MOLD’s series Health. Food. examines narratives around food and healing. Particularly how food feeds into the ongoing maintenance of our bodies, communities, and the Earth.

What goes into a $200 peanut butter and jelly sandwich? That’s the question private celebrity chef Brooke Baevsky asks in a recent TikTok video where she breaks down the prices of her Erewhon grocery list for the expensive sandwich. In part satirical, the clip breaks down how the Los Angeles grocery chain has earned its viral reputation as “America’s Most Expensive Grocery Store”— a sprouted buckwheat boule goes for $25, a jug of Erewhon-branded, ‘oxygenated’ water (she uses it to make the homemade jam) comes in at $30.

It makes sense then, that the grocery store’s core audience are the rich and famous—or those who want to eat like the rich and famous. In the age of Goop, the cult of wellness is inextricable from the cult of celebrity, something Erewhon has capitalized on with its celebrity-endorsed, adaptogen-infused smoothies and supplements. In a sense, the grocery store has become a wellness amusement park for the rich. Within this arena, holistic tools for health that communities across the world have always relied on—like eating only according to what the land around us might provide, herbal medicines, and indigenous healing traditions—slip into the category of luxury. The continued commodification of holistic health practices takes on bleak dimensions when contextualized by America’s broken, opaque healthcare system. Erewhon is undeniably shaping how Gen Z and future generations think and talk about food. What might come as a surprise to recent devotees is that the store and its stewards have been doing it for over fifty years.

