On the night that my grandmother died, my sister and I shared a bedroom at my father’s house and chatted late into the night, swapping stories and memories of my yiayia. Just as we were drifting off to sleep, I was startled awake by an alarming thought. She’ll never make us keftedes again, I said out loud to my sister as reality set in. My grandma’s keftedes, crispy, heavily seasoned meatballs, were the stuff of legends and her recipe, a pork and parsley secret, had died along with her. In the 8 years since her death, I have tried multiple times to make them but they’ve never been as good as hers. I remember their exact texture, how finely she would chop the herbs, the smell of onions frying, how her hands, aged with sun spots and covered in jewellery, rolled the mince into little rugby-shaped balls.

When the people we love die, we miss their physical company, but we also miss the way that they did things. How they walked, the way they talked, or how they would always sing the words of a particular song wrong. The food that they made us, however, takes on new dimensions of remembrance because it is attached to a multi-sensory experience. Smell and taste are particularly emotive senses as they pass through the limbic system of the brain which is intrinsically connected to memory and emotion. It is for this reason that food is so effective at transporting us back to a specific memory.

Ghostly Archive, a TikTok page documenting the tradition of gravestone recipes, taps into food’s power to evoke memory, all while exploring our relationships to death. In a recent interview, Rosie Grant who created the project tells me, “Recipes can be connected to a specific person in a really tangible way.” Cooking a recipe that’s been passed down is a way to relive that special connection, “You’re smelling the smells and tasting what they tasted. When I think about my own family, both my grandmas had very specific dishes that they made, and when I have that dish I will immediately think about my 8th birthday or whatever the food memory is.”

