Major League Eating, the New York-based organization that oversees international professional eating contests, holds around 70 events each year, offering “dramatic audience entertainment”. Their online record table publishes the latest records held for over 200 food items, including matzo balls, peas, butter, cow brains and “spray cheese in a can”.

Although MLE was rather recently established in 1997, the concept of competitive eating is far from contemporary. Early motion picture footage by Thomas Edison’s production company depicts a pie-eating contest between two contestants, their hands tied behind their backs as they dive face-first again and again into their huckleberry pies.

So what has kept the appetite for eating contests alive? From the 19th century to the present day, crowds have gathered to watch hungry contestants compete against each other, the clock and their own digestive systems to be crowned winner.

FAT MEN: A TALE OF WHITE MALE PRIVILEGE

According to Sarah Lohman writing for Lapham’s Quarterly, the first recorded pie-eating contest took place in Toronto in 1878 as a charity fundraising event, and was won by an Albert Piddington –– whose prize was “a handsomely bound book”1. The New York Times reported on the event on January 22nd 1878, quoting Toronto’s Leader:

“The delicacy consisted of luscious very sticky raspberry tarts, placed on stools reaching up to the mouths of the competitors, who made the assault on their knees…A handsomely bound book was the prize which fell to the young gourmand’s lot. His deftness, cleanliness and quickness on the swallow excited great admiration –– his face being nearly as clean as when he went on the stage of the Grand Opera-house.”2

- 1. S. Lohman, 2016. “Pie Fight: A brief history of competitive eating”, Lapham’s Quarterly.

- 2. “Pie-Eating for a Prize”, The New York Times, January 22 1878, p.5.

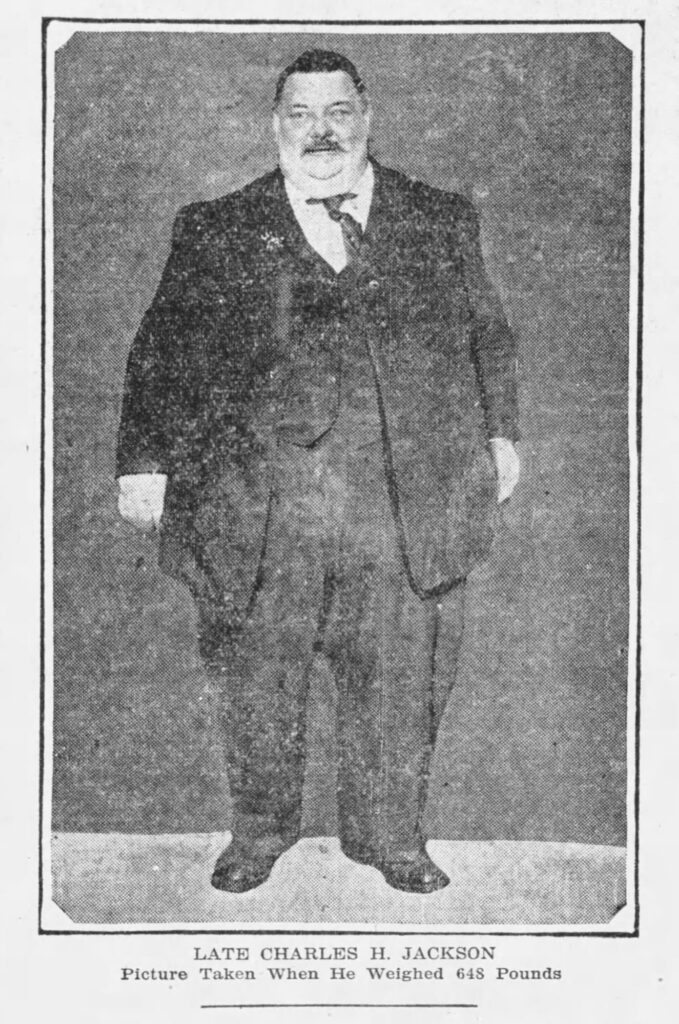

This sensory, almost romantic description of the tournament illustrates the wonder and excitement that spectators shared, as they gathered to witness other seemingly normal humans execute feats that appeared to defy bodily science. The admiration and respect shown to those with the ability to eat large quantities was mirrored in the establishment of Fat Men’s Clubs in the late 19th century. Resembling British gentlemen’s clubs, fat men’s clubs had strict criteria that members must weigh at least 200lbs. Most clubs also held eating contests to increase their chances of achieving a higher number on the scale at meetings.3 At a time when corpulence was often associated with wealth, success and good humor, meeting the requirements of a fat men’s club was a signifier that one was making money and living comfortably — and therefore, a powerful man.

