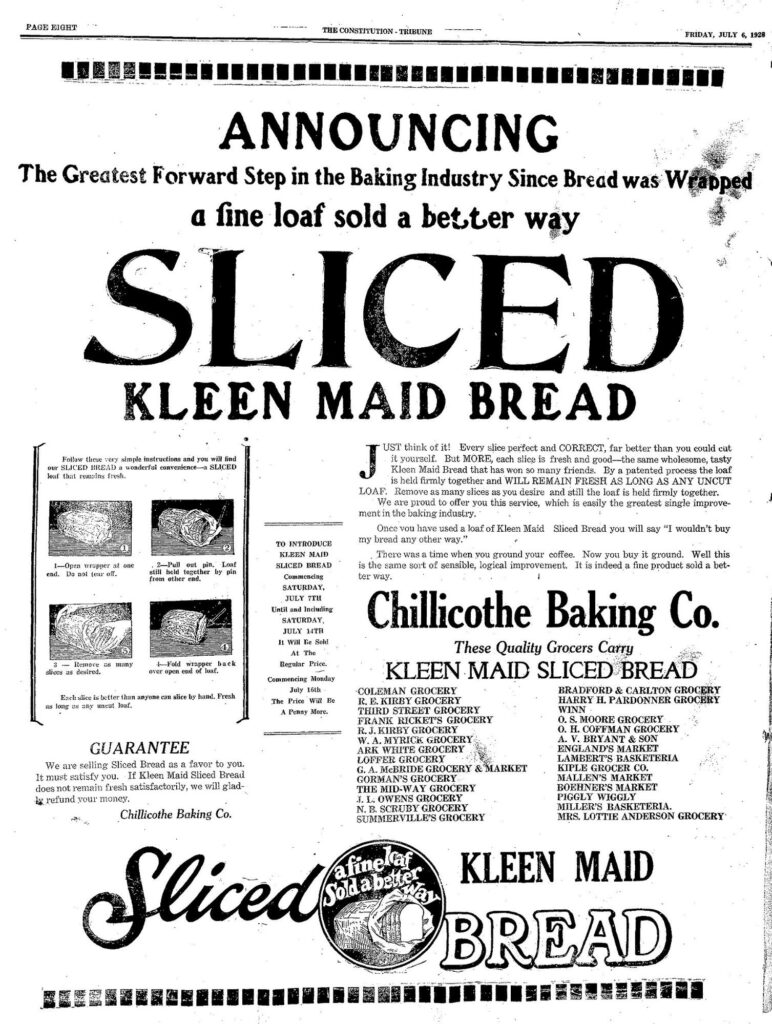

The first pre-sliced loaf of bread was sold on July 7th, 1928. Produced by Chillicothe Baking Company, Missouri, the bread was advertised as “The Greatest Forward Step in the Baking Industry Since Bread was Wrapped”. Using an automatic loaf-slicing machine developed by Otto Frederick Rohwedder, the invention paved the way for a new age of convenience within American food.

The advert below for Kleen Maid Bread illustrates the novelty and wonder of a bread that arrived ready to be toasted, spread or sandwiched by the consumer. A set of instructions explain how to unwrap and remove the slices: “1 – Open wrapper at one end. Do not tear off. 2 – Pull out pin. Loaf still held together by pin at other end. 3 – Remove as many slices as desired. 4 – Fold wrapper back over open end of loaf.” The marketing of sliced bread promoted ease, freshness and reliability, but also cleanliness.

“There was a time when you ground your coffee. Now you buy it ground. Well this is the same sort of sensible, logical improvement. It is indeed a fine product sold a better way.”

–– Chillicothe Baking Co.

CLEAN BREAD FOR PURE WOMEN

It wasn’t long before the popularity of pre-sliced bread spread nationwide, and by the 1930s brands such as Wonder Bread were selling their sliced loaves all over the US. Gone were the mornings of wrangling with loaf and bread knife to slice the family’s toast and sandwich bread. Now, perfectly formed, evenly-sliced bread was available to pick off a shelf, complete with metal pins to hold slices together, and preserve freshness.

