Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

In The Way We Eat Now, British food writer Bee Wilson examines the rapid changes in how we source and eat our food, citing the growth of convenience food, fast food outlets and food trends for homogenising our diets all while promising to make our lives easier. Our attitudes towards eating in our fast-paced lifestyles are constantly evolving as we are targeted by the next product or solution that promises flavour and satisfaction for less money, less time and less effort. For some, eating has even become a chore, an act carried out while standing over the kitchen counter, walking to work or sitting on a train. This phenomenon, which Wilson calls a “nutrition transition”, has been gathering speed since the aftermath of the Second World War, as governments scrambled to recover from the resulting scarcity. As Wilson writes, “We are still living with this legacy of quantity over quality.

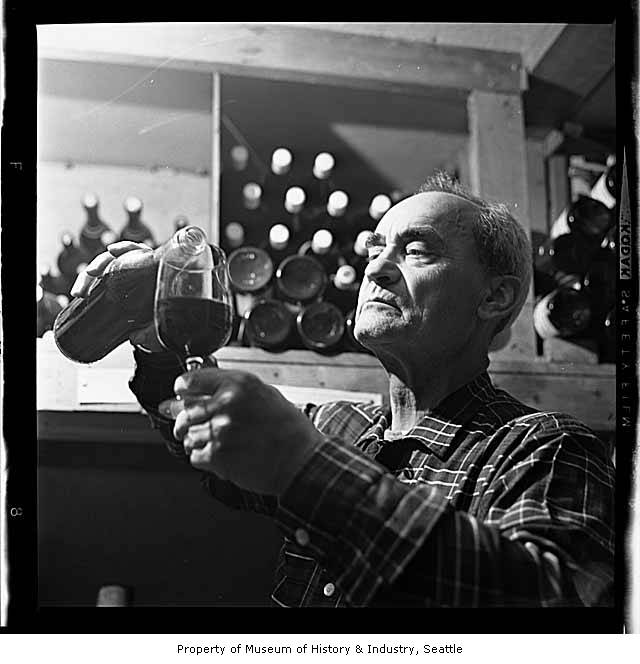

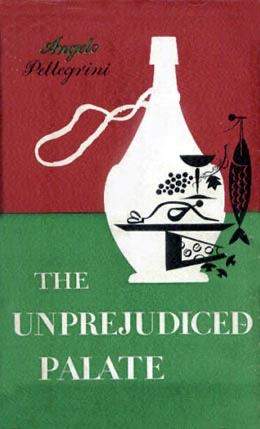

Author Angelo Pellegrini immigrated to America from Tuscany as a 10 year old (University of Washington Magazine) in 1913, and witnessed fast food culture take hold of the USA. A pioneer of the slow food movement (even before John Seymour’s self-sufficiency manifesto), Pellegrini wrote of the importance of growing your own food, home cooking, and taking life slowly—just as he had grown up living. Writer Ruth Reichl describes Pellegrini’s first book as not just a cookbook, but “a manifesto for living the good life,” a philosophy he introduced to America, writing several books throughout his lifetime on ‘the good life’ and the immigrant experience.

