COVID-19 has created a very visible shock to supply chains globally. The Urban Design Collective, a collaborative platform for participatory planning to create livable cities, took the opportunity of the lockdown across India to understand who actually feeds their city, Chennai, currently, and how the solutions created by the disruption of these supply chains may continue post-COVID. More importantly, their work focused on what we can learn from such scenarios and how building food smart cities, where public and private actors can focus on creating a sustainable urban food system that enables social inclusion and access to safe and nutritious food, engenders more resilient urban spaces.

We spoke with Founder and Principal, Vidhya Mohankumar, and associates, Srivardhan Rajalingam and Nawin Saravanan to learn more about their mapping and research for “Who Feeds Chennai?” and their vision for how to build food smart cities in India by the year 2025.

Elizabeth Yorke: You first looked at food supply before COVID-19. Tell us about what you mapped and how that has changed over the last two months?

UDC: First, food coming into Chennai comes from not only different states across India but also from different districts within the state. For example, our tomatoes come from Mulbagal, then we have grapes that come from Hyderabad, coconut coming from Pollachi, and then turmeric from Erode.

Before COVID, most of the produce came to the wholesale market Koyambedu, one of Asia’s largest perishable goods markets and currently a COVID hotspot. From this market, there are a significant volume of people who buy retail, but the majority are wholesale buyers, shops, hotels, communities, temples.

The Koyambedu market is where most retailers from Chennai and also the neighboring districts pick up their produce for sale. It’s a very centralized operation barring a few franchise-based stores that have their own direct ties with farmers who supply to them exclusively. In the COVID situation, except for bulk consumers who were not operational most small retailers were still allowed to access the market for purchasing produce. Until it became a COVID hotspot and the city had to shut it down eventually.

During the lockdown, we are seeing more stores and shops signing up with delivery platforms, like Swiggy and Zomato. There have also been some services that deliver directly to consumers’ homes from the markets. The Tamil Nadu Horticulture Department Agency opened a portal, ethottam.com, for delivery of vegetables and fruits. The Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) also organizes special vehicles that carry produce to families/communities at the neighborhood level. In containment zones, there are mobile vehicles with supplies and GCC is engaging with volunteers within these zones to help distribute supplies.

Government food distribution initiatives in Chennai

Government food distribution initiatives in Chennai

Private Sector food distribution networks in Chennai

Private Sector food distribution networks in Chennai

EY: Did any of this surprise you—that the food coming into Chennai travelled into the city from so far away?

UDC: Food is coming from outside the city—and that is a default. The city has been growing horizontally. We’ve been eating up all the farms that were originally part of the hinterland. And a large part of the population has been buying properties in the peri-urban belt because that’s where it’s comparatively affordable.

The idea that your food can come in a truck from somewhere else and somebody else will grow your food for you, is so ingrained in us. As an extension, we’re also seeing a lot of imported food right now in the market because more and more people are now exploring different world cuisines. If you actually do go to the market, nobody is even able to recognize the foods that are grown locally, the foods in season, and the ones that come in packaged with a large carbon footprint. Watermelons are available throughout the year, and nobody thinks that is strange. We see mangoes in December and no one blinks an eye. As long as the options are there and the options are growing, people seem to be content with the system the way it is.

EY: How do you think COVID-19 has impacted the way people are thinking about the food system?

COVID-19 should be seen as an urgent call for action more than anything else. This whole idea of the megalopolis and the over-dependency on faraway lands to satisfy our basic needs is not sustainable anymore. COVID or not, it’s just not sustainable.

I read an article last week about Bhutan and how they were in a similar situation because much of their produce is imported from India. Since the borders have shut down, they’re being forced to grow their own food. The government is encouraging, subsidizing and incentivizing people to start farming within the country. In other words, they are seeing this disruption as a blessing in disguise. For decades, they have tried in vain to be self-sufficient and reduce their food imports, until now.

EY: How have you envisioned Chennai being a smart food city by 2025?

