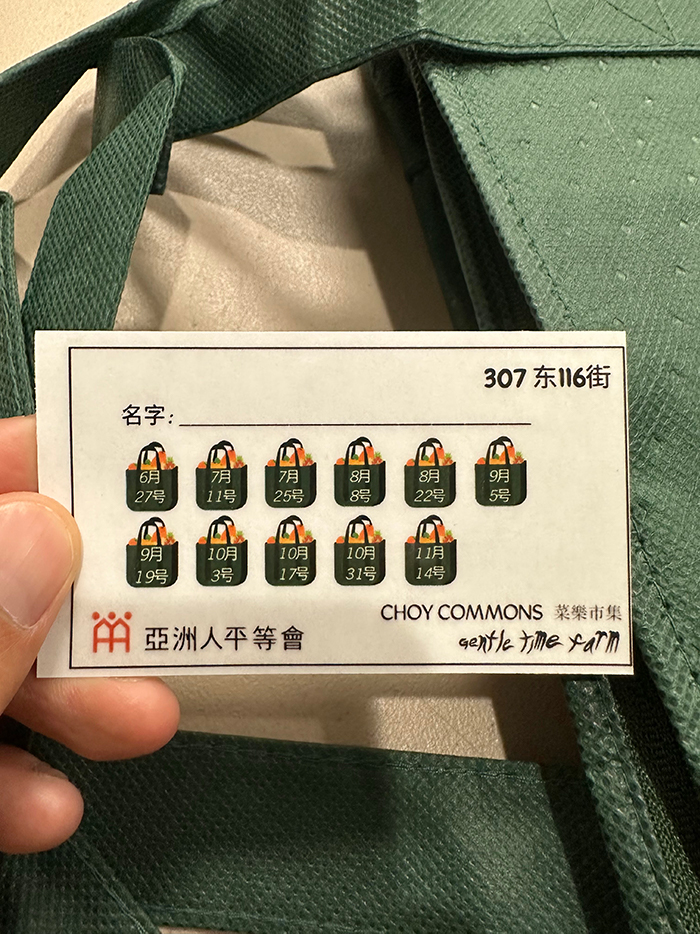

Earlier this summer, the inaugural participants of the East Harlem CSA received an unusual bounty of farm-fresh celtuce, chrysanthemum, and various choys in their shares. The new CSA, a collaborative effort between civil rights organization Asian Americans for Equality and the farming coalition Choy Commons, was created in order to provide East Harlem’s burgeoning Chinese community with culturally specific vegetables. Since the pandemic, Chinese residents have moved north to the neighborhood after being displaced from their homes due to the rapid gentrification of Manhattan’s Chinatown.1 For many, the move has been isolating, and daily tasks like going to the doctor, getting documents translated, or buying Asian groceries, now require a long commute downtown. With this program, the organizers are hoping to build new networks of care by increasing access to culturally relevant, organically-grown food for the community.

- 1. The population of Asian residents in East Harlem has increased to 9.5% from 6% a decade ago.

The program is part of a larger web of initiatives from Choy Commons, a collective of Asian American farmers and organizers aiming to engage AAPI communities in building food sovereignty across the Northeast. The idea for the collective, which currently consists of a handful of farms across upstate New York and Philadelphia, originated at the National Young Farmers conference in 2022, when attendees realized that of the affinity groups offered — Black, Latinx, queer, even Northeast and the South — there were none for Asian farmers. “We were combing the virtual participant list for any Asian last name,” Nicole Yeo of Choy Commons tells me in a recent interview with the collective, “Eventually we were able to make a space for ourselves and meet.”

Currently, only .07% of farmers in the United States identify as Asian. This is, in part, a legacy of racist policies such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, ensuing alien land laws, and the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II that not only discouraged Asian American participation in farming, but also limited Asian Americans’ access to land through land ownership.2 Through Choy Commons, participating Asian-led farms like Choy Division, Star Route Farm, and Gentle Time Farm are trying to create opportunities for Asian Americans to reconnect with land through food.