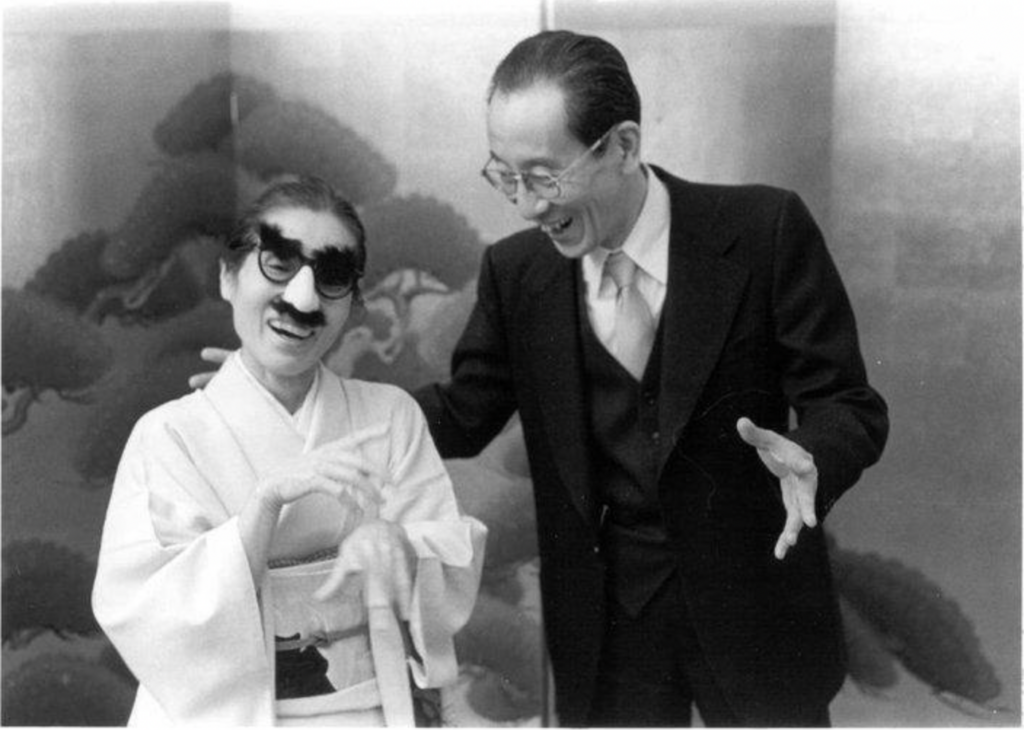

George Ohsawa’s World Government Association

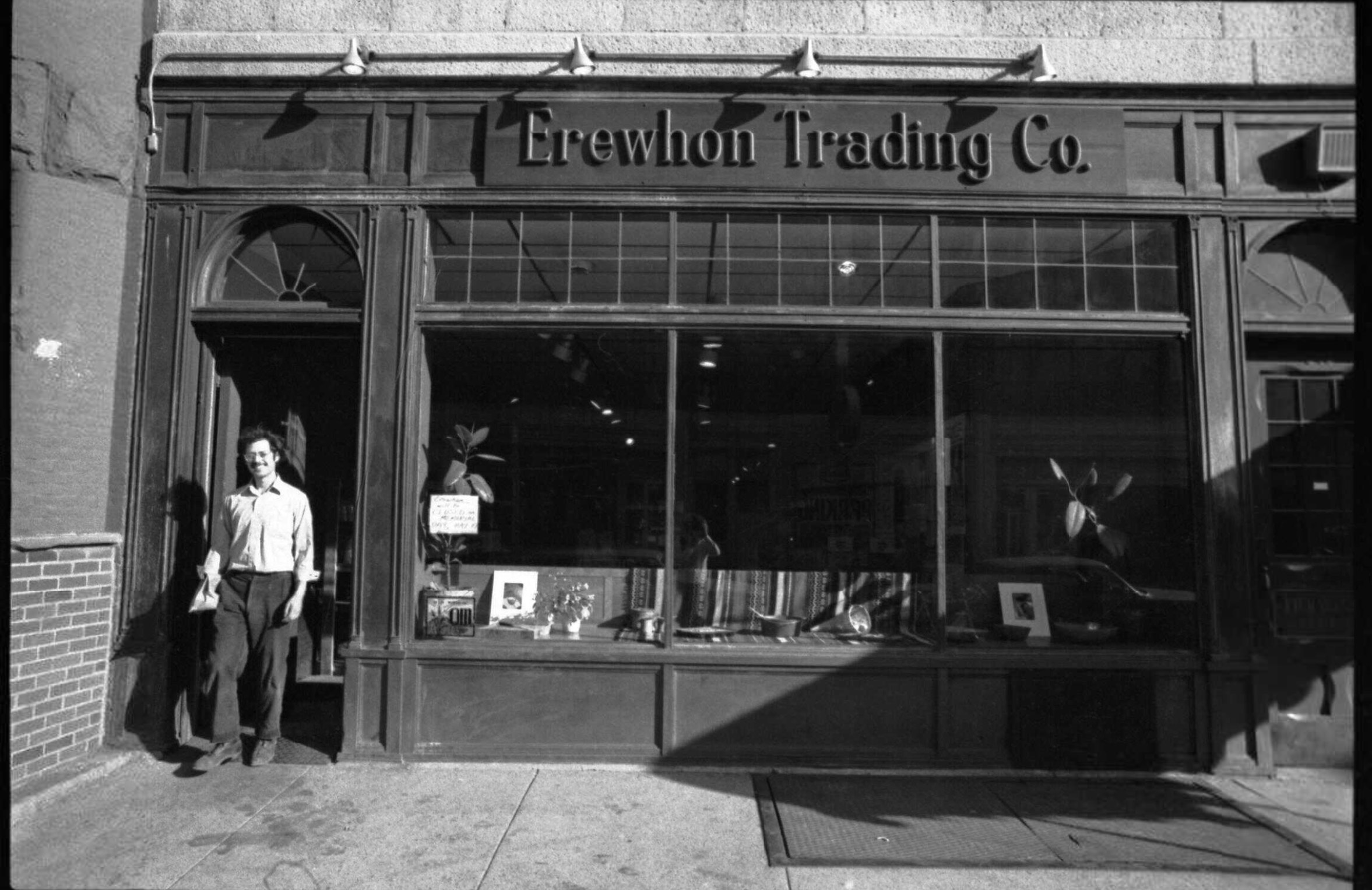

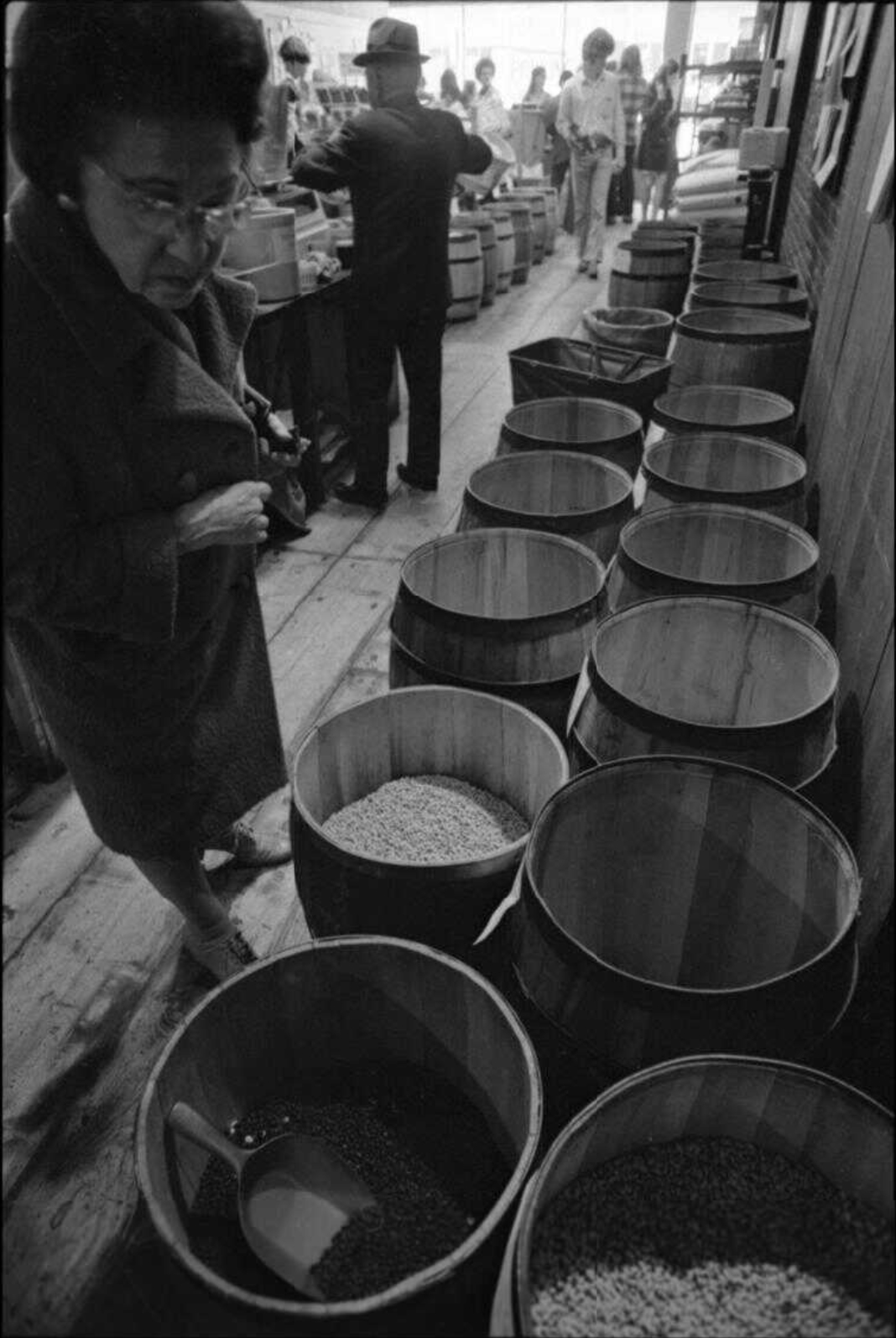

When Erewhon was first created, its founders believed that it would bring about world peace—or at least help. Aveline and Michio Kushi opened the doors to the original Erewhon store, then based out of Boston, in 1966. The store was named after Samuel Butler’s 1872 satirical utopian novel, Erewhon—an anagram for ‘nowhere’. Located in a basement storefront on Newbury Street, Erewhon operated more as a food collective than a grocery store, hawking a slim selection of organic grains, beans, and soy products imported from Japan to Boston’s more granola ilk. One of the earliest natural foods stores in the country, Erewhon’s bulk food bins and solid wooden interiors would serve as a template for the health and natural foods that many know today. While the couple would eventually be hailed as the pioneers of the macrobiotic diet in the United States, at that time they were simply dedicated disciples attempting to further the teachings of George Ohsawa’s World Government Association in the West.