There is no doubt that this marvel was targeted mainly at women. A promotional pamphlet published by Pacific Baking Co. in 1925 (pre-slicing invention) is titled “The Story of Kleen-Maid: The bread women have been looking forward to for 3800 years”. This bold claim is supported throughout by disparaging the historical methods of breadmaking (and the labour involved for consumption), proposing instead Kleen-Maid as a sanitary alternative for the American woman.The publication even refers to Biblical stories as “the earliest record of the beginning of the demand for clean bread”, hoping to appeal to the Christian beliefs of the American housewife.

Pacific Baking Co. goes on to boast that they “use no old fashioned or unclean methods” and welcome visits from those interested in “pure clean food”. Repeatedly (and one could argue, threateningly) inviting the public to “investigate conditions” of their bakeries to see the cleanliness for themselves, the publication resembles public health information more than a bread advertisement. Readers are reassured that not only are employees required to shower before beginning work, they are then provided with freshly laundered white suits—“notwithstanding the fact that the bakers themselves scarcely have occasion to come in personal contact with the bread”. Of course, as almost every step of the breadmaking process is now automated.

Each page of the booklet feels more and more dystopian as shaped to the American housewife interested in providing her family with healthy, clean food. Innovations in plumbing, water treatment and waste disposal in the decades prior had spurred a so-called Health Revolution, which resulted in a change in attitudes towards bathing and hygiene.1 As April D.J. Garwin writes, “advertisers began…to employ the fear of contagious diseases, as well as the virtue of beauty, to target consumers and to promote the sale of products”.

- 1. Garwin, April D.J., “Coming Clean: The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality.” Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2000.

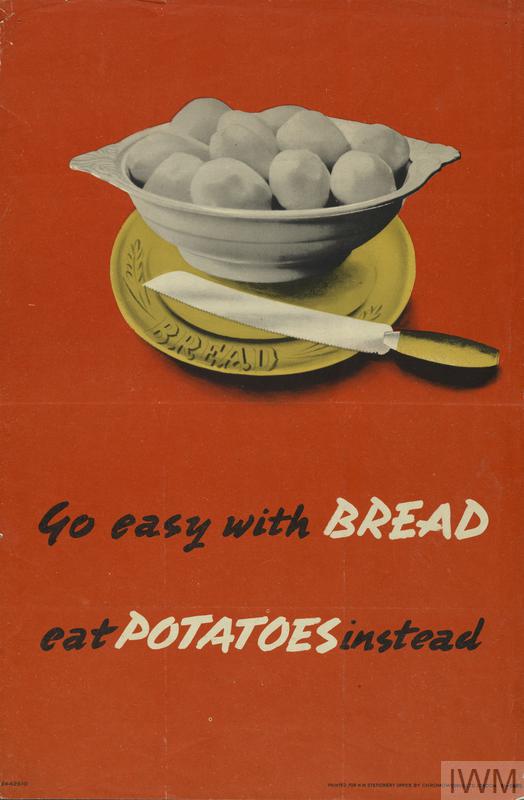

A SLICING SUSPENSION

By the 1940s, sliced bread had become a household staple, and the phrase, “greatest thing since sliced bread,” adapted from Chillicothe’s 1928 advertisement, had been coined. Rohwedder’s mechanical invention fostered a huge increase in bread consumption, which turned out to be a recipe for disaster during the Second World War. In January 1943, US officials imposed a ban on pre-sliced bread, so that costs and materials used for the packaging could instead go towards the war effort.

