FarmBeats’ 2016 promotional video conjures bucolic, sun-drenched images of small-scale organic farming in the Pacific Northwest: smiling faces, uneven loamy terrain, sunflowers and dirty hands. Scientists are interviewed to describe the high-tech devices scattered across the farm that are tracking moisture in the soil, temperature, and sunlight distribution, drones buzzing overhead looking for patches of nutrient deprivation. Tucked between the weeds of a traditional, organic field are the humming, networked tools of a “digital agriculture solution.”

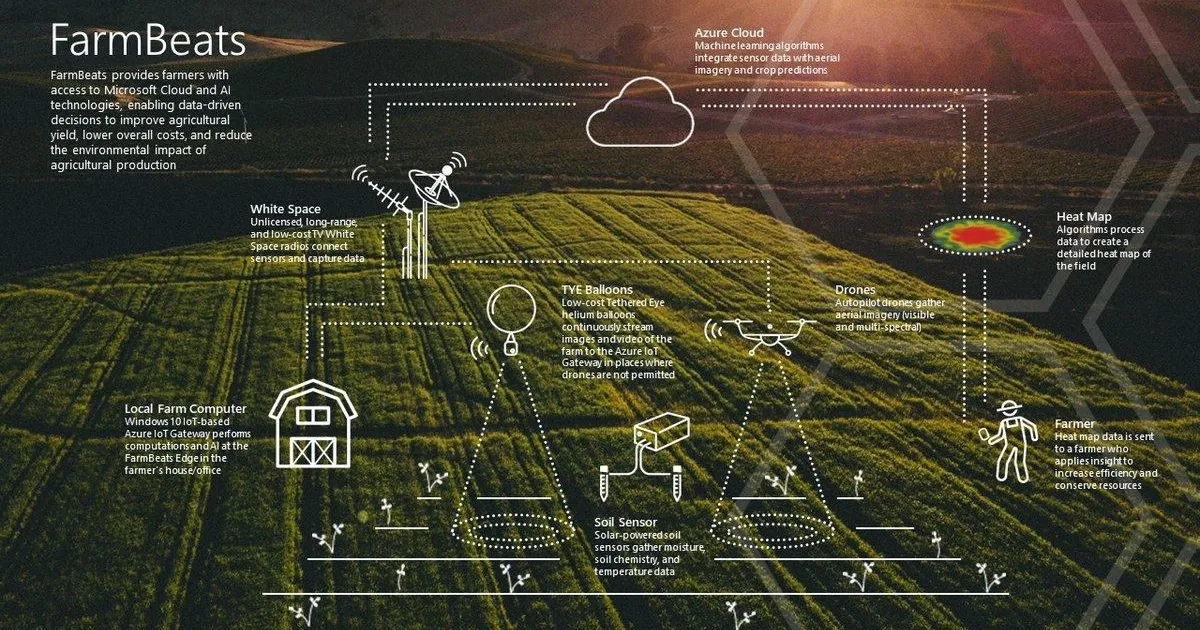

In 2015, Microsoft launched its FarmBeats research project with the aim of optimizing farming in order to meet the looming food crisis of doubling food production by 2050 in order to meet a growing population’s needs. The FarmBeats project gives farmers moisture and chemical sensors, computers, simple routers for internet connectivity and uses drones to take aerial shots, collecting useful data that farmers can use to diagnose problems with. Seven years later, Microsoft has announced that they will be offering the product in Beta mode, as part of their Azure business line. Available for private purchase, it proposes low-cost, simple technologies for smallholder farmers around the world.

FarmBeats is part of a long legacy of agricultural development at Gates-led ventures. Although Bill Gates retired from Microsoft in 2006, he has continued to guide Microsoft’s philanthropic ventures publicly as the company’s legacy director as well as privately as a pre-eminent billionaire philanthropist. These ventures have often coincided with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s interests in techno-utopian health projects. While the foundation is best known for its public health work, they are equally focused on agricultural development. While the Foundation’s development strategy is multifaceted, the interim agricultural director of the Gates Foundation, Dr. Enock Chikava, has emphasized in a statement written in advance of COP 26, that decision-makers should “expand access to seeds, agricultural financing, digital tools, and information that farmers can use to improve their yields” for smallholder farmers threatened by climate change in order to bringing them into a global market and offering technological solutions.

Recent reports detailing the extent of Gates’s land ownership have prompted criticism from some environmental advocates, who suggest a contradiction between his public environmental advocacy and his own personal investment strategy. FarmBeats proposes a network of low-cost sensors, collecting aggregated datasets to give farmers “actionable insights” and “track farm conditions by visualizing ground data.” Through the project, FarmBeats intends to create a single B2B product that enables growers to build artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning (ML) models for smallholder farmers across the world, promising to “democratize agriculture intelligence.” But what kind of intelligence is it democratizing?