Founded in Japan, the World Government Association was organized around the belief that political change was achievable through food and its methods of consumption. Ohsawa, best known today as the father of macrobiotics, created the school in affiliation with the World Federalist Movement, a group of peace-minded individuals and international organizations (which counted Einstein and Sartre amongst its members) advocating to unite the world under a single federal government system. Both Aveline and Michio were drawn to Ohsawa’s teachings because of their experiences living in Japan during World War II. Michio, at that time a soldier stationed in the south of Japan, witnessed the destruction of Hiroshima first-hand from the windows of a train shuttling soldiers back to Tokyo following the detonation of the atomic bomb, and would carry these harrowing images throughout his life’s work.

The Kushis’ anti-war efforts were at first focused on policy — advocating for anti-war legislation and a universal constitution for a world government. However, facing ideological roadblocks, they soon followed in the footsteps of their teacher, Ohsawa, turning their attention toward food. In an interview with MOLD, Aveline and Michio’s son, Phiya Kushi explains that his parents had to come to terms with the reality that without understanding human nature, a world government would only promote the expansion of a police state that might incite further violence, “In order to get to the root of what was causing human beings to be aggressive, they turned to the internal factors — more specifically, what goes into your mouth. They understood that food had the power to harmonize people with their environments.”

The origins of macrobiotics lie not in weight loss but in healing

Proponents and skeptics alike will tell you that macrobiotics is all about lifestyle. The insidiousness of diet culture means that most people are familiar with macrobiotics through its championing of the nutritional superiority of brown rice and its promulgation of the now infamous diet trend of chewing your food to liquid before swallowing. However, the origins of macrobiotics lie not in weight loss but in healing. Drawing from the principles of ancient Chinese philosophy and Zen Buddhism, the macrobiotic diet professes to seek balance through an attunement to the yin and yang properties of edible ingredients and cookware. A student of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ohsawa understood food as an extension of health. Used properly, it could rid the toxins accumulated in our bodies and facilitate the conditions for our body’s natural healing processes. In Ohsawa’s interpretation, the pathway to inner peace began in a disciplined diet that consisted of cereal grains, with grain being the most balanced food, locally sourced vegetables, seaweed and other sea vegetables, as well as beans. Beyond diet, Ohsawa was attempting to design a system of living through macrobiotics that would allow humans to transcend the constraints (and conflicts) of the corporeal.

