Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

The resurgence of holistic healing and natural medicine in the 21st century world shows no signs of slowing down. Its growing popularity is, perhaps, a result of the modern “self-care” movement, or the innate urge to reconnect with nature in the face of climate change, not to mention two years battling a pandemic. Holistic healing practises go back thousands of years to Chinese, European and indigenous American medicine, but contemporary Western societies have since commodified these beliefs of herbalism and home remedies for wellbeing, leaving many without the knowledge of these communities’ rich histories.

Increasing concerns about our modern food production, diet-related illnesses and the damages we are doing to our bodies as well as our planet have only helped our trust in natural solutions take root. While some may remain skeptical, many of these natural solutions can often be found already in our own cabinets. Whether it’s herbal treatments like St John’s Wort for anxiety and depression, pop echinacea capsules to fend off the common cold, or our favourite herbal teas to unwind before bed or settle our stomachs, natural remedies are often already an established part of our everyday routines. In skincare and beauty, essential oils and medicinal plant properties have become highly sought after, with pipettes of rosehip or tea tree oil promising to erase blemishes or slow signs of ageing. This hunger for nature and a simpler way of living may be inspired by current events, but its origins are in premodern medicine and spirituality.

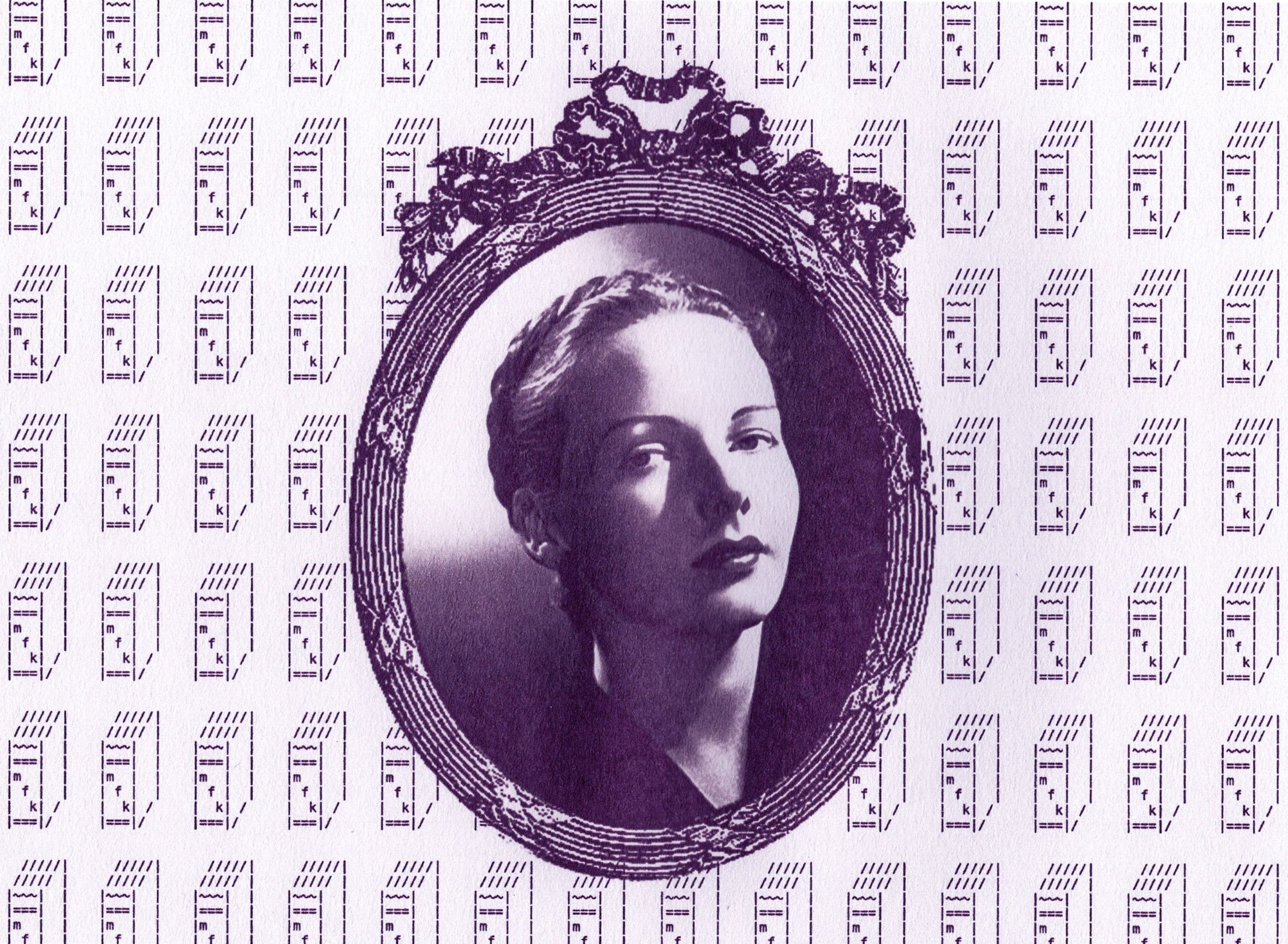

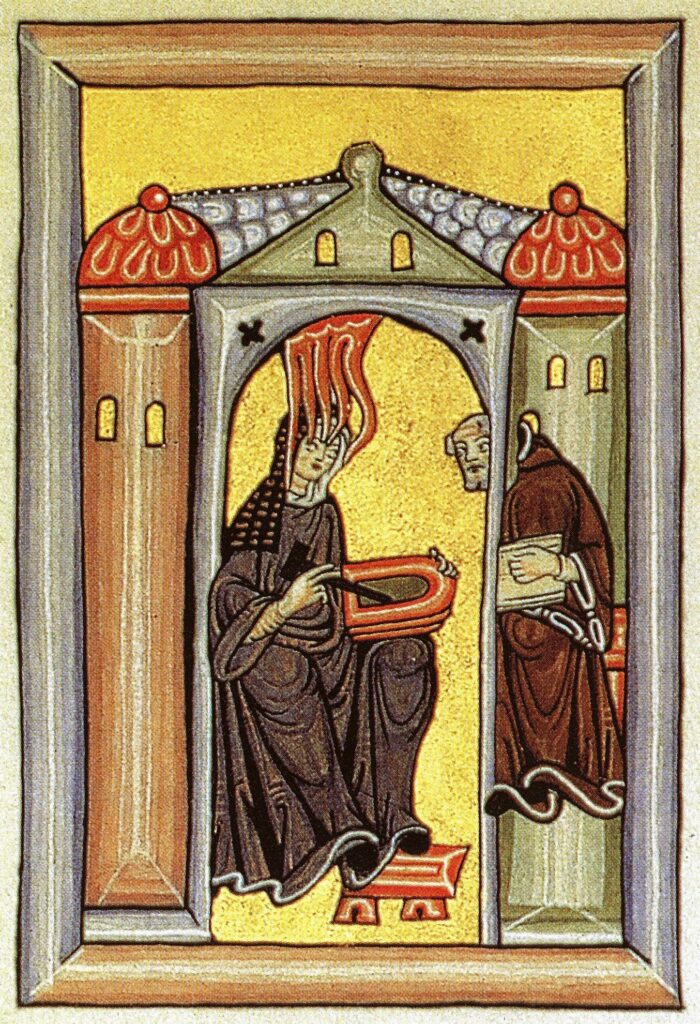

One pioneer of the healing power of nature takes us back to 12th century Germany, where Hildegard of Bingen, a Benedictine abbess, practised as a medical writer and practitioner (as well as a well-known composer, philosopher, mystic and visionary). Now considered to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany, Hildegard became familiar with plants and healing through working in the monastery’s herbal garden and infirmary. Bringing together these two ways of knowing, she experimented with combining physical treatment with holistic and spiritual healing. Over 800 years later, her botanical and medical writings have now been translated, recounted and published in a number of books hailing Hildegard von Bingen a groundbreaking contributor to Western medicine and healing

The Physic Garden and the Physical Body

Hildegard’s writings drew from her spiritual learnings and visions, which she experienced from early childhood. Praising her work in Hildegard of Bingen’s Medicine (1988), Drs. Wighard Strehlow and Gottfried Hertzka write:

“In this regard, she teaches us that we have an inner wisdom that is more sophisticated than profound outer study and experience. If we relied more on that today, we would undoubtedly have better healers.”