- 2. The WWII Politics of Farms and Labor, Natasha Varner.

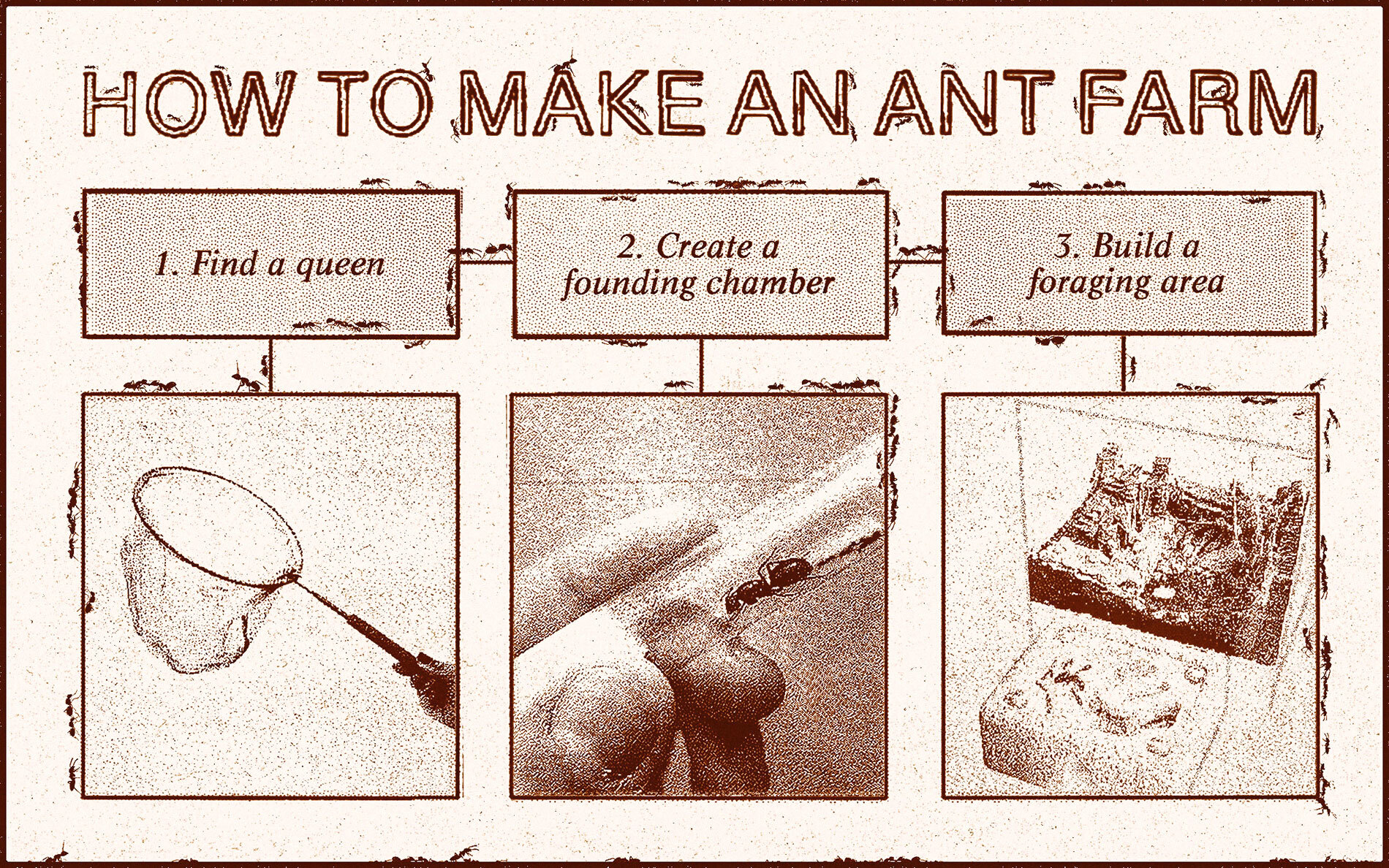

Their model is three-pronged: at the forefront of their efforts are initiatives like the East Harlem CSA, which further their goal of growing culturally specific, organic vegetables for distribution to mutual aid groups and food access programs servicing Asian communities. In order to financially support this program and their businesses, the farmers have also spearheaded a wholesale program that allows the participating small-scale farms to aggregate their resources and produce and sell directly to restaurants and distributors who use Asian vegetables. The collective also hopes to provide hands-on education to Asian farmers through their Community Farm Crew program, which assembles a regular pool of volunteers that the farms can call upon for support.