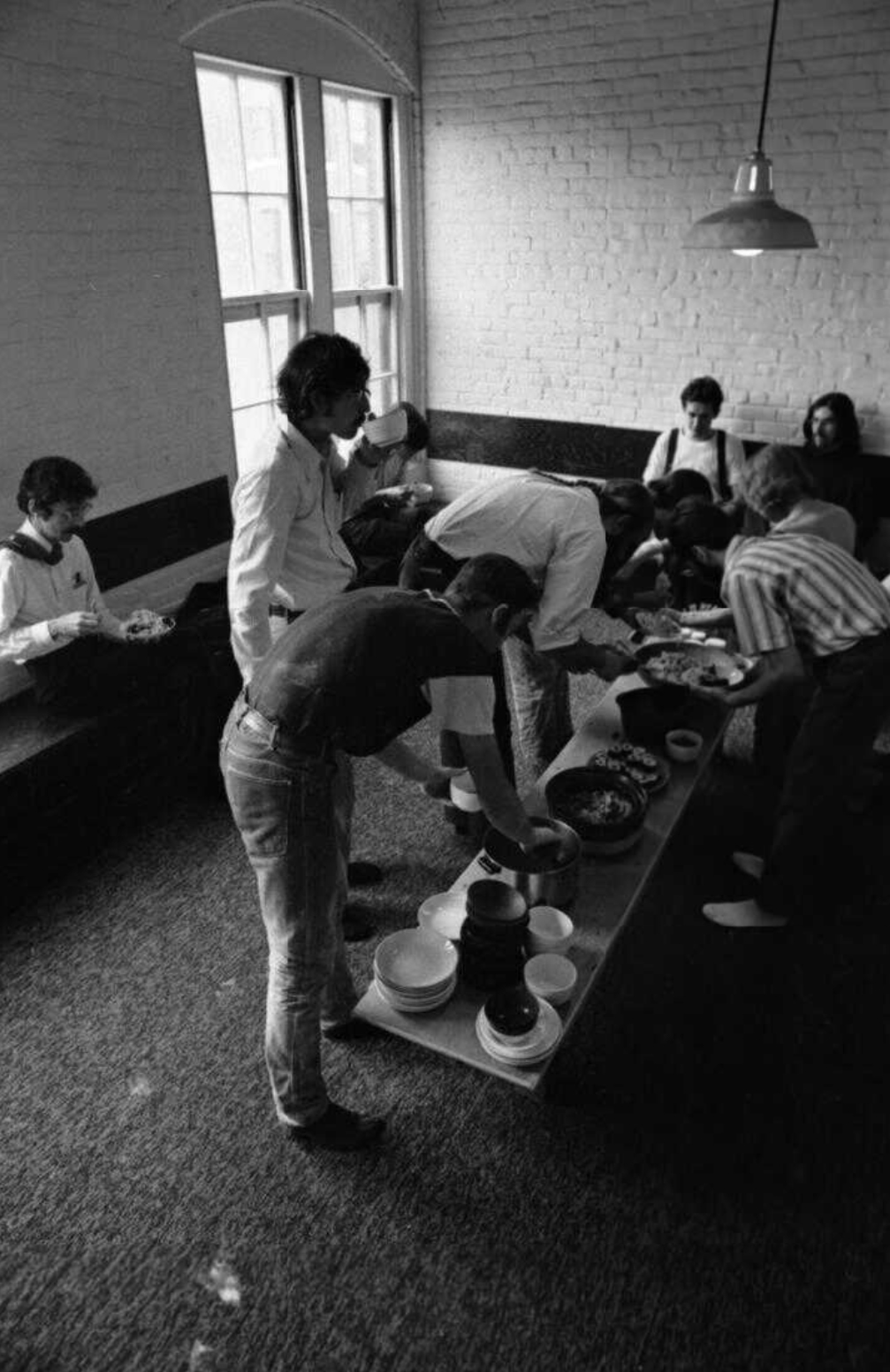

According to Ohsawa and the Kushis, by adopting a macrobiotics lifestyle one could address the root of all illnesses — an improper diet. While these claims were never “scientifically” proven, they argued that an adherence to a macrobiotic diet could cure and alleviate symptoms of illnesses that ranged from the common cold to cancer. This belief manifested in an extensive enterprise that included cookbooks, lectures, publications, workshops, and even a handful of macrobiotic restaurants—beginning in New York City where the Kushis first lived, and later in Boston. To be sure, Erewhon was only one small part of a sprawling machine working toward dietetic enlightenment.

