The ancient combination of flour and water, or flour and eggs, has become something of a staple food in countries across the globe. Although pasta as we know it has records dating back to the 13th or 14th century, evidence of similar dough-based food has been found in ancient civilizations, from Asia to Europe. Pasta’s popularity throughout history is almost certainly due to its simplicity — in both composition and flavor — and versatility. As written by Silvano Serventi and Françoise Sabban in Pasta: The story of a universal food, “Simple and neutral, it places no restrictions on the search for new combinations of textures and flavors.”1

From hand-pulled noodles from China, to lagana (a kind of pastry dough) popular in Ancient Greek and Roman cuisine, the history of pasta is ubiquitous, and depicts the culinary innovation and creativity of civilizations all over the world that have existed for thousands of years.

From testaroli to Pasta di Gragnano

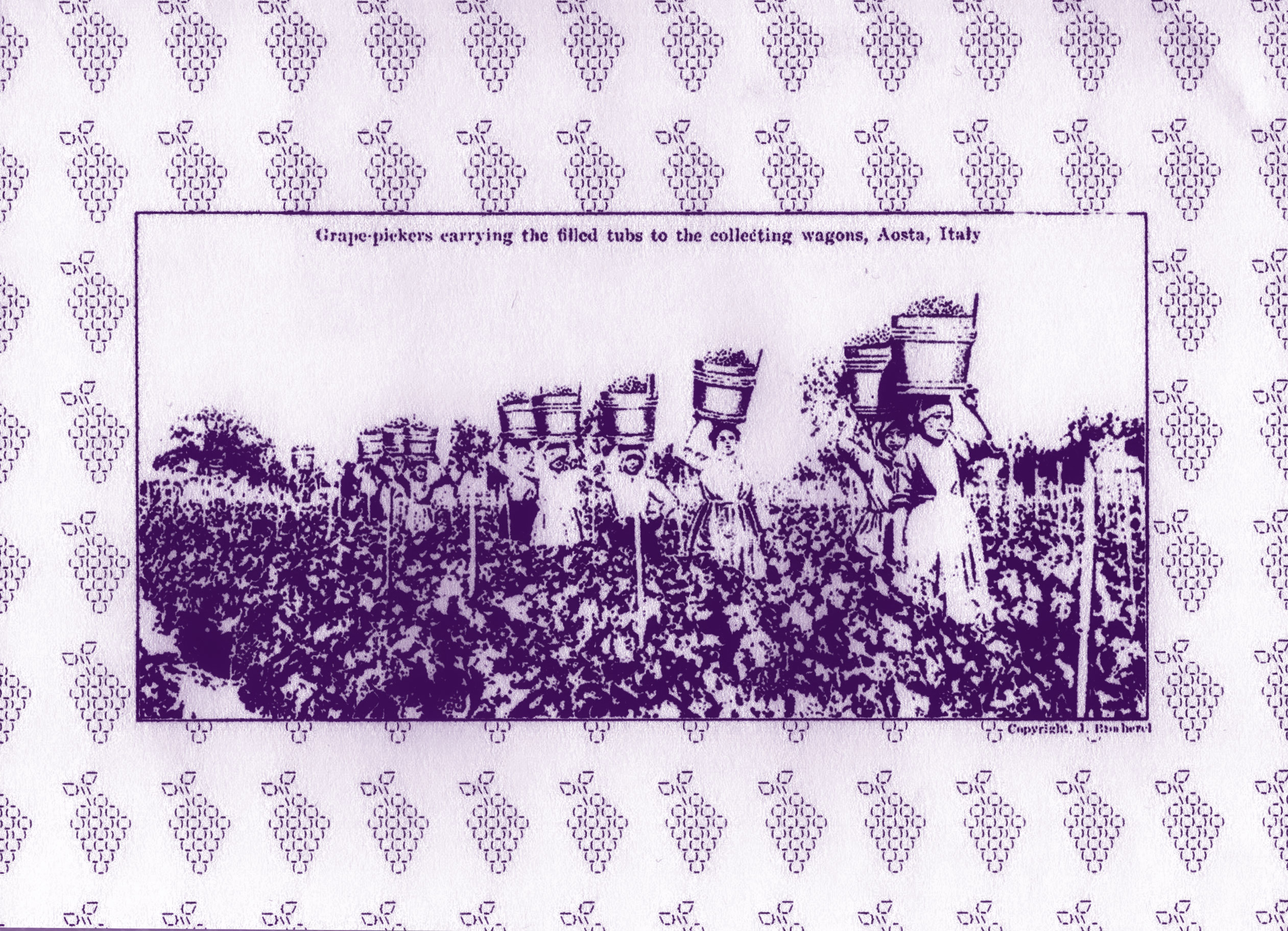

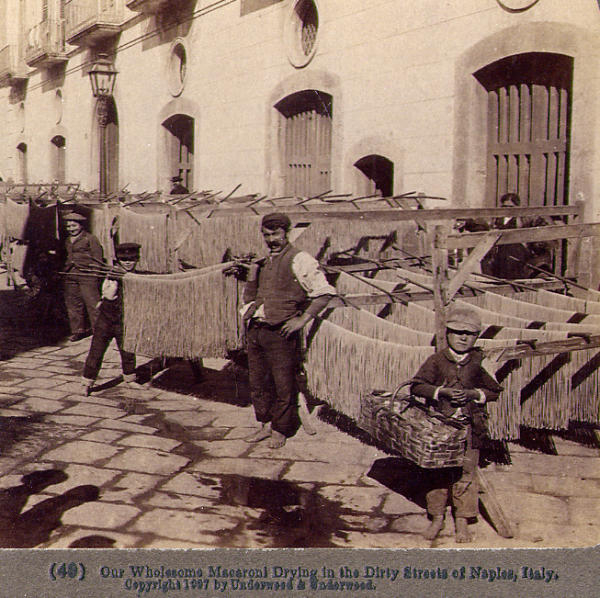

Although variations of the dish have been consumed across the world essentially since we’ve had the knowledge and tools to grind flour, Italy has established its position as the home of pasta. With the country’s Mediterranean climate making it the ideal environment for drying pasta, by the Industrial Age, the cities of Genoa and Naples had become the centers of manufacturing and export. Neapolitans were even known as mangiamaccheroni (“macaroni-eaters”) due to the reliance of the working class on pasta, which was served by street vendors onto plates, to be eaten with bare hands. Pasta made in Gragnano, a town southeast of Naples, has been awarded PGI status (Protected Geographical Indication) by the European Union, due to its history of producing pasta with its local water, and drying it outside in the sea breeze.2

- 2. L. Hengel, “Why Pasta Di Gragnano is the Best in the World”, Forbes, April 30, 2019.

As described by Serventi and Sabban (2002), the innovations of pasta-making in Italy “contributed to the development of a genuine technical, cultural, and gastronomic heritage” for the country.3 But Italy’s pasta traditions begin long before the product started being manufactured for the masses, and even before the term ‘pasta’ was being used to collectively define this food. At least one form of ancient pasta still holds a place in contemporary Italian cuisine