The words “listen to your body” echo the mantras of today’s self-care movement, which teaches us to pay attention to the signals our bodies and brains fire off when we are approaching burn-out or need to take better care of ourselves. Hildegard, although concerned with our relationship with the Divine (as a nun and eventual abbess), claimed that to heal ourselves we must connect to the world around us –– specifically nature. Not such a groundbreaking proposal now, given that the mental, physical and social benefits of nature are gaining more credibility and reliance in the face of climate and health crises.

Hildegard adopted the healing system of the Four Humors (which dates back as far as the ancient Greeks) is not dissimilar to Eastern practises such as Ayurveda, a traditional Indian medicine which names three bodily humors (doshas) that represent the nervous system, enzymes, and mucus. Hildegard’s first written work on natural healing, Physica, contains nine books describing the medicinal properties of different “natural tools” (which she refers to as naturalia): Plants, Elements, Trees, Stones, Fish, Birds, Animals, Reptiles and Metals. Ayurvedic medicines also often focus on combinations of herbs, minerals and metals; while a link between Hildegard’s medicine and Ayurveda is not known, Ayurvedic ideas date back to the first millennium BCE1.

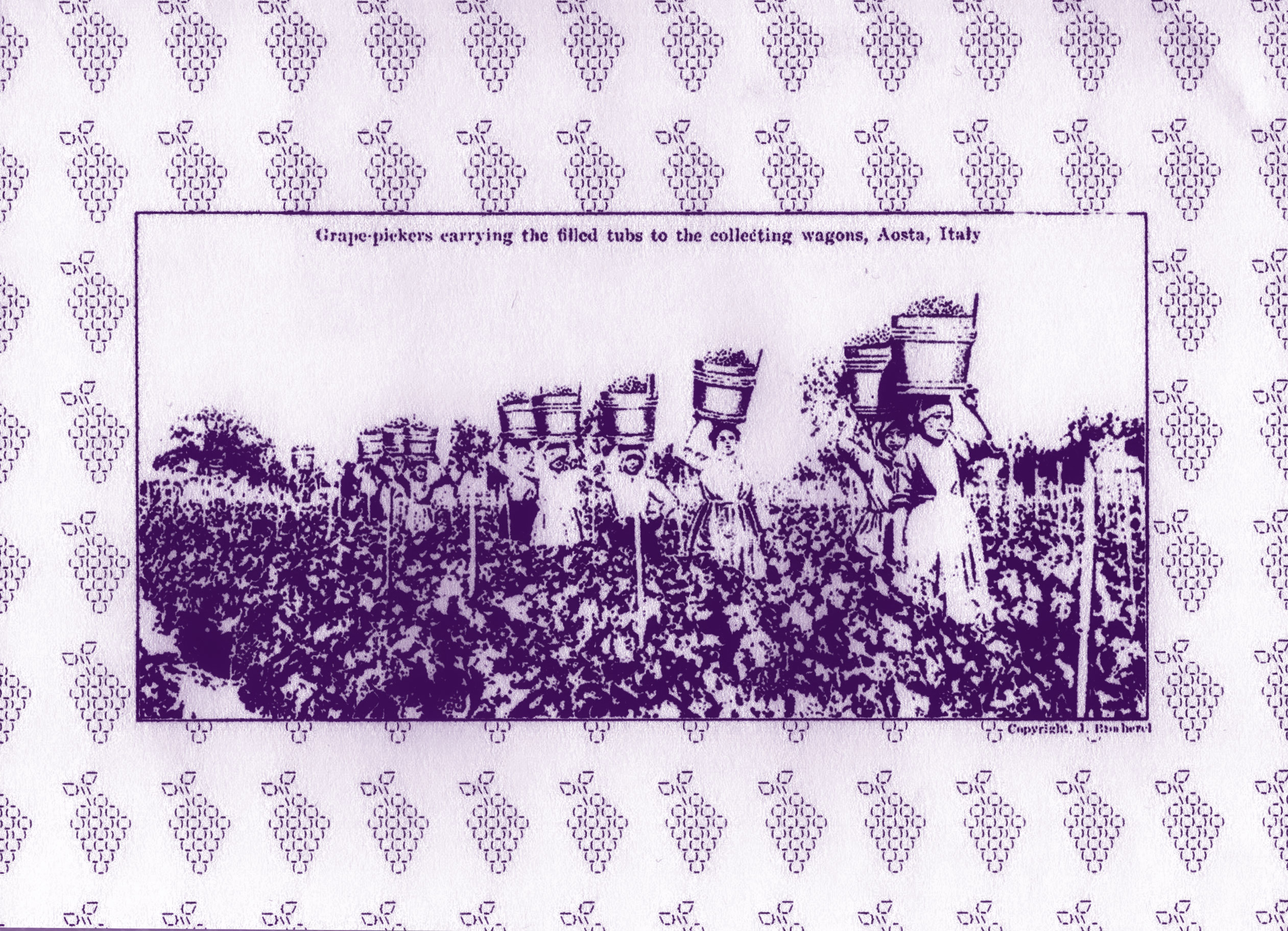

Her second work, Causae et Curae (or Causes and Cures), focuses on the human body and its connection to the rest of the natural world, detailing home remedies for common ailments –– likely discovered in the monastery’s physic garden which she then led. A physic garden, originally known as an “apothecary garden”, grew plants for purposes such as dyeing, healing and cooking for the residents of monasteries or mansions (Cowbridge Physic Garden). One such remedy was a so-called “flu powder” the primary ingredient of which was powdered geranium, which could be mixed into a spelt pancake, cooked into a warm glass of wine, or consumed with salt on bread (Hildegard of Bingen’s Medicine, 1988). Other remedies include a lungwort wine for respiratory issues. Lungwort, whose mottled leaves resemble diseased lungs, is a herb still commonly used by herbalists to ease breathing difficulties and treat coughs.

- 1. Dominik Wujastyk, The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings.