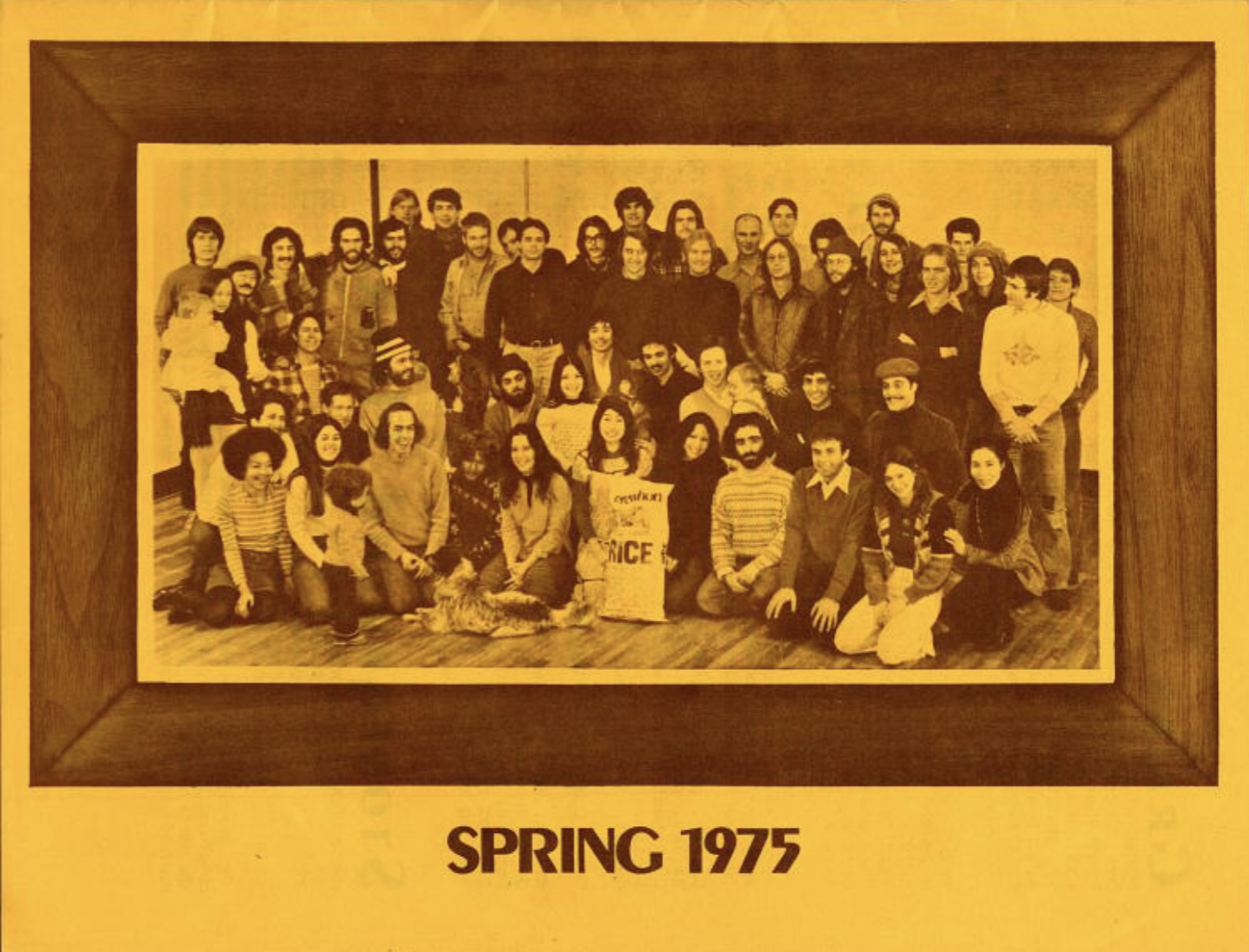

Seeding America’s Organic Movement

In the 1970s, this message of healing captured the imaginations of disciples across the country, who traveled to Boston, then an emerging mecca for macrobiotics, to learn from the Kushis. One pair of roommates from San Francisco, Bill Tara and Paul Hawken, made the pilgrimage after Paul found a book on macrobiotics by George Ohsawa, and allegedly healed his life-long affliction with asthma with its dietary prescriptions. “To be honest, it was probably not macrobiotics, but the ten days where you cut harmful things out of your diet that healed me,” he admits to me in a recent interview. The two, along with a few other members from their theater troupe, settled into the communal “study houses” set up by the Kushis and began working at the small grocery store owned by the couple. The duo would later become the Vice President and President, respectively, of Erewhon Trading Company.

One day while unloading a truck of rolled oats, Hawken noticed something suspicious. The bulk bags the oats were delivered in were labeled National Oat Company Iowa. The problem was, Erewhon wasn’t buying oats from farmers in Iowa, they were supposed to be sourcing from Mennonites in Pennsylvania. Deciding to investigate, Hawken called up the organization to inquire about their organic farming program. On the phone, a woman asked Hawken what organic farming was before patiently eviscerating any notion that the oats had been grown without chemicals or pesticides.