today. Testaroli, which has been named “the earliest recorded pasta”, originates from the Etruscan civilization which spanned from 900 BC to 27 BC.4 Its name comes not from its shape as with many later forms of pasta, but from the testo it is cooked upon – a flat terracotta or cast iron pan. Sometimes referred to as a bread or crêpe, its only ingredients are flour, water and salt, cut into triangular shapes after cooking. Testaroli remains a specialty dish in the region of Lunigiana, now often served with pesto or simply olive oil and cheese.

“There’s nothing like real, home-grown spaghetti”

So how did macaroni, spaghetti and penne make their way into English cookbooks and saucepans? Waves of migration from Italy in the late 19th and 20th centuries caused pasta to infiltrate the cuisines of America and the United Kingdom.5 Pasta dishes soon gained popularity, due to the dried product’s ease to transport, store and cook.

IFST (Institute of Food Science and Technology)“Pasta is a low cost, [versatile], nutritious food that can be consumed globally on an every-day basis by many populations.”

The public’s quick embrace of the food, however, meant that many consumers were unaware of the rich history and tradition of pasta-making – or even what it was or where it came from. In what is now known as the ‘spaghetti-tree hoax’, an April Fools Day broadcast by the BBC in 1957 displayed a family in Switzerland harvesting a crop of pasta from their ‘spaghetti tree’. The broadcast on BBC Panorama resulted in hundreds of confused callers, some asking for advice on how to grow their own.

Pasta: A past and future food

Thankfully, public knowledge around pasta’s origins have expanded since the spaghetti hoax of the ‘50s. Pasta’s effortless allure has made it a staple foodstuff in many countries’ diets around the world, due to its simplicity, affordability and versatility.

Despite the dish’s centuries-old traditions, recent innovations in pasta have looked to address changing consumer needs, from nutritional benefits and dietary requirements, to sustainable sourcing and production. Just this year, Institute of Food Science and Technology have released an open call for papers for a “Special Issue on Innovations in Pasta Production to Improve Sustainability, Nutrition and Quality”, aiming to investigate experimentations in “formulations and ingredients, nutritional impact, tailored processing and sustainability aspects”.

