San Francisco’s Portola neighborhood, located in the southeastern part of the city, first earned its moniker as “The Garden District” for the abundance of family-owned nurseries that once populated the area. In the 1920’s, the Portola was home to 19 nurseries which, in addition to growing produce, produced the majority of the cut flowers sold in the city. By the 90’s all of these operations had shuttered as land values skyrocketed and agriculture was pushed out of the city. However, a new community-led initiative aims to reclaim Portola’s rich history of urban agriculture by transforming the neighborhood’s last standing greenhouse site into a community agriculture center.

Locals used to call the site at 770 Woolsey the Rose Factory1. The lot’s 2.2 acres of overgrown grass and thorny blackberry bushes are dotted with skeletal structures, the remains of the once-whitewashed greenhouses that the previous owners of the space, the Garibaldi family, used to cultivate the city’s roses in. In 2012, this seemingly abandoned lot captured the imagination of a local group of activists and residents who saw the land as an opportunity to create a hub for food education and production for the Portola neighborhood. The group sought to restore the lot into a working farm, eventually forming The Greenhouse Project to bring the dream into reality.

- 1. Hidden Histories: University Mound Nursery, Curbed, 2012.

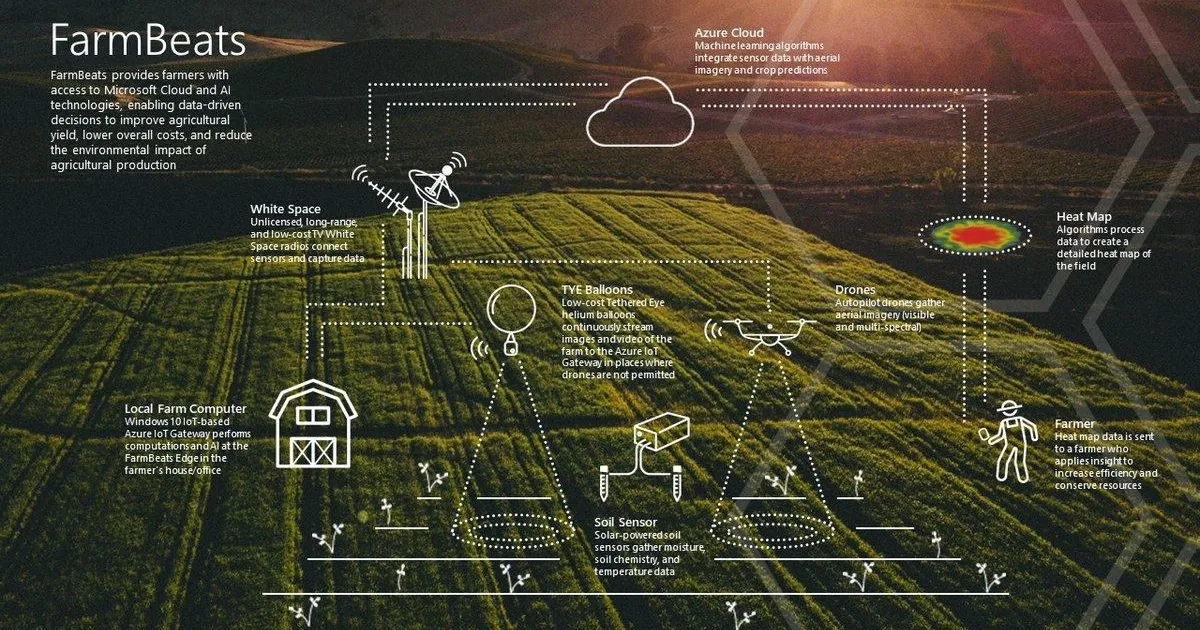

The Greenhouse Project asks if urban agriculture can serve as a viable path for food production within city limits. Organizers hope that through this project, urban agriculture can be used to collapse the distance between Portola residents and their food systems by increasing transparency in how food production works. The vision for The Greenhouse Project joins the ranks of a larger movement of Bay Area initiatives such as the neighboring Florence Fang Community Farm and Alemany Farm, home to the Two Eighty Project, that are experimenting with what community-centered urban agriculture looks like.

For Caitlyn Galloway, a board member of The Greenhouse Project and the former founder of Little City Gardens, this project serves as an opportunity to reimagine a more sustainable model for urban agriculture, “Just because it’s in the city, doesn’t mean it can’t be a working farm. If urban agriculture always stays rooted in a volunteer-based kind of realm, then it’s always going to be a novel idea rooted in a place of privilege for people who have the time and resources to volunteer.”

Of course, in a neighborhood cradled in between two of the Bay’s vital arteries— I-280 and 101— the lot is also a lucrative site for real estate developers. In 2017, the land was sold to developers for $7.5 million dollars to be turned into a 62-unit housing development consisting of market-rate condos. This sale inevitably faced backlash from a community that had been organizing for almost a decade around the lot. Eventually a deal was brokered in 2021 providing Friends of 770 Woolsey, a nonprofit that works in tandem with The Greenhouse Project, with the legal right to purchase the property for $8.5 million dollars. Currently, the nonprofits are in the final stretch of fundraising with the deadline to buy the property approaching in June.

By purchasing this land, The Greenhouse Project hopes to secure the accessibility and sustainability of the space for the community in the long-term. In many cases, urban agriculture projects have been treated as temporary solutions, interventions that bring conviviality, community and nourishment to a space only to be evicted when the land appreciates in value (in most cases, due to the vibrant community that has grown up around it). However, it has become clear that a more permanent solution is necessary in order for urban agriculture to realize its larger goals of community building, climate education, and creating more resilient food systems.

The Greenhouse Project is part of a larger movement by local nonprofits and community organizations to “green” Portola. A report titled the Portola Green Plan2, outlines a vision for the community that includes initiatives such as “daylighting” the Yosemite Creek and creating a green corridor, of which the Greenhouse Project is a part of, across the neighborhood from the historic Allemany Farmers Market to McLaren Park. According to Galloway, these individual steps are a part of a greater, community-led effort to bolster the community’s agricultural identity and provide long-term residents with a sense of place in the face of San Francisco’s rapid gentrification.

The organizers behind Friends of 770 Woolsey and The Greenhouse Project have been careful in navigating the fraught relationship between green space and gentrification by establishing a robust community outreach process within their visioning for the future of the space. Academically referred to as “the green space paradox”, the development of green infrastructure, gardens and parks in urban areas previously under-resourced in terms of green space has a history of contributing to rising real estate prices and displacement.

“Urban agriculture definitely runs the risk of exacerbating [these dynamics],” says Galloway, “In order to mitigate the farm’s role in displacement, we have really centered partnering with community organizations as well as incorporating community voices to make sure that this space reflects what residents actually want to see.”

Studies have shown that green spaces that are managed by community organizations like ‘Friends of’ groups, as opposed to those that are privately managed, run less of a risk of accelerating displacement3. The project’s organizers have also begun exploring models of community ownership to ensure the longevity and communal sustainability of the project.

Gardening is, in itself, an exercise in managing change. Each action — the sowing of seeds, watering, weeding, waiting, harvesting — is a marker of a greater shift taking place. For Galloway, the importance of The Greenhouse Project lies in its ability to offer local residents the opportunity to build a relationship to change and to create a space that engenders the local community with a sense of agency over their collective future, “San Francisco is changing so quickly and I think people feel kind of helpless against that change. So I think what’s going on in this community which already has a history of using gardening as a means of connection, is an attempt to have some sort of agency around what the change looks like and who is part of deciding the change.”