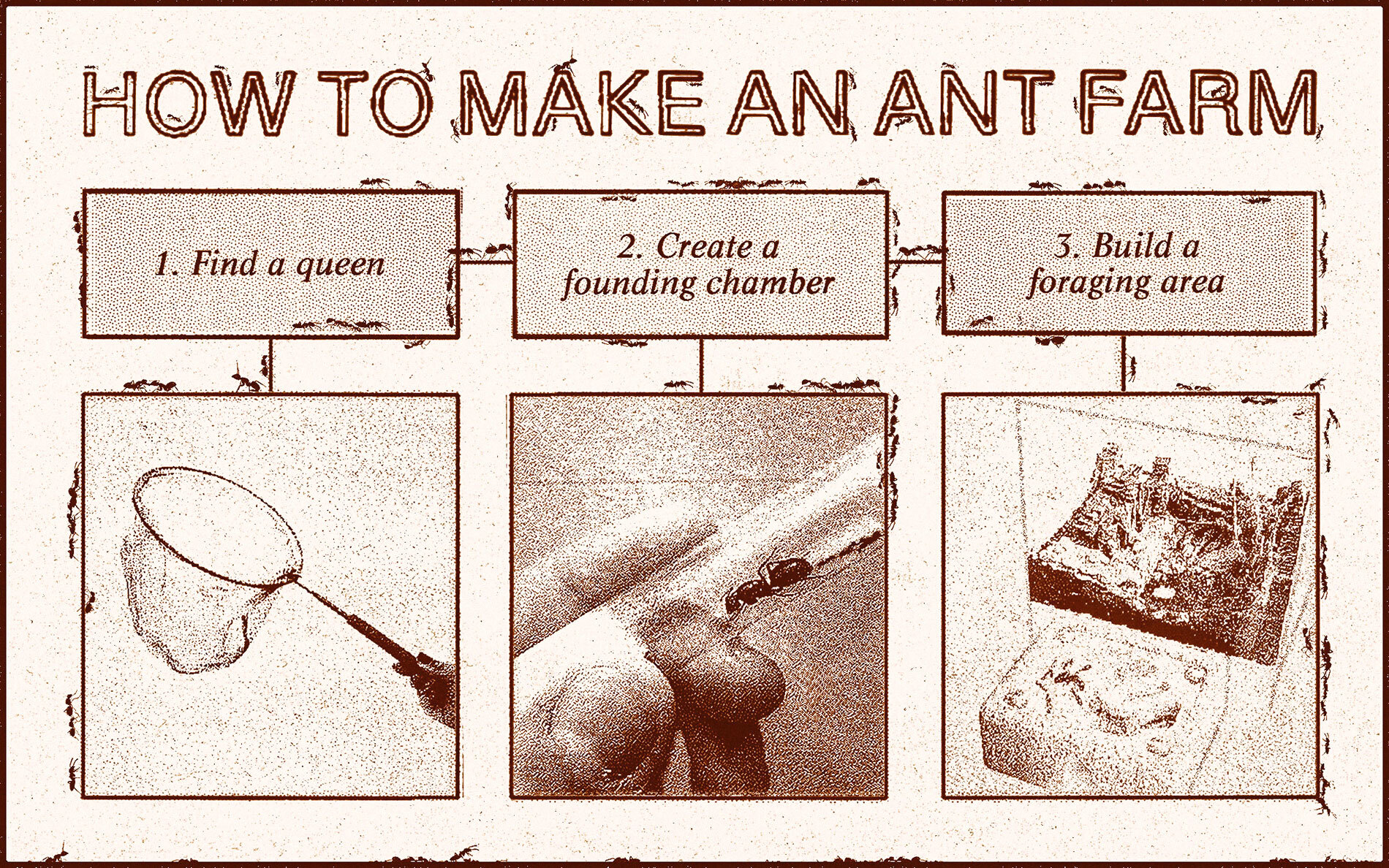

UDC: More than ever, we need to build something better, together, so as to not be in this same situation again. So we explored the idea of converting the city’s unused/ residual parcels of land into community thottams (thottam is a Tamil word for farm) and showing possibilities for different stakeholders—individuals, apartments, gated communities, even public buildings and educational institutions—to produce food. As an extension of this idea, we also wanted to capture the many terraces of buildings as mottamadi thottams, (mottamadi meaning rooftop terrace) for the same purpose.

EY: But would these urban thottams be enough to feed the city?

As you see in our graphic (below) a major supply chain that is being fractured because of the pandemic is bulk supply—there are no weddings/ caterers, no hotels/restaurants open, no religious activities. According to a study we found, almost 60-70% of produce goes into the bulk supply chain. Right now in urban areas, there is only an individual household requirement for produce.

Produce and people coming into the city from outside and going back has clearly been detrimental at a time like this as seen at the Koyambedu market and how it has come to be responsible for escalating COVID case number not just in Chennai but in neighboring districts and states. If we can produce 10-15% of our food within the city, we would be able to meet the city’s needs in circumstances like this.

Another common statistic is that ⅓ of the world’s food produce is wasted. One reason for this is the long supply chains and lack of adequate storage facilities. Much of this could be prevented if vacant land parcels in our cities could be used productively to share this demand.

This could also become a livelihood opportunity for people who want to move out of villages and into the city i.e. we could lease out such spaces to seasoned farmers to grow food while also getting the benefits of urban life. Not everybody would be interested to engage in farming activity but by presenting the option of leasing out spaces, it can still remain a viable solution. Adding rainwater harvesting techniques and organic waste composting as ways to sustain the thottams financially will also make this an experiment towards a circular economy. And of course, we ourselves, together as a community, would have access to healthy food that is grown locally!