Removing the kitchen from the home forges an architecture of resistance. It is an architecture where cooking does not solely form part of a domestic and private realm, but happens openly and publicly to form a metropolitan organization that aims to have a political voice.1 The adverse reaction to eliminating the kitchen from the house brings to light the assumptions the space provokes.

- 1. Anna Puigjaner 2022

If the kitchen is removed, could the home exist as a space completely free of prescription? By design, the kitchen is a space where women take responsibility for domestic work alone amidst a care-based system of social value, rather than one of economic gain.2 By effect, the kitchen itself has had a main role in defining the home and the family. In understanding its construction we are then able to question its ability to be reversed or changed. Could the kitchenless home celebrate domestic work in society rather than covering it with a veil?

- 2. See the Frankfurt Kitchen by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, designed “to rationalize the housewife’s work”

A kitchenless city is the extension of the kitchen homespace, by and for the community. The model is abundant globally, and for the most part, run by families and largely managed by women who were previously unemployed, as worker-led initiatives. Kitchens in this model enable ownership and establish a connection to society for those who work there. Not exclusively idealistic, but presently realized; the following are a few urban examples of kitchenless stories.

In the early 1900s, two movements united to redesign the American home: socialists called for the proper and equal compensation of domestic work, and feminists, such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman, aimed to free women from the subjugation of housework. In Women and Economics, Gilman writes:

“Take the kitchens out of the house, and you leave rooms open to any form of arrangement and extension; and the occupancy of them does not mean ‘housekeeping.’ In such living, personal character and taste would flower as never before… The individual will learn to feel herself as an integral part of the social structure, in close, direct, permanent connection with the needs and uses of society.”

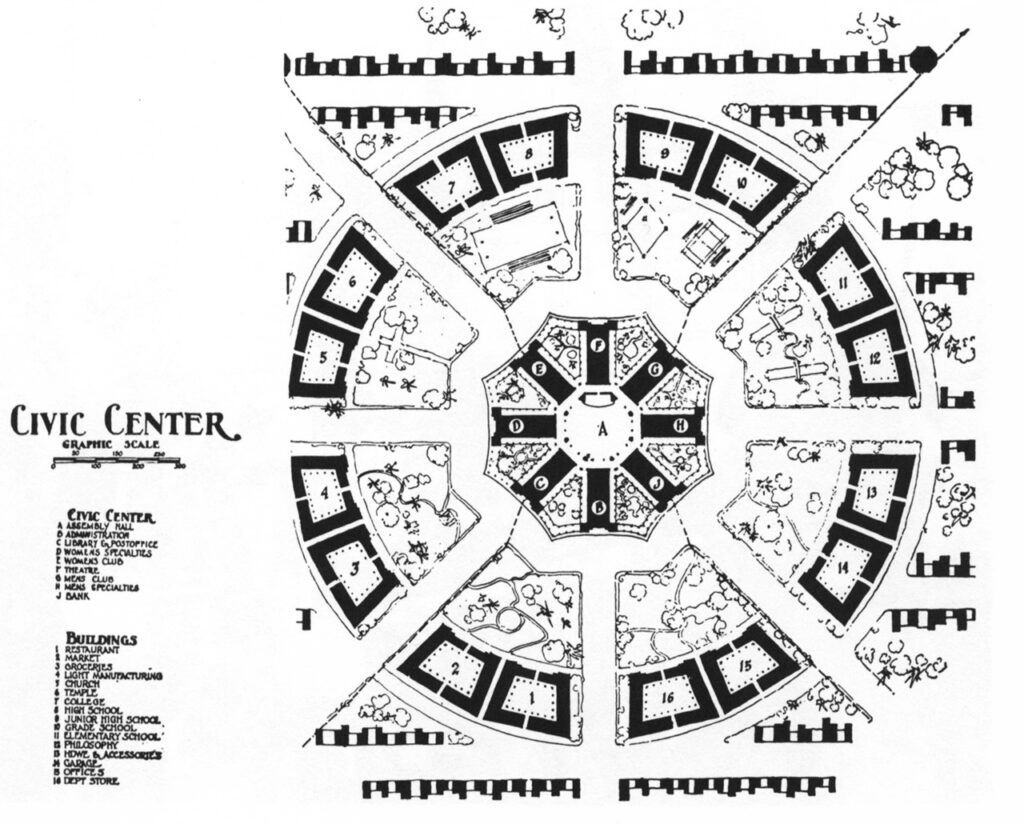

Self-taught architect, Alice Constance Austin would put this theory to practice in 1911 as she planned the kitchenless community of Antelope Valley, Los Angeles. The model was simple and automated albeit sci-fi. It planned to house 900 people who, on a rotating basis, would service a centralized kitchen; meals and laundry would be delivered through an underground conveyor belt and dirty dishes and clothes returned in the same manner, housework would exist as a community effort.