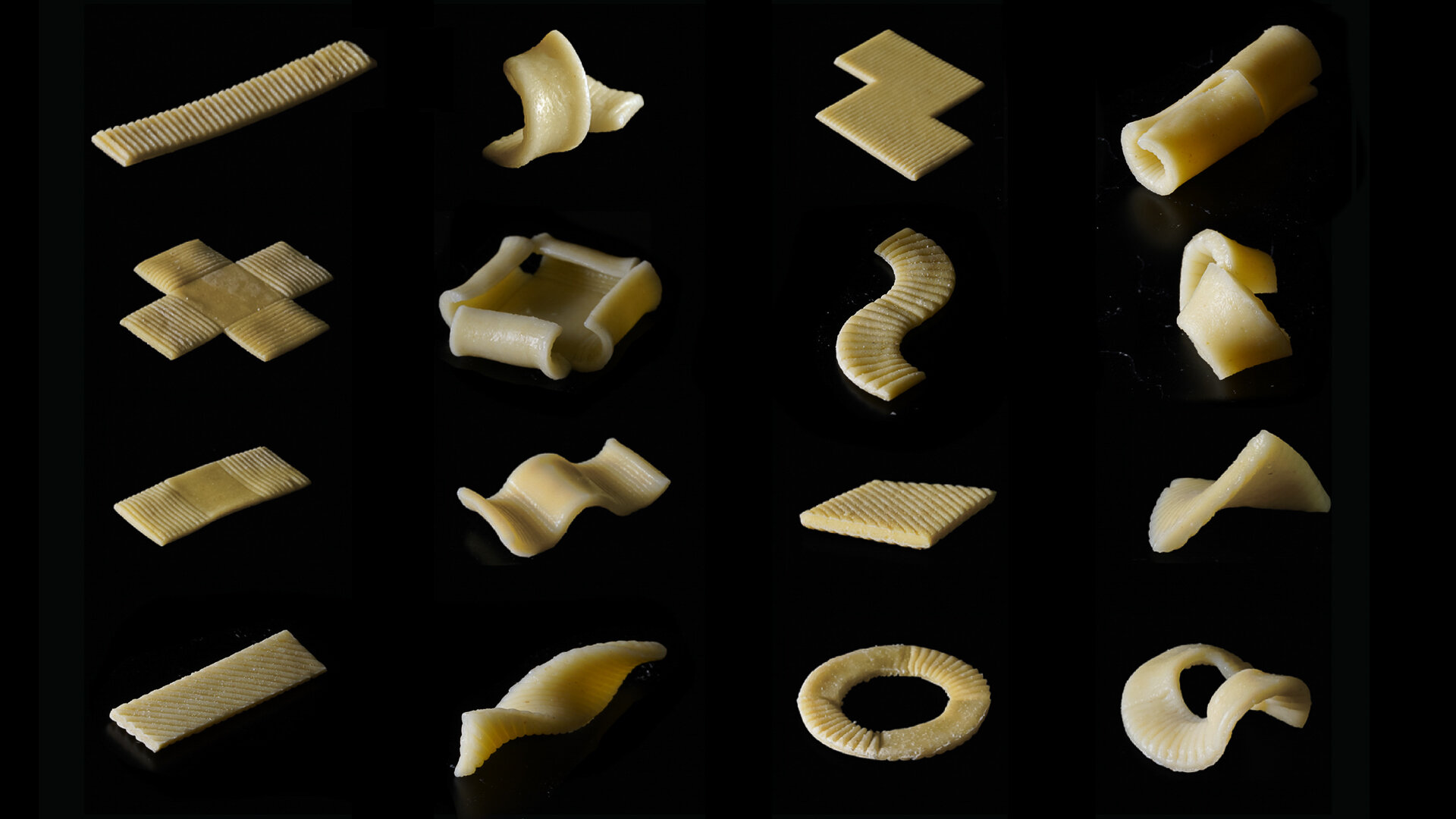

Morphing Matter Lab, of the Human-Computer Interaction Institute, School of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University is looking to re-invent the design of “morphing matter”. Their project “Morphing Pasta and Beyond” investigates the concept of “flat-packed” pasta to reduce packaging, and transform transportation and storage. Inspired by flat-packed furniture and its ability to save space and reduce carbon footprint during transport, the Lab explored the addition of parametric surface grooves to pasta dough through a stamping process, which “can transform flat objects into designed, three-dimensional shapes”.6

Morphing Matter Lab, Carnegie Mellon University“Nearly all food morphs during the cooking process. For example, pasta expands and softens as it is boiled due to water diffusion, the relaxation of the macromolecular matrix, and starch gelatinization. Such morphing effects, if engineered properly, could positively impact the food industry, chefs, consumers and the environment.”

The engineering of flat-packed pasta could also see a reduction in the carbon footprint of the actual process of cooking pasta. As stated by Morphing Matter, flat pasta shapes’ surface area to volume ratio means it cooks quicker than pasta with an inner cavity such as macaroni.