Soil to Table

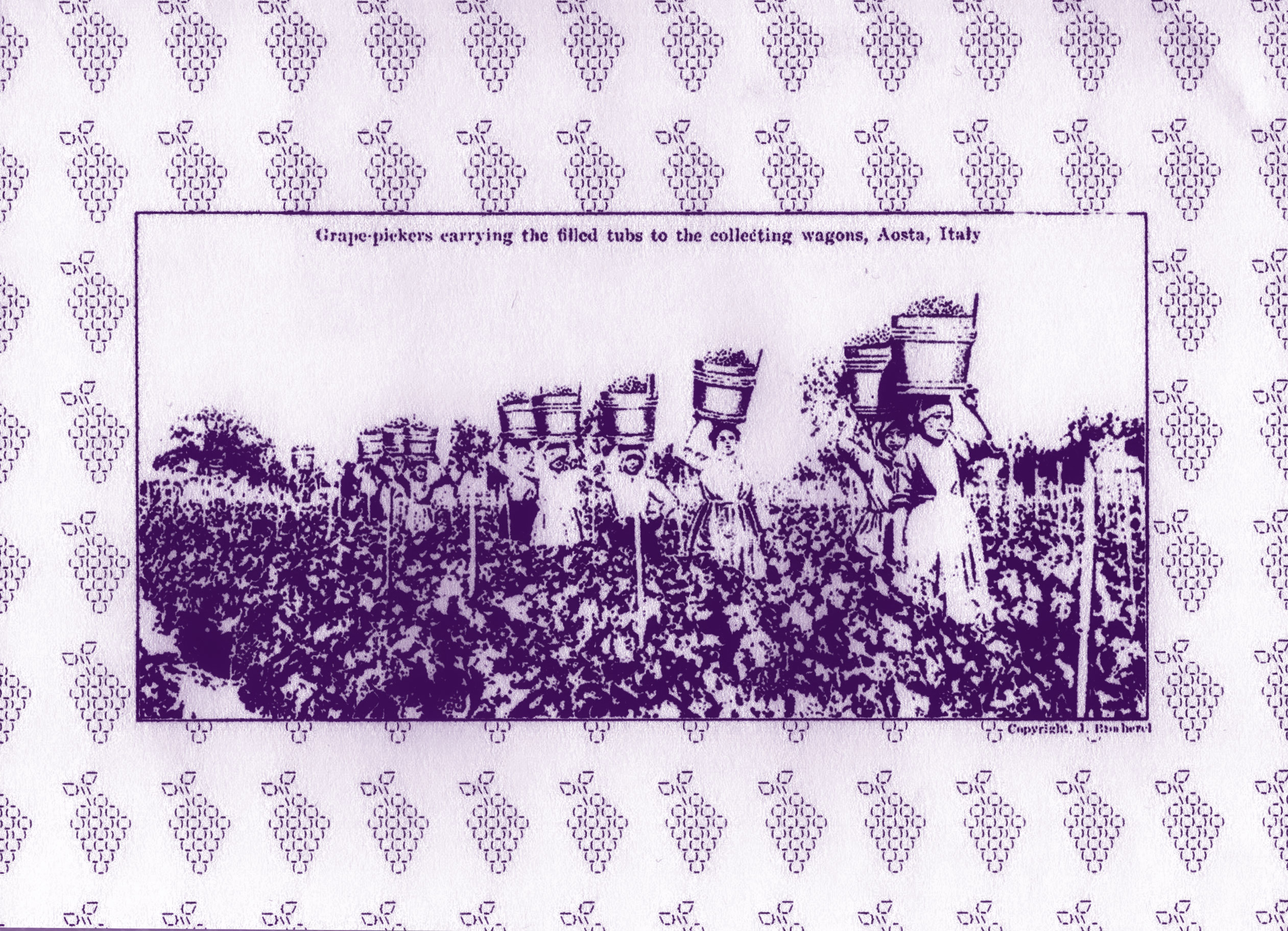

Pellegrini’s philosophy of a “soil to table” lifestyle echoes throughout The Unprejudiced Palate, undoubtedly tracing back to his early childhood in Italy. The 1948 classic, which has gained a cult following in the food writing world, serves as a guide to resourcefulness, seasonality and simplicity. In it, Pellegrini recalls his peasant roots in Italy—selling manure with his father, assisting at wine making and helping on the land—his writing lacing a heavy emphasis on the importance of fresh and simple food and the environment it has come from.

“I do not mean, certainly, that we should worship carrots and make a ritual of bread and wine,” Pellegrini jokes, but adds “The wheat fields and the forests, the orchards and the vineyards, directly or indirectly—these put food in our stomachs and clothes on our backs.” What he was asking America to understand was that the abundance available to us needs to be respected and cared for, if not for the sake of the land then for the sake of our own wellbeing.