Across the coast, in New York City, the age of apartment comes into play; communes of a different kind. Individual units within a building would host kitchenettes, meant to cook for pleasure; and a full service kitchen would take the ground floor, manned by a chef and staff. The idea saw cooking as a profession, best left to professionals; as well as an attempt to turn opinions on apartment living by offering such amenities. Despite this happening towards the end of the 1900s, it is most like the kitchenless cities of today.

“When you’re alone, it’s easier to be ignorant of your potential. You don’t know your powers, your strengths, what you’re capable of,” says Melanie Lamoureux, one of three women responsible for bringing collective kitchens to Montreal in 1985.3 With limited time and money plus families to feed, the three decided to split the costs and labor by purchasing food in bulk and cooking together for an afternoon. In just three years of their activism, at least twenty collective kitchens formed under the lobby Regroupement des cuisines collectives du Québec (RCCQ.)

- 3. The Tyee 2007

The trio journeyed to Peru in hopes of learning from international kitchenless cities. In Lima, they met the Comedores Populares, a faction of self-initiated communal kitchens. At the end of the 1970s, during a period of great social politicization, the national teachers union occupied local schools protesting for better wages. In solidarity with protestors, women of local communities collectively prepared pots of food for them. For weeks, schools became sites of political discussion, and the women cooking for the protestors gained a voice and an awareness of their political power.

Once this system was in place, the need for it became apparent. Hence, Comedores Populares was founded and focused on providing food for their families and the community on a large scale. They host satellite kitchens networked across Lima operating as an official, organized partnership. They are self-funded and deny economic assistance offered from the government in exchange for political support. For they feel that trading allegiance for assistance would sacrifice the freedom and independence they originated from. Today, Comedores Populares employs more than one hundred thousand women cooking for the community feeding nearly half a million people per day.

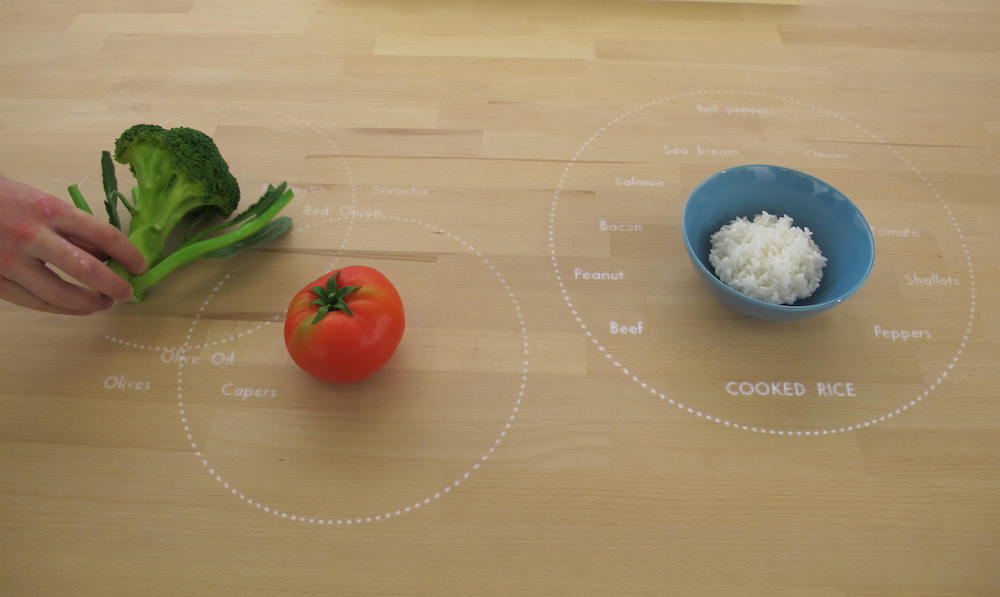

In other circumstances, the government initiates social projects such as collective kitchens to introduce financial initiative and promote community participation. In 2009, the government of Mexico City initiated Comedor Comunitario, promoting half public, half private collective kitchens. To apply you need only to be a citizen with a room larger than 30m2. If accepted, the city will install an industrial kitchen supplied with cookware and subsidize non-perishable food delivery, like rice or beans, on a bi-weekly basis. In exchange, the kitchen will cook daily menus for their community in their home. Since the program was initiated, hundreds of homes in Mexico City have been retrofitted to house communal kitchens and dining space. The architectural intervention is minimal; a kitchen may be a tidied garage, or a patio fashioned as a dining room by means of a simple tarp covering. Kitchens existing once as a private space have found function as collective spaces.