- 3. A. Johnson, 2016. “The Art of Competitive Eating”, Gastronomica, 16(3), pp.111-114.

An account of the New England fat men’s club outing in the Boston Globe in 1910 quotes the father of the club, David Wilkie:

“The time is coming when fat men will be in great demand for all positions of responsibility, particularly as honest bank cashiers.”4

This historic correlation between excessive eating and power helps to explain the development of competitive eating as a sport –– and in many cases, a career, particularly for men (fat women were of course still openly mocked or deemed unattractive).

However, the Great Depression led to a decrease in personal income for most, and with it came weight loss. A 1931 New York Times segment puts out an urgent call for new members to apply to the United States Fat Men’s Club due to the Depression reducing “the tonnage of its membership by 3,650 pounds, leaving the gross avoirdupois of the 1,472 members at the alarmingly low total of 332,672 pounds.”5 This data still puts the average member at a weight of 226lbs, heavier than most top-ranked MLE eaters today.

The clubs began to disband from the 1920s and ’30s, as new public health advice warned of the risks of obesity.6 Weighing oneself became less of a public celebration and more of a private proceeding, soon making fat men’s clubs obsolete.

- 4. “Fat Men Have Outing and Banquet”, The Boston Globe, September 6 1910, p.2.

- 5. “Trade Slump Lowers Tonnage of National Fat Men’s Club”, The New York Times, January 21 1931, p.20.

- 6. T. Basu, 2016. “The Forgotten History of Fat Men’s Clubs”, NPR.