“She told me, ‘Honey, that sounds really nice, but we just buy the oats and roll them.’,” remembers Hawken. At Erewhon, it was important for ingredients not to be tainted by extractive chemical processes. One of macrobiotics’ primary influences was the principle of shin-do fu-ni, or “the body and earth are not two,” which emphasized the relationship between bodily health and environmental health. While Erewhon had been selling the oats under the impression that they were organic (with a premium price tag, nonetheless), the product itself was no different from your average supermarket variety. “That was a real turning point for me,” says Hawken. “I realized the whole natural food business, as it was, up to that point, was corrupt. That’s where Erewhon began.”

Over the next seven years, Hawken would work to expand Erewhon Trading Company’s network of suppliers, contracting 57 farms in 35 states, drawing from over 30,000 acres of organic food to supply not only Erewhon but a network of natural food stores across the country. At the center of these efforts were personal relationships with farmers and a familiarity with the land that was supplying Erewhon’s shelves. “I visited every single farm,” emphasizes Hawken, “I stayed with them, I got to know their kids.”

At this time, natural food purveyors were rapidly expanding off the momentum of Rachel Carson’s 1962 environmental manifesto Silent Spring, which, despite its shaky scientific grounding, had managed to incite a retaliation against DDT worldwide. With this renewed awareness around harmful chemicals and pesticides permeating mainstream consciousness, organic food was no longer just for the hippies and health nuts.

The problem was finding organic foods. As a distributor, Erewhon was carefully stitching together a web from fragmented organic initiatives that had been operating independently across the country. There was a cowboy from the Texas panhandle growing organic wheat and grains — still known today as Arrowhead Mills, there were experimental farms across the South run by the Rodale Institute, the folks associated with what was then Prevention magazine. From the outset, the endeavor seemed like a madcap chase, criss-crossing the country in search of organic farmers. However, according to Tara, there were a lot of farmers already using organic methods, it was only a matter of asking the right questions, “Organic doesn’t have to be complicated, we would just ask ‘Are you spraying chemicals on your wheat?’ stuff like that,” he explained in an interview with MOLD. Tara even notes that some family farmers Erewhon worked with had never sprayed crops or participated in monocropping because of their first-hand experiences with the devastation of the Dust Bowl in the 1930’s. “Whether or not they labeled their practices as organic, they understood what would happen if they didn’t take care of the soil,” he tells me.

Many farmers however, still required convincing. In several instances, Erewhon persuaded farmers to transition their farms to organic practices by offering to pay a lucrative bonus to those who would forgo the use of harmful chemicals. “It was the only card we could play. [Because of our customers,] we could afford to put 10 to 20% more on the bills [than supermarkets],” says Tara. By leveraging a growing consumer base willing to pay higher prices for organically grown foods, natural food wholesalers like Erewhon were instrumental in cultivating the future of organic agriculture within the United States. Eventually, Erewhon would go on to partner with Bay Area natural food pioneer Fred Rohe and a dozen of other retailers, growers, and restaurants to form Organic Merchants (Om for short, of course) to create uniform standards for organic food — what would become the precursor for modern-day organic certification.

Back in Boston, Erewhon was expanding at an astronomical rate. The store had outgrown its claustrophobic basement on Newbury Street and was now operating out of a more spacious location up the block. Inspired by Erewhon’s blueprint, several of the original staff had left for different parts of the country to start their own satellite macrobiotic health food stores. The Boston warehouse continued to serve as a home base for the company, and workers had begun producing Erewhon packaged goods like nut butters and oils on site. When the youngest Kushi child suffered from a particularly bad twisted ankle, Aveline moved out west to California to seek out the healing consultations of a Japanese bone doctor, and in the process, opened Erewhon’s first Los Angeles location on Beverly Boulevard.

The meet-cute is baked into the design of the Erewhon store itself

However, with this new growth came cracks in the booming business’ foundation. The Kushis were more focused on proselytizing macrobiotics through other endeavors, founding the Kushi Institute in Chicago, writing books, and lecturing. The company’s new staff, lacking previous workers’ cult-like devotion to the gospel of macrobiotics, began to criticize the company’s lackadaisical, macrobiotics-centered management style, even moving to form a union in 1979. In her memoir, Aveline: the Life and Dream of the Woman Behind Macrobiotics Today, Aveline Kushi cites the union as one of the contributing factors to Erewhon’s downfall, remarking that unionization was incongruous with macrobiotic’s underlying teachings of gratitude and respect, “The split was too deep… we were saddened.” Despite the influx of business that natural foods’ popularity was bringing, Erewhon could no longer financially sustain operations. By the fall of 1981, Erewhon had filed for bankruptcy and was purchased by a competing natural foods wholesaler.

