Endangered Kitchen explores disappearing and lesser known food practices through the lens of contemporary politics, climate change and recipes.

18 days after the United Kingdom departed from the European Union, lorries driven by Scottish fishermen hauling tonnes of shellfish rejected at European borders descended angrily on Westminster, stopping short of dumping the rotting seafood straight onto the doorstep of number 10 Downing Street, office of the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson. The enormous vehicles, painted with anti-Brexit slogans (‘Destroying the shellfish industry’ and ‘Brexit Carnage’) protested post-Brexit border issues that had recently rendered their cargo unexportable.

In the preceding months, Scottish fisheries were battered by a combination of decreasing demand for fish due to a pandemic which forced restaurants to close and a ban of British exports over Christmas after a more virulent variant of COVID-19 was detected in Britain. Then the long queues at UK/EU borders due to post-Brexit legislation meant that by the time Scottish shellfish arrived on the continent, it was no longer fit to be eaten. The ironies in this story? That one of the strongest rallying cries of the pro-Brexit campaign, to ‘take back control’ of British fishing waters, has been one of the first policies to backfire in the wake of Brexit and, furthermore, that Scotland never voted to leave the EU in the first place. Since the protests on January 18, though the UK government has supported the Scottish fishing industry with a 23 million GBP stimulus package, the EU has further tightened export restrictions, with a ban on all UK shellfish exports announced at the beginning of February. Undoubtedly, this is just the first of many crises that the post-Brexit U.K. food system now faces.

This issue however, has highlighted just how good Scotland’s produce really is—who knew that the country supplied so much seafood to champions of gastronomy like France and Spain? After working in London for 18 years, chef James Ferguson moved to Scotland’s east coast to open his pub and restaurant, The Kinnechaur Inn. His menu has a local, produce-led ethos, but upon arriving in Fife he was, “shocked at the produce—it’s second to none. I’d never realised the quality of farming and seafood, which is weird because there are a few Michelin star restaurants round here—it’s kept hidden, maybe because 98% percent of (Scottish) catch doesn’t even hit the floor of Scotland, it just goes straight to Europe…’ There’s a preconceived idea that Scotland is a barren place, when in fact, its lochs and rivers, surrounded by craggy coasts, make for plenty of excellent fish and shellfish. Its largely uninhabited land lends itself for growing vegetables, berries and soft fruits, oats and barley and remote fields are perfect for breeding prized livestock such as the Aberdeen Angus cow.

Scottish langoustines are particularly precious. “It’s one of the best and sweetest langoustines you can get in the world,’ Ferguson says. And recently, prices of Scottish shellfish, including the langoustine, have tumbled. With this drop in price, there was the question of whether Scots might start to eat more seafood. ‘‘It depends on how the relationship with the EU moves forward,’ Ferguson replied, ‘and Brits are terrible at using the diversity of fish in their waters; you can’t find native cuttlefish or turbot in supermarkets, instead we have an obsession with farmed salmon or white fish and prawns from places like Greenland. So if you gave the average person a box of live langoustines, they wouldn’t have a clue what to do with them, which is mad because they’re abundant—it should be something that’s a staple of the Scottish diet.’ Langoustines, as would most shellfish, make an excellent addition to any diet. They are high quality sources of protein, low in calories, rich in vitamins and minerals like omega 3s and B12.

So if you gave the average person a box of live langoustines, they wouldn’t have a clue what to do with them, which is mad because they’re abundant

The conversation surrounding the Scottish diet has been, in recent years, worrying. 65% of Scots are overweight and the country faces some of the lowest life expectancies in the U.K. How have nutrient dense produce and heritage dishes which very much resemble those of their longer-living Scandinavian cousins been overtaken by deep fried mars bars and neon cans of “Scotland’s other national drink,” Irn-Bru?