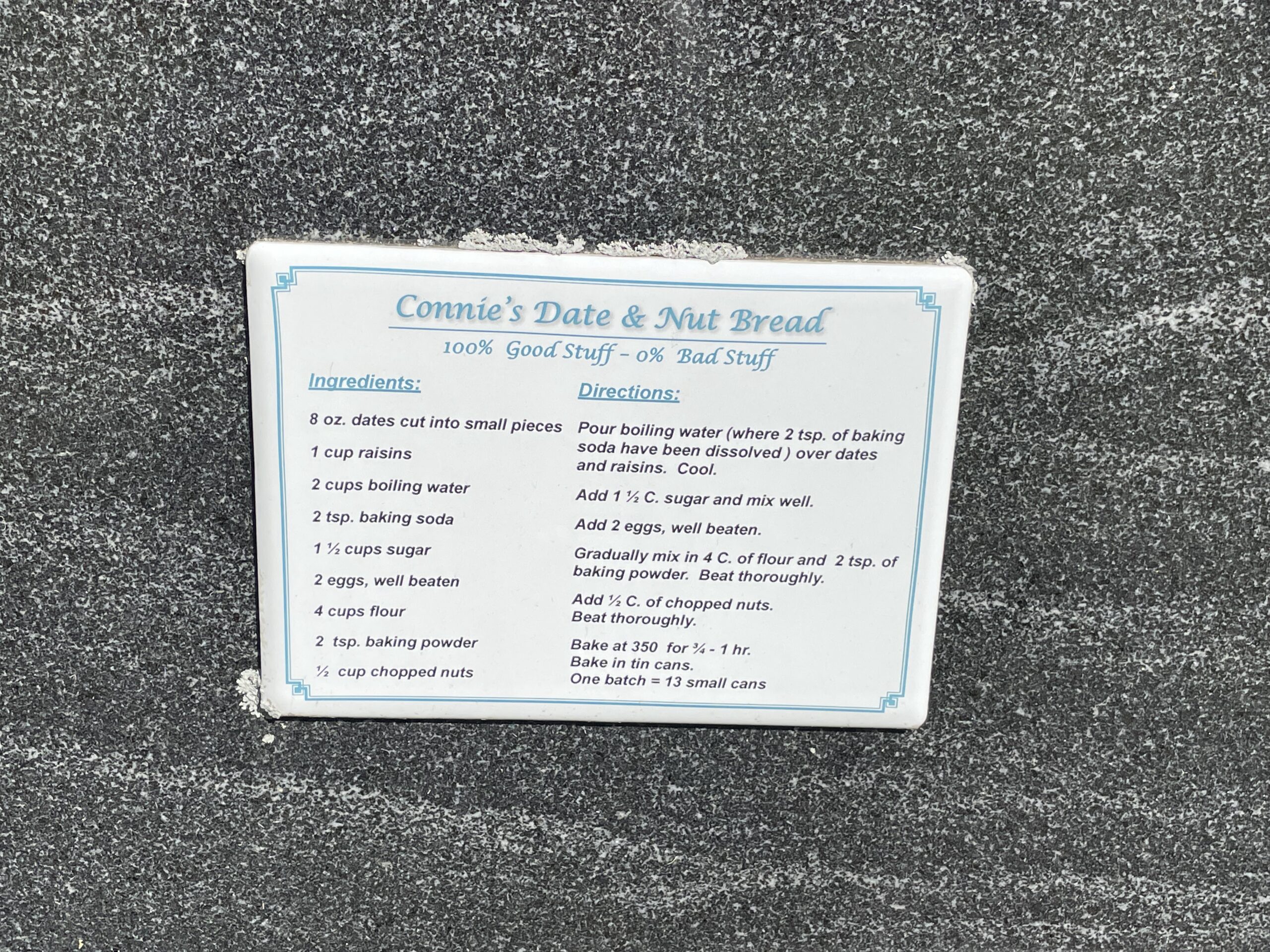

Grant began Ghostly Archive whilst studying to be a librarian at the University of Maryland. As a part of her coursework, she was tasked to create a niche social media account. She decided to take advantage of her internship at a cemetery in DC, and began documenting graveyards, where she stumbled upon gravestone recipes. During her research, Grant discovered, recorded and recreated recipes that had been immortalised on gravestones in place of epitaphs, chronicling her findings on TikTok (Ghostly Archive now also exists on Instagram). Though it would appear that this tradition of recipe epitaphs is limited to the US (Grant has found 23 graveyard recipes in total, 21 in the US and 2 in Israel), her project has garnered media attention across the globe and has sparked an important conversation surrounding the often-taboo subject of death.

The first recipe she found with such a headstone was that of one Naomi Odessa Miller-Dawson in Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery. “She has this really beautiful gravestone,” remembers Grant, “It’s just like an open book and you walk up to it and it has the ingredients for her Spritz cookies on it.” For Grant, who like many others took up cooking during the pandemic, Naomi’s recipe offered an opportunity for experimentation, “I was like ‘Oh my gosh, I wonder what that tastes like, I wonder if I can recreate this.’ I posted the process on TikTok and things really exploded.” Ghostly Projects received a slew of comments with TikTok users sharing their own family experiences and recipes, says Grant, “It was when I was learning about Naomi that I learned that there were several other people that had also [left gravestone recipes].”

As well as making the physical dishes from the gravestones, Grant also researches the creator of each recipe, interviewing their surviving family in order to find out more about each recipe and why it had been enshrined. “There’s actually one woman who’s still alive and (has already) put up her gravestone,” says Grant, “Her name is Peggy Neil. So I called her and asked, ‘Why did you do this, why did you put your sugar cookie on your gravestone?’. And she told me, ‘I was really proud of this recipe, this was something that I made for my kids and I’d send them to school with. Their teachers loved it and they’d ask for the recipe or our friends would ask for it.’ It came down to the way she wanted to be remembered. It wasn’t that she liked cooking or baking it was like, this is a recipe that I have an identity with.”

It came down to the way she wanted to be remembered. It wasn’t that she liked cooking or baking it was like, ‘This is a recipe that I have an identity with.’

