This story was first published in print for MOLD Magazine: Waste. Order the whole issue here.

Freddie is based in Brixton, in South London. He likes cake, hates waste and has a couple of thousand followers on Twitter, where he can’t resist a good food pun. He’s also a fridge—specifically, The People’s Fridge—and he’s just celebrated his first birthday, having opened his doors in February 2017.

“We had an official launch party,” said Rebecca Trevalyan, Freddie’s spokesperson and Head of Outreach at the Impact Hub Brixton, a co-working membership organization. “Someone from the council cut a ribbon, and there were talks and delicious food, and then everyone took selfies with the fridge.” The day after the launch party, Trevalyan opened her inbox to find thirty emails from people as far afield as New Zealand, all wanting to start a community fridge of their own. “We just got a tremendous amount of press,” she explained.

Freddie may have been the first community fridge in London, but he’s since been joined by four others around the city, and dozens more across the United Kingdom. “It’s exploded,” agreed Trevalyan, noting that celebrity chef Jamie Oliver has jumped aboard, bringing along his sponsors, British supermarket chain Sainsbury’s, with a pledge of up to £1 million in grants to groups around the country that want to launch a community fridge of their own. In July 2017, the social enterprise foundation Hubbub announced it was forming the world’s first Community Fridge Network, with the goal of reaching seventy sites by 2020. Liberated from the kitchen, this once humdrum household appliance seems to have captured the national imagination: Hubbub estimates it currently receives more than fifty inquiries a month from student groups, shop owners, politicians and nonprofits alike.

The world’s first community fridge made its debut five years ago, in Berlin, Germany. After his documentary on global food waste, Taste the Waste, came out in 2010, filmmaker Valentin Thurn decided to do something practical about the 176 lbs of food each German throws away on average each year. “The fridge is a kind of mood pharmacy,” Thurn told Deutsche Welle, Germany’s public broadcaster, in 2012. “We fill our refrigerators with stimulating, soothing and all sorts of foods,” he continued, confessing to his own habit of succumbing to impulse purchases, buying more than he needed and stashing it in the fridge—a psychological as well as physiological buffer zone that merely delayed its inevitable journey to the trash can. Thurn launched a peer-to-peer food-sharing platform later that year, based on the concept that anyone with surplus food should be able to donate it, and anyone who could use it should be able to take it.

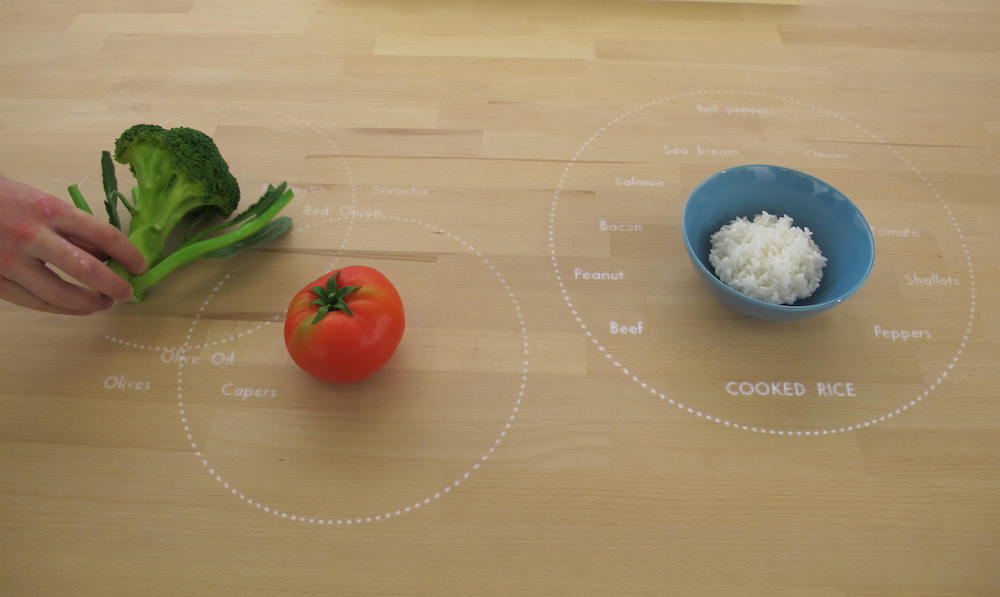

Foodsharing.de caught on quickly: within the first twelve months, the site had signed up 30,000 members who had collectively saved nearly 30 tons of food. But, almost immediately, it ran into a logistical problem: how to coordinate supply and demand without a place to store food. Thurn had labeled the refrigerator as the culprit behind Germany’s food waste problem, but his solution turned out to require yet more refrigerators. In 2013, under the foodsharing.de umbrella, Thurn established the FairTeiler network: a series of publicly accessible fridges, hosted by members of the network or supportive local businesses. On an individual level, the refrigerator’s time-distorting superpowers—its promise to save food for some other day—might enable waste, but, within the community at large, the fridge served as a bridge, filling the geographical and temporal gaps between surplus food and its eaters.