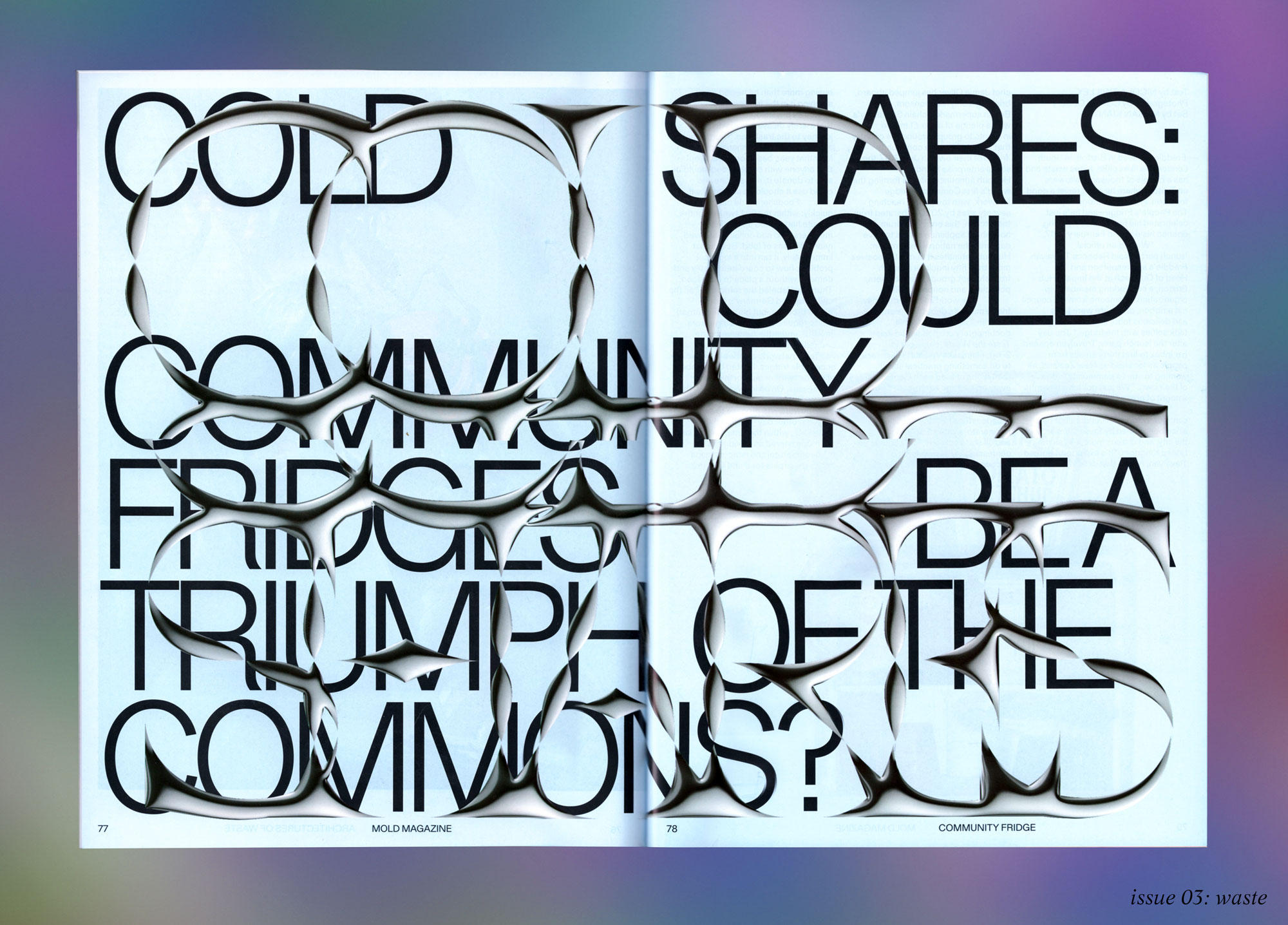

The potential futures of the kitchen lives within these practicing kitchenless cities. They blur private and public, and celebrate labors of love. Akin to the gestures of a host to their guest; they are extensions of the home into the city. What’s interesting is not so much the communal kitchen itself but the impact it has directly on the communities and those who use them. They aren’t solely an idealized attempt at utopia; they come from a need. They operate under low-tech facades, exist beyond the publicity of restaurants, and are spaces of caring for the community by the community through the power of food.