living in a world in which farmers cannot earn a living wage, and hundreds of millions go hungry.

Rob Rapley, who wrote and directed the 2020 documentary The Man Who Tried to Feed the World, believes we can learn from the consequences of Borlaug’s project:

“Those costs have been as important as the problem that it solved, and we now find ourselves, 50 years later, wedded to a system that’s contributing to climate change and causing much human misery.”

Borlaug changed the agricultural industry by bringing intensive farming and higher production to less developed countries. However, this didn’t solve hunger or poverty, and it certainly didn’t support the natural environment. So how can we ethically produce enough food to feed the world, while also benefiting the environment and counteracting climate change? Is it even possible?

The United Kingdom’s recently published National Food Strategy – commissioned by the government and written by Henry Dimbleby – sets out a plan for a complete overhaul of food production and consumption, including how we farm crops and livestock. It suggests a “three-compartment” approach, wherein an area should exhibit a combination of high-yield farmland and regenerative, low-yield farmland to support the environment as well as ensuring enough food can be produced. The third “compartment” is left to grow wild, conserving biodiversity and sequestering carbon.

Still a novel idea, we have yet to discover how this could be implemented across the world. Does it have the capacity to feed everyone, and allow farmers control of their land and income? Can we abandon the intensive agricultural practices that are resulting in poor soil, plant disease and pollution? We cannot possibly make these decisions without considering the effect of any changes on independent farmers, and their own lifelong methods and livelihoods. In her speech at the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, Vandana Shiva recalled a declaration of the Sarbat Khalsa in Punjab:

“When you can’t choose what you grow, when you can’t decide the methods of production, when you don’t determine the price of what you produce, when your own rivers…water can’t be released through your decision…then we are living under slavery.”