Choy Commons is, at its core, another network of support for the farmers themselves, who see models of collectivity as a necessary strategy for survival.

“One of the things we think most about is reciprocity,” says Christina Chan, farmer and owner of Choy Division, of the inspiration behind the collective’s various programs, “We want to build something that is truly collaborative and meaningful for everyone that is involved. That means all of the work we do needs to support the farm and farmers, but also the people who are receiving this food.”

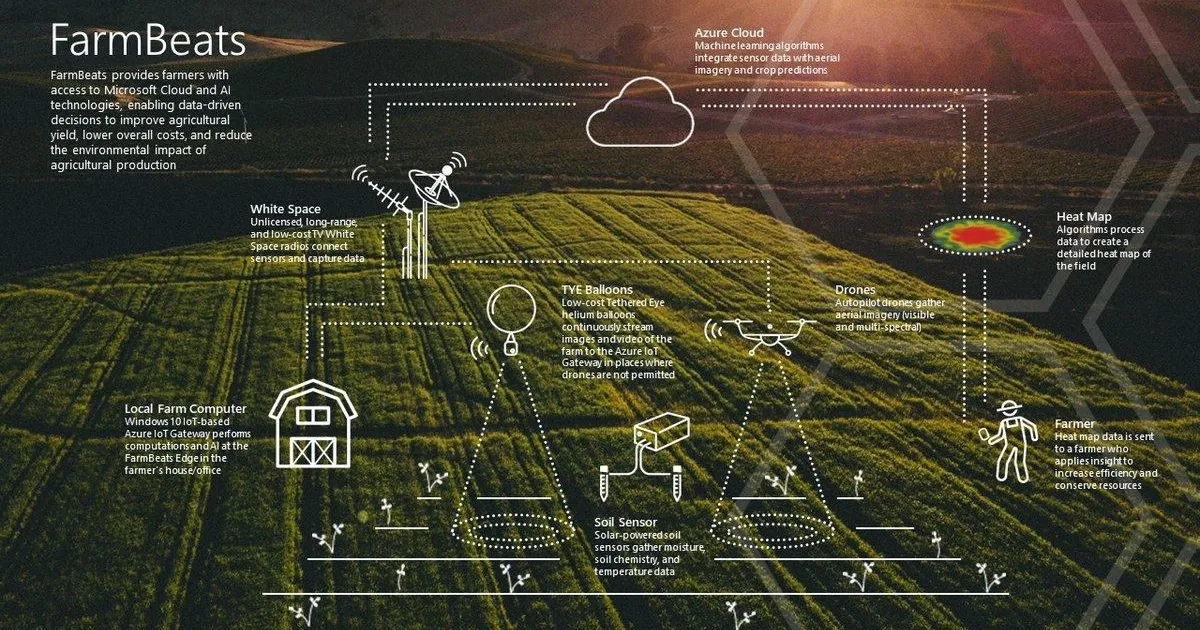

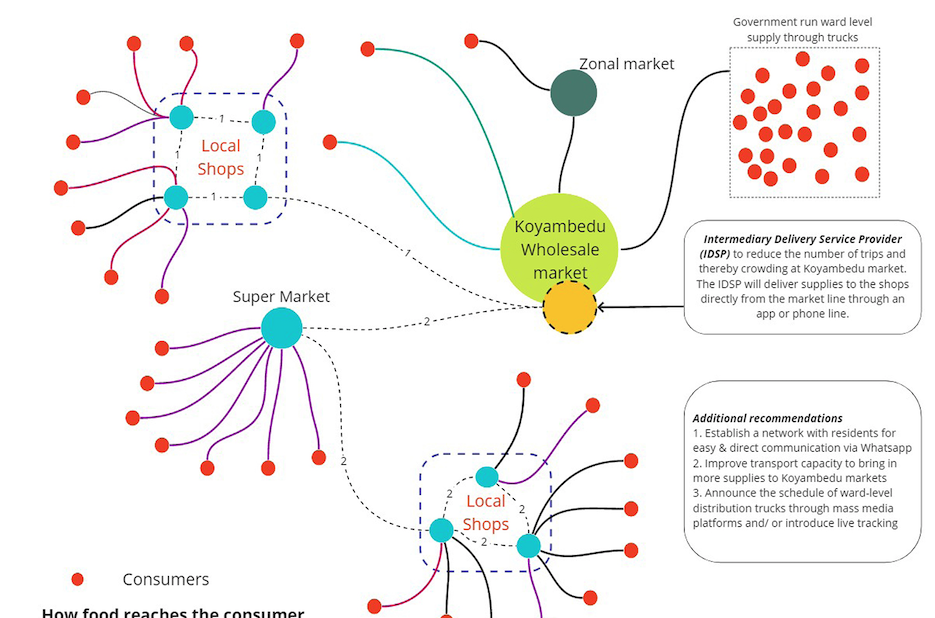

When I propose that the collective is designing a vertical food system, Larry Tse, a founding member of Choy Commons and former farmer for restaurant group DIG, suggests that their approach might be rooted in something more intuitive, “I think what it really is, is an extension of us being farmers. Farmers are trained to approach problems holistically. If one piece doesn’t work, everything falls apart.”

Choy Commons is, at its core, another network of support for the farmers themselves, who see models of collectivity as a necessary strategy for survival. The organization dovetails with other collective initiatives the participating farms are already a part of, an intimation of their larger efforts to imagine what a sustainable, alternative food system might look like. Choy Division, for example, farms on land through the Chester Agricultural Center, a farmland conservation project in New York’s historic Black Dirt region, that offers farmers affordable access to farmland through long-term land leases as well as shared farming resources. Star Route Farm also farms and organizes under the Catskills Agrarian Alliance, a coalition formed late last year between small-scale, regenerative farmers across the Catskills who, by partnering on CSA shares and wholesale, are able to support their aspirations for food sovereignty and