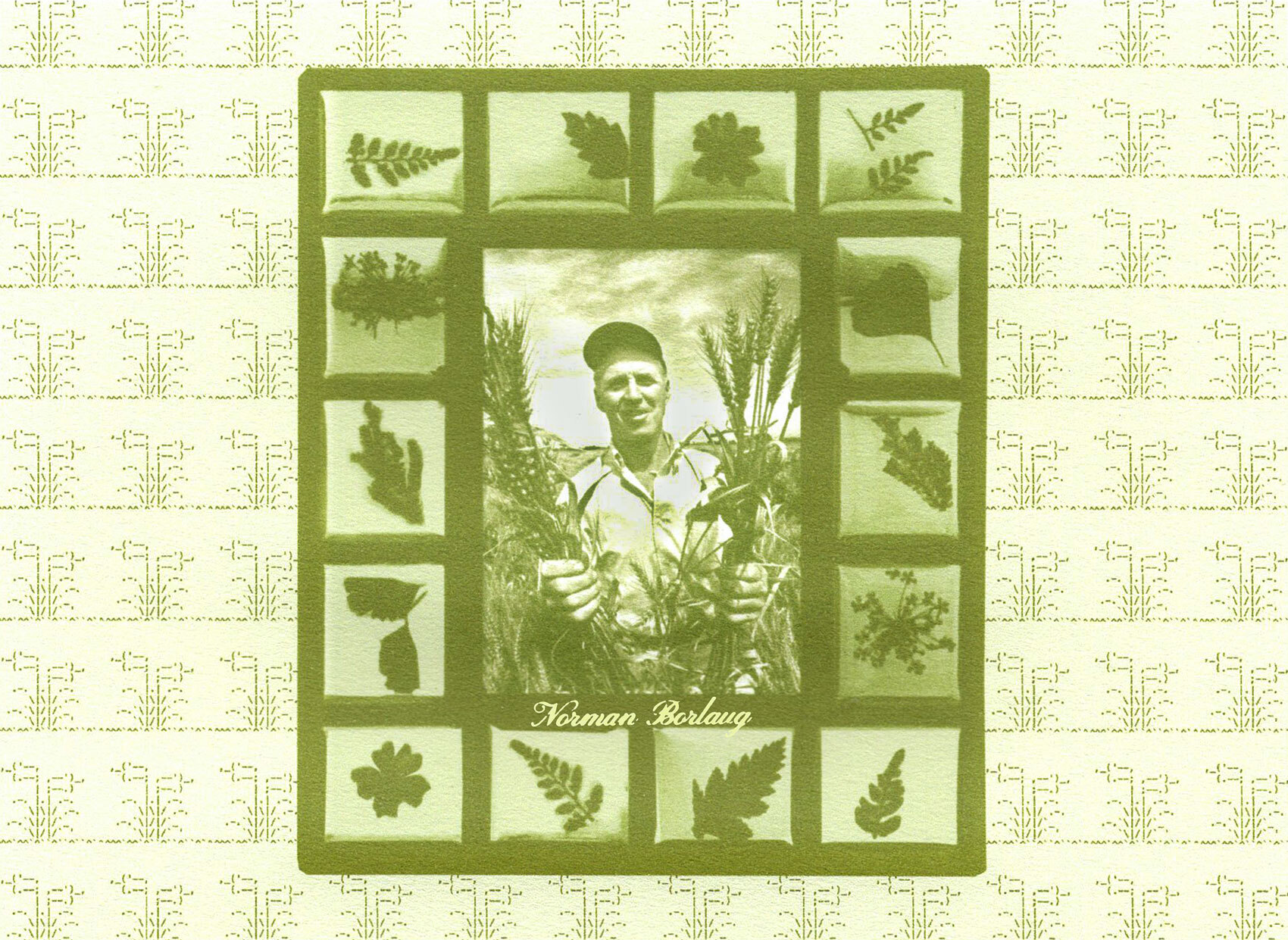

Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, changing attitudes and awareness to the sourcing of ingredients is changing the way bread and pasta are produced. London-based brand Wildfarmed produces flour that prioritizes soil health, by working with regenerative growers in both the UK and France. Varieties of wheat are grown using regenerative methods that encourage plant diversity and maintain yields “within nature’s limits”.

Wildfarmed“We are creating a traceable field to plate network which allows consumers to participate in the restoration of soil and biodiversity.”

It would take thousands more words to truly boil down the ancient history of this fundamental food, but its omnipresence in cultures across the world from China to the Middle East, to Eastern and Western Europe, proves that the simple marrying of flour and water has been sustaining humans for centuries, and in some cases, millennia.

As we look to build adaptability and resilience in the diets of the future, does the answer lie in these two basic elements – wheat and water – and the agricultural, culinary and creative possibilities that they hold?