Over the following years, the idea of the community fridge began to spread. In spring 2015, in Galdakao, a small town on the outskirts of Bilbao, Spain, volunteers put a large white fridge on a sidewalk, built a wooden fence around it, and launched it as the country’s first “solidarity fridge.” By 2016, there was a community fridge in Frome, a historic market town in Somerset, England, and one nicknamed namma maram or “tree of goodness,” in the port city of Kochi, in Kerala, India. Curiously, it was the latter that provided the inspiration for Freddie’s founders: in May 2016, Impact Hub Brixton convened a meeting of activists from around the borough to discuss what was missing from the local food system, and someone mentioned an article they’d read about a community fridge in India. “Basically, we were all like, Oh, we should do that—that looks great!” said Rebecca Trevalyan. “Why doesn’t that exist already?”

On a Tuesday morning in July when I visited, Freddie’s shelves were filled with day-old sourdough bread, four zucchini, and a sack of potatoes. “That’s pretty normal,” Trevalyan told me. “We did have some truffle oil in there at one point, and a Christmas pudding in April, which was weird.” Most of the food comes and goes within twenty-four hours, according to Trevalyan, and most comes from businesses rather than individuals. A nearby branch of Pret-a-Manger drops off leftover sandwiches at the end of the day, and a local cinema will put in pastries, “like homemade almond and orange cake and big piles of brownies and stuff,” Trevalyan said. “They don’t stay around very long.” Frequently, the foods in the fridge don’t actually need to be refrigerated—Freddie is as likely to contain cans and cereal boxes as milk—and Trevalyan told me that she’d love to set up a “People’s Pantry” next door, when time and funding permit.

Similarly, the Impact Hub team hopes to conduct a detailed survey to see exactly who is using the fridge. The group spent time talking about the fridge with local traders, restaurants, and food businesses to secure their participation ahead of its launch, and Trevalyan said that she’s since personally met and talked to lots of users. “It ranges from people who work in the area who are just popping by to get a loaf of bread, to families who come along to see what fruit and veg is in there, because food banks don’t have fresh food generally,” she told me. Despite this anecdotal evidence that the food in the People’s Fridge is, in fact, going to the people who need it most, Trevalyan is quick to point out that it “is not a solution to food poverty”—and nor is it intended to be. Plastered to Freddie’s front is a sign saying that he is a “Judgment-Free Zone,” meaning that there is no need to show proof of hunger or need to take from the fridge. Similar principles inform the majority of Europe’s community fridges. “It doesn’t matter who takes it—Julio Iglesias could stop by and take the food,” Álvaro Saiz, organizer of Galdakao’s Solidarity Fridge, told The Guardian. “At the end of the day, it’s about recovering the value of food products and fighting against waste.”

In India, which is home to a quarter of the world’s undernourished population and where fewer than thirty percent of families own a refrigerator, community fridges are equally popular, but operate on a slightly different basis. Decorated with garlands of marigolds, a steel fridge on the edge of a busy Mumbai street is typical. It offers donations of homemade dhal, vada pav (fried potato sandwiches) and poha, or flattened rice. Its organizer, a local community group, wanted “to create an atmosphere where people could live with dignity and weren’t forced to beg.” Reducing food waste was a secondary goal.

But while the logic of the community fridge is immediately appealing in either context, actually setting one up is significantly easier in India than in Europe, where public health authorities have generally struggled with a community fridge’s inherent lack of ownership and distributed management structure. In Berlin, food inspectors declared that the city’s FairTeiler fridge network posed a health hazard in early 2017, reporting “unhygienic conditions,” including unpackaged bread. At least one of Berlin’s twenty-five community fridges shut up shop in response. In Brixton, Trevalyan told me that Freddie’s intended location, on the street, had been vetoed by the council—he now lives inside a local event space, and is locked up at night. Raw meat, fish, and eggs are all excluded from the fridge due to fears of contamination, and cooked food can only come from registered food businesses, rather than individuals.

A team of volunteers check the food, monitor the temperature, and clean the fridge every morning and every evening, and both food donors and food users have to sign a logbook so that the council can see what food has come in and gone out, and when. “They want full control,” explained Trevalyan “They say, if you’re measuring your risks, you’re managing them. Whereas with this, the point is that people manage themselves.”

To anyone who has had the misfortune of having their lunch stolen from the office fridge, or witnessed the inability of a dorm full of students to clean up spills and sticky patches in their shared kitchen, this idea—that people will manage themselves—will likely set off alarm bells. Certainly, to me, a shared fridge seemed like a tragedy of the commons waiting to happen. But that hasn’t been the case, according to Trevalyan. “People always assume it will be far worse than it is, from my experience,” she chided me. “Good social design is getting people to act in the interest of the collective without explicitly asking them to,” she explained. “And I think if you design services like this correctly, with the kind of storytelling and signage and subtle nudges to make people act the right way, then they generally do.” In Freddie’s first few months, Trevalyan says she’s already learned valuable lessons about the scale and geography at which a community fridge operates best, which is “hyperlocal—like a one- or two-minute walk, max.” She’s found that, at the end of a long shift, workers in local food businesses are unlikely to walk further than that to drop off excess food. Similarly, within the first few months, the team redesigned the fridge logbook signage to make it even simpler and less wordy. Basically, people will not do anything unless you make it really easy and really obvious,” Trevalyan said.

For Trevalyan, who also runs another sharing initiative called The Library of Things, which loans out useful items such as power tools, this is perhaps the most exciting aspect of Freddie’s impact. Helping reduce food waste, helping those in need find food—these are important and valuable achievements in their own right. But figuring out how to build and maintain a community-owned, shared resource? “That,” she told me, “would be powerful.”