Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

Many people like to think we live in a world where our food is easy to access and nutritious. And while that may be true for privileged individuals, a quick survey of recent news ranging from the outrage over the quality of UK free school meal parcels delivered over lockdown, the statistics on the sharp rise of food insecurity in the United States during the pandemic, or the ongoing Indian farmers’ protests, makes it blindingly obvious that this is not the case. An overall lack of education and disconnection from our food and its origins—particularly by those making policy—can make transforming systems into the sustainable ideal feel like a lost cause. Where should the education start? How do we change the food system from the very roots? A lesser-known researcher of the reformation of food production and consumption is George Washington Carver. Primarily known for his advocation of peanut crops, Carver was an agricultural scientist who went from a childhood of slavery to a career in academia and creative research. He dedicated his life to delivering food and agricultural education to thousands of students, farmhands and families, and was celebrated for his “Deweyan sense of process in science” (Vincent McHugh, 1943).

The Plant Doctor

George Washington Carver was born into slavery around 1864, spending the first years of his life enslaved on a plantation in Missouri. According to Iowa State University’s biography of Carver, he developed an interest in plants and the natural world from an early age, becoming known as the “plant doctor” around the neighborhood1.

By 1890, his continual thirst for knowledge led him to become the first African American to attend Simpson College in Iowa, where he studied painting. By 1896, Carver had gained a Masters degree in agriculture from Iowa State Agriculture College, swayed by his horticultural interests into a more scientific path of study. He was invited by Booker T. Washington, another African American educator and founder of what is now Tuskegee University, to join him in Alabama, as head of the new agricultural department2.

Washington had won federal funding for an agricultural experimental station (AES) to further scientific research in food production—which became the first all-black experimental station in the United States. Agricultural experimental stations were often part of “land-grant” universities such as Tuskegee; these were colleges granted land by the Morrill Act to further education in agriculture, science or engineering as a response to the industrial revolution. Experimental stations were there to conduct research and practical experiments to bring new ideas and solutions to agribusiness, and therefore the economy of the United States. This research included ways to improve the standard of rural life and the wellbeing of both farmers and consumers. Institutions led by black academics received notably less support than previous grants (which were awarded to solely white colleges), but Washington and Carver were two educators determined to conduct research with great impact, albeit with far less resources.

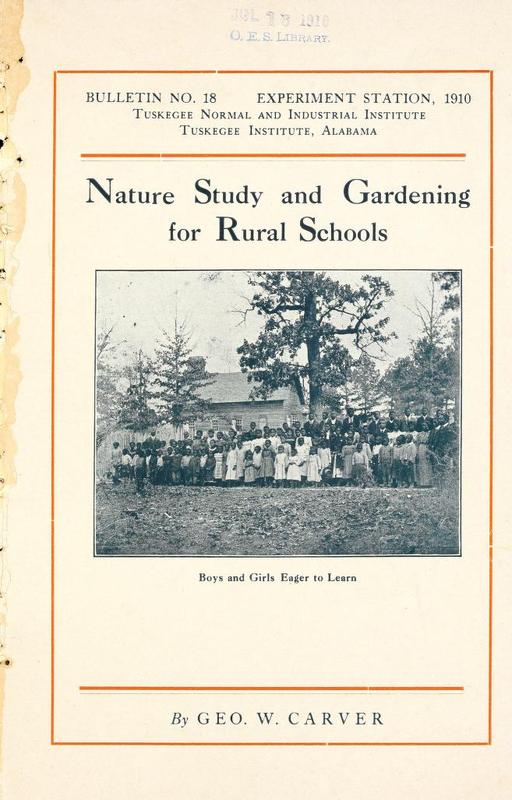

The 10-acre plot that housed the Tuskegee Agriculture Experimental Station was directed by Carver, who dedicated his work to improving the lives of both black and white southern farmers, many of whom were in a perpetual state of poverty and despair, forced into peonage (paying off financial debt with more labor). A key element of Carver’s ethos was repackaging and distributing the findings of his research to the farmers that needed it. Determined for Tuskegee to gain the respect of the agricultural community and the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), he aimed to issue bulletins once a quarter, free of charge. Unfortunately, this didn’t become reality, averaging only one to two bulletins each year. The neighboring research station at Auburn outproduced Carver’s efforts, but funding and staffing were on their side. Linda O. Hines, writing for Agricultural History in 1979, notes that by 1905 Auburn had 13 staff members, while Carver personally produced 29 of his bulletins himself.