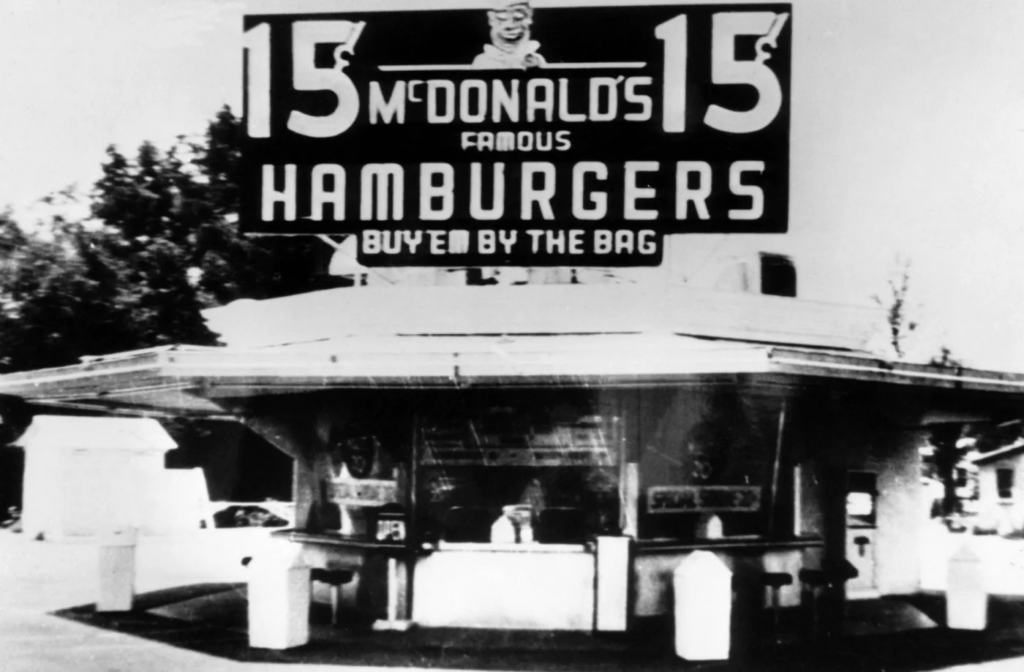

Reichl, who hailed Pellegrini as a “slow-food voice in a fast-food nation” (Seattle Weekly), noted his decision to rip out his Seattle lawn and replace it with a wild garden in which to grow his own food—an act that likely shocked his American neighbours living amongst the opening of the first McDonald’s (in 1940) and other fast food inventions for an increasingly impatient and convenience-hungry population.

The Unprejudiced Palate, which introduced the American reader to basic agricultural principles and home wine-making practices based upon Pellegrini’s Italian lifestyle, also describes, in prose, a series of recipes and suggestions for those “genuinely interested in culinary self-development”. Covering everything from the correct way to cook fresh vegetables — directly in a stock or condiment (“water, no matter how good and cool and sparkling, has a rigidly limited culinary value”) — and how to shop for meat (“the best approach is to compliment [the butcher] generally on his fine shop”) to staple kitchen ingredients and a lengthy glossary of pasta varieties, Pellegrini advises the reader on each act of seasoning, cooking and eating. He may playfully mock the American cuisine throughout, but notes that the country’s own agricultural abundance opens the door to such culinary possibilities.