growing produce for mutual aid groups. These interwoven systems offer new modes of resiliency, an experiment within the overarching ideology that through partnership, farmers might be able to dislodge the inheritance of land and labor exploitation that defined the first agricultural revolution. This brings them another step closer to their greater goal—the decommodification of food.

Contextualizing Choy Commons within this network of other cooperative endeavors, it becomes clear that growing food is just one part of the equation. “It’s all about logistics,” emphasizes Amanda Wong, a farmer from Star Route Farm who also coordinates transportation and storage for Choy Commons. Without the collective, the farms don’t independently produce enough to make sending trucks, which cost anywhere from $750 to $1000 a week, down to the city worth it. “We want to get these vegetables to the people who need them,” clarifies Wong, “As a farmer I’ve sold Napa [cabbage] at farmers markets where there wasn’t anyone buying — I had to kimchi most of it! At the same time you see these long lines of Cantonese elders at food distribution centers. With this collective we’re hoping to address the discrepancies of what is happening for us as farmers and what’s happening at the level of wholesalers and food pantries.”

Farming can be a lonely profession. The collective is intent on changing that. For Kaija Xiao, a farmer at Gentle Time Farm, which is in its first year of farming at its present location in upstate New York, Choy Commons has provided not only an avenue for financial stability, but also a sense of community around their principles on farming, “Small scale farming is hard. What makes it better is working cooperatively with other people who think about soil health and how we care for vegetables similarly. I’ve always seen the farm as a community space, but Choy Commons makes that viable.”

Donate to Choy Commons’ efforts or learn more about their programs here.