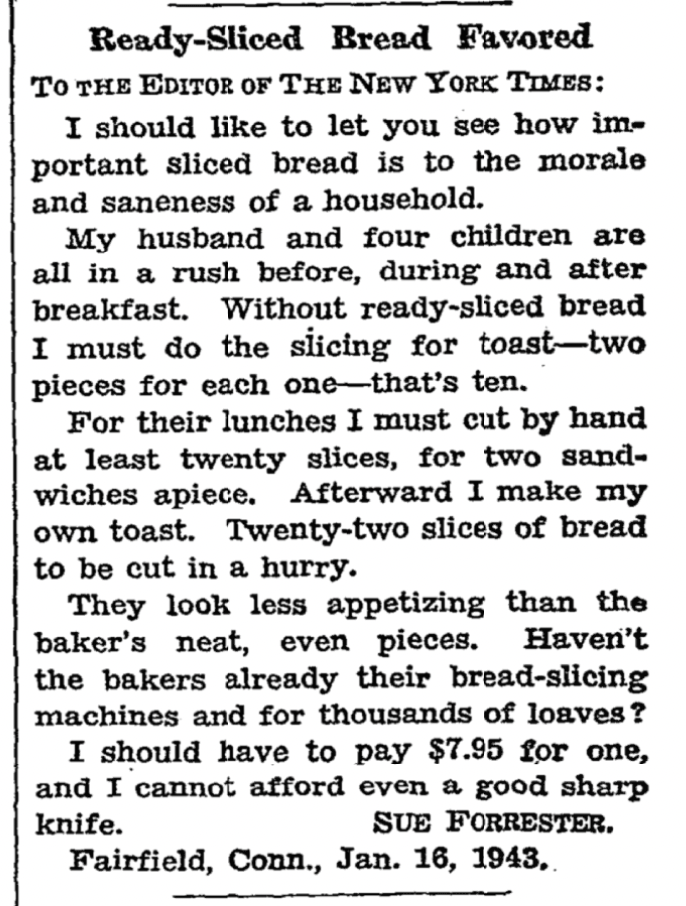

Just a few days after the ban was announced, a Sue Forrester wrote a letter to the Times expressing her frustration over the order. Beginning, “I should like to let you see how important sliced bread is to the morale and saneness of a household,” Forrester goes on to explain how she now must cut “at least twenty slices” for her husband and four children’s sandwiches, with another ten for their toast in the morning.2

- 2. Forrester, S,. “Ready-Sliced Bread Favored.” The New York Times, January 26, 1943.

Thankfully, the ban was short-lived due to its unpopularity, and pre-sliced loaves returned to the shelves that March. A newspaper article announcing the move reassured “housewives who have risked thumbs and tempers slicing bread at home for two months”. 3

- 3. The Associated Press, “Sliced Bread Put Back on Sale.” The New York Times, March 9, 1943.