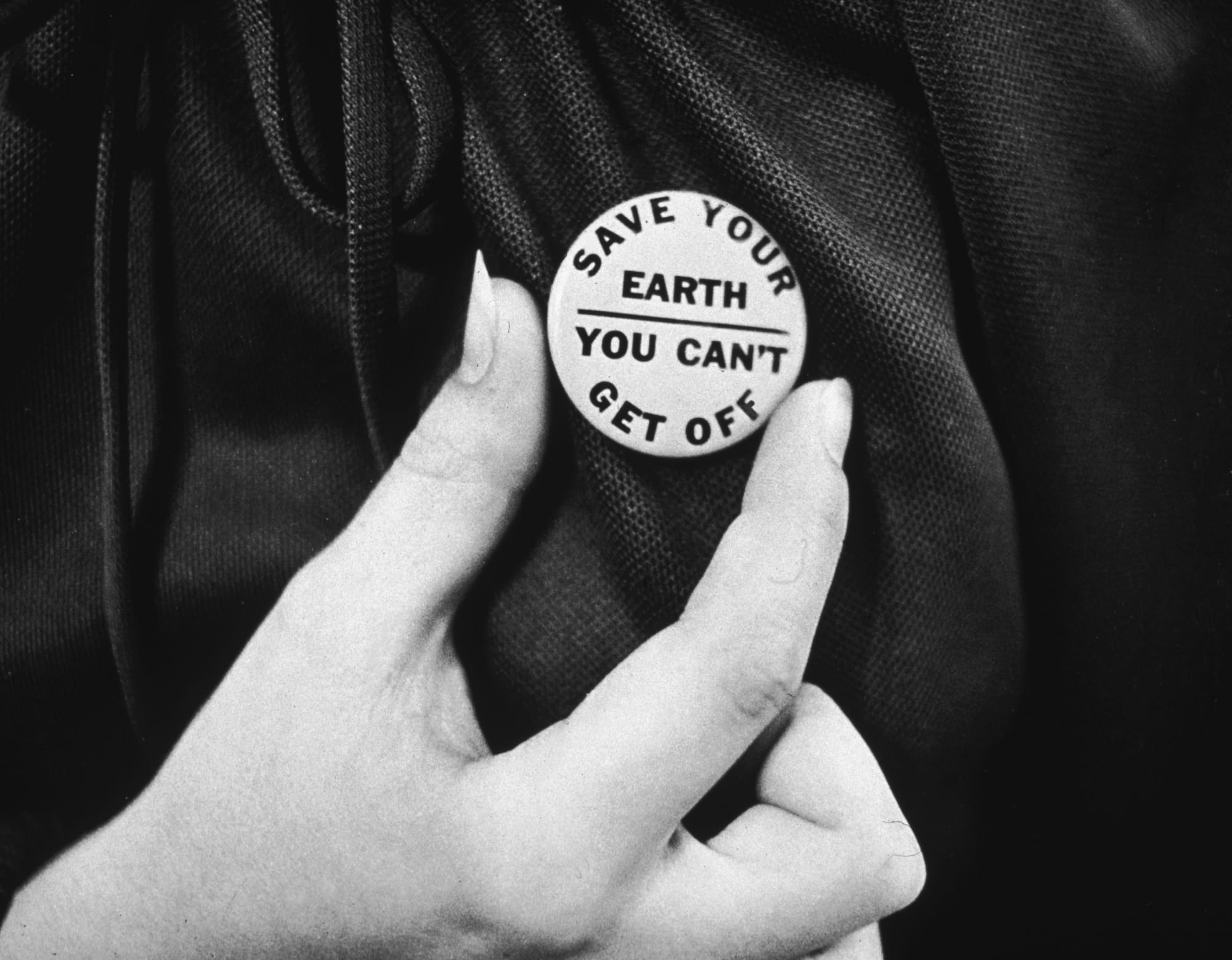

High-tech sensors, specifically those that track water may be especially valuable in areas prone to drought. But many of the innovations that define today’s concept of ‘agriculture intelligence,’ (chemical fertilizers, industrial machinery, monoculture crops and the technology that accompanied the Green Revolution), have not aged well. Gains in agricultural productivity have come at a huge cost to both environmental and human health: pesticides destroy ecosystems, genetically modified seeds don’t adapt well to adverse weather, patented seeds are engineered to be sterile, fertilizers contaminate water, glyphosates disrupt endocrine systems, and heavy machinery erodes topsoil. Yet, in a promotional GatesNote video titled “The Future of Farming,” Bill Gates declares the Green Revolution a success—and reasons we should do it again “to help the poor move to a more prosperous life.” Describing the era’s technological advancements and economic growth, Gates concludes, “now we need to bring that advance to Africa.”

In a 2018 TEDTalk about FarmBeat’s technology, Microsoft scientist Ranveer Chandra who has led the project since 2016 affirmed that the goal of the project is to “bring down the cost of data-driven agriculture solutions” and to “bring technology to smallholder farmers everywhere in the world.” It’s a philanthropic, but ultimately private, enterprise, focused on incorporating smallholder farmers into the globalized economy and modernizing the traditional knowledge that’s long defined their work.

FarmBeats promises to outsource a trove of data off to partnering research labs that have “the expertise to diagnose problems.” In this scenario, a scientist 4,000 miles away can theoretically diagnose a Phosphorus deficiency. But would the farmer on the ground be able to reach that conclusion, touching the plant and assessing its needs? Could the smallholder farmer simply replenish their soli’s nutrients and microbiome with compost instead of mining phosphate rock? Technological advancement increases our reliance on technology.

Traditional agricultural methods measure water tables with shallow wells, boreholes, and track moisture levels in the soil by seeing, or touching the ground, heightening an intimacy with the earth unmediated by quantitative ‘solutions.’ Traditional, small-scale agriculture tends to be far more autonomous and self-reliant—it necessitates a smaller-scale operation, cultivates intuition, relies on integrated pest management strategies, and prioritizes native plants. Despite their challenges, these methods still manage to help smallholder farmers feed one third of the world.

FarmBeats’s greatest proposal is to help smallholder farmers use water efficiently, reducing water stress in places where desertification and heat stress will demand it (if they don’t already)—but the future of farming will need to be regenerative and restorative to be sustainable. Moisture sensors and drone photos might contribute to this collective strategy, but living in the shadow of the chemical and mechanized Green Revolution, it’s only natural to be wary of a digital one.