I put these questions to my Scottish auntie, Anne Shields, who left remote Gourock for London in the 1980s. ‘I have memories of collecting winkles by the sea and of large mussels (known as clabby dhus)—my dad used to eat them raw! It was all cheap food. But now most locals can’t afford seafood. Also a cold climate calls for hot, stodgy food – and we have a terrible sweet tooth.’ When I quizz her on traditional fish dishes—partan bree (a creamy crab and rice soup) and the wonderfully named cullen skink (potato and haddock stew) and ask whether the average Scot eats any of these on a regular basis she replies with a firm ’no chance.’ And what about the future of seafood in Scotland? ‘Well, we’ve killed most of it! Though, now there are lots of (sustainability) projects in coastal areas to leave young fish and crustaceans to develop.’ Of the fall in shellfish prices, she says ‘perhaps (us being able to eat more seafood) is the only positive thing to come out of Brexit.’

Scots voted overwhelmingly against the Brexit referendum in 2016. In 2014, they also voted against Scottish independence from the UK. But with an increasingly hostile UK foreign policy that Scotland does not agree with, there have been rumblings of a second independence referendum. Would Scotland be able to go it alone? Perhaps. Not only does it have access to oil, gas and renewable energy sources in the North Sea, in 2018 and 2019, Scotland was the fastest growing economy in the UK, it’s 2018 growth mainly down to a jump in exports of food and drink.

Various government funded bodies now recognise the importance of food to Scotland’s growth, and that gastro-tourism could help in the recovery after both Covid-19 and Brexit. In an attempt to understand modern food landscapes projects such as Food Heritage Scotland seeks answers in a cross-country survey that aims to ‘uncover Scotland’s hidden food heritage.’ The survey asks ‘people across Scotland to rummage in family recipe books… and to share recommendations of local produce.’ If using research like this helps to join the dots between helping an unstable economic future, a shifting political landscape, a dying fishing industry and pre-existing health and environmental issues, could using food systems create a circular economy that could potentially improve all of these problems? By finding their own culinary voice, the Scottish people may just be able to chart their own waters through the complicated storm that undoubtedly lies ahead.

Recipe: What on earth do I do with langoustines?