In fact, many of the ingredients used in Hildegard’s cures can be found in herbalist practises and popular remedies today, including fennel for digestion and ginger for the immune system. Dr. Victoria Sweet, a physician and historian who has studied Hildegard’s work, suggests that the Middle Ages are in fact “the invisible matrix, the microtubular structure, that underlies Western culture,” claiming that the houses we live in, the gardens we nurture, the food we eat and the way we eat it resemble the lifestyle of the Middle Ages.

Gardening as Medicine, Medicine as Gardening

Hildegard’s spiritual concept of Viriditas is a guiding principle throughout her works. Meaning “greenness”or “growth”, Viriditas represents the “greening power” thought to sustain human beings. Drawing parallels between humans and plants, Hildegard suggested that we too could grow and heal, like a garden, with the help of plants’ natural properties. The work that goes into nurturing this “greening power” is reflected in modern holistic medicine, the self-care movement, and the current back-to-the-land movement, which suggests we engage in healing as an act of gardening and gardening as an act of healing.

While many of Hildegard’s medical suggestions would be debunked today— for example, “It is nevertheless good and healthy to forego breakfast until before midday, or around noon, because it improves the digestion” or describing the human stomach as “somewhat wrinkled…so that it can retain the food for digestion and not let it slip away too quickly” — there is no doubt that Hildegardian medicine made a significant contribution to the way we value nature in the role of health and wellbeing (not to mention women’s place in medicine and theology).

In the 1970s, the expanding New Age movement increased interest in Hildegard’s work. Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation The Dinner Party features a place set for Hildegard of Bingen, among 38 other famous women throughout history. It is important to acknowledge how our contemporary movements err on commodification, with the push to make holistic medicine and a reconnection with nature more palatable for the majority. There is a lesson to be learned from Hildegard’s lifelong work that isn’t simply to consume more spelt bread and herb-infused wine, but to look to the resources provided to us by nature and look after them as we would wish to be looked after. In turn, the intuition to approach our own bodies as we would a garden, investing in the slow, communal act of tending to our own growth, suggests a return to Hildegard’s Viriditas, and a restoration of bodily trust in nature.