Nowhere, Today

In some ways, the Erewhon of today is a fluke. Current owners Tony and Josephine Antoci purchased the remaining Beverly Boulevard Erewhon store in 2011 after an initial deal to bring luxury grocers Dean & Deluca to the West Coast failed to pan out. The grocery chain’s ensuing success, however, is no mistake. “Tony and Josephine have a strong design perspective and are very involved with the design process,” says Sean Unsell, associate principal at RDC, the architecture firm behind Erewhon’s now iconic, natural wood-clad spaces. A big part of the grocery store’s allure lies in its ability to facilitate connection amongst its clientele, the idea (not dissimilar to the original teachings of macrobiotics) being that if you are what you eat, and we’re both eating organic roasted almond butter from a mason jar, we must have something in common. The potential to run into a friend, an ex, or even a future soulmate, is what keeps people coming back. According to Terry Todd, another associate principal at RDC, the meet-cute is baked into the design of the Erewhon store itself, “One design aspect that is fairly unique to Erewhon is the height of their shelving and the tightness of their aisles. In big box stores like Aldis and Kroger, the aisles are typically 6 feet wide, at Erewhon they break the rules a little, and have 4-foot wide aisles. This encourages customers to ask for assistance. Erewhon has the highest employee-to-customer ratio of which I am aware, and we had to factor that into the spatial design.” Through design, Erewhon has carefully engineered opportunities for intimacy, emulating the alternative communities of health food stores of the past, in order to build a “community of people who are united in [a] love for pure products that protect the health of people and our planet.”

To see the evolution of health food through the lens of Erewhon is to see an evolution in how we eat. Beyond working to advocate for organic produce, the original Erewhon introduced products like miso and tofu into the Western mainstream market, even becoming the first distributor to import items like seitan in America. Labeled fringe and dismissed for its associations with the New Age in the 1970s, the impact of natural food stores and by extension, macrobiotics, on shaping how we think about eating in relation to the environment, something that has adopted an increased urgency with climate change, is undeniable.

With this knowledge, it is important to understand how the “health food” of today might influence how we eat tomorrow. In a TASTE interview with Erewhon Purchasing Director, Ana Yoon, writer Aliza Abarbel positions Yoon as an arbiter of food trends and a predictor of how people might eat months and even years from today. This is not such a far reach if you consider how ubiquitous items like kombucha and oat milk are on grocery store shelves today. While products like camels milk or deer antler capsules might never gain the same level of popularity, Erewhon’s unique position as a luxury grocery store allows it to incubate products (and the ways of eating they promote) with a consumer base open to experimentation. As Yoon elucidates in the interview, however, price does not really factor into what Erewhon chooses to stock. “What I’m essentially looking to do in the review process is curate the best product, and the best ingredients, for our customers, so they can trust what they see on the shelf. Price is not what triggers us. It’s more about the ingredients, the look, and all that. Pricing tends to be considered at the later stage [in our process] than for some other grocery stores.”

To tie the ideas of community or health to purchasing power presents a slippery slope, one that not only promotes inequality, but also further isolates us from one another. When I ask Hawken, who since leaving Erewhon has become a climate activist, writing books such as Regeneration and Project Drawdown, what he thinks of the new Erewhon he replies, “The Erewhon I helped found has failed. We used to be affordable. The ingredients they still source are incredible and I’m glad that’s still in the DNA. But it’s so expensive, you can’t feed the world that way.” While Erewhon is not necessarily the culprit, it does stand as a symbol of a larger wellness industry that is hampering us from thinking about health from a collective standpoint. Returning to Ohsawa’s original intent to transcend bodily ailments and the frictions of conflict through food, it is important to reevaluate what it is exactly we are trying to transcend. And more importantly, who gets left behind when we do. In the end, wellness, decontextualized from the health of our environment and that of our neighbors and greater communities, is a death drive.