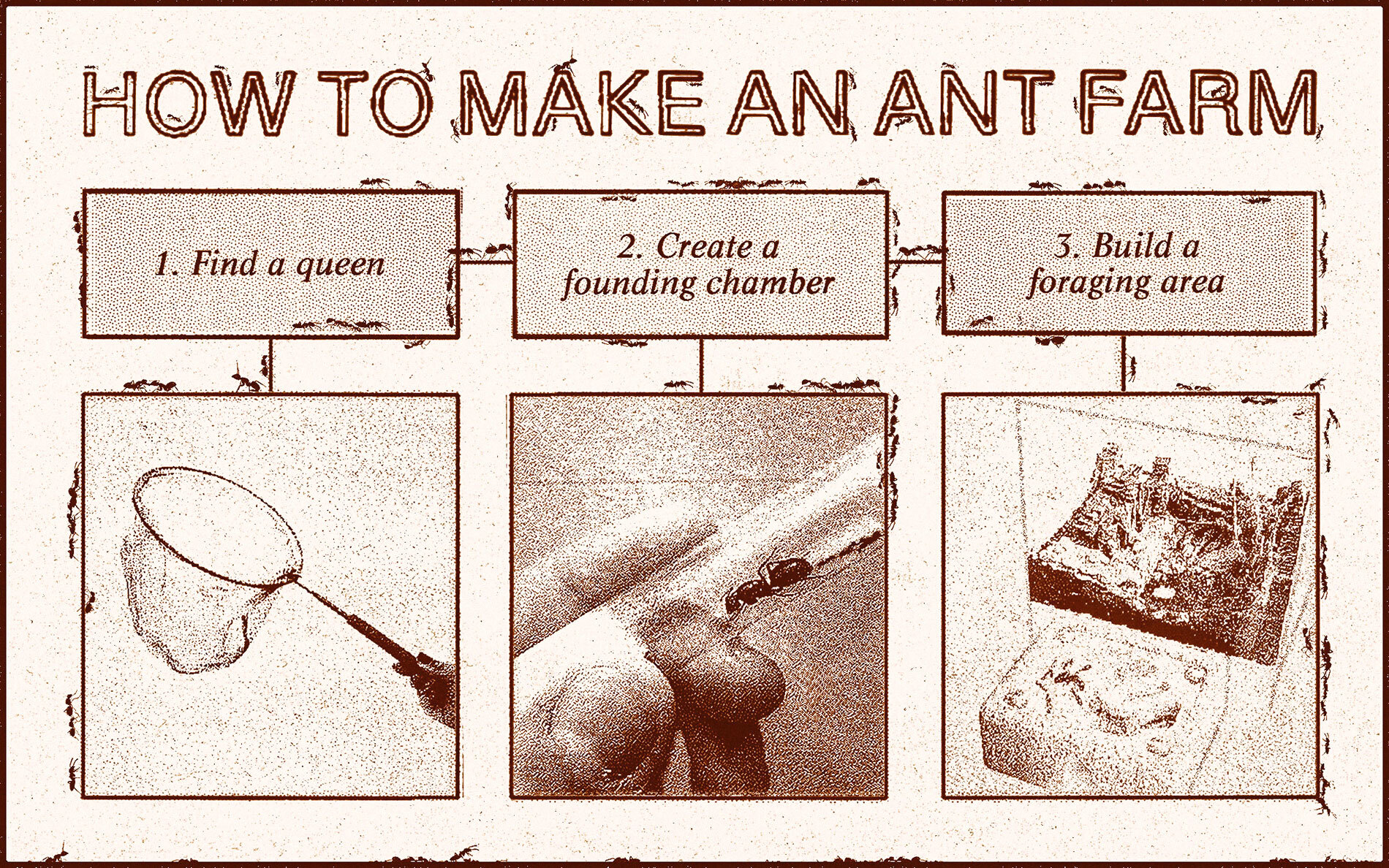

(How to buy, prepare and cook langoustines)

How to cook them

- Don’t panic. They look creepy, but they’re delicious.

- If they are still alive, put them in the freezer to stun them for at least two hours (preferably overnight).

- Salt a pot of water and bring to the boil.

- In batches so you don’t crowd the pot, boil the langoustines for about 4 minutes each. You’ll know they’re ready as their shells will turn pink or white from a translucent/grey colour.

- Drain the water and peel.

How to peel them

- Start by removing the head – this should be easy, just twist it slightly to one side. You can either suck out the meat from the head or you can keep to make a fish broth (see below).

- Pull off the claws and either suck out the meat or crack them with a nutcracker. It’s a bit fiddly, so I recommend using these for fish broth also, as they add a lot of flavour.

- Starting from the ‘neck’ of the langoustine, peel the shell by starting in the middle and making a kind of ‘unbuttoning’ movement, ending with the tail.

What to eat them with

- Dipped in whiskey aioli as a snack or starter to a main meal. (For the aioli whisk or blitz 2 egg yolks, half a lemon, 2 tsp mustard, a glug of whiskey and garlic, slowly adding in 250 g olive oil while whisking until thick and mayo-like).

- Lightly fry the langoustine meat for a couple of minutes in some olive oil and garlic and eat with kale that has been boiled or steamed for 15 minutes and dressed with olive oil, pepper and plenty of lemon juice.

- Baked into a mac and cheese.

- Lightly fry with some parsley, crushed garlic cloves and chilis and add to a spaghetti dish.

What to do with the shells

- You don’t get a huge amount of meat from langoustines, but you can make your efforts worth it by also making a delicious langoustine stock.

- Place all the discarded shells and heads in a pot, with crushed garlic cloves, chopped onions, herbs such as parsley and coriander, peppers, bay leaves and chopped celery as well as a good glug of olive oil.

- Fry your ingredients for about 5 minutes on a medium heat.

- Pour over cold water so that the water just covers the ingredients, add a halved lemon and bring to the boil.

- Once boiled, simmer for 35 minutes. Strain out the shells and herbs. Keeps in the fridge for 3 days.