AN AMERICAN TRADITION

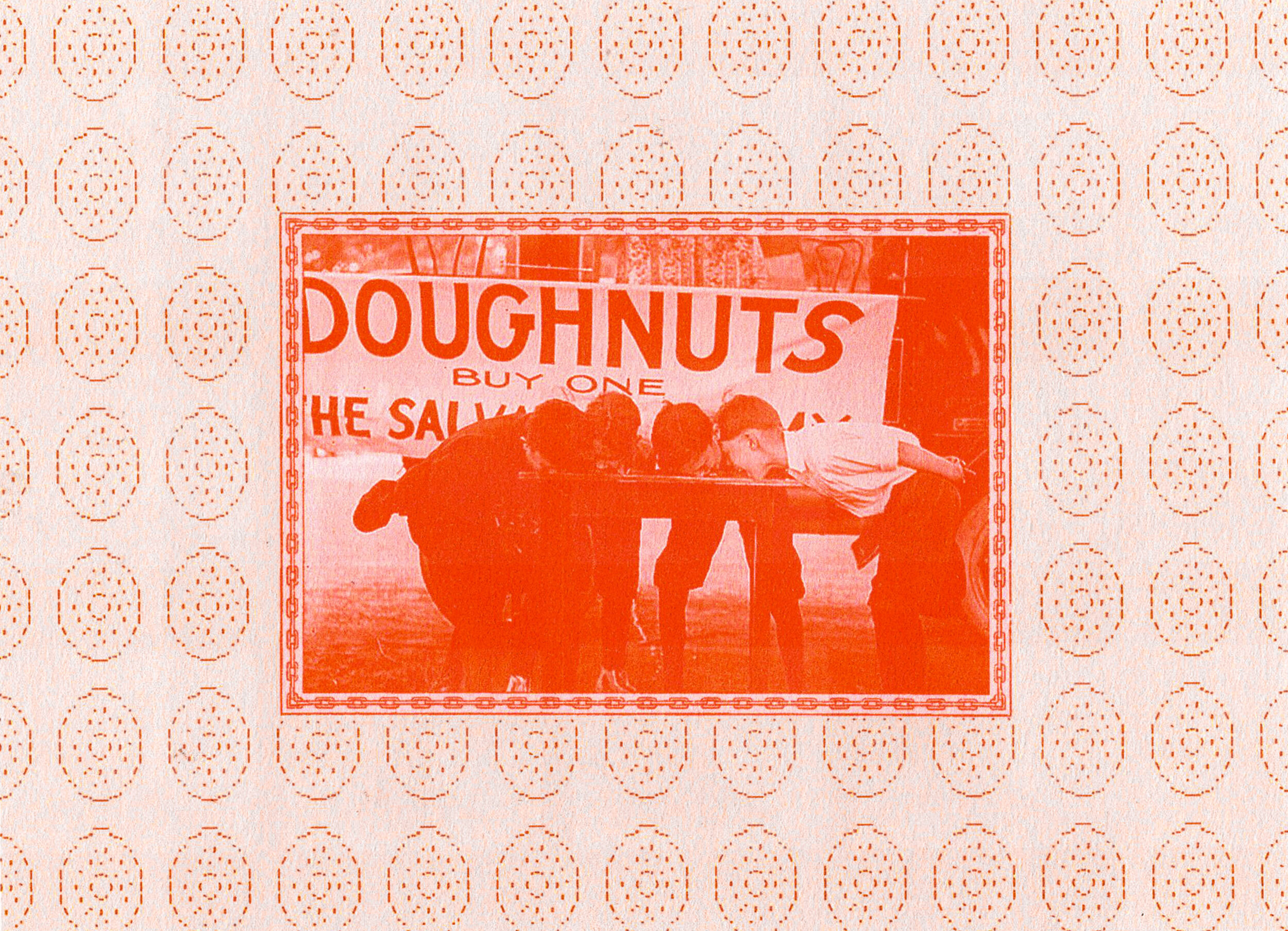

Despite this, the curiosity and excitement of watching others eat unimaginable quantities of food has persisted, with eating contests continuing throughout the 20th century in the form of fraternal bonding exercises, neighborhood community events or professional competitions.

Possibly the most renowned eating contest is Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest, which has taken place every year since 1916. Now governed by Major League Eating, it is described as “an American holiday tradition”. The 2022 results name Joey Chestnut as winner of the men’s championship after eating 63 hot dogs in 10 minutes, and Miki Sudo winning the women’s with 40 hot dogs. An account of the 1972 event in the New York Times recalls:

“Nearby, at Nathan’s Famous, Jason Schechter, a Brooklyn College student, won the annual hot dog‐eating contest by devouring 14 franks in three and a half minutes. His prize was a book of certificates for 40 more hot dogs.”7

The grand prize of this year’s contest was $40,000 –– but MLE also notes that a regular feature of the event is the hot dog brand’s annual donation of 100,000 hot dogs to the Food Bank for New York City. This absurd juxtaposition of overeating for prize money, with a donation of food to the city’s food bank, feels like an uncomfortable quandary of our consumer culture. While over 1 million New York City residents are food insecure, spectators gather to witness the entertainment of what is really a colossal waste of food for prize money. Couldn’t this money be better spent going directly to those who need it?