TO BLEACH OR NOT TO BLEACH

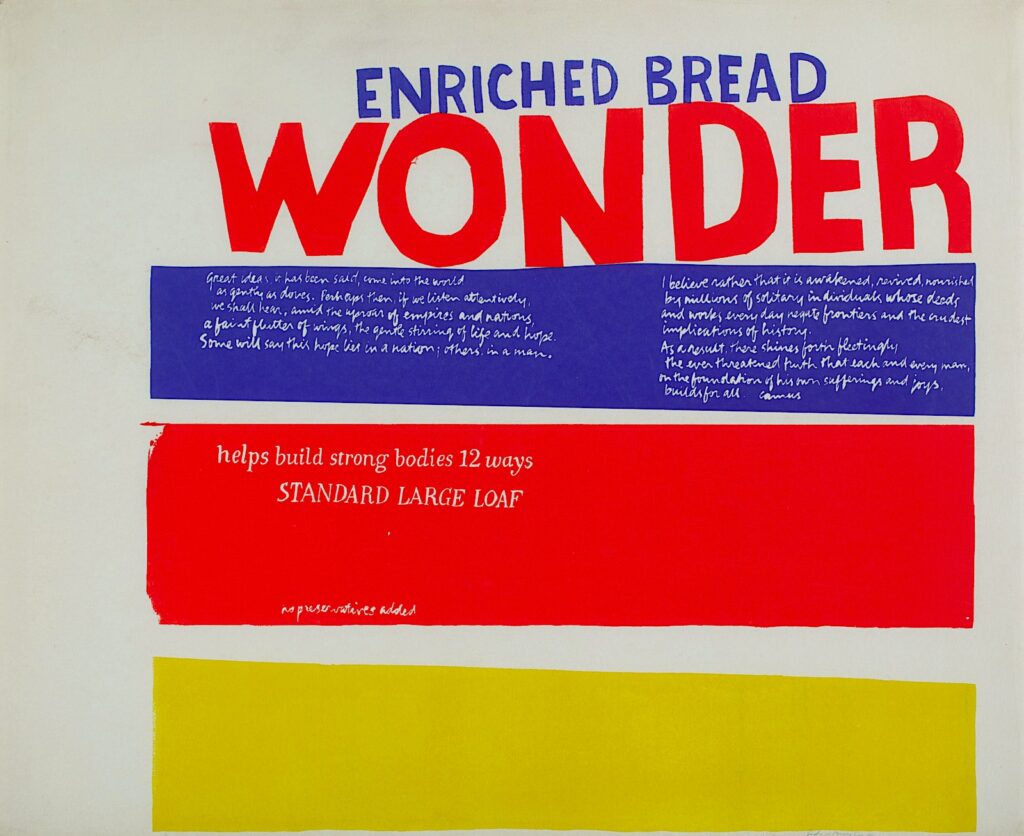

World War II was also the impetus for a government-sponsored initiative to “enrich” store-bought white bread with vitamins such as calcium, to prevent rickets in those joining the war effort.4 Wonder Bread developed the tag line “builds strong bodies 8 ways”, which then became “12 ways” as more nutrients were added to the flour — despite this only replacing those nutrients lost in the bleaching and processing of the flour.

- 4. “History of bread – 20th Century.” Federation of Bakers Ltd.

Perhaps this “enrichment” foreshadowed the downfall of the supermarket loaf. Although pre-sliced bread remained popular for its ease and convenience during the post-war years, in the following decades scientific knowledge has progressed, warning us of the dangers of processed food. This, coupled with consumers’ increasing interest in transparent supply chains and ingredients lists, welcomed the resurgence of the rustic, baker’s loaf.

Where once the pre-sliced, Kleen-Maid loaf symbolised a busy family interested in health and good food, now a freshly baked, wholegrain boule is a signifier of status, class and taste. We frown upon the plastic-wrapped, soft white squares and instead reach for the naked, flour-dusted nourishment of a cob, plait or baguette. As Aaron Bobrow-Strain writes in the opening of White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf, “supermarket white bread can pick up difficult bits of broken glass, clean typewriter keys, and absorb motor spills. Squeezed into a ball, it bounces on the counter.”5

A return to historical and artisanal methods has seen a rise in independent bakeries and a clientele that craves a bread that engenders a more distinctly human experience — the aroma of freshly baked loaves, the ritual of carrying sourdough home in brown paper, and the feeling of quiet pride at supporting a local store. Perhaps, in an age where we are so detached from what we eat and how it has got to our plate, slicing our own bread is the closest we can get to being a part of that process.

- 5. Bobrow-Strain, A. “White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf.” Beacon Press. 2012.

- 1. Garwin, April D.J., “Coming Clean: The Health Revolution of 1890-1920 and Its Impact on Infant Mortality.” Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2000.

- 2. Forrester, S,. “Ready-Sliced Bread Favored.” The New York Times, January 26, 1943.

- 3. The Associated Press, “Sliced Bread Put Back on Sale.” The New York Times, March 9, 1943.

- 4. “History of bread – 20th Century.” Federation of Bakers Ltd.

- 5. Bobrow-Strain, A. “White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf.” Beacon Press. 2012.