The roots of a global movement

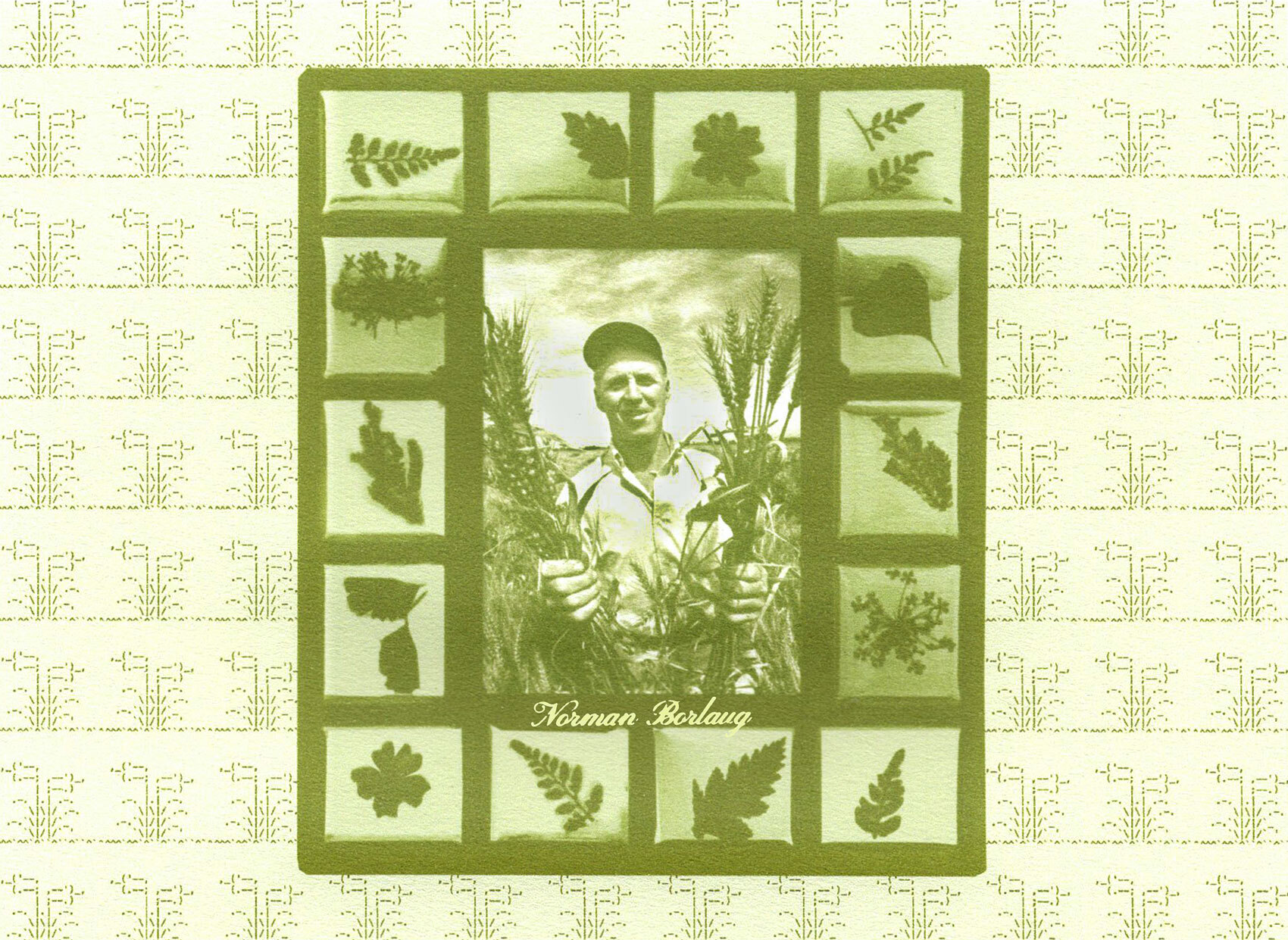

While Pellegrini’s distinct message transformed how many approached food in America, his calls for a slower lifestyle and a return to the soil also resonated in his home country of Italy. In 1986, just a few years before Angelo Pellegrini’s death, the Slow Food Movement began to take hold after food activists led a demonstration on the intended site of a McDonald’s in Rome. Founded by Carlo Petrini, the movement’s Slow Food Manifesto calls for an escape from the ‘fast life’, advocating for food history and traditions. In the manifesto Petrini proposes that a return to slowness is also a return to pleasure, writing “let us rediscover the rich varieties and aromas of local cuisines.” The movement now has a global network of communities and producers working to establish good, fair food around the world. Born of the natural Italian connection to the land and food, the movement works to catalogue endangered traditional foods through the Ark of Taste, a list of heritage foods now at risk of no longer being produced or eaten; create a network of international farmers’ markets; and increase food education with the launch of the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo.

In Pellegrini’s final chapter of The Unprejudiced Palate, titled ‘Toward Humane Living’, he acknowledges the complexity of his suggestions for the Good Life, and the abundance found in America that is not available elsewhere:

“Before the conditions to human welfare become equally accessible to all, there are persistent problems in politics, economics, and social relationships which must be solved by intelligent, collective action…

…Where the conditions to his well-being are contingent, he must act as a citizen; but where they are purely a matter of his own will and initiative, he must bestir himself as an individual.”

It is this philosophy to be responsible for one’s own lifestyle, taste and happiness — while considering its impact on the environment and others — that set Pellegrini apart and revolutionised cooking and eating in America, and work that the Slow Food Movement has continued and built upon for the future.