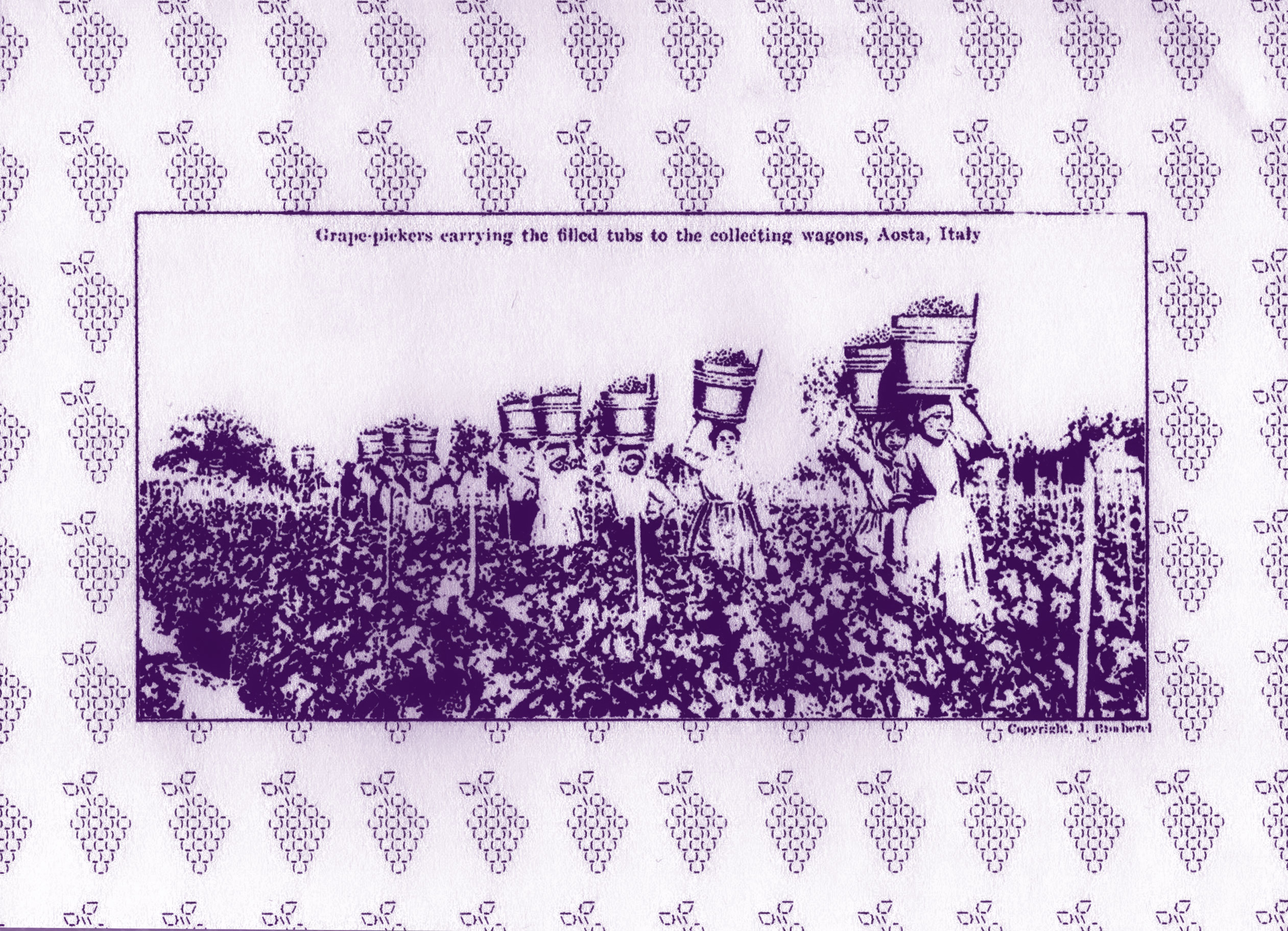

Many competitions now seem to be sponsored by food brands, such as SPAM, TurDucken or Armour, with prizes that total thousands of dollars –– meaning record-holding eaters can make their living through competing. Gone is the poetic wonder of Albert Piddington’s 1878 victory over raspberry tarts, and the silent comedy of Edison’s short Pie Eating Contest film

These attitudes feel reminiscent of the 1973 film La Grande Bouffe (dir. Marco Ferreri), which tells the tale of four friends who gather in a mansion for the weekend with the intent of eating themselves to death. The surreal narrative satirizes consumerism and the upper-middle class, forcing the characters to be killed off, one by one, by their decadent tastes. Our insatiable need to be constantly consuming, never reaching satisfaction, is not a new phenomenon –– think of the history of Roman banquets, hedonistic gatherings of luxurious food and extravagant entertainment. There is a reason that when an eater vomits during a contest, it is known as a “Roman incident.”

In The Art of Competitive Eating (2016), Adrienne Rose Johnson writes of her quest to understand competitive eating. After speaking to various eaters in 2008 to understand their motivations behind competing, and attending the famed hot dog eating contest on Coney Island, Johnson concludes, “in the moments of an eating contest, it all becomes new again…astonished by the bodies we live in and the world in which we find ourselves.” The innocent wonder she describes as a spectator in amongst that 10 minute countdown, confirms that perhaps the draw of competitive eating is simply the belonging felt by all being united by one shared interest, one reason for being: to eat.

- 1. S. Lohman, 2016. “Pie Fight: A brief history of competitive eating”, Lapham’s Quarterly.

- 2. “Pie-Eating for a Prize”, The New York Times, January 22 1878, p.5.

- 3. A. Johnson, 2016. “The Art of Competitive Eating”, Gastronomica, 16(3), pp.111-114.

- 4. “Fat Men Have Outing and Banquet”, The Boston Globe, September 6 1910, p.2.

- 5. “Trade Slump Lowers Tonnage of National Fat Men’s Club”, The New York Times, January 21 1931, p.20.

- 6. T. Basu, 2016. “The Forgotten History of Fat Men’s Clubs”, NPR.