(1910). George Washington Carver. Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute Experiment Station. Bulletin Number 18.

Crop Rotation, Cotton and Cowpeas

In The Need of Scientific Agriculture in the South, published in 1902, Carver wrote of the dismal conditions faced by southern farmers:

“The average Southern farm has but little more to offer than about one-third of a cotton crop, selling at 2 and 3 cents per pound less than it cost to produce it, together with the proverbial mule, implements more or less primitive, and frequently a vast territory of barren and furrowed hillsides and wasted valleys. Another mortgage may have been added as an unpleasant reminder of the year’s hard labor.” — G. W. Carver, The Need of Scientific Agriculture in the South, Tuskegee Institute, Farmer’s Leaflet 7 (Tuskegee, 1902).

Farms in the South prioritised growing cotton—but this reliance on cotton and the practice of ‘monocropping’ (growing the same crop on the same land, year after year) was leading to a depletion of nutrients in the soil,damaging the output of the farms—and the farmworkers’ livelihoods. From 1902 to 1905, Carver started to dedicate his research to finding alternatives to growing cotton. He carried out crop rotation experiments—a method championed by modern farmers practices—and published his findings in Bulletin 6, “How to Build Up Worn Out Soils”. Beyond rotating crops to reintroduce nutrients to the ground, Carver also promoted organic fertilizers—using natural materials to increase productivity—now commonplace in organic and biodynamic farming methods.

Carver’s experiments, although diverse across the agricultural field, eventually landed on several plants that he proposed could absolve small farms of their debts, promote the health and nutrition of both farmers and consumers, and free farms from the repetitive strain of cotton cropping. These plants included cowpeas, sweet potatoes, and peanuts. In fact, Bulletin 5 (1903) was simply titled Cow Peas, and featured 25 recipes providing innovative uses of the underappreciated legume. These included Boiled Peas with Bacon, Griddle Cakes made with pea meal, Pea Coffee, and Creamed Peas—with “(Delicious)” added next to the recipe title. His studies of legumes found that they produced nitrogen, which if plowed into the ground could fertilize soil that had been depleted from monocropping cotton plants.