It might sound strange to a younger audience to have a sense of identity associated with a recipe or food that one cooks, but in a pre-digitised, pre-internet era, recipes meant something different—they were intertwined with aspects such as culture, region or position in society. Indeed, when it comes to the Gravestone recipes, the act of passing on a special recipe seems to be synonymous with generosity. Of those who left recipes in their epitaphs, Grant found that many were women, “You could go into women and cooking and traditional roles but most of these women were, from my understanding of their obituaries and [conversations with] their families, the matriarch,” says Grant. “They hosted the family gatherings, they were the ones whose grandkids are still so emotionally connected to their memory through these dishes. They were in charge of the house and the home and that was very important to them.”

While recipes remain containers of culture, in the age of the internet, they are perhaps no longer a gift but a commodity. We now have access to thousands of recipes at our fingertips. We don’t have to call our Mom or our neighbours to pass on a list of secret ingredients, we don’t even have to buy cookbooks (although they are still very popular), we can simply search online. Though this is a privilege in many ways, it also means that physically sharing recipes has become less significant, meaningless even. Recipes are often shared online, not for the love of a really great banana bread, but to gain more likes and reads on a blog post. In the pre digital world, recipes were shared either in person or written down. The arrival of the internet, though it does give us greater access to food and food education, makes recipes vulnerable, even more ephemeral without a tangible form. Perhaps, this is why the permanence of a recipe carved out on a gravestone has resonated with so many of Ghostly Archive’s audience.

Ghostly Archive also highlights a cultural shift in how people are considering death and memory, a shift that is in part due to growing movements such as the Death Positive Movement, which encourages planning for death whilst we are still alive, rather than sweeping the idea of it under the carpet. Just like Peggy Neil, more and more of us are looking for our memorial to represent the identity that we had when we were alive. Rather than be buried with a generic description of Mother, Father, Daughter, or Son people are also choosing to embrace individuality. ”Gravestones themselves are getting more personalised,” says Grant, “If you go to a modern cemetery you’ll see anything from people’s sexual orientation, to their dogs, to their favourite book — someone [buried in the cemetery] invented a machine and [the gravestone] was just like a weird little graph of their machine.”

In the same way that there is an interesting tension between digital recipes and the tangible recipes of Ghostly Archive, there is also this new relationship between analogue and digital in graveyards as a whole. We exist so very digitally these days, that surely the digital must creep into our afterlife? We can already see examples of this in the Taoist tradition of shaozi, where paper money and paper objects are burned for loved ones who have passed on for their spirits to use in the afterlife. Traditionally, paper versions of household objects and money were offered, but offerings now include digital items such as iPads and iPhones.

“I think something that’s very interesting right now is digital memory — what happens to your Facebook and social media and instagram which (is) your personal archive that you put out into the world,” Grant says, who has found gravesites where people have found a way to bridge the physical and the digital. “Something that’s been interesting to see is QR codes on gravestones which send people to a website because a tombstone can only hold much information on an epitaph but a website can hold photos and audio.”

Digitisation of memorials could also help with the environmental impact of how we have traditionally buried our dead, particularly in the West. There are many environmental implications when it comes to burials — graves take up masses of space, embalming and preservation chemicals are harmful for the environment and the materials that we use to bury the dead can also be harmful or take a long time to break down. Though practices like cremation help on space saving, the practice still has dubious environmental implications. Would digital funerals and memorials solve at least some of the environmental implications of funerals and burials?

Importantly, Grant’s research surrounding graveyard recipes has helped to spur conversations on death and how we might like to be remembered through the lens of food. Though Covid-19 has brought the topic of death into the open slightly more, it remains a taboo subject. As Grant points out, “we’ve all come out of a pandemic for better or worse, thinking about death a little more than we might have been comfortable with as a collective… [And as we think about] what we want our legacy to look like, I think food has been a really interesting middle ground. I don’t want to talk about death with my parents, but I can go up to them and be like, ‘Hey you have this food tradition, do you want that served at your funeral?’ Whatever that is, so it’s just more of an accessible topic to see play out.”

However you may feel about your own death, perhaps continuing with traditions like passing our most important recipes on to those who come after us might offer us the same comfort that the food itself does and is yet another example of how food can act as a salve to difficult topics.