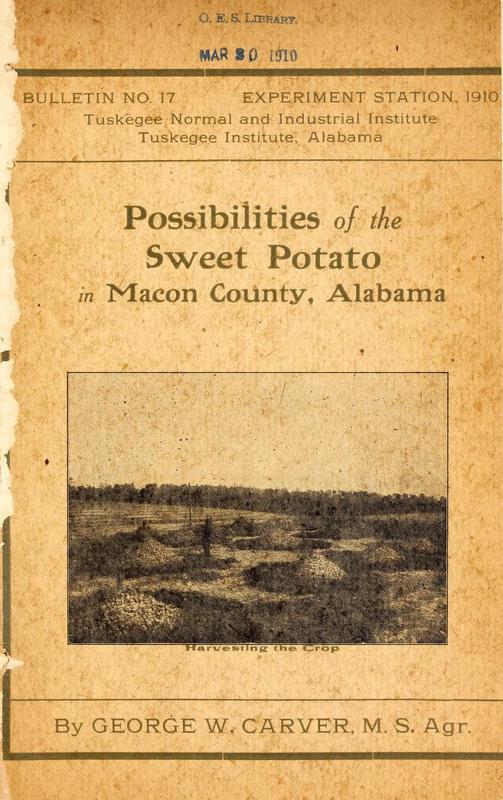

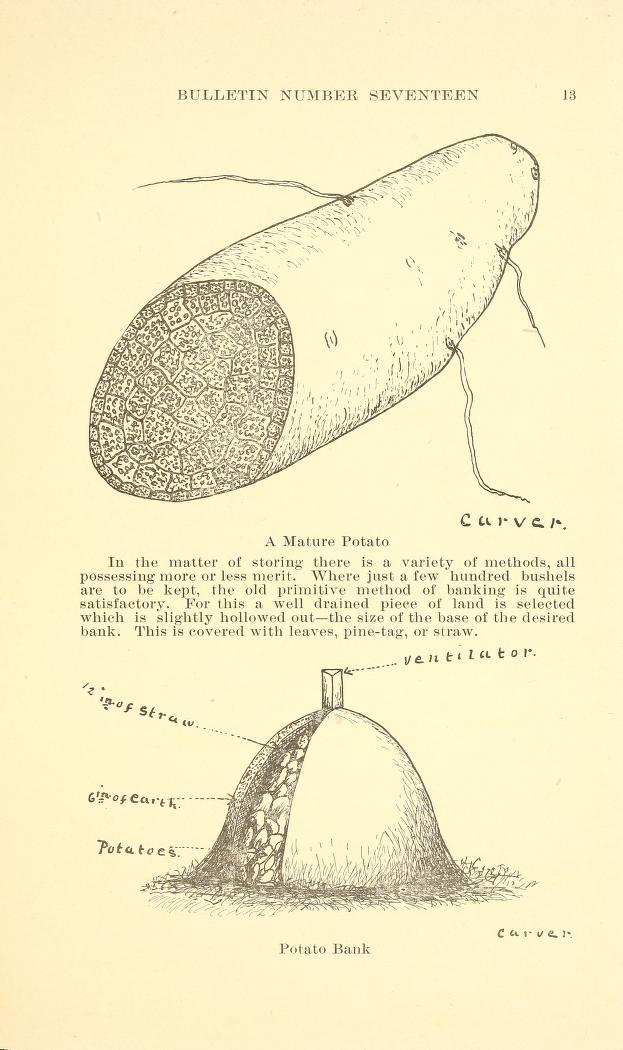

While we may note that Carver wasn’t necessarily making radical discoveries with this work—early forms of crop rotation are thought to have been practiced as early as 6000BC—it was his dedication to making these findings accessible and exciting for southern farmers that set him apart. A flick through any of his 30 or so bulletins published while at Tuskegee will show clear illustrations and labelled diagrams, simple and nourishing recipes for farmers and their families, and everyday language free of jargon. For example, the below page from Possibilities of the Sweet Potato in Macon County, Alabama (Bulletin 17, 1910), details a cross-section of what a mature potato should look like, and how to build a potato bank for storage.

As well as highlighting cowpeas and sweet potatoes as nourishment for land, man and beast, Carver also grew particularly fixated on the peanut as a valuable source of protein. Bulletin 31, published in 1917 was titled How to Grow the Peanut: And 105 Ways of Preparing it For Human Consumption, celebrating “their almost limitless possibilities”. Within these possibilities were multiple versions of peanut soup, peanut bread, peanut cakes and confections – as well as meat alternatives such as Mock Chicken, made from slices of sweet potato covered in a ground peanut and egg mixture, and fried “to a chicken brown.” The American Peanut Council states that George Washington Carver actually found over 300 uses for the humble peanut, although he is not credited as the inventor of any.

A Future for Radical Education

Carver’s work at Tuskegee continued until his death in 1943, as did his research advocating for peanuts and alternative food crops. He also created a Movable School, which he and his staff drove around to rural areas in Alabama to carry out demonstrations and deliver hands-on learning to those without the resources or even reading ability to learn from his bulletins. For the Journal of Black Studies in 1988, LaVerne Gyant writes that “Washington and Carver made contributions to the field of adult education long before it was a discipline worthy of scholarly enquiry.” With limited resources and little-to-no funds, Carver improvised and used his surrounding environment and knowledge of rural communities to research, experiment and teach – and repackaged these scientific findings into an accessible format for his audience. In fact, his lack of funding is exactly what made his work accessible for the black farmer in the South. Carver’s life’s work is a stark reminder of the relationship between creativity and science, especially when persevering to repair our food systems.

In “Abundance From Old Fields: George Washington Carver – A Study of Genius,” Vincent McHugh writes for The New York Times in 1943 that Carver was “a man endowed with transcendent ability”. The white dominance in agricultural programs ultimately led to a lack of recognition or official patents for his research, but his work displayed a radical approach to education which started in the fields of communities where help was most needed. Carver worked tirelessly for over four decades to inform, educate and inspire not only farmers and growers, but consumers, to develop a deep understanding of their land and food—we still have a lot to learn if we are to be successful in creating affordable, accessible and fair food systems.